No Country for Workers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 of 5 Soumitra Chatterjee's B'day Chat 1/27/2012

Soumitra Chatterjee’s B’day Chat Page 1 of 5 Follow Us: Today's Edition | Thursday , January 19 , 2012 | Search IN TODAY'S PAPER Front Page > Entertainment > Story Front Page Nation Like 12 0 Calcutta Bengal Soumitra Chatterjee’s B’day Chat Opinion Soumitra Chatterjee, who turns 77 today, opens up to filmmaker s-Suman Ghosh on his work, his life International and his dreams. Only for t2. Business Sports Suman Ghosh: Kaku, how old are you going to turn Entertainment on January 19? Sudoku Sudoku New BETA Soumitra Chatterjee: Oh, that I don’t know! But I know Crossword my birth year… 1935. Jumble Gallery So, how do you approach ageing? Horse Racing Press Releases Frankly, the feeling of having to depend on someone Travel else is a bit difficult to deal with. I’m scared of WEEKLY FEATURES dependency. I have never really been dependent on Knowhow someone till now. Jobs Telekids Looking back, would you consider yourself ‘happy’? Personal TT 7days It’s difficult to say that. Happiness in life is occasional… Graphiti temporary. It is like an oasis, if it wasn’t present then life would be like walking in a desert. But talking about work, CITIES AND REGIONS sometimes I wonder how much I can actually give to the Metro society through the work I do…. Just a moment of North Bengal happiness. Northeast Jharkhand I have noticed a change in your attitude towards life Bihar in the last two years. Your usual vivacious self is absent. Why has that happened? Odisha ARCHIVES I would call that melancholia, because I am worried Since 1st March, 1999 about how long I can continue working. -

The Lost Ethos of Uttam-Suchitra Films: a ‘Nostalgic’ Review of Some Classic Romances from the Golden Era of Bengali Cinema Pramila Panda

The lost ethos of Uttam-Suchitra films: a ‘nostalgic’ review of some classic romances from the Golden Era of Bengali cinema Pramila Panda Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 194–200 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 194 Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 194-200 The lost ethos of Uttam-Suchitra films A ‘nostalgic’ review of some classic romances from the Golden Era of Bengali cinema Pramila Panda [email protected] www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 195 The mild tune of the sweet and soft song been able to touch every aspect of modern wrapped in sentimental love, “Ogo tumi je human society. This brings us to discussing the aamaar... Ogo tumi je aamaar” (You are status of romance or love in Bengali cinema mine, only mine…) from the Bengali movie half a century back. Harano Sur (Lost Melody) released in 1957 These divine qualities teach us the hymn of still buzzes pleasantries, not only inside my humanity and the art of living. These heavenly ear, but also at the centre of my mind. qualities are highly essential for the survival of Suchitra Sen and Uttam Kumar were the human society in peace and happiness. Of considered the ‘golden couple’ of Bengali films course, the world of cinema has not totally from 1953 to 1978. They left their special ignored the importance of these human identities by contributing the best of qualities to be reflected and utilized through themselves through their marvellous acting the different roles of different characters in talent. -

Sync Sound and Indian Cinema | Upperstall.Com 29/02/12 2:30 PM

Sync Sound and Indian Cinema | Upperstall.Com 29/02/12 2:30 PM Open Feedback Dialog About : Wallpapers Newsletter Sign Up 8226 films, 13750 profiles, and counting FOLLOW US ON RECENT Sync Sound and Indian Cinema Tere Naal Love Ho Gaya The lead pair of the film, in their real life, went in the The recent success of the film Lagaan has brought the question of Sync Sound to the fore. Sync Sound or Synchronous opposite direction as Sound, as the name suggests, is a highly precise and skilled recording technique in which the artist's original dialogues compared to the pair of the are used and eliminates the tedious process of 'dubbing' over these dialogues at the Post-Production Stage. The very first film this f... Indian talkie Alam Ara (1931) saw the very first use of Sync Feature Jodi Breakers Sound film in India. Since then Indian films were regularly shot I'd be willing to bet Sajid Khan's modest personality and in Sync Sound till the 60's with the silent Mitchell Camera, until cinematic sense on the fact the arrival of the Arri 2C, a noisy but more practical camera that the makers of this 'new particularly for outdoor shoots. The 1960s were the age of age B... Colour, Kashmir, Bouffants, Shammi Kapoor and Sadhana Ekk Deewana Tha and most films were shot outdoors against the scenic beauty As I write this, I learn that there are TWO versions of this of Kashmir and other Hill Stations. It made sense to shoot with film releasing on Friday. -

Wax Museum India

+91-9434189165 Wax Museum India https://www.indiamart.com/wax-museum-india/ Even as wax figures have become a synonym of Madame Tussauds across the world, a wax museum has been set up in Asansol city of West Bengal by an Indian artiste.Set up by Artist SUSANTA RAY, of West Bengal India. About Us Even as wax figures have become a synonym of Madame Tussauds across the world, a wax museum has been set up in Asansol city of West Bengal by an Indian artiste. Set up by Artist SUSANTA RAY, of West Bengal India, this museum has undoubtedly come as an inspiration from Madame Tussauds. The museum presently features wax figures of famous personalities including Mahatma Gandhi, Netaji Subhas, Rabindranath Tegore, Joyti Bose, Maradona, Sachin Tendulkar and many more... For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/wax-museum-india/aboutus.html WAX STATUES P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Kaji Nazrul Islam Wax Statue Utpal Dutta Wax Statue Pranab Mukherjee Wax Statue Joyti Bose Wax Statue P r o OTHER PRODUCTS: d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Uttam Kumar Wax Statue Diego Maradona Wax Statue Mahatma Gandhi Wax Statue Kapil Dev Wax Statue P r o OTHER PRODUCTS: d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Rabindra Nath Tegore Wax Ronaldinho Wax Statue Statue Sourav Ganguly Wax Statue Netaji Subhas Boses Wax Statue P r o OTHER PRODUCTS: d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Sachin Tendulker Wax Statue Jagadish Ch. -

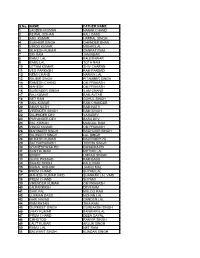

III) (28Th March, 2011 to 23Rd April, 2011) LIST of PARTICIPANTS

INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL FOREST ACADEMY MID CAREER TRAINING PHASE – V (III) (28th March, 2011 to 23rd April, 2011) LIST OF PARTICIPANTS S. No. Name (Shri/Smt./Dr.) Cadre YoA 1 GOVIND NARAYAN SINHA AGMUT 1983 2 LALRAMTHANGA AGMUT 1983 3 ASHOK KUMAR JAIN ANDHRA PRADESH 1983 4 KALATHURU SUGUNAKAR REDDY ANDHRA PRADESH 1983 5 MADDURI RAMA PRASAD ANDHRA PRADESH 1983 6 MATTA SUDHAKAR ANDHRA PRADESH 1983 7 PRASHANT KUMAR JHA ANDHRA PRADESH 1983 8 SURENDRA PANDEY ANDHRA PRADESH 1983 9 CAVOURIGHT PHANTO MARAK ASSAM MEGHALAYA 1983 10 SANTOSHPALSINGH ASSAMMEGHALAYA 1983 11 KAILASH CHANDRA BEBARTA CHHATTISGARH 1983 12 RABINDRA KUMAR SINGH CHHATTISGARH 1983 13 AKSHAYKUMARSAXENA GUJARAT 1983 14 ANOOP SHUKLA GUJARAT 1983 15 ASHOK KUMAR VARSHNEY GUJARAT 1983 16 KABOOL CHAND GUJARAT 1983 17 SATISH CHANDRA SRIVASTAV GUJARAT 1983 18 GULSHAN KUMAR HARYANA 1983 19 LALIT MOHAN HIMACHAL PRADESH 1983 20 SHAMSHER SINGH NEGI HIMACHAL PRADESH 1983 21 UTTAM KUMAR BANERJEE HIMACHAL PRADESH 1983 22 DHIRENDRA KUMAR JHARKHAND 1983 23 PRAKASH CHANDRA MISHRA JHARKHAND 1983 24 RAMESH RAMSAI HEMBROM JHARKHAND 1983 25 VENKATASUBBAIAHCHUKKAPALLI KARNATAKA 1983 26 VIDYASAGARGUDIPATI KARNATAKA 1983 27 KOOTTAPPURA GOPINATHAN NAIR KERALA 1983 MOHANLAL 28 THAVARUL PUTHIYADATH KERALA 1983 NARAYANANKUTTY 29 BRIJ MOHAN SINGH RATHOD MADHYA PRADESH 1982 30 JAJATI KISHORE MOHANTY MADHYA PRADESH 1983 31 KRISHNA PRATAP SINGH MADHYA PRADESH 1983 32 LALAN KUMAR CHAUDHARY MADHYA PRADESH 1983 33 LALIT MOHAN BELWAL MADHYA PRADESH 1983 34 MANGESH KUMAR TYAGI MADHYA PRADESH 1983 35 MANOJ KUMAR SINHA MADHYA PRADESH 1983 36 RAKESH KUMAR GUPTA MADHYA PRADESH 1983 37 TRIPURARI CHANDRA LOHANI MADHYA PRADESH 1983 38 BOBBA SIVAKUMAR REDDY MAHARASHTRA 1983 39 FARHAN SAJJAD JAFRY MAHARASHTRA 1983 40 KULDIP NARAYAN KHAWAREY MAHARASHTRA 1983 41 VINAY KUMAR SINHA MAHARASHTRA 1983 42 BALAPRASAD MANIPUR&TRIPURA 1983 S. -

Roll No/Sl No Name Father's Name Dob Reason

ROLL NO/SL NO NAME FATHER'S NAME DOB REASON FOR REJECTION 2100000107 DILEEP KUMAR PRAJAPATI RAM SHANKER 16/02/1993 NO ADVERTISEMENT NUMBER & CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2100000108 PARTHA MANNA BISWANATH MANNA 08/01/1990 NO ADVERTISEMENT NUMBER & CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2100000109 RAKESH KUMAR ROHITASHV 10/10/1990 NO ADVERTISEMENT NUMBER & CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2100000110 RUDRA PRATAP NAIK BASANTA NAIK 05/04/1991 NO ADVERTISEMENT NUMBER & CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2100000111 PRIYANKA KUMARI CHANDRA DEO RAI 27/12/1993 NO ADVERTISEMENT NUMBER & CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2100000112 ABHIJIT SINGH SATYADEO SINGH 14/08/1987 NO ADVERTISEMENT NUMBER & CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2100000113 JAYANTA MITRA KHOKAN MITRA 18/02/1992 NO ADVERTISEMENT NUMBER & CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2100000114 SEFALI KHATUN MD NOWSAD SK 28/02/1990 NO ADVERTISEMENT NUMBER & CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2100000115 PUTTILAL RAM SWAROOP 11/07/1988 NO ADVERTISEMENT NUMBER & CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2160000003 ASHIM LET MADAN LET 01/02/1992 NO CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2160000004 RAM PRAVESH THAKUR KHUSHI LAL THAKUR 28/02/1987 NO CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2160000005 CHARITRA BARMAN BHARAT BARMAN 01/12/1993 NO CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2160000006 AYUSH KUMAR BHOLA PRASAD 12/05/1990 NO CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2160000007 VIPIL KUMAR MAKKHAN LAL 08/04/1991 NO CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2160000008 BABLESH SAGAR MAL 05/10/1993 NO CATEGORY NUMBER IN APPLICATION 2160000009 SACHCHE LAL SAROJ SUSHEE KUMAR SAROJ -

S.No. NAME FATHER NAME 1 JAGDISH KUMAR NANAK CHAND

S.No. NAME FATHER NAME 1 JAGDISH KUMAR NANAK CHAND 2 KEWAL KISHAN KALI DASS 3 ANIL KUMAR HARPAL SINGH 4 SUKHBIR SINGH CHANDER BHAN 5 VINOD KUMAR MISHRI LAL 6 MUKESH KUMAR GANPAT RAM 7 SRI RAM JAMINDAR 8 RAMJI LAL KALESHWAR 9 BABU LAL TOTA RAM 10 UTTAM KUMAR SHIV CHARAN 11 VED PARKASH RAM PARSAD 12 NEMI CHAND NARAIN LAL 13 RAJBIR SINGH PITAMBER SINGH 14 RAMESH CHAND OM PRAKASH 15 MAHESH OM PRAKASH 16 SURENDER SINGH ILAM CHAND 17 RAJ KUMAR RAM AVTAR 18 NET RAM GOKUL SINGH 19 ANIL KUMAR RAM CHANDER 20 AMAR NATH RAM NATH 21 VIRENDER SINGH RAM SINGH 22 GAJENDER DEV VASUDEV 23 PARVINDER DEV BASU DEV 24 BAL KISHAN MANGAL RAM 25 VINOD KUMAR OM PRAKASH 26 MAHINDER SINGH RAGHUVIR SINGH 27 RAJINDER SINGH LAL SINGH 28 MUKESH KUMAR RAJENDER PD 29 SATYAPRAKASH TRIKHA SINGH 30 GYANESHWAR PD DWARIKA PD 31 SANT KUMAR MITHAN LAL 32 BOBBY UMRAO SINGH 33 GURU PRASAD RAM BABU 34 SAHAB SINGH KALE RAM 35 NAWAL KISHOR JHANU MAL 36 PREM CHAND SHYAM LAL 37 MAHESH KUMAR VAID SHANKAR LAL VAID 38 PREM CHAND SHYAMI 39 VIRENDER KUMAR OM PRAKASH 40 JAI PARKASH DEVI RAM 41 SHRI PAL MULOO RAM 42 LUXMAN DASS MOHAN LAL 43 HARI NIWAS GANDEN LAL 44 RAM RATAN TIKA RAM 45 GURMEET SINGH GURBAKSH SINGH 46 VIJAY KUMAR BANWARI LAL 47 PREM CHAND DEEN DAYAL 48 CHHOTOO RANVIR SINGH 49 LALIT KUMAR ARJUN SINGH 50 RAMJI LAL NET RAM 51 BALWANT SINGH KUNDAN SINGH 52 PAWAN KUMAR CHANDU LAL 53 GANJEDER SODAN 54 OM PARKASH KISHORI LAL 55 GOPAL MANGE LAL 56 AMIT KUMAR LT SH BIRBAL 57 KISHAN LAL BALU RAM 58 MUKESH KUMAR MOOL CHAND 59 VINOD KUMAR BABU LAL 60 DEPUTY SINGH DEEP CHAND 61 MUKESH -

A Postcolonial Iconi-City: Re-Reading Uttam Kumar's Cinema As

South Asian History and Culture ISSN: 1947-2498 (Print) 1947-2501 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsac20 A postcolonial iconi-city: Re-reading Uttam Kumar’s cinema as metropolar melodrama Sayandeb Chowdhury To cite this article: Sayandeb Chowdhury (2017): A postcolonial iconi-city: Re-reading Uttam Kumar’s cinema as metropolar melodrama, South Asian History and Culture, DOI: 10.1080/19472498.2017.1304090 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2017.1304090 Published online: 28 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsac20 Download by: [1.38.4.8] Date: 29 March 2017, At: 01:44 SOUTH ASIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2017.1304090 A postcolonial iconi-city: Re-reading Uttam Kumar’s cinema as metropolar melodrama Sayandeb Chowdhury School of Letters, Ambedkar University, Delhi, India ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Since the early years of India’s emergence into a ‘post-colony’, the Bengali cinema; Calcutta; possibilities of the popular in Bengali cinema had to be renegotiated modernity; melodrama; within the complex registers offered by a severely decimated cultural stardom economy of the region. It could be claimed that by early 1950s, Bengali cinema’s negotiation of a linguistic and spatial equivalent of ‘disputed’ and ‘lost’ nation led to it trying to constantly spatialize Calcutta, offering several possibilities to reinterpret the metropolar visuality in and of the postcolonial city. Calcutta provided Bengali cinema a habitation, a meta- phor of modernity and a spatial equivalent of a nation. -

Remembering the 'Unknown' Soumitra, a 'Cricketing Rival' to His Mentor

Remembering the ‘unknown’ Soumitra, a ‘cricketing rival’ to his mentor Satyajit Ray By - TIMESOFINDIA.COMSankha GhoshNov 16, 2020, 11:40 IST Soumitra Chattopadhyay and Satyajit Ray in shot discussion. Pic Courtesy: Twitter They had worked in as many as 14 films together in three decades. Some of Soumitra Chattopadhyay’s memorable works were crafted by none other than Satyajit Ray, whose films received critical acclaim and brought home several prestigious awards worldwide, and put India on the world cinema map. But not many people know Soumitra who passed away on November 15 after his long battle against COVID-19 once appeared as a rival to Ray, his mentor, on the 22 yards! “Soumitra Chattopadhyay was a big admirer of cricket. He, my father Dileep Mukherjee, and Soumendu Roy (Satyajit Ray’s most trusted cinematographer) used to live nearby and were addicted to sports. They would often meet each other to have a game of cricket. Not just the gentleman’s game but also badminton, football. They were sports fanatic and to see them trying their hands in sports was a treat to watch,” recalls former Bengal cricket team all-rounder Joydeep Mukherjee in an exclusive chat with ETimes. Have a close look at this particular photo from the 70s. You can see ahead of a charity match, it’s march past – among others Master Babloo (holding aloft the flag), Satyajit Ray leading the Hemanta Kumar XI, and Jahar Ganguly the captain of Kanan Devi’s XI. While Uttam Kumar walks just behind Satyajit Ray, it was Soumitra Chatterjee who can be seen as Jahar Ganguly’s deputy. -

Westminsterresearch the Digital Turn in Indian Film Sound

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The Digital Turn in Indian Film Sound: Ontologies and Aesthetics Bhattacharya, I. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr Indranil Bhattacharya, 2019. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] THE DIGITAL TURN IN INDIAN FILM SOUND: ONTOLOGIES AND AESTHETICS Indranil Bhattacharya A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2019 ii Abstract My project maps film sound practices in India against the backdrop of the digital turn. It is a critical-historical account of the transitional era, roughly from 1998 to 2018, and examines practices and decisions taken ‘on the ground’ by film sound recordists, editors, designers and mixers. My work explores the histories and genealogies of the transition by analysing the individual, as well as collective, aesthetic concerns of film workers migrating from the celluloid to the digital age. My inquiry aimed to explore linkages between the digital turn and shifts in production practices, notably sound recording, sound design and sound mixing. The study probes the various ways in which these shifts shaped the aesthetics, styles, genre conventions, and norms of image-sound relationships in Indian cinema in comparison with similar practices from Euro-American film industries. -

12 Convocation

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY CALICUT 12 TH CONVOCATION LIST OF GRADUANDS - UG Sl REG NO NAME CGPA CLASS/DIVISION DEPARTMENT DEGREE No 1 B110981AR AKSHAY MOHAN C M 6.47 SECOND CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE 2 B110077AR AKSHID RAJENDRAN 7.34 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE 3 B110948AR AMRUTHA KISHOR 6.94 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE 4 B110544AR ANEESURAHMAN.C A 6.51 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE 5 B110505AR APARNA RAMAKRISHNAN 6.73 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE APURVA DIVAKARAN 6 B110749AR 7.58 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE VATTAKANDY 7 B110326AR ARJUN SUNIL C M 7.01 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE 8 B110969AR ARUNIMA P M 7.71 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE 9 B110499AR ASWATHI C 7.34 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE 10 B110319AR ATHEELA 6.63 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE 11 B110735AR JEENA JOSEPH 7.41 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE FIRST CLASS 12 B110224AR JEENA MARY SAJIMON 8.02 WITH ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE DISTINCTION 13 B110191AR JIGISHA DHARMAN 6.92 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE MOHAMMED AFSAL 14 B110600AR 6.9 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE VADAKKAN MOHAMMED SALMAN 15 B110071AR 6.3 SECOND CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE SALEEM 16 B110770AR NEENU ALI 6.82 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE 17 B110223AR NISHAN NAZER K K 7.61 FIRST CLASS ARCHITECTURE BACHELOR -

Soumitra Chatterjee: a Legacy of True Bengal

© 2021 JETIR January 2021, Volume 8, Issue 1 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) SOUMITRA CHATTERJEE: A LEGACY OF TRUE BENGAL Ms Swagata Chakravorty Assistant Professor of the Department of Commerce, T.John College,Bangalore University B-402,Casa Ansal Apartment, No 18,Bannerghatta Road,Bangalore-560076 Abstract: On 14th of November, 2020, Bengal did not lose just an actor but a poet, philosopher, dramatist, painter, leftist and above all a great human being.Soumitra Chatterjee was mourned by millions of fans on this day as a person who had truly loved Bengal from its roots. As a responsible citizen he had evoked the essence of this language through the poetries, plays , movies and lots more. Awarded by the Dadasaheb Phalke and the Padma Bhushan are just a few as the list of honours is unending.The essay below is a tribute to the accomplished man, Soumitra Chatterjee. As the light faded at the `Minerva ‘ theatre , a tall handsome man made a princely appearance on the stage. There was perhaps a halo all around him.He was smart, energetic and above all a blessed actor. I was awestruck-Soumitra Chatterjee was there in front of me, enthralling the spectators with his unparalleled performance at the drama called`Tiktiki’.I came out of the spellbound state only at the curtain fall to realise that it was all a drama and not reality! Our amicable neighbourhood often held badminton matches amidst whatever little space we could get in the jungle of concrete. One fine evening, a car stopped and I found a tall person approaching us and enquired whether he also could join us in the game.