From...Bugliari Soccer – the Beginning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Record Book 5 Single-Season Records

PROGRAM RECORDS TEAM INDIVIDUAL Game Game Goals .......................................................11 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Goals .................................................. 5, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 ............................................................11 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 Assists ................................................. 4, Damian Silvera vs. UNC, 9/27/92 Assists ......................................................11 vs. Virginia Tech, 9/14/94 ..................................................... 4, Richie Williams vs. VCU, 9/13/89 Points .................................................................... 30 vs. VCU, 9/13/89 ........................................... 4, Kris Kelderman vs. Charleston, 9/10/89 Goals Allowed .................................................12 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 ...........................................4, Chick Cudlip vs. Wash. & Lee, 11/13/62 Margin of Victory ....................................11-0 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Points ................................................ 10, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 Fastest Goal to Start Match .........................................................11-0 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 .................................:09, Alecko Eskandarian vs. American, 10/26/02* Margin of Defeat ..........................................12-0 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 Largest Crowd (Scott) .......................................7,311 vs. Duke, 10/8/88 *Tied for 3rd fastest in an NCAA Soccer Game Largest Crowd (Klöckner) ......................7,906 -

Major League Soccer-Historie a Současnost Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra sportovních her Major League Soccer-historie a současnost Bakalářská práce Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Pavel Vacenovský Zdeněk Bezděk TVS/Trenérství Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brně dne 24. května 2013 podpis Děkuji vedoucímu bakalářské práce Mgr. Pavlu Vacenovskému, za podnětné rady, metodické vedení a připomínky k této práci. Úvod ........................................................................................................................ 6 1. FOTBAL V USA PŘED VZNIKEM MLS .................................................. 8 2. PŘÍPRAVA NA ÚVODNÍ SEZÓNU MLS ............................................... 11 2.1. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 17. října 1995..................................... 12 2.2. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 18. října 1995..................................... 14 2.3. První sponzoři MLS ............................................................................... 15 2.4. Platy Marquee players ............................................................................ 15 2.5. Další události v roce 1995 ...................................................................... 15 2.6. Drafty MLS ............................................................................................ 16 2.6.1. 1996 MLS College Draft ................................................................. 17 2.6.2. 1996 MLS Supplemental Draft ...................................................... -

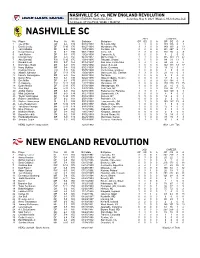

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

1985 NSCAA New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Cedarville College

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Men's Soccer Programs Men's Soccer Fall 1985 1985 NSCAA New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ mens_soccer_programs Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons This Program is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Men's Soccer Programs by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1985 NSCAA/New Balance All-America Awards Banquet National Soccer Coaches Association of America Saturday, January 18, 1986 Sheraton - St. Louis Hotel St. Louis, Missouri Dear All-America Performer, Congratulations on being selected as a recipient of the National Soccer Coaches Association of America/New Balance All-America Award for 1985. Your selection as one of the top performers in the Gnited States is a tribute to your hard work, sportsmanship and dedication to the sport of soccer. All of us at New Balance are proud to be associated with the All-America Awards and look forward to presenting each of you with a separate award for your accomplishment. Good luck in your future endeavors and enjoy your stay in St. Louis. Sincerely, James S. Davis President new balance8 EXCLUSIVE SPONSOR OF THE NSCAA/NEW BALANCE ALL-AMERICA AWARDS Program NSCAA/New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Master of Cerem onies............................. William T. Holleman, Second Vice-President, NSCAA The Lovett School, Georgia Invocation.................................... ....................................................................... Whitney Burnham Dartmouth College NSCAA All-America Awards Youth Girl’s and Boy’s T ea m s............................................................................. -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

THE CHRONICLE Manufacturer

MORE ACC SOCCER COVERAGE, PAGE 13 THURSDAYTH. NOVEMBER 5. 1987-i! E CHRONICLE DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 83, NO. 48 State match to Study indicates open first ACC sweetener not a soccer tourney headache cause By JOHN SENFT fWLJf By CHRIS SCHMALZER As the inaugural Atlantic Coast Con A study conducted at Duke Univer ference Soccer Tournament opens today, sity Medical Center and funded by the it promises to be more than a simple National Institute of Health and the showcase of some of the premier talent in manufacturer of Nutrasweet has con the country. Instead, for most of the cluded that the artificial sweetener is teams, it may turn into a war for survival. not likely to cause headaches in the The winner of the tournament receives general population. an automatic bid for the postseason The findings of the study, which NCAA Tournament. Traditionally, the began in October 1986 and involved 40 NCAA awards between two to five bids for volunteer subjects, were announced at every region, and in the strong South a press conference at the Medical region the competition for bids is fierce. Center Wednesday. The results will Third-ranked South Carolina appears to appear in today's issue of the New be a virtual certainty for one, and Duke England Journal of Medicine. has an inside track on a second. But "This study answers the question of North Carolina, Clemson, N.C. State and headaches" in relation to aspartame, Wake Forest are all sitting on the fence the generic name for Nutrasweet, said —a first-round loss will probably' mean Susan Schiffman, a professor of medi the end of their season. -

Division I Men's Soccer Records

DIVISION I MEN’S SOCCER RECORDS Individual Records 2 Individual Leaders 3 Annual Individual Champions 10 Team Records 12 Team Leaders 14 2017 Most-Improved Teams 20 Annual Team Champions 21 Final Coaches’ Polls 23 Final Soccer America Polls 28 Division I Winningest Teams 32 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Official NCAA Division I men’s soccer records Career (Minimum 45 Goals) Career (Minimum 2,500 Minutes) began with the 1959 season and are based on 2.31—Herb Schmidt, Rutgers, 1959-61 (90 in 0.34—Tony Meola, Virginia, 1988-89 (11 GA in information submitted to the NCAA statistics ser- 39 games) 2,922 min.) vice by institutions participating in the statistics rankings. Career records of players include only Assists Solo Shutouts those years in which they competed in Division Game Season I. Annual champions started in the 1998 season, 7—Mike Granelli, Saint Peter’s vs. NYU, Oct. 18—John Putna, Indiana, 1979; David Meves, which was the first year the NCAA compiled 17, 1985 Akron, 2009 (25 games played); Trey Muse, weekly leaders. In statistical rankings, the round- Season Indiana, 2017 (25 games played) ing of percentages and/or averages may indicate 24—Ben Ferry, George Washington, 1997 (18 Career ties where none exists. In these cases, the numeri- games) 55—David Meves, Akron, 2009-12 cal order of the rankings is accurate. Must have Career completed career to be ranked in per game career 66—Dante Washington, Radford, 1988-92 (88 Goalkeeper Minutes categories. games) Played Assists Per Game Career Season 8,608—David Meves, Akron, 2009-12 SCORING 1.64—Joe Casucci, Niagara, 1970 (23 in 14 games) Points Career (Minimum 30 Assists) 0.95—Hayden Knight, Marquette, 1976-79 (42 MISCELLANEOUS Game in 44 games) 18—Jim McMillan, Cleveland St. -

Nick Sakiewicz

Nick Sakiewicz A native of Passaic, New Jersey, Nick Sakiewicz (pronounced Suh‐kev‐itch) grew up playing on pitches and playgrounds of that North Jersey working‐class town. A first generation American, he acquired his soccer education playing in the diverse ethnic clubs throughout the northeast. Now, 17 years after joining Major League Soccer as a founding executive, Sakiewicz is the CEO & Operating Partner of Keystone Sports and Entertainment LLC. It is his insight, passion and expertise that founded Keystone, Philadelphia Union and created the environment that enabled the club to build Philadelphia Union’s home, PPL Park ‐ a picturesque, soccer‐specific stadium, on the banks of the Delaware River in Chester, Pennsylvania. Sakiewicz brought a team to a region passionate for soccer. In the playoff run in just its second year, a tone is set by Sakiewicz with all involved with Philadelphia Union of inclusiveness, passion and authenticity. Building an international reputation, Philadelphia Union has played against world‐ powerhouses such as Manchester United and Real Madrid. Key partners in the first two years, include stadium‐naming rights partner PPL Energy Plus and jersey sponsor Bimbo Bakeries, USA. Filled to near‐ capacity crowds each game, PPL Park has been recognized for numerous awards including Best of Main Line Today and ACE Project of the Year. Rounding out 2011, Philadelphia Union was named Delco Sports Figure of the Year by The Delaware County Daily Times. Prior to helping to create Keystone Sports and Entertainment LLC, Sakiewicz enjoyed a diverse and successful business career, in manufacturing, retail, real estate and financial services, in addition to sports management. -

Ews: June 22, 1998 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep June 1998 6-22-1998 Daily Eastern News: June 22, 1998 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1998_jun Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: June 22, 1998" (1998). June. 5. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1998_jun/5 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1998 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in June by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Big shoes ID Ron Papp retires as Associate Athletic Florida Director after 35 MONDAY Eastern IHinois University Charleston, Ill. 61920 years at burning June 22, 1998 Vol. 83, No. 155 Eastern Wildfires continue to spread 8 pages throughout the state ews PAGE PAGE3 ''Tell the truth and don't be afraid" 8 Edgar: a political life requires drive and determination By Matt Adrian society are well-prepared for the F.ditor-inChief opportunities, challenges and Gov. Jim Edgar spoke for the second responsibilities that many women of past time ar F.astem in two weeks. This time in generations , I think, could of handled but person and not beamed via satellite to lhe unfortunately were not given the campus. opportunity," Edgar said. "Girls State will Edgar was unable to make a speech in help (a girl) prepare for that" person at the Boys State convention two Illinois Girls State teaches students weeks ago because of heart problems. about the election and political process. In an address to 549 Girls State During lhe week, the high school juniors participants, Edgar talked about what it receive lecturei. -

M E N 'S Aw a Rd Wi N N E

Me n ’ s Awa r d Win n e r s Division I First-Team All-America (191 0 - 9 9 ) .. 64 Division I First-Team All-America by School.. 68 Division II First-Team All-America (198 1 - 9 9 ) .. 72 Division II First-Team All-America by School.. 72 Division III First-Team All-America (1 9 8 1 - 9 9 ) .. 73 Division III First-Team All-America by School.. 74 National Awa r d Win n e r s .. 75 64 DIVISION I FIRST-TEAM ALL-AMERICA D–Henry Francke, Harvard F–John Jewett, Princeton 19 2 8 Al l - A m e r i c a D–Francis Grant, Harvard F–Francis Righter, Cornell G–Ruddy, Yale D–Shepard, Yale F–J. Moulton Thomas, Princeton Tea m s D–Webster, Pennsylvania F–C. J. Woodridge, Princeton D–Henry Coles, Swarthmore F–Bell, Pennsylvania D–William Frazier, Haverford D–Howard Johnson, Swarthmore NOTE: The all-America teams were select- F–Shanholt, Columbia 19 2 2 F–Samuel Stokes, Haverford D–William Lingelbach, Pennsylvania ed by the various team captains of the G–J. Crossan Cooper, Princeton F–Tripp, Yale D–H. Bradley Sexton, Princeton Intercollegiate Association Football D–Amelia, Pennsylvania F–Walter Weld, Harvard F–Depler Bullard, Lehigh League for the 1909-10 season. Various D–Beard, Pennsylvania F–Dick Marshall, Penn St. team managers selected the team from the 19 1 4 D–John Smart, Princeton F–George Olditch, Cornell 1910-11 season until 1917. No teams D–John Sullivan, Harvard F–Henry Rudy, Swarthmore were selected in 1918 or 1919 due to G–Hopkins, Pennsylvania D–Elliot Thompson, Cornell F–Smith, Yale World War I. -

Goal Player” Fall 2014

WSA: Introducing “The Goal Player” Fall 2014 At the last World Cup we have all been able to enjoy the German goalkeeper Manuel Neuer who without a doubt showed that the position of the goalkeeper and his role on the team has changed dramatically over the last 10-20 years. This is of course due to the rule change in 1994 which made it no longer possible for goalkeepers to pick up a pass back from one of their team mates. This rule change, however was made 20 years ago, and is not the only reason why the role oF the goalkeeper has changed so much over the last several years. More teams nowadays focus on a well-developed build up from the back, teams push many players Forward to keep the opponents under pressure and the defensive line often plays very high up the pitch. To stay connected with the rest oF the team the goalkeeper is now required to step up away from its backline and serve as the last defender or the sweeper keeper. More than 70% of the work goalkeepers do nowadays is done with their feet and not with their hands! Due to all of these changes the role oF the goalkeeper has changed and the goalkeeper is now not only a keeper, but a field player that is able to his or her hands. Although worldwide many goalkeepers have become “goal players” many young goalkeepers in the US are not instructed or trained to include themselves when their team has the ball. This might be because many of the best soccer players the US produced over the years were great goalkeepers (Tony Meola, Brad Friedel, Kasey Keller and Tim Howard) who controlled the 6th yard boX. -

2002 NCAA Soccer Records Book

Men’s Award Winners Division I First-Team All-America (1910-2001).......... 68 Division I First-Team All-America by School......... 72 Division II First-Team All-America (1981-2001) ......... 76 Division II First-Team All-America by School........ 76 Division III First-Team All-America (1981-2001) ........ 77 Division III First-Team All-America by School....... 78 National Award Winners ................................... 80 68 ALL-AMERICA TEAMS—DIVISION I FIRST-TEAM ALL-AMERICA D–Henry Francke, Harvard F–John Jewett, Princeton 1928 All-America D–Francis Grant, Harvard F–Francis Righter, Cornell G–Ruddy, Yale D–Shepard, Yale F–J. Moulton Thomas, Princeton D–Henry Coles, Swarthmore Teams D–Webster, Pennsylvania F–C. J. Woodridge, Princeton F–Bell, Pennsylvania D–William Frazier, Haverford D–Howard Johnson, Swarthmore NOTE: The all-America teams were select- F–Shanholt, Columbia 1922 F–Samuel Stokes, Haverford D–William Lingelbach, Pennsylvania ed by the various team captains of the G–J. Crossan Cooper, Princeton F–Tripp, Yale D–H. Bradley Sexton, Princeton Intercollegiate Association Football D–Amelia, Pennsylvania F–Walter Weld, Harvard F–Depler Bullard, Lehigh League for the 1909-10 season. Various D–Beard, Pennsylvania F–Dick Marshall, Penn St. team managers selected the team from the 1914 D–John Smart, Princeton F–George Olditch, Cornell 1910-11 season until 1917. No teams D–John Sullivan, Harvard F–Henry Rudy, Swarthmore were selected in 1918 or 1919 due to G–Hopkins, Pennsylvania D–Elliot Thompson, Cornell F–Smith, Yale World War I. From 1926-40, the teams D–Clarence Dyer, Cornell F–Randolph Heizer, Harvard were selected by coaches from the D–Moore Gates, Princeton F–McElroy, Pennsylvania 1929 Intercollegiate Soccer Football Associa- D–Howard Lynch, Cornell F–Francis Righter, Cornell G–Bob McCune, Penn St.