Spirituality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argonaut #2 2019 Cover.Indd 1 1/23/20 1:18 PM the Argonaut Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society Publisher and Editor-In-Chief Charles A

1/23/20 1:18 PM Winter 2020 Winter Volume 30 No. 2 Volume JOURNAL OF THE SAN FRANCISCO HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOL. 30 NO. 2 Argonaut #2_2019_cover.indd 1 THE ARGONAUT Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society PUBLISHER AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Charles A. Fracchia EDITOR Lana Costantini PHOTO AND COPY EDITOR Lorri Ungaretti GRapHIC DESIGNER Romney Lange PUBLIcatIONS COMMIttEE Hudson Bell Lee Bruno Lana Costantini Charles Fracchia John Freeman Chris O’Sullivan David Parry Ken Sproul Lorri Ungaretti BOARD OF DIREctORS John Briscoe, President Tom Owens, 1st Vice President Mike Fitzgerald, 2nd Vice President Kevin Pursglove, Secretary Jack Lapidos,Treasurer Rodger Birt Edith L. Piness, Ph.D. Mary Duffy Darlene Plumtree Nolte Noah Griffin Chris O’Sullivan Richard S. E. Johns David Parry Brent Johnson Christopher Patz Robyn Lipsky Ken Sproul Bruce M. Lubarsky Paul J. Su James Marchetti John Tregenza Talbot Moore Diana Whitehead Charles A. Fracchia, Founder & President Emeritus of SFHS EXECUTIVE DIREctOR Lana Costantini The Argonaut is published by the San Francisco Historical Society, P.O. Box 420470, San Francisco, CA 94142-0470. Changes of address should be sent to the above address. Or, for more information call us at 415.537.1105. TABLE OF CONTENTS A SECOND TUNNEL FOR THE SUNSET by Vincent Ring .....................................................................................................................................6 THE LAST BASTION OF SAN FRANCISCO’S CALIFORNIOS: The Mission Dolores Settlement, 1834–1848 by Hudson Bell .....................................................................................................................................22 A TENDERLOIN DISTRIct HISTORY The Pioneers of St. Ann’s Valley: 1847–1860 by Peter M. Field ..................................................................................................................................42 Cover photo: On October 21, 1928, the Sunset Tunnel opened for the first time. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Addressing Fundamentalism by Legal and Spiritual Means

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE Addressing Fundamentalism by Legal and Spiritual Means By Dan Wessner Religion and Humane Global Governance by Richard A. Falk. New York: Palgrave, 2001. 191 pp. Gender and Human Rights in Islam and International Law: Equal before Allah, Unequal before Man? by Shaheen Sardar Ali. The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 2000. 358 pp. Religious Fundamentalisms and the Human Rights of Women edited by Courtney W. Howland. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999. 326 pp. The Islamic Quest for Democracy, Pluralism, and Human Rights by Ahmad S. Moussalli. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001. 226 pp. The post-Cold War era stands at a crossroads. Some sort of new world order or disorder is under construction. Our choice to move more toward multilateralism or unilateralism is informed well by inter-religious debate and international law. Both disciplines rightly challenge the “post- Enlightenment divide between religion and politics,” and reinvigorate a spiritual-legal dialogue once thought to be “irrelevant or substandard” (Falk: 1-8, 101). These disciplines can dissemble illusory walls between spiritual/sacred and material/modernist concerns, between realpolitik interests and ethical judgment (Kung 1998: 66). They place praxis and war-peace issues firmly in the context of a suffering humanity and world. Both warn as to how fundamentalism may subjugate peace and security to a demagogic, uncompromising quest. These disciplines also nurture a community of speech that continues to find its voice even as others resort to war. The four books considered in this essay respond to the rush and risk of unnecessary conflict wrought by fundamentalists. -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

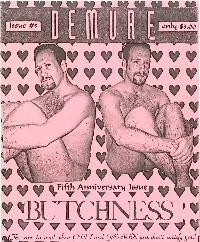

Fu ~ !;; Uad When

• v ~fu_~ !;;_uad when <D'llCJ and §CdVJ?E juit don't iatii{y you! [ FROM THE EDITOR Sloppy Sentimentality from your favorite person Here we go again! I myself can't believe this is #5. What staned out as a.fun little hobby has mushroom-clouded into a rather popular underground extravaganza. I'm now gelling more out ofstate orders than Minnesota sales. I've got/en groovy reviews from Wisconsin, Chicago and California and people send me free books and eds to review. I've even had the pleasure ofpissing offsome tight-asses (and will no doubtedly do it again with this issue!) Yes, zinedom is the life! Thanks/or reading this shit! Big news! In special celebration of the 5th Anniversary Issue, I am very hooored to bring back one ofmy original co-editors to write some columns. And I can even reveal his true identity. Yes, the bitch Sarah Tynge-Mayhem from DB #1 is none other than Mssr. Michael Moeglin, the laziest, most talented· writer I personally know (besides Troy Tradup and Michael Dahl). He's back to wreak havoc on DB and to generally ... entenain! Welcome back Michael! About this issue: In addition to our regular columnists (write in to which ones you like and don't like), this is a retro anniversary of sequels. Hence, a new queer quiz, more men I'm embarrassed to like, and another drag hag review. Ifyou like these, go back and order back issues for the originals (SSP ALERT!!!) I always keep back issues in stock (WARNING! SSP ALERT!!!) and some loyal readers are even ordering complete sets for the perfect Christmas gift (WARNING! SSP JS NOW AT A TOXIC LEVEL!!!). -

The Personal Politics of Spirituality: on the Lived Relationship Between Contemporary Spirituality and Social Justice Among Canadian Millennials

THE PERSONAL POLITICS OF SPIRITUALITY: ON THE LIVED RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CONTEMPORARY SPIRITUALITY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE AMONG CANADIAN MILLENNIALS by Galen Watts A thesis submitted to the Cultural Studies Graduate Program In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada April, 2016 Copyright © Galen Watts, 2016 ii Abstract In the last quarter century, a steadily increasing number of North Americans, when asked their religious affiliation, have self-identified as “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR). Resultantly, a wealth of literature on the subject of contemporary spirituality has recently emerged. Some suggest, generally, that we are seeing the emergence of a “progressive spirituality” that is potentially transformative and socially conscious. Conversely, there are scholars who have taken a more critical stance toward this recent cultural development, positing that contemporary spirituality is a byproduct of the self-obsessed culture which saturates the west, or that spirituality, at its worst, is simply a rebranding of religion in order to support consumer culture and the ideology of capitalism. One problem with the majority of this literature is that scholars have tended to offer essentialist or reductionist accounts of spirituality, which rely primarily on a combination of theoretical and textual analysis, ignoring both the lived aspect of spirituality in contemporary society and its variation across generations. This thesis is an attempt to mitigate some of this controversy whilst contributing to this burgeoning scholarly field. I do so by shedding light on contemporary spirituality, as it exists in its lived form. Espousing a lived religion framework, and using the qualitative data I collected from conducting semi-structured interviews with twenty Canadian millennials who consider themselves “spiritual but not religious,” I assess the cogency of the dominant etic accounts of contemporary spirituality in the academic literature. -

Teacher Collaboration Experiences: Finding the Extraordinary in the Everyday Moments

Portland State University PDXScholar Education Faculty Publications and Presentations Education 1-1-2011 Teacher Collaboration Experiences: Finding the Extraordinary in the Everyday Moments William A. Parnell Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/edu_fac Part of the Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Parnell, W. (2011). Teacher Collaboration Experiences: Finding the Extraordinary in the Everyday Moments. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 13(2). This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. 6/25/13 ECRP. Teacher Collaboration Experiences: Finding the Extraordinary in the Everyday Moments Share Home Journal Contents Issue Contents Volume 13 Number 2 ©The Author(s) 2011 Teacher Collaboration Experiences: Finding the Extraordinary in the Everyday Moments Will Parnell Portland State University Abstract In this report of a phenomenological study, the co-director of a U.S. early childhood program describes and reflects on the interrelationship of his collaborative work with teachers, staff members’ documentation of children’s work and school events, and his own professional development activities. The author presents and discusses three events that took place over the course of a year. In the first narrative episode, his recent professional development experience at a program inspired by the Reggio Emilia approach enables him to support a teacher who is feeling discouraged about challenging situations in her classroom. -

Rev. Dr. Robert E. Shore-Goss

A division of WIPF and STOCK Publishers CASCADE Books wipfandstock.com • (541) 344-1528 GOD IS GREEN An Eco-Spirituality of Incarnate Compassion Robert E. Shore-Goss At this time of climate crisis, here is a practical Christian ecospirituality. It emerges from the pastoral and theological experience of Rev. Robert Shore-Goss, who worked with his congregation by making the earth a member of the church, by greening worship, and by helping the church building and operations attain a carbon neutral footprint. Shore-Goss explores an ecospirituality grounded in incarnational compassion. Practicing incarnational compassion means following the lived praxis of Jesus and the commission of the risen Christ as Gardener. Jesus becomes the “green face of God.” Restrictive Christian spiritualities that exclude the earth as an original blessing of God must expand. is expansion leads to the realization that the incarnation of Christ has deep roots in the earth and the fleshly or biological tissue of life. is book aims to foster ecological conversation in churches and outlines the following practices for congregations: meditating on nature, inviting sermons on green topics, covenanting with the earth, and retrieving the natural elements of the sacraments. ese practices help us recover ourselves as fleshly members of the earth and the network of life. If we fall in love with God’s creation, says Shore-Goss, we will fight against climate change. Robert E. Shore-Goss has been Senior Pastor and eologian of MCC United Church of Christ in the Valley (North Hollywood, California) since June 2004. He has made his church a green church with a carbon neutral footprint. -

Developments and Applications of Cyclic Cell Penetrating

DEVELOPMENTS AND APPLICATIONS OF CYCLIC CELL PENETRATING PEPTIDES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ziqing Qian Graduate Program in Chemistry The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Dehua Pei, Advisor Professor Venkat Gopalan Professor Dennis Bong Copyright by Ziqing Qian 2014 ABSTRACT Cell penetrating peptides (CPP) have been featured as a powerful delivery vector for the intracellular delivery of membrane-impermeable cargoes. This dissertation primarily focuses on the development, characterization, and application of a new class of CPP: cyclic cell penetrating peptides. Prompted by long-standing interests of the Pei group in developing cyclic peptides as biological tools and potential therapeutics, I describe our exploration of the permeability properties of the cyclic peptides, leading to the discovery that cyclic peptides with a short sequence motif rich in arginine and hydrophobic residues display significantly higher cellular permeability than their linear counterparts. The resulting cyclic CPP also translocated into the mammalian cell interior at significantly higher efficiencies than canonical arginine-rich linear CPPs. Subsequent internalization mechanistic investigations involving model lipid vesicles and pharmacological inhibitors, as well as genetic mutations, which perturb individual internalization steps, have shown conclusively that cyclic CPPs enter cells through endocytosis and are capable of escaping from early endosomes. To explore the utilities of cyclic CPP as cytoplasmic delivery vehicles, we developed endocyclic, exocyclic, and bicyclic delivery methods to deliver monocyclic peptides, bicyclic peptides, and proteins into cells. Biologically active cargoes, such as fluorogenic phosphatase substrates, phosphatase inhibitors, green ii fluorescent protein, and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B were efficiently delivered by cyclic CPP. -

Freire, Dialogue, and Spirituality in the Composition Classroom

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 Teaching With Spirit: Freire, Dialogue, And Spirituality In The ompC osition Classroom Justin Vidovic Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Other Education Commons Recommended Citation Vidovic, Justin, "Teaching With Spirit: Freire, Dialogue, And Spirituality In The ompositC ion Classroom" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 121. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. TEACHING WITH SPIRIT: FREIRE, DIALOGUE, AND SPIRITUALITY IN THE COMPOSITION CLASSROOM by JUSTIN VIDOVIC DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2010 MAJOR: ENGLISH Approved by: __________________________ Advisor Date __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ DEDICATION Thank you to the friends from the spiritual, artistic, and teaching communities I joined, from whom I have learned new values and ways of being. I owe a debt I can never really repay for everything I have been given. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to David Magidson, Claire Shinkman, Jeffery Steiger, everyone at Wild Swan Theater, Karen Pogue, and Stacey Peckens for artistic mentoring in things other than academic writing. Amongst other things, they all said, and modeled for me, “Trust yourself and have some faith, and you’ll make something beautiful.” Thanks to John Mead and David Schaafsma for telling me how important sharing honest academic work can be. -

Why and How to Study Spirituality

MAPPING A FIELD: WHY AND HOW TO STUDY SPIRITUALITY BY COURTNEY BENDER & OMAR MCROBERTS CO-CHAIRS, WORKING GROUP ON SPIRITUALITY, POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT, AND PUBLIC LIFE OCTOBER, 2012 What does "spirituality" mean in America today, and how can social scientists best investigate it? This paper identifies new approaches to the study of American spirituality and emergent horizons for interdisciplinary scholarship. In contrast to the longstanding sociological practice that identifies spirituality in distinction or comparison to religion, we begin by inquiring into the processes through which contemporary uses of the categories religion and spirituality have taken on their current values, how they align with different types of political, cultural, and social action, and how they are articulated within public settings.1 In so doing, we draw upon and extend a growing body of research that offers alternatives to predominant social scientific understandings of spirituality in the United States, which, we believe, are better suited to investigating its social, cultural, and political implications. Taken together, they evaluate a more expansive range of religious and spiritual identities and actions, and, by placing spirituality and religion, as well as the secular, in new configurations, ought to reset scholars’ guiding questions on the subject of the spiritual. This paper also highlights methods and orientations that we believe are germane to the concerns and questions that motivated our recent project on spirituality, public life, and politics in America, but that also extend beyond them. It draws into relief the space that has been opened up by recent analyses of spirituality and identifies the new questions and problems that are taking shape as a result. -

Bridges Fall 2004

BRIDGES FALL 2004 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY • DAVID M. KENNEDY CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Life in a Global Village Kennedy Center Fifth Annual Photography Contest FIRST PLACE “Agua,” Genevieve Brown Comedero, Mexico BRIDGES FALL 2004 2 Director’s Message FEATURES 4 Life in a Global Village “All seek to explain the common human experiences of life—e.g., birth, death, old age, hunger, sexual urges, marriage, wealth, poverty, and disease.” Roger R. Keller, Richard L. Evans Professor of Religious Understanding, BYU 12 Socially Engaged Spirituality: Challenges in Emerging local and Global Development Strategies “For me, the greatest challenge facing humanity is that our future is too narrowly defi ned—there is only one goal of economic growth and only one path to attain that goal.” Sulak Sivaraksa, Thai intellectual and social critic 18 Beyond the Border “We think this will help us reach a new audience, and it will help us fulfi ll an untapped portion of the center’s mission—a national outreach through produc- tion of information.” Jocelyn Stayner PERSONALITY PROFILE 22 Rabbi Frederick L. Wenger—Midwest to Far East “Life as a rabbi is like being called as a bishop—only it’s for life!” J. Lee Simons COMMUNITIES 26 Campus 31 Alumni 34 World 40 Trends Jeffrey F. Ringer, PUBLISHER Cory W. Leonard, MANAGING EDITOR J. Lee Simons, EDITOR Published by the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. Jocelyn Stayner, ASSISTANT EDITOR Copyright 2004 by Brigham Young University. All rights reserved. All communications should be sent to Bridges, Jamie L. Huish, ASSISTANT EDITOR 237 HRCB, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602.