Final Report October 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urgent Appeal to the United Nations Special Procedures on the Denial of Access to Healthcare for Palestinian Patients from the Gaza Strip

Joint Urgent Appeal to the United Nations Special Procedures on the Denial of Access to Healthcare for Palestinian Patients from the Gaza Strip Date: 26 June 2020 Submitted by: Al-Haq, Law in the Service of Man Palestinian Centre for Human Rights Al Mezan Centre for Human Rights Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies For the attention of: − The Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967, Mr S. Michael Lynk; − The Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Mr Dainius Pūras; − The Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or Punishment, Mr Nils Melzer; and − The Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, Ms E. Tendayi Achiume. 1. Overview June 2020 marks 13 years since the start of Israel’s illegal closure of the occupied Gaza Strip.1 The closure, which amounts to unlawful collective punishment over two million Palestinians, has undermined all aspects of life in Gaza and deprives the Palestinian people of the enjoyment of the full spectrum of their inalienable rights, comprising their right to self-determination, including the right of 1 Recent materials on the Gaza closure were compiled by Al-Haq, Al Mezan Centre for Human Rights, the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights (PCHR), and Medical Aid for Palestinians in a blog that marks 13 years of illegal Israeli closure. The blog, part of the Gaza2020 campaign, calls for the immediate lifting of the Gaza closure: https://medium.com/@lifttheclosure/its-2020-lift-the-gaza-closure-c3f586611c11. -

Curriculum Vitae Jumana Hassan Odeh, Md, Mph

CURRICULUM VITAE JUMANA HASSAN ODEH, MD, MPH Address: Jerusalem, P.O. Box 54963 Telephone: 00972- 546 227 887 or 00970-59 318 398 Fax: 009702 – 2964482 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Nationality: Palestinian & American Key Qualifications: Doctor of Medicine and Master in Community Health in Developing Countries. I have more than 25 years experience in the public health sector, community paediatrics, child development and disability, with emphasis in policy-related development issues, particularly in the areas of participatory development, health and education. Profession: Founder and Director General for Palestinian Happy Child Center, Jerusalem Faculty Director, FXB Disability Rights Program, François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Harvard University Child Health Advisor – Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health- UK International Experts Evaluation team member for Shafallah Center for Children with Special Needs – Doha, Qatar DEGREES: 1981 Doctor in Medicine, Leningrad Pediatric Medical School. Leningrad, Former Soviet Union. 1988 Master in Community Health in Developing Countries, The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK. Medical Licenciature, Jordanian Medical Association, Amman and Palestinian Medical Association, Jerusalem Other related courses: 1990-2012 Autism Diagnostic and Observation Schedule (ADOS), Tavistock Centre, London, UK. Epileptology, Oxford School of Medicine, Oxford UK. 1 Behaviour Change and Communication, “BCC” New York and Cairo Universities, Cairo, Egypt. Advanced and Basic Cardiac Life Support-Provider and Instructor, American Heart Association, Jerusalem Medical Ethics, Leadership Project, Utrecht Univesity, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Health and Human Rights Leadership Course, International Federation for Health and Human Rights “IFHHRO”, Durban and Cape Town, South Africa. -

East Jerusalem

AL-HAQ COVID-19 AND THE SYSTEMATIC NEGLECT OF PALESTINIANS IN EAST JERUSALEM JOINT BRIEFING PAPER Al-Haq, Jerusalem Legal Aid and Human Rights Center (JLAC), and Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP) July 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 East Jerusalem before COVID-19: Prolonged occupation, annexation, and impunity .................................... 4 East Jerusalem during COVID-19: Between systematic neglect and healthcare de-development ............ 6 Lack of testing facilities ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Inaccurate and unreliable data to track the spread of COVID-19 ............................................................................................................................. 7 Harassment, arrests, and persecution of Palestinian health activists ................................................................................................................. 8 Palestinian hospitals at breaking point .................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 COVID-19 meets Israeli bureaucracy, prolonged occupation, and militarism .................................................................................................... -

MEDICAL CARE UNDER SIEGE Israel’S Systematic Violation of Gaza’S Patient Rights

Al Mezan Center For Human Rights MEDICAL CARE UNDER SIEGE Israel’s Systematic Violation of Gaza’s Patient Rights Gaza February 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 3 CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................. 5 PUBLIC HEALTH: ELECTRICITY, WATER AND SANITATION .............................................................. 5 AVAILABILITY & ACCESSIBILITY: LEAVING GAZA FOR MEDICAL TREATMENT ............................... 5 BRINGING GOODS AND SERVICES INTO GAZA ................................................................................ 6 LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND PRACTICE ........................................................................................................ 7 INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW ........................................................................................... 7 INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW............................................................................................ 8 SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................ 10 MEDICAL REFERRALS IN PRACTICE ......................................................................................................... 10 REFERRAL CRITERIA AND PROCESS ............................................................................................... -

Patients in the Gaza Strip Unable to Obtain Israeli-Issued Permits to Access the Healthcare

WHO EMRO | Patients in the Gaza Strip unable to obtain Israeli-issued permits to access the healthcare Following suspension of permit processing and coordination, Palestinian patients face additional difficulties to accessing healthcare. Before March, there were more than 1,750 permit applications each month for Gaza patients and more than 7,000 permit applications each month for West Bank patients, though this number reduced drastically during the COVID-19 outbreak. Patients need permits to reach health services in different parts of the occupied Palestinian territory, with the majority needing access to East Jerusalem. Almost a third of applications are for cancer patients; others require specialized surgeries, diagnostic imaging, cardiology, or other services otherwise unavailable. Overall, this group of patients is very sick, with their probability of survival at six months from first permit application less than 90%. Waseem is 25 years old and has a congenital heart problem. He is from Beit Lahia in the north of Gaza Strip. 21 June 2020 1 / 7 WHO EMRO | Patients in the Gaza Strip unable to obtain Israeli-issued permits to access the healthcare Waseem was born with a congenital heart problem that involved the narrowing of one of his heart valves. When he was a child, he underwent treatments including a procedure to dilate the valve and open-heart surgery. The surgery was effective at that time, and Waseem finished school and went onto graduate from Al-Azhar University in business administration in 2018. In March 2018, however, Waseem noticed general tiredness and had difficulty breathing. Investigations at Shifa Hospital revealed that the same heart valve was not working properly. -

The Case of Birth in Palestine

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by FADA - Birzeit University Cult Med Psychiatry (2008) 32:328–357 DOI 10.1007/s11013-008-9098-y ORIGINAL PAPER Building the Infrastructure, Modeling the Nation: The Case of Birth in Palestine Livia Wick Published online: 17 June 2008 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract This article explores the intersection between the professional politics of medicine and national politics during the second Palestinian uprising, which erupted in 2000. Through an analysis of stories about childbirth from actors in the birth process—obstetricians, midwives and birth mothers—it examines two overlapping movements that contributed to building the public health infrastructure, the movement of sumud or steadfastness (1967–87) and the popular health movement (1978–94), as well as their contemporary afterlife. Finally, it deals with relations between medicine and governance through an analysis of the interpenetration of medical and political authority. The birth stories bring to light two contrasting visions of a nation in the context of restrictions on mobility and a ground chopped up by checkpoints. The quasi-postcolonial condition of Palestine as popular con- struct, institutional protostate organism, and the lived experience of its experts and of its gendered subjects underlie the ethnographic accounts. Keywords Public health Á Nation-building Á Palestine Á Childbirth Introduction This article is intended to clarify the relationship between health and nation- building in Palestine. Based primarily on interviews with professionals and participant observation in hospitals and clinics, it examines two overlapping movements that contributed to building the public health infrastructure in the occupied Palestinian territories, including the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the L. -

Monthly Reporting

REPORT 2021 February MONTHLY Health Access Barriers for patients in the occupied Palestinian territory 7,684 73% 88% 6 referrals issued to access of Gaza patient permit of West Bank patient permit Gaza patients called for health facilities outside the applications approved applications approved security interrogation. Palestinian MoH 1,634 Gaza 46% 83% of Gaza companion permit of West Bank companion permit 5,956 West Bank applications approved applications approved IN FOCUS Jana and palliative care in the Gaza Strip Address: 10 Abu Obaida Street, Sheikh Jarrah, Jerusalem Tel: +972-2-581-0193 | www.emro.who.int/countries/pse Ref: April 2021 Email: [email protected] (Published 19 April 2021) Part 1 Referrals February Referrals by the Ministry of Health In February, the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MoH) issued 7,684 referrals to health care services delivered by non-MoH providers. West Bank referrals comprised 78% (5,956) of all MoH referrals, including 696 referrals for patients from East Jerusalem, while the West Bank population comprises approximately 60% 1,634 of the population in the oPt. Gaza referrals accounted for 21% (1,634), while Gaza’s population comprises Gaza Strip approximately 40% of the population in the oPt. The origin of 92 (1%) of referrals was not reported and two patients were referred from Jordan. After an almost 40% reduction in West Bank referrals from March to April 2020, by June 2020 West Bank 5,956 West Bank referrals had recovered to the pre-COVID-19 level. In February, there were 5,956 referrals compared to a monthly average of 5,056 referrals for 2020. -

Crossing Barriers to Access Health in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, 2013 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Right to health Crossing barriers to access health in the occupied Palestinian territory, 2013 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data World Health Organization Right to health: crossing barriers to access health in the occupied Palestinian territory, 2013 / World Health Organization p. WHO-EM/OPT/05/E 1. Health Services Accessibility - Palestine 2. Delivery of Health Care 3. Patient Rights 4. Human Rights I. Title (NLM Classification: WA 300) Developed Countries Price: USD 20.00 Developing Countries Price: USD 14.00 World Health Organization 2014 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Al Mezan Center for Human Rights Is an Independent, Non-Partisan and Non- Governmental Human Rights Organization Established in 1999

In focus: The effects of Israel’s offensive and tightened blockade on Gaza’s patients and healthcare system – May 2021 Al Mezan Center for Human Rights is an independent, non-partisan and non- governmental human rights organization established in 1999. Al Mezan is dedicated to protecting and advancing the respect of human rights, with a focus on economic, social, and cultural rights, supporting victims of violations of international law through legal initiatives, and enhancing democracy, community and citizen participation, and respect for the rule of law in Gaza as part of occupied Palestine. Main office: 5/102-1 Al Mena, Omar El-Mukhtar Street Western Rimal Gaza City, Gaza Strip (occupied Palestine) P.O. Box 5270 Telfax: +970 (0)8 282-0442/7 Jabalia office: Al Eilah Building (1st Floor), Al Trans Square Jabalia Camp, Gaza Strip (occupied Palestine) P.O. Box: 2714 Telfax: +970 (0)8 248-4555/4 Rafah office: Qishta Building (1st Floor), Othman Bin Affan Street Rafah, Gaza Strip (occupied Palestine) Telfax: +970 (0)8 213-7120 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mezan.org/en For complaints or suggestions, please complete the e-form available on our website. © 2021 AL MEZAN CENTER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 1 In focus: The effects of Israel’s offensive and tightened blockade on Gaza’s patients and healthcare system – May 2021 Introduction May 2021 was one of the grimmest months in recent years for more than two million Palestinians in the occupied Gaza Strip. Between 10-21 May 2021, Gaza endured Israel's fifth large-scale military operation in the Strip since 2008. -

Monthly Reporting

REPORT 2019 July July MONTHLY Health Access Barriers for patients in the occupied Palestinian territory 10,676 71% 84% 7 referrals issued to Gaza and West of Gaza patient permit applications to of West Bank patient permit Gaza patient companions called Bank patients to access health Israeli authorities and applications and for security interview, facilities outside the Palestinian MoH delayed 3,612 Gaza 53% 78% 2 accepted of companions permit applications to of companions permit applications 6,396 West Bank exit via Erez approved approved 5 delayed IN FOCUS East Jerusalem hospitals a cornerstone of the Palestinian health system Address: 10 Abu Obaida Street, Sheikh Jarrah, Jerusalem Ref: Seven Tel: +972-2-581-0193 | www.emro.who.int/countries/pse Email: [email protected] (Published 16 September 2019) Part 1 Referrals July Referrals by the Ministry of Health 3,612 In July, the Palestinian Ministry of Health approved 10,676 referrals. 60% (6,396) of referrals were for Gaza West Bank patients, including 1,223 referrals for patients from Jerusalem, while 34% (3,612) of referrals were for Gaza patients. The origins for 665 referrals (6%) were not reported and three patients were 6,396 West Bank referred from Jordan. Referrals for female patients comprised 47% of the total. Reduced referrals to referrals approved for financial Israeli hospitals persisted, reflecting the Palestinian MoH’s decision in March. There were 121 referrals coverage for healthcare outside to Israeli hospitals from Gaza, 31% of the 2018 monthly average (389), and 433 referrals for West the Palestinian Ministry of Health Bank patients, 37% of the 2018 monthly average (1,185). -

The Case of Al-Makassed Hospital in Jerusalem

Surviving and Serving under Occupation: The case of Al-Makassed Hospital in Jerusalem A lecture and open discussion with Dr. Rafiq Husseini Director of Al-Makassed Hospital, Arab-East Jerusalem September 12, 2014 Summary by Bayan Jaber Serving in a Palestinian hospital under Israeli occupation comes with its perils and challenges. These very challenges were discussed by Dr. Rafiq Husseini in a lecture entitled “Surviving and Serving under Occupation: The case of Al-Makassed Hospital in Jerusalem”. Held at the Issam Fares Institute at the American University of Beirut (AUB), the event was co-organized with the Collaborative for Leadership and Innovation in Health Systems (CLI), and AUB’s Faculty of Health Sciences. Dr. Husseini discussed his experience with Al-Makassed Hospital in Jerusalem as a case study of discrimination, national duty, working towards sustainability under occupation, and as a symbol of Palestinian steadfastness and resistance in Jerusalem. He started by presenting the repressive measures Jerusalem faces today. He pointed out that streets are being renamed, Palestinians are being denied building permits and their Jerusalem IDs are being withdrawn. Dr. Husseini presented Al-Makassed Hospital as one that characterizes a unique case of national steadfastness. To begin with, the hospital is owned solely by Palestinian people. Overlooking Al- Aqsa/Dome of the rock, the hospital's geographic location is considered to be a very strategic one. In fact, it represents the best location for real estate which is why there is an Israeli proposal for the construction of a cable car system. Al-Makassed Hospital is the main pillar for the other five Jerusalem hospitals. -

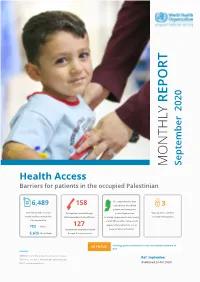

Monthly Report

REPORT 2020 September MONTHLY Health Access Barriers for patients in the occupied Palestinian No comprehensive data 6,489 158 available for West Bank 3 patient and companion referrals issued to access Gaza patients exited through permit applications Gaza patients called for health facilities outside the Beit Hanoun/Erez for healthcare following suspension to functioning security interrogation Palestinian MoH of Civil Affairs Office;985 permits approved for patients to access 783 Gaza 127 Gaza patient companions exited Augusta Victoria Hospital. 5,625 West Bank through Beit Hanoun/Erez IN FOCUS Oncology patient arrested en route to medical treatment at Erez Address: 10 Abu Obaida Street, Sheikh Jarrah, Jerusalem Ref: September Tel: +972-2-581-0193 | www.emro.who.int/countries/pse Email: [email protected] (Published 28 Oct 2020) Part 1 Referrals September Referrals by the Ministry of Health In September, the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MoH) issued 6,489 referrals to non-MoH facilities. A greater proportion of referrals were for patients from the West Bank despite the easing of obstacles to the coordination of permits with the implementation of a temporary coordination mechanism 783 through WHO from 6 September. West Bank referrals comprised 87% (5,625) of all MoH referrals (the Gaza Strip West Bank population comprises approximately 60% of the population in the oPt), including 1,082 for patients from Jerusalem, with Gaza referrals accounting for 12% (783). Meanwhile, one referral was for a Palestinian patient in Jordan and the origin of 80 referrals was not reported. 5,625 West Bank After an almost 40% reduction in West Bank referrals from March to April 2020, by June 2020 West Bank referrals had recovered to the pre-COVID-19 level.