The Commodification of Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pop Stars RE ORDER 17/10/02 3:05 PM Page 2

Pop Stars RE ORDER 17/10/02 3:05 PM Page 2 Pop Stars Series EZP-07 EZP-10 Duets Vol 1 Hits Of Kylie Vol 1 1) You’re The One That I Want Grease 1) Can’t Get You Outta My Head 2) I Got You Babe Chrissie Hinde & UB40 2) Spinning Around 3) Pure & Simple Hear’ say 3) On A Night Like This 4) Up Where We Belong Joe Cocker & Jennifer Warnes 4) The Loco-motion 5) I’ll Be Missing You Puff Daddy & Faith Evans 5) I Should Be So Lucky 6) Endless Love Lionel Richie & Diana Ross 6) Fever 7) Don’t Go Breaking My Heart Elton John & Kiki Dee 7) Kids (duet with Robbie Williams) 8) I Know Him So Well Elaine Paige & Barbara Dickson 8) Got To Be Certain DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES EZP-08 EZP-11 Hits Of Steps Hits Of westlife 1) Tragedy 1) Flying Without Wings 2) Summer Of Love 2) I Have A Dream 3) Say You’ll Be Mine 3) If I Let You Go 4) One For Sorrow 4) Queen Of My Heart 5) Love’s Got A Hold On My Heart 5) Swear It Again 6) Deeper Shade Of Blue 6) Uptown Girl 7) Better Best Forgotten 7) What Makes A Man 8) After The Love Has Gone 8) When You’re Looking Like That DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES EZP-09 EZP-12 Rock & Roll Xmas Hits Of S Club The No1 Christmas Seller 1) Merry Christmas Everybody Slade 1) You 2) I Wish It Could Be Christmas Wizzard 2) Bring It All Back 3) Last Christmas Wham 3) Have You Ever 4) Wombling Merry Christmas The Wombles 4) Don't Stop Movin' 5) A Spaceman Came Travelling Chris De Burgh 5) S Club Party 6) When A Child Is Born Johnny Mathis 6) You're My Number One 7) Merry Christmas Everyone Shakin Stevens 7) Two In A Million 8) Do They Know Its Christmas Band Aid 8) Never Had A Dream Come True 9) (New Year Countdown) Auld Lang Syne 9) Natural 10)Reach DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES www.easykaraoke.com ©. -

Placebo Greatest Hits Zip

Placebo greatest hits zip click here to download Placebo - Greatest Hits () [2CD] [ Kbps] [MEGA]. Disco 1. For What It's Worth Meds Every You Every Me Battle For The Sun Because I Want You. Download www.doorway.ru Direct Link Download. Download www.doorway.ru Mediafire Download. Free download info for the Indie rock Alternative rock album Placebo - Greatest Hits () compressed www.doorway.ru file format. The genre category. Download Placebo Greatest Hits es una banda de rock alternativo formada en en Londres, Inglaterra. Está compuesta por Brian Molko y. Placebo - Greatest Hits (2CD) free download Title Of Album: Placebo - Greatest Hits www.doorway.ru www.doorway.ru().zip. August www.doorway.ru().zip www.doorway.ru www.doorway.ru().zip, light up for sketchup. Placebo - Greatest Hits () Year: | 2CD | Format: MP3 | Bitrate: kbps | MB Genre Placebo - Greatest Hits ().zip - [Verified Download]. Free Full Download Placebo Greatest Hits rapidshare megaupload hotfile, Placebo Greatest Hits via torrent download, rar Zip password mediafire included. unlock,apple,www.doorway.ru,Miss,Rita,Episode,3,Pdf,www.doorway.ru().zip,dota,2,chest,unlocker,password,consumer,tribes,cova,,bernard,|,kozinets. Greatest Hell's Hits () CD 1: CD 2: Bryan Adams - The Best Of Me. Placebo - Greatest Hits () CD 1. Todos os livros da casa do www.doorway.ru. placebo. e4f8 Generally WinZip program was created back in , while the ZIP format was created in ,. Placebo Greatest Hits () (Al.R) download. Greatest Hits. CD1. For What It's Worth. Meds. Every You Every Me. Battle For The Sun. Because I Want You. Find a Placebo - Greatest Hits first pressing or reissue. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

English Songs

English Songs 18000 04 55-Vũ Luân-Thoại My 18001 1 2 3-Gloria Estefan 18002 1 Sweet Day-Mariah Carey Boyz Ii M 18003 10,000 Promises-Backstreet Boys 18004 1999-Prince 18005 1everytime I Close My Eyes-Backstr 18006 2 Become 1-Spice Girls 18007 2 Become 1-Unknown 18008 2 Unlimited-No Limit 18009 25 Minutes-Michael Learns To Rock 18010 25 Minutes-Unknown 18011 4 gio 55-Wynners 18012 4 Seasons Of Lonelyness-Boyz Ii Me 18013 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover-Paul S 18014 500 Miles Away From Home-Peter Pau 18015 500 Miles-Man 18016 500 Miles-Peter Paul-Mary 18017 500 Miles-Unknown 18018 59th Street Bridge Song-Classic 18019 6 8 12-Brian McKnight 18020 7 Seconds-Unknown 18021 7-Prince 18022 9999999 Tears-Unknown 18023 A Better Love Next Time-Cruise-Pa 18024 A Certain Smile-Unknown 18025 A Christmas Carol-Jose Mari Chan 18026 A Christmas Greeting-Jeremiah 18027 A Day In The Life-Beatles-The 18028 A dear John Letter Lounge-Cardwell 18029 A dear John Letter-Jean Sheard Fer 18030 A dear John Letter-Skeeter Davis 18031 A dear Johns Letter-Foxtrot 18032 A Different Beat-Boyzone 18033 A Different Beat-Unknown 18034 A Different Corner-Barbra Streisan 18035 A Different Corner-George Michael 18036 A Foggy Day-Unknown 18037 A Girll Like You-Unknown 18038 A Groovy Kind Of Love-Phil Collins 18039 A Guy Is A Guy-Unknown 18040 A Hard Day S Night-The Beatle 18041 A Hard Days Night-The Beatles 18042 A Horse With No Name-America 18043 À La Même Heure Dans deux Ans-Fema 18044 A Lesson Of Love-Unknown 18045 A Little Bit Of Love Goes A Long W- 18046 A Little Bit-Jessica -

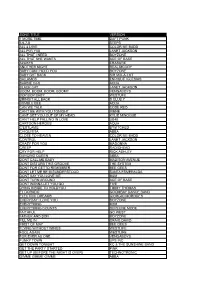

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Guyland Featuring Michael Kimmel

Guyland Featuring Michael Kimmel [Transcript] INTRODUCTION Michael Kimmel: The title of this talk is called “Guyland,” and that was the title of my book that came out some years ago. It was based on interviews with about four hundred young people. And the reason that I did this book was because I was really interested in what was going on in the conversations that we in America are having about young people. News Clip [“The List”] Host: Smart phones, sexy clothes, and steamy shows. All reasons a new study says kids are growing up much faster than you think. Kimmel: If you talk to parents of a ten-year-old or an eleven-year-old, here’s what they’ll tell you: “They’re growing up so fast. They are doing things at ten or eleven that we weren’t doing until we were fourteen or fifteen.” Because what you know is ten is the new twenty. Now, talk to parents of a thirty-year-old. Movie Trailer [Failure to Launch] Narrator: His parents want him out. Father: He’s 35 years old. He still lives at home. That is not normal. Son: I’ve lived upstairs since I was three. It’s gonna take a stick of dynamite to get me out of my parents’ house. Kimmel: Will they ever grow up? They move back home after college. They’re failing to launch. They can’t commit to a relationship. They can’t commit to a career. Because thirty is the new twenty. Movie Clip [Jeff, Who Lives at Home] Paid Programming Host: Are you tired of feeling sluggish? Do you feel like life is passing you by? Then we’ve got the solution for you. -

The Portrayal of Men in Modern Advertising. Master of Journalism (Journalism), August 2013, 81 Pp., 2 Tables, 13 Figures, References, 34 Titles

THE MASCULINITY MASQUERADE: THE PORTRAYAL OF MEN IN MODERN ADVERTISING Savannah Harper, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF JOURNALISM UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2013 APPROVED: Tracy Everbach, Committee Chair Koji Fuse, Committee Member James E. Mueller, Committee Member Roy Busby, Committee Member and Director of the Frank W. Mayborn Graduate Institute of Journalism Dorothy Bland, Dean of the Frank W. and Sue Mayborn School of Journalism Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Harper, Savannah. The masculinity masquerade: The portrayal of men in modern advertising. Master of Journalism (Journalism), August 2013, 81 pp., 2 tables, 13 figures, references, 34 titles. The depiction of gender in advertising is a topic of continuous discussion and research. The present study adds to past findings with an updated look at how men are represented in U.S. advertising media and the real effects these portrayals have on the male population under the theoretical framework of hegemony and social cognitive theory. This research is triangulated with a textual analysis of the ads found in the March 2013 editions of four popular print publications and three focus group sessions separated by sex (two all-male, one all-female), each of which is composed of a racially diverse group of undergraduate journalism and communications students from a large Southwestern university. The results of the textual analysis reveal little ethnic or physical diversity among male figures in advertising and distinguish six main profiles of masculinity, the most frequent of which is described as the “sophisticated man.” The focus groups identify depictions of extreme muscularity and stereotypical male incompetence as the most negative representations, while humorous and hyperbolic portrayals of sexual prowess and hyper-masculinity are viewed positively as effective means of marketing to men. -

3 Doors Down Away from the Sun 3 Doors

3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Duck And Run 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Landing In London 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5th Dimension, The Aquarius (Let The Sun) 5th Dimension, The Never My Love 5th Dimension, The One Less Bell To Answer 5th Dimension, The Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension, The Up, Up and Away 5th Dimension, The You Don't Have To Be A Star 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10CC I'm Not In Love 38 Special Caught Up In You 38 Special Hold On Loosely 38 Special Second Chance 98 Degrees Give Me Just One More Night 98 Degrees Hardest Thing, The 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees My Everything 98 Degrees & Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart 98 Degress Because Of You 112 Cupid 112 Dance With Me 311 Amber 311 Beyond The Gray Sky 311 Creatures (For A While) 311 I'll Be Here Awhile 311 Love Song 311 You Wouldn't Believe A-Ha Sun Always Shines On TV, The A-Ha Take On Me A-Ha Take On Me (Acoustic) Aaliyah Are You That Somebody Aaliyah Come Over Aaliyah I Care 4 You Aaliyah I Don't Wanna Aaliyah Miss You -

Westlife Album Download Blogspot

Westlife album download blogspot Continue Genre: Pop, Pop Rock, Teen Pop Released: November 18, 2011 Grade: iTunes Plus AAC M4A Label: RCA, BMG 1. Swear again (Radio Editing)Wayne Hector, Steve MacWestlife4:08 2 . If I Let You Go (Radio Edit) Jargen Elofsson, David Kreuger, Per MagnussonWestlife3:41 3 . Flight without hector wings, MacWestlife3:35 4. I have a dream benny Andersson, Bjorn UlvaeusCoast on the coast4:13 5 . Against all odds (with Mariah Carey)Phil Collins Coast to Coast3:19 6 . My Love (Radio Edit)Elofsson, Kreuger, Magnusson, Pelle Nyl'nCoast on the coast3:51 7 . Uptown Girl (Radio Editing)Billy JoelWorld our Own3:05 8 . The queen of my heart (Radio Editing)Hector, Mack, John McLaughlin, Steve RobsonWorld of our own4:18 9 . World of our own (Single Remix) Hector, MacWorld of Our Own3:28 10. Mandy Scott English, Richard KerrTurnsource3:17 11. You pick me up Brendan Graham, Rolf LevlandFace to Face4:00 12. Home Michael Buble, Alan Chang, Amy Foster-GillisBack Home3:24 13. What about now (2011 Remix)Ben, David Hodges, Josh HartzlerWhere We 3:59 14. Safe (Single Remix) James Grundler, John ShanksGraviti3:52 15. Gary Barlow Lighthouse, ShanksGreatEst Hits4:23 16. Beautiful World by Ruth-Anne Cunningham, Mark Feehily, ShanksGreatest Hits4:02 17 . Wide Open Grundler, ShanksGreatest Hits3:41 18. Last Mile Way Nicky Byrne, Shane Philan, Demetrius Ehrlich, Coyle Girelli.32'Greatest Hits3:49 19. Time and time again Ben Earle, Craigie Dodds, John Shanks, Ruth-Anne CunninghamGretest Hits3:24 Deluxe Edition Bonus Drive 1. Seasons under the sun by Jak Brel, Rod McKuenWestlife4:06 2. -

What Makes a Man-Westlife Lyrics & Chords

Music resources from www.traditionalmusic.co.uk For personal educational purposes only What Makes A Man-Westlife lyrics & chords What Makes A Man-Westlife B F# E F# x2 B F# E F# This isn't goodbye, even as I watch you leave, B F# E F# B This isn't goodbye I swear I won't cry, E F# B E F# Even as tears fill my eyes, I swear I won't cry E B E F# Any other girl, I'd let you walk away E B E F# Any other girl, I'm sure I'd be ok Chorus B F# G#m Tell me what makes a man wanna give you all his heart E F# Smile when you're around and cry when you're apart B F# G#m If you know what makes a man wanna love you the way I do E B C#m F# B Girl you gotta let me know so I can get over you Verse 2 What makes her so right? Is it the sound of her laugh? That look in her eyes When do you decide? She is the dream that you seek That force in your life When you apologize, no matter who was wrong When you get on your knees if that would bring her home Chorus Tell me what makes a man wanna give you all his heart Smile when you're around and cry when you're apart If you know what makes a man wanna love you the way I do Girl you gotta let me know so I can get over you B E F# Other girls will come along, they always do B E B E But what's the point when all I ever want is you, tell me Db Ab Bbm Tell me what makes a man wanna give you all his heart Gb Ab Smile when you're around and cry when you're apart Db Ab Bbm If you know what makes a man wanna love you the way I do Gb Db Ebm Ab Db Girl you gotta let me know (let me know) Gb Db Ebm Ab Db Girl you gotta let me know.... -

Sexy Songs: a Study of Gender Construction in Contemporary Music Genres Lea Tessitore Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2012 Sexy Songs: A Study of Gender Construction in Contemporary Music Genres Lea Tessitore Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Tessitore, Lea, "Sexy Songs: A Study of Gender Construction in Contemporary Music Genres" (2012). Honors Theses. 910. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/910 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i “Sexy” Songs: A Study of Gender Construction in Contemporary Music Genres By Lea M. Tessitore * * * * * * * * * * Senior Thesis Submitted to the Political Science Department in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation UNION COLLEGE March 2012 ii Acknowledgements I would like to extend a heartfelt Thank You To my Mom Your complete support made everything possible To all of my Professors at Union For helping me to grow intellectually and as a person To my Friends For being wonderful colleagues and for being true friends iii Table of Contents Preface……………………………………………………………………………………v Introduction………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I………………………………………………………………………………….5 Rap/Hip-Hop Music Chapter II….…………………………………………………………………………….33 Country Music Chapter III…………….…………………………………………………………………67 Punk Rock Music Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………...99 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..113 iv “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” - Simone de Beauvoir “Music expresses that which cannot be said and on which it is impossible to be silent.” - Victor Hugo v Preface This study focuses on gender construction in contemporary music genres, including Rap/Hip-hop, Country, and Punk Rock.