A Brief History of Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: the Image

Burlesquing “Otherness” 101 Burlesquing “Otherness” in Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: The Image of the Indian in John Brougham’s Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs (1847) and Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage (1855). Zoe Detsi-Diamanti When John Brougham’s Indian burlesque, Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs, opened in Boston at Brougham’s Adelphi Theatre on November 29, 1847, it won the lasting reputation of an exceptional satiric force in the American theatre for its author, while, at the same time, signaled the end of the serious Indian dramas that were so popular during the 1820s and 1830s. Eight years later, in 1855, Brougham made a most spectacular comeback with another Indian burlesque, Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage, an “Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized, and Demi-savage Extravaganza,” which was produced at Wallack’s Lyceum Theatre in New York City.1 Both plays have been invariably cited as successful parodies of Augustus Stone’s Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) and the stilted acting style of Edwin Forrest, and the Pocahontas plays of the first half of the nineteenth century. They are sig- nificant because they opened up new possibilities for the development of satiric comedy in America2 and substantially contributed to the transformation of the stage picture of the Indian from the romantic pattern of Arcadian innocence to a view far more satirical, even ridiculous. 0026-3079/2007/4803-101$2.50/0 American Studies, 48:3 (Fall 2007): 101-123 101 102 Zoe Detsi-Diamanti -

Discovery & Geology of the Guinness World Record Lake Copper, Lake

DISCOVERY AND GEOLOGY OF THE GUINNESS WORLD RECORD LAKE COPPER, LAKE SUPERIOR, MICHIGAN by Theodore J. Bornhorst and Robert J. Barron 2017 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J. and Barron, R. J., 2017, Discovery and geology of the Guinness world record Lake Copper, Lake Superior, Michigan: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 2, 8 p. This document was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. This is version 2 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 2 first published online in 2016. The Copper Pavilion at the A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum exhibits a 19-ton mass of native copper recovered on the bottomland of Lake Superior on permanent loan from the State of Michigan, Department of Natural Resources. Discovery This Guinness World Record holding tabular mass of native copper, weighing approximately 19 tons, was recovered from the bottomlands of Lake Superior and is now on exhibit in the Copper Pavilion at the A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum of Michigan Tech referred to here as the "Lake Copper." Figure 1: Location of the Lake Copper shown in context with the generalized bedrock geology along the flank of the Midcontinent rift system (after Bornhorst and Lankton, 2009). 1 It was discovered in July of 1991 by local divers Bob Barron and Don Kauppi on the bottomlands of Lake Superior in about 30 feet of water northwest of Jacob’s Creek, Great Sand Bay between Eagle River and Eagle Harbor (Figure 1 and 2). The tabular Lake Copper was horizontal when discovered rather than vertical in the vein as it had fallen over. -

In Search of the Indiana Lenape

IN SEARCH OF THE INDIANA LENAPE: A PREDICTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE LENAPE LIVING ALONG THE WHITE RIVER IN INDIANA FROM 1790 - 1821 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY JESSICA L. YANN DR. RONALD HICKS, CHAIR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 Table of Contents Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Research Goals ............................................................................................................................ 1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 2: Theory and Methods ................................................................................................. 6 Explaining Contact and Its Material Remains ............................................................................. 6 Predicting the Intensity of Change and its Effects on Identity................................................... 14 Change and the Lenape .............................................................................................................. 16 Methods .................................................................................................................................... -

“America” on Nineteenth-Century Stages; Or, Jonathan in England and Jonathan at Home

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME by Maura L. Jortner BA, Franciscan University, 1993 MA, Xavier University, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by It was defended on December 6, 2005 and approved by Heather Nathans, Ph.D., University of Maryland Kathleen George, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Attilio Favorini, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, Ph.D., Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Maura L. Jortner 2005 iii PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME Maura L. Jortner, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation, prepared towards the completion of a Ph.D. in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, examines “Yankee Theatre” in America and London through a post-colonial lens from 1787 to 1855. Actors under consideration include: Charles Mathews, James Hackett, George Hill, Danforth Marble and Joshua Silsbee. These actors were selected due to their status as iconic performers in “Yankee Theatre.” The Post-Revolutionary period in America was filled with questions of national identity. Much of American culture came directly from England. American citizens read English books, studied English texts in school, and watched English theatre. They were inundated with English culture and unsure of what their own civilization might look like. -

Baltic Towns030306

Seventeenth Century Baltic Merchants is one of the most frequented waters in the world - if not the Tmost frequented – and has been so for the last thousand years. Shipping and trade routes over the Baltic Sea have a long tradition. During the Middle Ages the Hanseatic League dominated trade in the Baltic region. When the German Hansa definitely lost its position in the sixteenth century, other actors started struggling for the control of the Baltic Sea and, above all, its port towns. Among those coun- tries were, for example, Russia, Poland, Denmark and Sweden. Since Finland was a part of the Swedish realm, ”the eastern half of the realm”, Sweden held positions on both the east and west coasts. From 1561, when the town of Reval and adjacent areas sought protection under the Swedish Crown, ex- pansion began along the southeastern and southern coasts of the Baltic. By the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648, Sweden had gained control and was the dom- inating great power of the Baltic Sea region. When the Danish areas in the south- ern part of the Scandinavian Peninsula were taken in 1660, Sweden’s policies were fulfilled. Until the fall of Sweden’s Great Power status in 1718, the realm kept, if not the objective ”Dominium Maris Baltici” so at least ”Mare Clausum”. 1 The strong military and political position did not, however, correspond with an economic dominance. Michael Roberts has declared that Sweden’s control of the Baltic after 1681 was ultimately dependent on the good will of the maritime powers, whose interests Sweden could not afford to ignore.2 In financing the wars, the Swedish government frequently used loans from Dutch and German merchants.3 Moreover, the strong expansion of the Swedish mining industries 1 Rystad, Göran: Dominium Maris Baltici – dröm och verklighet /Mare nostrum. -

Sir David William Smith's 1790 Manuscript Plan

No. 5 Rough Scetch of the King’s Domain at Detroit Clements Library January 2018 OccasionalSCETCH OF THE KING’S DOMAINBulletins AT DETROIT Occasional — Louie Miller and Brian Bulletins Leigh Dunnigan nyone familiar with the history of the Clements Library sions—Books, Graphics, Manuscripts, and Maps—have always knows that we have a long tradition of enthusiastic collect- shared that commitment to enhancing our holdings for the benefit Aing. Our founder and our four directors (in 94 years) have of the students and scholars who come here for their research. We been dedicated to the proposition that an outstanding research buy from dealers and at auction; we cultivate collectors and other library must expand its holdings to maintain its greatness, and we individuals to think about the Library as a home for their historical have used every means available to pursue interesting primary materials; and we are constantly on watch for anything, from single sources on early America. The curators of our four collecting divi- items to large collections, that we can acquire to help illuminate Fort Lernoult, the linch pin of Detroit’s defenses, was rushed to completion during 1778–1779. It was a simple earthen redoubt with four half-bastions and a ditch surrounded by an abattis (an entanglement of tree branches placed to impede an infantry assault). The “swallow tail” fortification on the north (top) side of the fort was designed but never completed. Fort Lernoult stood at what is today the intersection of Fort and Shelby streets in downtown Detroit. This is a detail of the Smith plan of 1790. -

REFUNDING BONDS of MACKINAC BRIDGE AUTHORITY; TRANSFER of AUTHORITY to STATE HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT Act 13 of 1966

REFUNDING BONDS OF MACKINAC BRIDGE AUTHORITY; TRANSFER OF AUTHORITY TO STATE HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT Act 13 of 1966 AN ACT to implement the provisions of section 14 of the schedule and temporary provisions of the constitution of this state by providing for the issuance and sale of full faith and credit bonds of the state to refund the outstanding bonds heretofore issued by the Mackinac bridge authority and upon such refunding to abolish the Mackinac bridge authority and to transfer the operation, maintenance, repair and replacement of the Mackinac bridge to the state highway department with power to fix and collect tolls, fees and charges for the use of the bridge, its services and facilities. History: 1966, Act 13, Imd. Eff. Apr. 6, 1966. The People of the State of Michigan enact: 254.361 Refunding bonds; issuance, purpose. Sec. 1. The state may borrow money and issue its refunding bonds for the purpose of refunding the following outstanding bonds issued by the Mackinac bridge authority, and agency and instrumentality of this state created by Act No. 21 of the Public Acts of the Extra Session of 1950, being sections 254.301 to 254.304 of the Compiled Laws of 1948, pursuant to Act No. 214 of the Public Acts of 1952, as amended, being sections 254.311 to 254.331 of the Compiled Laws of 1948, and a certain indenture between the Mackinac bridge authority and the Detroit trust company, dated July 1, 1953: (a) Bridge revenue bonds, series A (Mackinac straits bridge), dated July 1, 1953, in the principal sum of $79,800,000.00; (b) Bridge revenue bonds, series B (Mackinac straits bridge), dated July 1, 1953, in the principal sum of $20,000,000.00. -

Michigan and the Civil War Record Group 57

Michigan and the Civil War Record Group 57 Entry 1: Books Belknap, Charles E., History of the Michigan Organizations at Chickamauga, Chattanooga, and Missionary Ridge, 1863 Ellis, Helen H., Michigan in the civil War: A Guide to the Material in Detroit Newspapers 1861- 1866 Genco, James G., To the Sound Of Musketry and the Tap of the Drum Michigan and the Civil War: An Anthology Michigan at Gettysburg, July 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, 1863. June 12th, 1889 Michigan Soldiers and Sailors, Alphabetical Index, Civil War, 1861-1865 Nolan, Alan T., The Iron Brigade: A Military History Record of Service of Michigan Volunteers in the Civil War1861-1865, Vol. 43Engineers and Mechanics Record of Service of Michigan Volunteers in the Civil War1861-1865, Vol.33 Third Michigan Cavalry Record of Service of Michigan Volunteers in the Civil War1861-1865, Vol. 24 Twenty-Fourth Michigan Infantry Record of Service of Michigan Volunteers in the Civil War1861-1865, Vol. 2 Second Michigan Infantry Record of Service of Michigan Volunteers in the Civil War1861-1865Vol. 1 First Michigan Infantry Record of Service of Michigan Volunteers in the Civil War 1861-1865, Vol. 4 Fourth Michigan Infantry Record of Service of Michigan Volunteers in the Civil War 1861-1865, Vol. 5 Fifth Michigan Infantry Robertson, Jno., Michigan in the War War Papers-Michigan Commandery L.L., Vol. I-October 6, 1886-April 6, 1893, Broadfoot Publishing, 1993 War Papers-Michigan Comandery L.L., Vol. II-December 7, 1893-May 5, 1898 Broadfoot Publishing, 1993 Entry 2: Pamphlets Beeson, Ed. Lewis, Impact of the Civil War on the Presbyterian Church in Michigan, Micigan Civil War Centennial Observer Commission, 1965 Beeson, Lewis, Ed. -

A New Jersey Haven for Some Acculturated Lenape of Pennsylvania During the Indian Wars of the 1760S

322- A New Jersey Haven for Some Acculturated Lenape of Pennsylvania During the Indian Wars of the 1760s Marshall Joseph Becker West Chester University INTRODUCTION Accounts of Indian depredations are as old as the colonization of the New World, but examples of concerted assistance to Native Americans are few. Particu- larly uncommon are cases in which whites extended aid to Native Americans dur- ing periods when violent conflicts were ongoing and threatening large areas of the moving frontier. Two important examples of help being extended by the citizens of Pennsyl- vania and NewJersey to Native Americans of varied backgrounds who were fleeing from the trouble-wracked Pennsylvania colony took place during the period of the bitter Indian wars of the 1760s. The less successful example, the thwarted flight of the Moravian converts from the Forks of Delaware in Pennsylvania and their attempted passage through New Jersey, is summarized here in the appendices. The second and more successful case involved a little known cohort of Lenape from Chester County, Pennsylvania. These people had separated from their native kin by the 1730s and taken up permanent residence among colonial farmers. Dur- ing the time of turmoil for Pennsylvanians of Indian origin in the 1760s, this group of Lenape lived for seven years among the citizens of NewJersey. These cases shed light on the process of acculturation of Native American peoples in the colonies and also on the degree to which officials of the Jersey colony created a relatively secure environment for all the people of this area. They also provide insights into differences among various Native American groups as well as between traditionalists and acculturated members of the same group.' ANTI-NATIVE SENTIMENT IN THE 1760S The common English name for the Seven Years War (1755-1763), the "French and Indian War," reflects the ethnic alignments and generalized prejudices reflected in the New World manifestations of this conflict. -

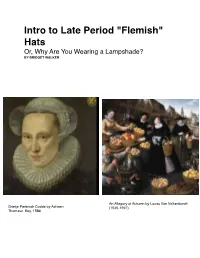

"Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? by BRIDGET WALKER

Intro to Late Period "Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? BY BRIDGET WALKER An Allegory of Autumn by Lucas Van Valkenborch Grietje Pietersdr Codde by Adriaen (1535-1597) Thomasz. Key, 1586 Where Are We Again? This is the coast of modern day Belgium and The Netherlands, with the east coast of England included for scale. According to Fynes Moryson, an Englishman traveling through the area in the 1590s, the cities of Bruges and Ghent are in Flanders, the city of Antwerp belongs to the Dutchy of the Brabant, and the city of Amsterdam is in South Holland. However, he explains, Ghent and Bruges were the major trading centers in the early 1500s. Consequently, foreigners often refer to the entire area as "Flemish". Antwerp is approximately fifty miles from Bruges and a hundred miles from Amsterdam. Hairstyles The Cook by PieterAertsen, 1559 Market Scene by Pieter Aertsen Upper class women rarely have their portraits painted without their headdresses. Luckily, Antwerp's many genre paintings can give us a clue. The hair is put up in what is most likely a form of hair taping. In the example on the left, the braids might be simply wrapped around the head. However, the woman on the right has her braids too far back for that. They must be sewn or pinned on. The hair at the front is occasionally padded in rolls out over the temples, but is much more likely to remain close to the head. At the end of the 1600s, when the French and English often dressed the hair over the forehead, the ladies of the Netherlands continued to pull their hair back smoothly. -

The Mckee Treaty of 1790: British-Aboriginal Diplomacy in the Great Lakes

The McKee Treaty of 1790: British-Aboriginal Diplomacy in the Great Lakes A thesis submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements for MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN Saskatoon by Daniel Palmer Copyright © Daniel Palmer, September 2017 All Rights Reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History HUMFA Administrative Support Services Room 522, Arts Building University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i Abstract On the 19th of May, 1790, the representatives of four First Nations of Detroit and the British Crown signed, each in their own custom, a document ceding 5,440 square kilometers of Aboriginal land to the Crown that spring for £1200 Quebec Currency in goods. -

Mackinac Bridge Enters the Busy Season for Traffic and for Maintenance Work

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TUESDAY, MAY 25, 2021 CONTACT: Kim Nowack, Mackinac Bridge Authority, 906-643-7600 Mackinac Bridge enters the busy season for traffic and for maintenance work May 25, 2021 -- As traffic picks up on the Mackinac Bridge for the traditional increase in warmer season travel, so does the work required to maintain this engineering icon. Contractor Seaway Painting is wrapping up five seasons devoted to stripping and repainting the bridge's twin ivory towers. At the same time, the Mackinac Bridge Authority's (MBA) team of dedicated maintenance staff is out on the bridge deck, replacing pieces of the original decking, repairing deck joints, and cleaning off a winter's worth of grit tracked onto the bridge. "Like with road work and maintenance anywhere else, the season for taking care of the Mackinac Bridge coincides with the peak of tourism travel in northern Michigan," said MBA Executive Secretary Kim Nowack. "We realize the views of the Straits of Mackinac are tempting, but we need customers to focus their attention on driving, especially when passing work zones on the bridge." Delays for work on the bridge are generally minimal, as most lane closures are removed for holidays and peak traffic periods, but in some cases those lane closures must remain in place even when traffic picks up. "We're all in a hurry to get where we're going, particularly when we're on vacation, but it's critically important that drivers slow down and set aside any distractions when they are passing through one of our work zones," Nowack said.