The Structure and the Resources of Entrepreneurial Network - Esential Factors to Survival and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traffickers of Human Beings in Romania

MERCHANTS OF LIVING SOULS: TRAFFICKERS OF HUMAN BEINGS IN ROMANIA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE STANFORD PROGRAM IN INTERNATIONAL LEGAL STUDIES AT THE STANFORD LAW SCHOOL, STANFORD UNIVERSITY, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF THE SCIENCE OF LAW BY FLORIN VLAD © MAY 2006 ABSTRACT This paper highlights the importance of empirical methods to delineate the profile of the traffickers in Romania, and the need to understand the factors that influence the behavior of traffickers. Studying and responding to trafficking in human beings has been flawed by the vagueness or inaccuracy of the research tools deployed, making it difficult to satisfy the normative component of the political objectives of legal regulation to criminalize trafficking activities. The trafficking of human being needs a research approach more focused on all the key actors, and more rigorous in methodology. Due to the criminal “hidden” nature of the trafficking operations and the scarcity of empirical data, both qualitative and qualitative analyses have been deployed. I conclude that traffickers are increasingly mobile, adaptable in terms of trafficking schemes and routes, are well connected to the environment from which the victims are recruited. Recently Romanian legislation is combating trafficking against a backdrop of increasing demand for trafficked victims, as well as social norms that favor irregular migration. Budgetary restraints and a lack of institutional coordination hamper the efforts of the government to more efficiently prosecute -

What Happened to Collective Bargaining During the Great Recession?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Visser, Jelle Article What happened to collective bargaining during the great recession? IZA Journal of Labor Policy Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Visser, Jelle (2016) : What happened to collective bargaining during the great recession?, IZA Journal of Labor Policy, ISSN 2193-9004, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 5, Iss. 9, pp. 1-35, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40173-016-0061-1 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/154731 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.econstor.eu Visser IZA Journal of Labor Policy (2016) 5:9 DOI 10.1186/s40173-016-0061-1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access What happened to collective bargaining during the great recession? Jelle Visser1,2 Correspondence: [email protected] 1Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Abstract Labour Studies (AIAS), P.O. -

No 2016/2006 of 19 December 2006 Adapting Several Regulations

L 384/38EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.12.2006 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 2016/2006 of 19 December 2006 adapting several regulations concerning the common organisation of the market in wine by reason of the accession of Bulgaria and Romania to the European Union THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (6) Article 8(2) of Commission Regulation (EC) No 884/2001 of 24 April 2001 laying down detailed rules of application concerning the documents accompanying the carriage of wine products and the records to be kept Having regard to the Treaty of Accession of Bulgaria and in the wine sector (4) contains entries in all the languages Romania, and in particular Article 4(3) thereof, of the Member States. That provision should include the entries in Bulgarian and Romanian. Having regard to the Act of Accession of Bulgaria and Romania, and in particular Article 56 thereof, (7) Article 16(1) of Commission Regulation (EC) No 753/2002 of 29 April 2002 laying down certain rules for applying Council Regulation (EC) No 1493/1999 as regards the description, designation, presentation and Whereas: protection of certain wine sector products (5) contains certain entries in all the languages of the Member States. That provision should include the entries in Bulgarian and Romanian. (1) Certain technical amendments are necessary in several Commission Regulations concerning the common orga- nisation of the market in wine in order to carry out the (8) Annex VIII to Regulation (EC) No 753/2002 contains a necessary adaptations by reason of the accession of reference to Bulgaria and Romania as thirds countries. -

Academic Research in Romania - Critical Issues and New Challenges

Academic Research in Romania - Critical Issues and New Challenges 1. Introduction It is now widely recognized that research is one of the key factors required for achieving the objective of turning the EU into a competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy. Research and development involve 3 main types of institutional actors: universities, public research organizations and enterprises (the concept of academic research used in this paper refers to research carried out in universities). In the context of the Lisbon (2000) and Barcelona (2002) goals, the future of the Europe’s university research has become a key subject not only for policy makers but also for academic leaders, researchers , experts, as well as for the civil society. In particular, there is a strong requirement for Europe’s universities to become more competitive in their research and to improve their interactions with the industry and the local society. The enlargement of the EU with 12 members has increased the R&D capacity of the EU on the one hand but it has accentuated the discrepancies within the community on the other. The purpose of the present paper is to highlight some of the critical issues of the academic research in Romania, in the context of the new challenges facing universities world wide. 2. European Concerns with regard to the Europe’s University Research In the EU, universities are the main producer of scientific knowledge, they employ about 36% of researchers (compared to 14% in the US and 25% in Japan), they provide 20% of European research and the majority of fundamental research (80%).1 Over the last years, European documents point out that the average quality of European University activities, mainly research, is good but not excellent.2 International comparisons are not favorable to European Universities. -

European Wilderness Journal

European Wilderness Journal European WILDERNESS SOCIETY WWW.WILDERNESS-SOCIETY.ORG No. 1/2014 JOIN AND BE PART OF IT € 7,50 Donation Fee European Wilderness Journal The future of wilderness in Europe Dear Friends of the wild! Letter to the Editors the past 15 years a lot has been achieved for Europe’s wilderness. These In achievements by various organisations were partially acknowledged by Wilderness is nowhere as important as it is in Europe, the the 10th World Wilderness Congress, the WILD10 in Salamanca, Spain. world’s most densely populated continent. The good news is that, in the last 20 years, great and critical strides have oc- Our vision curred to help raise awareness of and protect wild nature…but Since we need to go further for future generations! The launch of the new this work has really only just begun. The European Wilderness Vision for a Wilder Europe inspired us to set up the European Wilderness Society is the force needed to continue and build this momen- Society, which is a new entity that strives for more and better protection of tum. We all need to join, assist, and promote this important wilderness in Europe. initiative. Vance G Martin, Our objectives President: The WILD Foundation, World Wilderness Congress • Identifying and assisting in the management and lobbying for existing wilderness areas in Europe • Increase the total designated wilderness area in order to balance our hu- The newborn EWS does a great job. Your homepage is man footprint on the continent very attractive and well-made. Congratulations. • Inspire Europeans to care for our wild places across the continent Bernhard Kohler WWF Austria Our mission As its name implies, the new entity focuses its efforts on wilderness, on Europe and on joint actions involving the public. -

IFRC-Central Europe Annual Appeal 2005 (Appeal No.05AA066

CENTRAL EUROPE 3 May 2006 In Brief Appeal No. 05AA066; Annual Report; Period covered: January - December 2005 Appeal target: CHF 1,999,357 (USD 996,890 or EUR 781,845); Appeal coverage: 111 % (Please click here to go directly to the attached Financial Report). Related Emergency or Annual Appeals: Central Europe Annual Appeal 2005. For details please see the website at http://www.ifrc.org/cgi/pdf_appeals.pl?annual05/05AA066.pdf Central Europe Annual Appeal 2005 – Programme Update no.1. For details ple ase see the website at http://www.ifrc.org/cgi/pdf_appeals.pl?annual05/05AA06601.pdf Central Europe Annual Appeal 2005 – Programme Update no.2. For details please see the website at http://www.ifrc.org/cgi/pdf_appeals.pl?annual05/05AA06602.pdf Annual Appeals 2005 for Europe and Central Asia region. For details please see the website at http://www.ifrc.org/where/europe.asp Central Europe Annual Appeal 2006-2007. For details please see the website at http://www.ifrc.org/cgi/pdf_appeals.pl?annual06/MAA66001.pdf Romania: Floods emergency appeal issued in April 2005, and minor emergency appeal issued in July 2005; Bulgaria: Floods minor emergency appeals issued in June and August 2005; Bosnia & Herzegovina minor emergency appeal issued July and December 2005; Serbia and Montenegro emergency appeal issued in April 2005, Annual Appeals for Serbia and Montenegro including Kosovo, and Bosnia and Herzegovina For further information please contact: · Caroline Mawdsley, Acting head of office, RD Budapest, Phone: +36 1 248 3324, fax 36 1 248 3322, email: [email protected] · Sune Follin, Acting Head of Regional Delegation, Phone: +387 33 666 009, email: [email protected] · Erja Reinikainen, Regional Officer, Europe Department, Secretariat Geneva, Phone: +41 22 730 43 19, email: [email protected]. -

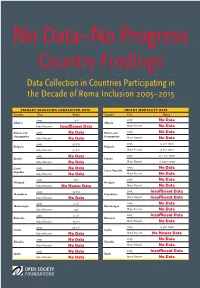

No-Data-No-Progress-Country-Reports

No Data–No Progress Country Findings Data Collection in Countries Participating in the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005–2015 PRIMARY EDUCATION COMPLETION RATE INFANT MORTALITY RATE Country Year Roma Country Year Roma 2005 14% 2005 No Data Albania Albania Most Recent Insuffi cient Data Most Recent No Data Bosnia and 2005 No Data Bosnia and 2005 No Data Herzegovina Herzegovina Most Recent No Data Most Recent No Data 2005 28.3% 2005 25 per 1000 Bulgaria Bulgaria Most Recent 31.6% Most Recent 25 per 1000 2005 No Data 2005 25.1 per 1000 Croatia Croatia Most Recent No Data Most Recent 11.5 per 1000 Czech 2005 No Data 2005 No Data Czech Republic Republic Most Recent No Data Most Recent No Data 2005 76% 2005 No Data Hungary Hungary Most Recent No Newer Data Most Recent No Data 2005 50.8% 2005 Insuffi cient Data Macedonia Macedonia Most Recent No Data Most Recent Insuffi cient Data 2005 9.2% 2005 No Data Montenegro Montenegro Most Recent 20% Most Recent No Data 2005 31.7% 2005 Insuffi cient Data Romania Romania Most Recent 19.7% Most Recent No Data 2005 22.7% 2005 25 per 1000 Serbia Serbia Most Recent No Data Most Recent No Newer Data 2005 No Data 2005 No Data Slovakia Slovakia Most Recent No Data Most Recent No Data 2005 No Data 2005 Insuffi cient Data Spain Spain Most Recent No Data Most Recent No Data No Data—No Progress Country Findings No Data—No Progress Country Findings Data Collection in Countries Participating in the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005–2015 August 2010 Roma Initiatives Copyright © 2010 by the Open Society Foundations. -

RJEA OCTOBER 2005 Ptr Pdf

Romanian Journal of European Affairs Vol. 5, No. 3, October 2005 - Special Issue EUROPEAN INSTITUTE OF ROMANIA Director Nicolae Idu Editor-in-Chief Oana Mocanu Associate Editors Ioana Mureºan Irina Râmniceanu Gilda Truicã Editorial Board Farhad Analoui - Professor in International Development and Human Resource Management, the Center for International Development, University of Bradford, UK Daniel Dãianu - Professor, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest, former Minister of Finance Eugen Dijmãrescu - Vice Governor of the National Bank of Romania Nicolae Idu - Director General of the European Institute of Romania Andras Inotai - Professor, Director of the Institute for World Economics, Budapest Mugur Isãrescu - Governor of the National Bank of Romania Alan Mayhew - Jean Monnet Professor, Sussex European Institute Costea Munteanu - Professor, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest Jacques Pelkmans - Jan Tinbergen Chair, Director of the Department of European Economic Studies, College of Europe - Bruges Andrei Pleºu - Rector of New Europe College, Bucharest, former Minister of Foreign Affairs, former Minister of Culture Cristian Popa - Vice Governor of the National Bank of Romania Tudorel Postolache - Member of the Romanian Academy, Ambassador of Romania to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg Helen Wallace - Professor, Director of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, Florence CONTENTS FOREWORD . ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIVE-YEAR ANNIVERSARY.... 5 Nicolae Idu . NEW AND FUTURE MEMBER STATES: ROMANIA'S ROLE IN THE EU-27 9 Mugur Isãrescu . NEW AND FUTURE MEMBER STATES - WHAT COULD BE THEIR ASSUMED ROLE . IN A 27-MEMBER EUROPEAN UNION? 13 Mihai-Rãzvan Ungureanu . THE ACCESSION BETWEEN CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES 17 Mircea Geoanã . THE EUROPEAN CONSTRUCTION - RECENT CHALLENGES 19 Ene Dinga . -

FDI in Romania Between EU and the Global Economic Crisis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Economics and Finance 23 ( 2015 ) 644 – 651 2nd GLOBAL CONFERENCE on BUSINESS, ECONOMICS, MANAGEMENT and TOURISM, 30-31 October 2014, Prague, Czech Republic FDI in Romania between EU and The Global Economic Crisis Iloiu Mirelaa*, Csiminga Dianaa, Mangu Sorina aUniversyt of Petrosani, University Street no.20, 332006, Petrosani, Romania Abstract In the context of globalization, foreign direct investment represent the main way of participation in international economic exchanges for Romania. The presence of FDI in Romania is a tradition since the early twentieth century, but they had a limited application in the postwar period and until 1989. The liberalization of the legal framework after 1989 led to the expansion of FDI in all fields of activity with beneficial effects on the national economy. Given the considerable negative impact of the economic crisis on FDI inflows in Romania, this paper aims to analyze the evolution of FDI in Romania after 1989 with special reference to two issues: adhering to the EU and the global economic crisis. The conclusions of this analysis can be used as general guidelines to reconsider the policies and instruments to attract FDI in Romania in the post crisis. ©© 20152014 The The Authors. Authors. Published Published by by Elsevier Elsevier B.V. B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (Selectionhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ and/ peer-review under responsibility of). -

Tax Policy Under the Curse of Low Revenues: the Case of 10

TAX POLICY UNDER THE CURSE OF LOW REVENUES: THE CASE OF 10. ROMANIA (PART I)12 Daniel DAIANU3 Ella KÁLLAI4 Laurian LUNGU5 Abstract The Romanian tax revenue-to-GDP ratio has been far below the average level of both the European Union and the New Member States for many years. The decade long growth cycle hid significant structural imbalances in the public budget. This paper attempts to identify reasons why tax revenues in Romania are the lowest among the EU-27 countries. It takes a broader perspective by looking at the main sources of tax revenues over the last two decades. Implications of the policy regime change following the introduction of flat tax in 2005 are considered. It also does a few comparisons with other countries from Central and Eastern Europe by looking at the main tax revenue components. Keywords: Budgetary Revenues, Taxation, Implicit Tax Rates, Arrears, Shadow Economy JEL Classification: H24, H25, H26, H30 Introduction Romania has registered persistently low budget revenues over the years. The Romanian tax revenue-to-GDP ratio has been far below the average level of both the 1 We thank Dan Armeanu, Nicolae Chidesciuc, Giacomo Corneo, Margit Schratzenstaller- Altzinger, Dieter Vesper and Radu Vranceanu for their comments on an earlier draft. We also thank the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung for the financial support in undertaking this analysis. It goes without saying that we bear sole responsibility for its content. 2 Short version. This is a downsized version of the full study, which can be read in extenso on the site of the Romanian office of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung". -

The London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science New Eurostars? The labour market incorporation of East European professionals in London Krisztina Csedo Thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2009 UMI Number: U613420 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613420 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 THCSG f- lon n't 5431 Declaration 2 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. -

First European Quality of Life Survey

First European Quality of Life Survey: Quality of life in Bulgaria and Romania Authors: Ioan MÆrginean (coordinator), Iuliana Precupe¶u, Vassil Tzanov, Ana Maria Preoteasa and Bogdan Voicu with Iskra Beleva (contributor) Research institute: Research Institute for Quality of Life, Romanian Academy, Bucharest Research managers: Branislav Mikulic and Hubert Krieger Research project: Quality of life in Europe First European Quality of Life Survey: Quality of life in Bulgaria and Romania Wyattville Road, Loughlinstown, Dublin 18, Ireland - Tel: (+353 1) 204 31 00 - Fax: (+353 1) 282 42 09 / 282 64 56 email: [email protected] - website: www.eurofound.europa.eu Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2006 ISBN 92-897-0959-6 © European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2006 For rights of translation or reproduction, applications should be made to the Director, European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Wyattville Road, Loughlinstown, Dublin 18, Ireland. The European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions is an autonomous body of the European Union, created to assist in the formulation of future policy on social and work-related matters. Further information can be found on the Foundation website at www.eurofound.europa.eu European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions Wyattville Road Loughlinstown Dublin 18 Ireland Telephone: (+353 1) 204 31 00 Fax: (+353 1) 282 42 09 / 282 64 56 E-mail: [email protected] www.eurofound.europa.eu Printed in Denmark The paper used in this publication is chlorine-free and comes from managed forests in Northern Europe.