Water Vole Reintroduction on the Gwent Levels, Wales, UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Now Available Below Is a List of Outline Project Ideas and Proposals Where Organisations Are Looking for Other Partners to Collaborate With

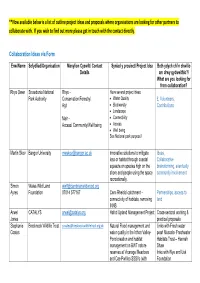

**Now available below is a list of outline project ideas and proposals where organisations are looking for other partners to collaborate with. If you wish to find out more please get in touch with the contact directly. Collaboration Ideas via Form Enw/Name Sefydliad/Organisation Manylion Cyswllt/ Contact Syniad y prosiect/ Project Idea Beth ydych chi’n chwilio Details am drwy gydweithio?/ What are you looking for from collaboration? Rhys Owen Snowdonia National Rhys – Have several project ideas: Park Authority Conservation/Forestry/ Water Quality £, Volunteers, Agri Biodiversity Contributions Landscape Mair – Connectivity Access/ Community/Well being Access Well being See National park purpose! Martin Skov Bangor University [email protected] Innovative solutions to mitigate Ideas, loss or habitat through coastal Collaborative squeeze on species high on the brainstorming, eventually shore and people using the space community involvement recreationally. Simon Wales Wild Land [email protected] Ayres Foundation 07814 577167 Cwm Rheidol catchment – Partnerships, access to connectivity of habitats, removing land INNS Arwel CATALYS [email protected] Hafod Upland Management Project Cross-sectoral working & Jones practical proposals Stephanie Brecknock Wildlife Trust [email protected] Natural Flood management and Links with Fresh water Coates water quality in the Irthon Valley- pearl Mussels- Freshwater Pond creation and habitat Habitats Trust – Hannah management on BWT nature Shaw reserves at Vicarage Meadows links with Wye and Usk and Cae Pwll bo SSSI’s (with Foundation consent from NRW due to meet January) Mike Kelly Shropshire Hills AONB [email protected] Upper Teme Wildlife/Habitat Bridge: We are currently working with Partnership 01743 254743 Natural England to develop this The upper River Teme forms the project in the Upper Teme boundary between Powys and Catchment. -

Gwent Wildlife Trust

Gwent Wildlife Trust 2009 Help us make Gwent a better place for people and wildlife Wildlife Trust Membership includes:- • A welcome pack full of information about your Trust. • Join by Direct Debit and receive a copy of the GWT Nature Reserves Guide worth £6. • A copy of our Natural World and Welsh Wildlife magazines, together with our informative local newsletter, delivered to your door three times a year. • Substantial discounts on GWT courses and events. • Most of all, the knowledge that you are doing something positive for local wildlife - helping to preserve and enhance your local patch for future generations! To join, simply complete and return the membership form overleaf and return it to the office. We’ll do the rest. Thank you. What do people think about Gwent Wildlife Trust courses, events and activities? Introduction to Bird Ringing “So very enjoyable – please hold this course every year” Dry Stone Walling “Good trainer (Terry Mead), spot-on training, friendly staff, lovely location, relaxed atmosphere” Winter Tree Identification “Excellent, knowledgeable tutors & put info across in an easily understandable way” Introduction to Spiders “A fascinating day – brilliant. My son and husband missed a fantastic day” Surveying for Dormice “Brilliant – thanks for providing such a privilege” Introduction to Bird Ringing “I was gutted that there were no big birds“ (From Thomas, aged 9. I guess we’re never going to please everybody!!!!) The work of GWT is generously supported by businesses, individuals and other grant awarding bodies. Below are just some of those who will keep us going in 2009! s • family e se • talks ven ur lks ts • co wa pra s • ctical activitie Stay closer to home, help wildlife, save money and get to know your county in 2009 This year, with the country gripped by financial crisis, and the During the year, Gwent Wildlife Trust offers a pound seemingly ever weaker, perhaps the time is right to re- programme of walks, talks, events, and training discover things closer to home? This guide is crammed full of courses throughout the county. -

Young, L.J., & Hammock E.A.D. (2007)

Update TRENDS in Genetics Vol.23 No.5 Research Focus On switches and knobs, microsatellites and monogamy Larry J. Young1 and Elizabeth A.D. Hammock2 1 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Center for Behavioral Neuroscience, 954 Gatewood Road, Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA 2 Vanderbilt Kennedy Center and Department of Pharmacology, 465 21st Avenue South, MRBIII, Room 8114, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37232, USA Comparative studies in voles have suggested that a formation. In male prairie voles, infusion of vasopressin polymorphic microsatellite upstream of the Avpr1a locus facilitates the formation of partner preferences in the contributes to the evolution of monogamy. A recent study absence of mating [7]. The distribution of V1aR in the challenged this hypothesis by reporting that there is no brain differs markedly between the socially monogamous relationship between microsatellite structure and mon- and socially nonmonogamous vole species [8]. Site-specific ogamy in 21 vole species. Although the study demon- pharmacological manipulations and viral-vector-mediated strates that the microsatellite is not a universal genetic gene-transfer experiments in prairie, montane and mea- switch that determines mating strategy, the findings do dow voles suggest that the species differences in Avpr1a not preclude a substantial role for Avpr1a in regulating expression in the brain underlie the species differences in social behaviors associated with monogamy. social bonding among these three closely related species of vole [3,6,9,10]. Single genes and social behavior Microsatellites and monogamy The idea that a single gene can markedly influence Analysis of the Avpr1a loci in the four vole species complex social behaviors has recently received consider- mentioned so far (prairie, montane, meadow and pine voles) able attention [1,2]. -

Non-Target Species Hazard Or Brodifacoum Use in Orchards for Meadow Vole Control

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Eastern Pine and Meadow Vole Symposia for March 1981 NON-TARGET SPECIES HAZARD OR BRODIFACOUM USE IN ORCHARDS FOR MEADOW VOLE CONTROL Mark H. Merson Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Winchester, Virginia Ross E. Byers Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Winchester, Virginia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/voles Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons Merson, Mark H. and Byers, Ross E., "NON-TARGET SPECIES HAZARD OR BRODIFACOUM USE IN ORCHARDS FOR MEADOW VOLE CONTROL" (1981). Eastern Pine and Meadow Vole Symposia. 58. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/voles/58 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Pine and Meadow Vole Symposia by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. NON-TARGET SPECIES HAZARD OF BRODIFACOUM USE IN ORCHARDS FOR MEADOW VOLE CONTROL Mark H. Merson and Ross E. Byers Winchester Fruit Research Laboratory Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Winchester, Virginia 22601 This year we entered into our second year of non-target species hazard assessment of Brodifacoum used (BFC; ICI Americas, Inc.) as an orchard rodenticide. The primary emphasis of this work has been to in- vestigate the effects of BFC on birds of prey through secondary poison- ing. The hazard level of BFC to raptors should be dependent on the levels found in post-treatment collections of meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus). -

Water Vole (Arvicola Amphibius) Abundance in Grassland Habitats of Glasgow

The Glasgow Naturalist (online 2018) Volume 27, Part 1 Water vole (Arvicola amphibius) abundance in grassland habitats of Glasgow R.A. Stewart1, C. Jarrett1, C. Scott2, S.A. White1 & D.J. McCafferty3 1 Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, G12 8QQ, Scotland, UK 2 Land and Environmental Services, Glasgow City Council, 231 George Street, Glasgow, G1 1RX, Scotland, UK 3 Scottish Centre for Ecology and the Natural Environment, Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, Rowardennan, Glasgow, G63 0AW, Scotland, UK 1 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT breeding season, demarcating the area with piles of Water vole (Arvicola amphibius) populations have droppings (latrines) and actively excluding other undergone a serious decline throughout the UK, and yet females, in contrast to the larger home range of the a stronghold of these small mammals is found in the males (Strachan & Moorhouse, 2006). The length of greater Easterhouse area of Glasgow. The water voles in habitat occupied is dependent on population density this location are mostly fossorial, living a largely with mean territory size measuring 30-150 m for subterranean existence in grasslands, rather than the females and 60-300 m for male home ranges at high and more typical semi-aquatic lifestyle in riparian habitats. low densities, respectively (Strachan & Moorhouse, In this study, we carried out capture-mark-recapture 2006). The mating season is triggered by increasing day surveys on water voles at two sites: Cranhill Park and length in early spring and extends from March through Tillycairn Drive. -

Guidelines for Wildlife and Traffic in the Carpathians

Wildlife and Traffic in the Carpathians Guidelines how to minimize the impact of transport infrastructure development on nature in the Carpathian countries Wildlife and Traffic in the Carpathians Guidelines how to minimize the impact of transport infrastructure development on nature in the Carpathian countries Part of Output 3.2 Planning Toolkit TRANSGREEN Project “Integrated Transport and Green Infrastructure Planning in the Danube-Carpathian Region for the Benefit of People and Nature” Danube Transnational Programme, DTP1-187-3.1 April 2019 Project co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) www.interreg-danube.eu/transgreen Authors Václav Hlaváč (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic, Member of the Carpathian Convention Work- ing Group for Sustainable Transport, co-author of “COST 341 Habitat Fragmentation due to Trans- portation Infrastructure, Wildlife and Traffic, A European Handbook for Identifying Conflicts and Designing Solutions” and “On the permeability of roads for wildlife: a handbook, 2002”) Petr Anděl (Consultant, EVERNIA s.r.o. Liberec, Czech Republic, co-author of “On the permeability of roads for wildlife: a handbook, 2002”) Jitka Matoušová (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic) Ivo Dostál (Transport Research Centre, Czech Republic) Martin Strnad (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic, specialist in ecological connectivity) Contributors Andriy-Taras Bashta (Biologist, Institute of Ecology of the Carpathians, National Academy of Science in Ukraine) Katarína Gáliková (National -

Recovery Plan for the Amargosa Vole

Recovery Plan for the Amargosa Vole (Microtus californicus scirpensis) ( As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the ~ Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use ofour land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environ mental and cultural values of our national parks ~, and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energyand mineral resourcesand works toassure that ~‘ theirdevelopment is in the best interests ofall our people. ~4 The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people ~<‘ who live in island Territories under U.S. administration. AMARGOSA VOLE (Microtus cahfornicus scirpensis) RECOVERY PLAN September, 1997 7— U.S. Department ofthe Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Region One, Portland, Oregon DISCLAIMER PAGE Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes prepared with the assistance ofrecovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. -

Mather Field Vernal Pools California Vole

Mather Field Vernal Pools common name California Vole scientific name Microtus californicus phylum Chordata class Mammalia order Rodentia family Muridae habitat common in grasslands, wetlands Jack Kelly Clark, © University of California Regents and wet meadows size up to 14 cm long excluding tail description The California Vole is covered with grayish-brown fur. Its ears and legs are short and it has pale feet. It has a cylindrical shape (like a toilet paper roll) with a tail that is 1/3 the length of the body. fun facts California Voles make paths through the grasslands leading to the mouths of their underground burrows. These surface "runways" are worn into the grass by daily travel. When chased by a predator, a vole can make a fast dash for the safety of its underground burrow using these cleared runways. If you walk quickly across the grassland you will often surprise a California Vole and see it scurry to its burrow. life cycle California Voles reach maturity in one month. Female voles have litters of four to eight young. In areas with abundant food and mild weather, each female can have up to five litters in a year. ecology The California Vole can dig its own underground burrow system but it often begins by using Pocket Gopher burrows. The tunnels are usually 1 to 5 meters long and up to one half meter below ground, with a nesting den somewhere inside. The ends of the burrows are left open. Many insects, spiders, centipedes, and other animals live in their burrows. Thus, the California Vole creates habitat for other species and the Pocket Gopher improves habitat for the vole. -

September 2012

Monmouthshire LDP Ecological Assessment of Alternative Sites September 2012 Issuing office Wyastone Business Park | Wyastone Leys | Monmouth | NP25 3SR T: 01600 891576 | W: www.bsg-ecology.com | E: [email protected] Client Monmouthshire County Council Job Monmouthshire LDP Report title Ecological Assessment of Alternative Sites Draft version/final FINAL File reference 4770.02_R_ag_190912.docx Name Position Date Originated Anna Gundrey Senior Ecologist 21 May 2012 Reviewed James Gillespie Partner 29 May 2012 Approved for issue to client James Gillespie Partner 29 May 2012 Issued to client Anna Gundrey Senior Ecologist 30 May 2012 Amendments Anna Gundrey Senior Ecologist 19 September 2012 Disclaimer This report is issued to the client for their sole use and for the intended purpose as stated in the agreement between the client and BSG Ecology under which this work was completed, or else as set out within this report. This report may not be relied upon by any other party without the express written agreement of BSG Ecology. The use of this report by unauthorised third parties is at their own risk and BSG Ecology accepts no duty of care to any such third party. BSG Ecology has exercised due care in preparing this report. It has not, unless specifically stated, independently verified information provided by others. No other warranty, express of implied, is made in relation to the content of this report and BSG Ecology assumes no liability for any loss resulting from errors, omissions or misrepresentation made by others. Any recommendation, opinion or finding stated in this report is based on circumstances and facts as they existed at the time that BSG Ecology performed the work. -

TVERC.18.371 TVERC Office Biodiversity Report

Thames Valley Environmental Records Centre Sharing environmental information in Berkshire and Oxfordshire BIODIVERSITY REPORT Site: TVERC Office TVERC Ref: TVERC/18/371 Prepared for: TVERC On: 05/09/2018 By: Thames Valley Environmental Records Centre 01865 815 451 [email protected] www.tverc.org This report should not to be passed on to third parties or published without prior permission of TVERC. Please be aware that printing maps from this report requires an appropriate OS licence. TVERC is hosted by Oxfordshire County Council TABLE OF CONTENTS The following are included in this report: GENERAL INFORMATION: Terms & Conditions Species data statements PROTECTED & NOTABLE SPECIES INFORMATION: Summary table of legally protected and notable species records within 1km search area Summary table of Invasive species records within 1km search area Species status key Data origin key DESIGNATED WILDLIFE SITE INFORMATION: A map of designated wildlife sites within 1km search area Descriptions/citations for designated wildlife sites Designated wildlife sites guidance HABITAT INFORMATION: A map of section 41 habitats of principal importance within 1km search area A list of habitats and total area within the search area Habitat metadata TVERC is hosted by Oxfordshire County Council TERMS AND CONDITIONS The copyright for this document and the information provided is retained by Thames Valley Environmental Records Centre. The copyright for some of the species data will be held by a recording group or individual recorder. Where this is the case, and the group or individual providing the data in known, the data origin will be given in the species table. TVERC must be acknowledged if any part of this report or data derived from it is used in a report. -

In Nests of the Common Mole, Talpa Europaea, in Central Europe

Exp Appl Acarol (2016) 68:429–440 DOI 10.1007/s10493-016-0017-6 Community structure variability of Uropodina mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) in nests of the common mole, Talpa europaea, in Central Europe 1 2 1 Agnieszka Napierała • Anna Ma˛dra • Kornelia Leszczyn´ska-Deja • 3 1,4 Dariusz J. Gwiazdowicz • Bartłomiej Gołdyn • Jerzy Błoszyk1,2 Received: 6 September 2013 / Accepted: 27 January 2016 / Published online: 9 February 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Underground nests of Talpa europaea, known as the common mole, are very specific microhabitats, which are also quite often inhabited by various groups of arthro- pods. Mites from the suborder Uropodina (Acari: Mesostigmata) are only one of them. One could expect that mole nests that are closely located are inhabited by communities of arthropods with similar species composition and structure. However, results of empirical studies clearly show that even nests which are close to each other can be different both in terms of the species composition and abundance of Uropodina communities. So far, little is known about the factors that can cause these differences. The major aim of this study was to identify factors determining species composition, abundance, and community structure of Uropodina communities in mole nests. The study is based on material collected during a long-term investigation conducted in western parts of Poland. The results indicate that the two most important factors influencing species composition and abundance of Uropodina communities in mole nests are nest-building material and depth at which nests are located. -

Investigating Evolutionary Processes Using Ancient and Historical DNA of Rodent Species

Investigating evolutionary processes using ancient and historical DNA of rodent species Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of London Royal Holloway University of London Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX Selina Brace November 2010 1 Declaration I, Selina Brace, declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, it is always clearly stated. Selina Brace Ian Barnes 2 “Why should we look to the past? ……Because there is nowhere else to look.” James Burke 3 Abstract The Late Quaternary has been a period of significant change for terrestrial mammals, including episodes of extinction, population sub-division and colonisation. Studying this period provides a means to improve understanding of evolutionary mechanisms, and to determine processes that have led to current distributions. For large mammals, recent work has demonstrated the utility of ancient DNA in understanding demographic change and phylogenetic relationships, largely through well-preserved specimens from permafrost and deep cave deposits. In contrast, much less ancient DNA work has been conducted on small mammals. This project focuses on the development of ancient mitochondrial DNA datasets to explore the utility of rodent ancient DNA analysis. Two studies in Europe investigate population change over millennial timescales. Arctic collared lemming (Dicrostonyx torquatus) specimens are chronologically sampled from a single cave locality, Trou Al’Wesse (Belgian Ardennes). Two end Pleistocene population extinction-recolonisation events are identified and correspond temporally with - localised disappearance of the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). A second study examines postglacial histories of European water voles (Arvicola), revealing two temporally distinct colonisation events in the UK.