On Vulnerability and Doubt on Vulnerability and Doubt Australian Centre for Contemporary Art 28 June—1 September 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIM SILVER Born 1974, Hobart EDUCATION 2004 Master of Fine Arts (Research), COFA, University of NSW, Sydney 1997 Bachelor of Vi

TIM SILVER Born 1974, Hobart EDUCATION 2004 Master of Fine Arts (Research), COFA, University of NSW, Sydney 1997 Bachelor of Visual Arts (Honours Class 1), Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney, Sydney GRANTS AND RESIDENCIES 2018 Woollahra Small Sculpture Prize (Winner) 2018 Australia Council for the Arts, New Work Grant 2016 Wynne Prize 2016, Art Gallery of NSW, Finalist 2016 Fleurieu Art Prize, Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, Finalist 2015 The Sovereign Asian Art Prize, Finalist 2015 Artspace Studio Residency, Sydney 2014 Australia Council New Work Grant 2008 Asialink Residency Grant, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2006 Australia Council New Work Grant 2004 Freedman Foundation Travelling Scholarship 2003 Australia Council New Work Grant 2002 Australian Post Graduate Award 2001 NSW Ministry for the Arts Touring Grant 2000 Artspace Studio Residency, Sydney 2000 Arts NSW Marketing Grant 2000 Pat Corrigan Artist Grant 1999 Arts NSW Marketing Grant 1999 Pat Corrigan Artist Grant 1998 Arts NSW Marketing Grant COLLECTIONS Artbank Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide Australia Council for the Arts Murray Art Museum, Albury Mint Museum, Charlotte, North Carolina Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney Ten Cubed Collection, Melbourne University of Queensland Art Museum Collection, Brisbane Woollahra Municipal Council Art Collection SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 The Distance Between Us, Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney 2016 You Promised Me Poems, Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney 2016 Oneirophrenia, Centre for Contemporary -

TRACY WILLIAMS Ltd. Simryn Gill

TRACY WILLIAMS Ltd. Simryn Gill Born 1959 Lives and works in Sydney, Australia and Port Dickson, Malaysia Solo Exhibitions 2017 Simryn Gill, Lunds konsthall, Lunds, Sweden 2016 Simryn Gill: relief, Utopia Art Sydney, Australia Simryn Gill: Sweet Chariot, Griffith University Art Gallery, Queensland, Australia Simryn Gill: The (Hemi)Cyclus of Leaves and Paper, Museum of Fine Arts Ghent, Belgium (cat.) 2015 Floating, three accounts, Tracy Williams, Ltd., New York, NY Simryn Gill: Like Leaves, Michael Janssen, Singapore Simryn Gill: Hugging The Shore, Centre For Contemporary Art (CCA), Singapore The Stormy Days, Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai, India 2014-15 Domino Theory, Espace Louis Vuitton München, Germany 2014 Blue, Tracy Williams, Ltd., New York, NY My Own Private Angkor, Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles, CA 2013 Here art grows on trees, Australian Pavilion, 55th Venice Biennale, curated by Catherine de Zegher (monograph) 2012 Full Moon, ANNAELLEGALLERY, Stockholm, Sweden (cat.) 2011 Inland, BREENSPACE, Sydney, Australia Simryn Gill: Gathering, CA2M - Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo, Móstoles Simryn Gill, McClelland Gallery + Sculpture Park, Langwarrin, VIC 2010 Holding Patterns, Tracy Williams, Ltd., New York, NY Letters Home, Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai, India (brochure) 2009 Interiors, Tracy Williams, Ltd., New York, NY Paper Boats, BREENSPACE, Sydney, Australia Simryn Gill: Inland, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, Australia. Toured to five regional Victorian venues in 2010 and 2011 (brochure) 2008 Simryn Gill: Gathering, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia. Toured to Anne and Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, Adelaide; Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane; Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne; Mackay City Gallery, Queensland, Australia (cat.) 2006 Run, Tracy Williams Ltd., New York, NY 32 Volumes, Maitland Regional Art Gallery, New South Wales; Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, Australia (brochure) Perspectives: Simryn Gill, Arthur M. -

The Alchemists

THE ALCHEMISTS Rediscovering Photography in the Age of the Jpeg /14 /16 /18 /20 /22 /24 /26 /28 /30 /32 /34 /36 /38 /40 /42 /44 /46 /48 /50 /52 /54 /56 /58 /60 /62 CONTENTS THE ALCHEMISTS 04 CURATORS 11 ARTISTS Joyce Campbell/14 Laura Moore/40 Ben Cauchi/16 Sarah Mosca/42 Danica Chappell/18 Anne Noble/44 Lisa Clunie/20 Sawit Prasertphan/46 Lucinda Eva-May/22 Kate Robertson/48 Ashleigh Garwood/24 Catherine Rogers/50 Mike Gray/26 Aaron Seeto/52 David Haines/28 Benjamin Stone-Herbert/54 Matt Higgins/30 CJ Taylor/56 Joyce Hinterding/32 Craig Tuffin/58 Benjamin Lichtenstein/34 James Tylor/60 Todd McMillan/36 Diasuke Yokota/62 Dane Mitchell/38 SYMPOSIUM 64 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 65 THE ALCHEMISTS It is often said that it was the painters who invented Photography (by bequeathing it their framing, the Albertian perspective, and the optic of the camera obscura). I say: no, it was the chemists. For the noeme “That-has-been” was possible only on the day when a scientific circumstance (the discovery that silver halogens were sensitive to light) made it possible to recover and print directly the luminous rays emitted by a variously lighted object. The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. ROLAND BARTHES¹ Photographs are both pictures of things and emanations from 05 things. Over the last twenty years all the buzz has been on the ‘picturing’ side of photography: we are astounded by the latest estimate of the astronomical number of smartphone images uploaded to the internet every second, we are shocked by the latest sickening images tweeted from a violent war zone, we are awed by the majestic detail in the latest mural photograph mounted behind pristine acrylic in an art museum, and we are habituated to the sleek look of digital images — either Photoshopped into high-dynamic-range conformity or with one selection from a convenient menu of retro Instagram- filters laid on top. -

Art Gallery of New South Wales Annual Report 2005 Art Gallery of New South Wales General Information

ART GALLERY ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES NSW Art Gallery Road The Domain Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: (02) 9225 1700 Information Line: (02) 9925 1790 Email (general): [email protected] For information on current exhibitions and events, visit the Gallery’s website www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL REPORT 2005 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES GENERAL INFORMATION ACCESS RESEARCH LIBRARY AND GALLERY SHOP PUBLIC TRANSPORT The Gallery opens every day except ARCHIVE Open daily from 10am to 5pm and until Buses: the 441 bus route stops at the ‘I have been in many museums around the world. You have a Easter Friday and Christmas Day The Gallery’s Research Library and 8.45pm each Wednesday night, the Gallery en route to the Queen Victoria between the hours of 10am and 5pm. Archive is open Monday to Friday Gallery Shop offers the finest range of art Building. The service runs every 20 national treasure here. Very impressive.’ Gallery visitor, 27 Feb 05 The Gallery opens late each Wednesday between 10am and 4pm (excluding books in Australia and also specialises in minutes on weekdays and every 30 night until 9pm. General admission is public holidays) and until 8.45pm each school and library supply. The shop minutes on weekends. Call the STA on free. Entry fees may apply to a limited Wednesday night. The Library is located stocks an extensive range of art posters, 131 500 or visit www.131500.info for number of major temporary exhibitions. on ground floor level and has the most cards, replicas and giftware. -

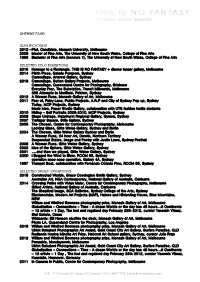

Cherine Fahd Qualifications 2012

CHERINE FAHD QUALIFICATIONS 2012 – Phd. Candidate, Monash University, Melbourne 2003 Master of Fine Arts, The University of New South Wales, College of Fine Arts 1996 Bachelor of Fine Arts (honours 1), The University of New South Wales, College of Fine Arts SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 Homage to a Rectangle, THIS IS NO FANTASY + dianne tanzer gallery, Melbourne 2014 Plinth Piece, Galerie Pompom, Sydney Camouflage, Artereal Gallery, Sydney 2013 Camouflage, Sutton Gallery Projects, Melbourne Camouflage, Queensland Centre for Photography, Brisbane Everyday Fear, The Substation, Transit billboards, Melbourne 365 Attempts to Meditate, Peloton, Sydney 2012 A Woman Runs, Monash Gallery of Art, Melbourne 2011 Fear of, Foley Lane, Public Projects, A.R.P and City of Sydney Pop up, Sydney Today, MOP Projects, Sydney Made Men, Fraser Studio Gallery, collaboration with UTS fashion textile students 2010 Hiding – Self Portraits 2009-2010, MOP Projects, Sydney 2008 Stage Unstage, Hazelhurst Regional Gallery, Gymea, Sydney 2007 Trafalgar Square, Stills Gallery, Sydney 2005 The Chosen, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne Looking Glass, Gitte Weise Gallery, Sydney and Berlin 2004 The Chosen, Gitte Weise Gallery Sydney and Berlin A Woman Runs, 24 hour Art, Darwin, Northern Territory Suspended States, Image and Poetry with Justin Lowe, Sydney Festival 2003 A Woman Runs, Gitte Weise Gallery, Sydney 2002 Idea of the Sphere, Gitte Weise Gallery, Sydney 2001 .…and then we played, Gitte Weise Gallery, Sydney 2000 I Begged the Wind to Blow, ROOM 35, -

The National 2019 New Australian Art

The National 2019 New Australian Art Art Gallery of New South Wales 29 March – 21 July 2019 Carriageworks 29 March – 23 June 2019 Museum of Contemporary Art Australia 29 March – 23 June 2019 The National 2019 www.the-national.com.au New Australian Art #nationalau EXHIBITING ARTISTS REVEALED FOR The National 2019: New Australian Art Image: Eugenia Lim, The Australian [Sydney, 20 August 2018] The Art Gallery of New South Wales Ugliness (still) 2018, multi-channel high-definition video installation, (AGNSW), Carriageworks and the Museum of Contemporary Art colour, sound. Image courtesy and © artist. Photograph: Tom Ross Australia (MCA) today announced that The National 2019: New Australian Art will present the work of 65 emerging, mid-career and established Australian contemporary artists living across the country and abroad. A major collaborative venture, The National 2019 is the second edition of a six-year initiative presented in 2017, 2019 and 2021, exploring the latest ideas and forms in contemporary Australian art. Connecting three of Sydney’s key cultural precincts – The Domain, Redfern and Circular Quay – The National 2019 follows a successful first edition of the exhibition held in autumn of 2017 that attracted 286,631 visitors. The National 2019 www.the-national.com.au New Australian Art #nationalau The 2019 exhibition is curated by AGNSW Curator of Photographs, Isobel Parker Philip; Left to right: Tom Mùller, installation view Carriageworks Senior Curator of Visual Arts, Daniel Mudie Cunningham; and MCA Curator of Floating Castle, 2017, fog machines, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collections and Exhibitions, Clothilde Bullen with MCA 23 x 30m, Montegemoli, Italy. -

Kylie Banyard

NICHOLAS THOMPSON GALLERY KYLIE BANYARD EDUCATION 2014 Doctor of Philosophy (Fine Arts) Imagining Alternatives: Gazing at the contemporary world through figurations of the outmoded Supervisors: Senior Lecturer Dr. Toni Ross and Dr. Noelene Lucas University of New South Wales (faculty of Art & Design) 2007 Master of Fine Arts Supervisor: Senior Lecturer Gary Carsley University of New South Wales (faculty of Art & Design) 2001 Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) University of New South Wales (faculty of Art & Design) 1995 Associate Diploma of Fine Arts Major: Photography, Minor: Painting West Wollongong TAFE SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Holding Ground, Nicholas Thompson Gallery, Melbourne 2019 Blue Ridge Moon, Galerie pompom, Sydney 2018 The Improbable Outside, Nicholas Thompson Gallery, Melbourne 2017 The Hereafter, Galerie pompom, Sydney 2014 Mono Nuovo, Galerie pompom, Sydney Imagining Alternatives, Broken Hill Regional Gallery, Broken Hill 2013 Imagining Alternatives, Firstdraft Gallery, Sydney 2012 Dwelling, Galerie pompom, Sydney 2011 Staged Alternatives, GRANTPIRRIE, Sydney 2009 Take Me to Magic Mountain, MOP Projects, Sydney 2008 Phantom in the Corner, Ivan Dougherty Gallery, Sydney 155 LANGRIDGE ST. COLLINGWOOD VIC. +61 3 9415 7882 nicholasthompsongallery.com.au NICHOLAS THOMPSON GALLERY COLLABORATIVE (TWO PERSON) EXHIBITIONS 2016 Something immeasurably better, Bus Projects, Melbourne, with Deb Mansfield 2014 BANYARD AND ADAMS, Fleet, curated by OH YEAH COOL GREAT, Metro Arts, Brisbane 2013 Anonymous Séance and the Domes of Silence, BANYARD -

Kylie Banyard

NICHOLAS THOMPSON GALLERY KYLIE BANYARD EDUCATION 2014 Doctor of Philosophy (Fine Arts) Imagining Alternatives: Gazing at the contemporary world through figurations of the outmoded Supervisors: Senior Lecturer Dr. Toni Ross and Dr. Noelene Lucas University of New South Wales (faculty of Art & Design) 2007 Master of Fine Arts Supervisor: Senior Lecturer Gary Carsley University of New South Wales (faculty of Art & Design) 2001 Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) University of New South Wales (faculty of Art & Design) 1995 Associate Diploma of Fine Arts Major: Photography, Minor: Painting West Wollongong TAFE SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 The Improbable Outside, Nicholas Thompson Gallery, Melbourne 2017 The Hereafter, Galerie pompom, Sydney 2014 Mono Nuovo, Galerie pompom, Sydney Imagining Alternatives, Broken Hill Regional Gallery, Broken Hill 2013 Imagining Alternatives, Firstdraft Gallery, Sydney 2012 Dwelling, Galerie pompom, Sydney 2011 Staged Alternatives, GRANTPIRRIE, Sydney 2009 Take Me to Magic Mountain, MOP Projects, Sydney 2008 Phantom in the Corner, Ivan Dougherty Gallery, Sydney COLLABORATIVE (TWO PERSON) EXHIBITIONS 2016 Something immeasurably better, Bus Projects, Melbourne, with Deb Mansfield 2014 BANYARD AND ADAMS, Fleet, curated by OH YEAH COOL GREAT, Metro Arts, Brisbane 155 LANGRIDGE ST. COLLINGWOOD VIC. +61 3 9415 7882 nicholasthompsongallery.com.au NICHOLAS THOMPSON GALLERY 2013 Anonymous Séance and the Domes of Silence, BANYARD AND ADAMS (collaboration with Ron Adams), ALASKA Projects, Sydney SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2017 Art -

The National 2019 New Australian Art

The National 2019 New Australian Art Art Gallery of New South Wales 29 March – 21 July 2019 Carriageworks 29 March – 23 June 2019 Museum of Contemporary Art Australia 29 March – 23 June 2019 www.the-national.com.au The National 2019 #nationalau New Australian Art The National 2019: New Australian Art opens with 70 Australian contemporary artists at three of Sydney’s leading cultural institutions Image: Tony Albert, House of Discards, The National 2019: New Australian Art was today unveiled in Sydney, The National 2019, Carriageworks. Image representing the second biennial exhibition in a six-year partnership Zan Wimberley. between the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Carriageworks and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA) that will continue until 2021. The National 2019: New Australian Art is a celebration of contemporary Australian art, showcasing work being made across the country and abroad by artists of different generations and cultural backgrounds. Through ambitious new and commissioned projects, the 70 artists and collectives featured across the three venues respond to the times in which they live, presenting observations that are provocative, political and poetic. The National 2019 www.the-national.com.au New Australian Art #nationalau The exhibition profiles the diversity of Australian contemporary art practice. Over 60 per cent of Left to right: Daisy Japulija, Sonia Kurarra, the exhibiting artists are women and over a third are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists. Tjigila Nada Rawlins, Ms Uhl, installation view, The National Encompassing performance, site-responsive installation, painting, film and photography The 2019: New Australian Art, National 2019: New Australian Art presents a dynamic cross-section of Australian art. -

Annual Report 2013–14

2013–14 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2013–14 ANNUAL REPORT 2013–14 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Tom Roberts Act 1975. Miss Minna Simpson 1886 oil on canvas The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is to be 59.5 x 49.5 cm an inspiration for the people of Australia. Purchased with funds donated by the National Gallery of Australia Council and Foundation in honour of Ron Radford AM, Director The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National of the National Gallery of Australia (2004–14), 2014. 100 Works for Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, 100 Years corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. (back cover) Polonnaruva period (11th–13th century) In 2013–14, the National Gallery of Australia received Sri Lanka appropriations from the Australian Government Standing Buddha 12th century totalling $49.615 million (including an equity injection bronze of $16.453 million for development of the national 50 x 20 x 20 cm art collection), raised $29.709 million, and employed Geoffrey White OAM and Sally White OAM Fund, 2013. 100 Works 257.93 full-time equivalent staff. for 100 Years © National Gallery of Australia 2014 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Cherine Fahd Available Works 2017

CHERINE FAHD AVAILABLE WORKS 2017 ARTEREAL GALLERY 747 DARLING ST ROZELLE NSW 2039 +61 (2) 9818 7473 [email protected] WWW.ARTEREAL.COM.AU Camouflage (eye closed) 2013 lambda print edition of 5 + 2 AP 50.8 x 42.8cm $2,800 unframed Cherine Fahd’s Camouflage series of photographic self images runs counter to trend in this age of narcissism when the cult of the ‘selfie’ is rampant and its forms of digitally generated self portrait, typically taken with a handheld smartphone, are destined for upload and maximum dissemination via social media networks. In a game of disguise, of ‘now you see me - now you don’t’ in her recent Camouflage works, Cherine Fahd seeks to conceal as much as she reveals of the self in a continuation of her quest since 2006 to test ideas of disclosure in portraiture. Cherine Fahd subverts the convention of photo portraiture where the face and body are the focus. In Camouflage they are mostly hidden; concealed behind geometric planes of intense solid colours which allude to the style and visual language of painting and hard edge abstraction. The coloured expanses are interrupted with only the minimal protrusion of a part. Cherine Fahd’s earliest encounter with being photographed was posing for a studio portrait with her sister at the age of four. The artist experienced an intense sense of disappointment when the image did not accord with her own internal sense of self. Since 2006 she has made self portraits in which she hides her face to complicate the depiction and interpretation and to test ideas central to portraiture that encompass staging and performance in the face of the camera, the interplay between everyday reality and the reconstruction of that reality through photography. -

Artspace Sydney

ARTSPACE Annual Report 2017 Prepared by Artspace P.1 Artspace Artspace TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION EVER CHANGING, EVER CHALLENGING, Artspace is Executive Report 4 where audiences encounter the artists and the ideas of our times. 2017 Highlights 9 Expanded Artistic Program MISSION Exhibitions 12 Artspace is Australia’s leading interdisciplinary Ideas Platform 29 space for the production and presentation Studios 43 of contemporary art. Through exhibitions, Public Programs 60 International Visiting Curators Program 65 performances, artist residencies, and public International Partnerships & Commissioned Work 69 programs, Artspace is where artists of all National & Regional Touring 73 generations test new ideas and shape public Performance Against Goals conversation. Committed to experimentation, Expanded Artistic Program 76 collaboration and advocacy, Artspace’s mission Artists and Advocacy 78 is to enhance our culture through a deeper New Works in Development 80 Commisioning Series 82 engagement with contemporary art. Publishing 84 Audience Growth, Engagement and Reach 86 ABOUT US Organisational Dynamism and Sustainability 96 Artspace is an independent contemporary art space that receives government support for its Key Performance Indicators 104 activities from the federal government through Artspace Directors and Staff 106 the Australia Council for the Arts and the state Artspace Partners and Supporters 108 government through Create NSW. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We show our respect and acknowledge the traditional owners of the land, the Gadigal people