Strategy for a Pest-Free Banks Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Tour of Christchurch New Zealand Aotearoa & Some of the Sights We

Welcome to a Tour of Christchurch New Zealand Aotearoa & some of the sights we would have liked to have shown you • A bit of history about the Chch FF Club and a welcome from President Jan Harrison New Zealand is a long flight from most large countries New Zealand is made up of two main islands and several very small islands How do we as a country work? • NZ is very multi cultural and has a population of just over 5 million • About 1.6 M in our largest city Auckland • Christchurch has just on 400,000 • Nationally we have a single tier Government with 120 members who are elected from areas as well as separate Maori representation. • Parliamentary system is based on a unitary state with a constitutional monarchy. How has Covid 19 affected us? • Because of being small islands and having a single tier Govt who acted very early and with strong measures Covid 19, whilst having had an impact on the economy, has been well contained • We are currently at level 1 where the disease is contained but we remain in a state of being prepared to put measurers in place quickly should there be any new community transmission. • There are no restrictions on gathering size and our sports events can have large crowds. • Our borders are closed to general visitor entry. • We are very blessed South Island Clubs Christchurch Christchurch Places we like to share with our visiting ambassadors First a little about Christchurch • Located on the east coast of the South Island, Christchurch, whose Maori name is Otautahi (the place of tautahi), is a city of contrasts. -

The Public Realm of Central Christchurch Narrative

THE PUBLIC REALM OF CENTRAL CHRISTCHURCH NARRATIVE Written by Debbie Tikao, Landscape Architect and General Manager of the Matapopore Charitable Trust. Kia atawhai ki te iwi – Care for the people Pita Te Hori, Upoko – Ngāi Tūāhuriri Rūnanga, 1861 The Public Realm of Central Christchurch Narrative 1 2 CERA Grand Narratives INTRODUCTION This historical narrative weaves together Ngāi Tahu cultural values, stories and traditional knowledge associated with Ōtautahi (Christchurch) and the highly mobile existence of hapū and whānau groups within the Canterbury area and the wider landscape of Te Waipounamu (South Island). The focus of this historical narrative therefore is on this mobile way of life and the depth of knowledge of the natural environment and natural phenomena that was needed to navigate the length and breadth of the diverse and extreme landscape of Te Waipounamu. The story that will unfold is not one of specific sites or specific areas, but rather a story of passage and the detailed cognitive maps that evolved over time through successive generations, which wove together spiritual, genealogical, historical and physical information that bound people to place and provided knowledge of landscape features, mahinga kai and resting places along the multitude of trails that established the basis for an economy based on trade and kinship. This knowledge system has been referred to in other places as an oral map or a memory map, which are both good descriptions; however, here it is referred to as a cognitive map in an attempt to capture the multiple layers of ordered and integrated information it contains. This historical narrative has been written to guide the design of the public realm of the Christchurch central business area, including the public spaces within the East and South frames. -

Bays Area Community Directory 2020

BAYS AREA COMMUNITY DIRECTORY 2020 1 | P a g e Proudly supported by Contents Welcome to the 2020 edition of the Bays Area Community Directory ............... 3 Emergency Information .............................................................................................. 4 Local Emergency Services ...................................................................................... 4 Community Response Teams.................................................................................. 5 Christchurch Hospital ............................................................................................... 5 After Hours Medical Care ........................................................................................ 5 Natural disasters ........................................................................................................ 5 Defibrillator Locations............................................................................................... 9 How to Stay Informed - Radio ............................................................................... 10 Notes about this directory ........................................................................................ 11 Key local organisations .......................................................................................... 11 Charitable Status .................................................................................................... 11 Public interest/good .............................................................................................. -

Coastal Water Quality in Selected Bays of Banks Peninsula 2001 - 2007

Coastal water quality in selected bays of Banks Peninsula 2001 - 2007 Report R08/52 ISBN 978-1-86937-848-6 Lesley Bolton-Ritchie June 2008 Report R08/52 ISBN 978-1-86937-848-6 58 Kilmore Street PO Box 345 Christchurch Phone (03) 365 3828 Fax (03) 365 3194 75 Church Street PO Box 550 Timaru Phone (03) 688 9069 Fax (03) 688 9067 Website: www.ecan.govt.nz Customer Services Phone 0800 324 636 Coastal water quality in selected bays of Banks Peninsula 2001 – 2007 Executive Summary This report presents and interprets water quality data collected by Environment Canterbury in selected bays of Banks Peninsula over two time periods: November 2001-June 2002 and July 2006-June 2007. Over 2001- 2002 the concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus based determinands (nutrients) were measured while over 2006-2007 the concentrations of nutrients, chlorophyll-a, total suspended solids, enterococci, and salinity were measured. The bays sampled were primarily selected to represent a range of geographic locations around the peninsula. These bays varied in regard to aspect of the entrance, length, width and land use. The bays sampled over both time periods were Pigeon Bay, Little Akaloa, Okains Bay, Le Bons Bay, Otanerito and Flea Bay. Hickory Bay and Te Oka Bay were also sampled over 2001-2002 but not over 2006-2007 while Port Levy and Tumbledown Bay were sampled over 2006-2007 but not over 2001-2002. Median concentrations of the nutrients ammonia nitrogen (NH3N), nitrate-nitrite nitrogen (NNN), total nitrogen (TN), dissolved reactive phosphorus (DRP) and total phosphorus (TP) were typically comparable to those reported from sites north and south of Banks Peninsula but some differed from those in Akaroa and Lyttelton harbours. -

A VISION for a PEST FREE BANKS PENINSULA / TE PĀTAKA O RĀKAIHAUTŪ in 2050 a Cacophony of Native Birdsong Resounds Across the Peninsula at Dawn and Dusk

PEST FREE BANKS PENINSULA BENEFITS OF PEST FREE BANKS PENINSULA/TE PĀTAKA O RĀKAIHAUTŪ The biodiversity gains in growing populations of Tūi, ruru (morepork), pīwakawaka (fantail), Kororā (white flippered little blue penguin), hoiho (yellow-eyed penguin), Tītī (sooty shearwater), jewelled geckos, spotted skinks, the Banks Peninsula tree Wētā and Akaroa daisies all contribute to creating a native taonga for the people of Ōtautahi / Christchurch, Canterbury and visitors to the area. Active pest management reduces or removes stressors from the ecological system, which in turn contributes to species being more resilient to other environmental stressors, increasing their chances of survival. WHAT YOU CAN DO to help ensure a Pest Free Banks Peninsula / Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū Visit our website to: • Make a donation • Volunteer your time, expertise or goods • Participate in neighbourhood trapping programmes • Find out about upcoming events A VISION FOR A PEST FREE BANKS PENINSULA / TE PĀTAKA O RĀKAIHAUTŪ In 2050 a cacophony of native birdsong resounds across the Peninsula at dawn and dusk. Indigenous plant and animal species thrive and Banks Peninsula, including the Port Hills and Kaitōrete, is a taonga www.pestfreebankspeninsula.org.nz enjoyed by the people of Ōtautahi/Christchurch, Canterbury, and visitors to the area. PEST FREE BANKS PENINSULA WHAT IS PEST FREE BANKS PENINSULA? THE VALUE OF BANKS PENINSULA / TE PĀTAKA O RĀKAIHAUTŪ Pest Free Banks Peninsula/Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū is a collaborative programme to protect Banks Peninsula / Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū is a unique place, rich with native flora and fauna. and enhance biodiversity on the Peninsula through the widespread eradication of animal pests. -

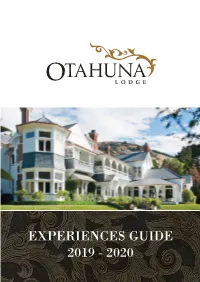

Experiences Guide 2019

EXPERIENCES GUIDE 2019 - 2020 WELCOME TO CANTERBURY! NEW ZEALAND’S LARGEST AND MOST DIVERSE CONTENTS PROVINCE BOASTS AN AMAZING ARRAY OF EXPERIENCES TO INCITE YOUR OWN PERSONAL LIFE AT OTAHUNA SENSE OF EXPLORATION. P.5) COOKING CLASS P.5) GARDEN TOUR P.6) RELAXATION P.6) PICNIC LUNCH P.7) WALKING & BIKING LIFE BEYOND OTAHUNA P.8) AKAROA & BANKS PENINSULA P.9) BANKS PENINSULA FARM TOUR AND E-BIKE EXPLORER P.10) GRAND GARDENS P.11) TRANZALPINE ADVENTURE P.12) CHRISTCHURCH HIGHLIGHTS P.13) WAIPARA VALLEY WINE TOUR P.13) KAIKOURA P.15) HELI-TOURING Whether you wish to sail in an extinct volcanic harbour, take in the panoramas from one P.16) E-BIKING of the world’s greatest train journeys or charter a helicopter from Otahuna’s Great Lawn into the jaw-dropping scenery of the Southern Alps, there are numerous options to help P.16) FISHING craft your time at the Lodge and the areas around us. Working with a team of the region’s P.17) HIKING finest operators, we have selected our favourite excursions to help you become immersed P.18) GOLF in the sights, sounds and flavours of the amazing place we call home. P.19) HORSEBACK RIDING LIFE AT OTAHUNA COOKING CLASS Culinary excellence is a cornerstone of the Otahuna experience. A hands-on cooking lesson with Executive Chef Jimmy McIntyre provides an enjoyable overview of the philosophies behind the Lodge’s celebrated food and wine programme as profiled in Bon Appetit, Conde Nast Traveller, and The Financial Times. Classes incorporate a harvesting visit to Otahuna’s working gardens, provide an introduction to planning menus and offer a special chance to learn first-hand cooking techniques in our kitchens before tasting the results for yourselves. -

Te Hapū O Ngāti Wheke Incorporated

TE HAPŪ O NGĀTI WHEKE INCORPORATED Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke Inc. response to Environment Canterbury draft Annual Plan 2019/20 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke Inc welcomes the opportunity to comment on the draft Environment Canterbury Annual Plan 2019/20. 1.2 Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke Inc would like to acknowledge Environment Canterbury for the opportunity to make comments on this issue. Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke Inc is deeply invested in the future of Canterbury – particularly their home of Whakaraupō and the wider Pātaka o Rākaihautū Banks Peninsula – and the many taonga tuku iho within it. Their key aspiration is to ensure that these taonga are managed “mō tatou, ā, mō kā uri a muri ake nei” (for us all and our children after us). 1.3 Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke Inc. support the intention of draft Annual Plan 2019/20, and are particularly in support of its commitment to the Pest Free Banks Peninsula (including Port Hills) / Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū Initiative. 1.4 However, there are concerns around some other issues. Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke Inc has concerns regarding: • Public transport and the funding for its provision to residents of Rāpaki • The missing recognition of Whaka-Ora Healthy Harbour 2. TE HAPŪ O NGĀTI WHEKE 3. INC 2.1 This response is made on behalf of Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke Inc in relation to the draft Annual Plan 2019/20 produced by Environment Canterbury 2.2 Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke Inc is one of the 18 papatipu rūnanga that make up Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. -

Seismic Ratings for Degrading Structural Systems

227 LANDSLIDES CAUSED BY THE 22 FEBRUARY 2011 CHRISTCHURCH EARTHQUAKE AND MANAGEMENT OF LANDSLIDE RISK IN THE IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH G. Dellow1, M. Yetton2, C. Massey3, G. Archibald3, D.J.A. Barrell3, D. Bell2, Z. Bruce3, A. Campbell1, T. Davies2, G. De Pascale2, M. Easton2, P.J. Forsyth3, C. Gibbons2, P. Glassey3, H. Grant2, R. Green2, G. Hancox3, R. Jongens3, P. Kingsbury2, J. Kupec1, D. Macfarlane2, B. McDowell2, B. McKelvey2, I. McCahon2, I. McPherson2, J. Molloy2, J. Muirson2, M. O’Halloran1, N. Perrin3, C. Price2, S. Read3, N. Traylen2, R. Van Dissen3, M. Villeneuve2 and I. Walsh2 ABSTRACT At 12.51 pm (NZST) on 22 February 2011 a shallow, magnitude MW 6.2 earthquake with an epicentre located just south of Christchurch, New Zealand, caused widespread devastation including building collapse, liquefaction and landslides. Throughout the Port Hills of Banks Peninsula on the southern fringes of Christchurch landslide and ground damage caused by the earthquake included rock-fall (both cliff collapse and boulder roll), incipient loess landslides, and retaining wall and fill failures. Four deaths from rock-fall occurred during the mainshock and one during an aftershock later in the afternoon of the 22nd. Hundreds of houses were damaged by rock-falls and landslide-induced ground cracking. Four distinct landslide or ground failure types have been recognised. Firstly, rocks fell from lava outcrops on the Port Hills and rolled and bounced over hundreds of metres damaging houses located on lower slopes and on valley floors. Secondly, over-steepened present-day and former sea-cliffs collapsed catastrophically. Houses were damaged by tension cracks on the slopes above the cliff faces and by debris inundation at the toe of the slopes. -

Significance of Substrate Soil Moisture Content for Rockfall Hazard

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2019-11 Manuscript under review for journal Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discussion started: 14 February 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Significance of substrate soil moisture content for rockfall hazard assessment Louise Mary Vick1, Valerie Zimmer2, Christopher White3, Chris Massey4, Tim Davies5 1Institute of Geosciences, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Dramsveien 201, Tromsø 9009, Norway 5 2State Water Resources Control Board, 1001 I Street, Sacramento, California 95814, USA 3Resource Development Consultants Limited, 8/308 Queen Street East, Hastings, Hawkes Bay, New Zealand 4GNS Science, 1 Fairway Drive, Avalon 5010, New Zealand 5Department of Geological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Christchurch 8041, New Zealand 10 Correspondence to: Louise M. Vick ([email protected]) ORCHID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9159-071X Abstract. Rockfall modelling is an essential tool for hazard analysis in steep terrain. Calibrating terrain parameters ensures that the model results accurately represent the site-specific hazard. Parameterizing rockfall models is challenging because rockfall runout is highly sensitive to initial conditions, rock shape, size and material properties, terrain morphology, and 15 terrain material properties. This contribution examines the mechanics of terrain scarring due to rockfall on the Port Hills of Christchurch, New Zealand. We use field-scale testing and laboratory direct-shear testing to quantify how the changing moisture content of the loessial soils can influence its strength from soft to hard, and vice versa. We calibrate the three-dimensional rockfall model RAMMS by back analysing several well-documented rockfall events, adopting dry loessial soil conditions. -

Letter with Letterhead

Media Release 28 January 2010 Ngāi Tahu Treaty Festival, Ōnuku Marae, Akaroa, Saturday 6 February Ōnuku Rūnanga will host Ngāi Tahu Treaty of Waitangi Day Commemorations, Ngāi Tahu Treaty Festival, at Ōnuku Marae, Akaroa, on Saturday 6 February. The public is welcome to attend. The day will begin with a powhiri at 9am to welcome guests, which include Governor-General Sir Anand Satyanand and Deputy Prime Minister Bill English. This will be followed by a full day of festivities including a mix of live bands and kapahaka, weaving and carving demonstrations, and a display of tribal taonga (treasures) from the extensive Canterbury Museum Louis Vangioni collection, which will be on display in the wharenui (meeting house). Upoko of Ōnuku Rūnanga George Tikao says the theme of the Ngāi Tahu Treaty Festival will centre around Ngāi Tahu’s relationship with the whenua; land. “The reason being, the significant success already regarding whenua, for example Takapūneke, the return of this historically significant land which is now blessed and cleansed and returned to the nation as an historical reserve,” says George Tikao. “That is something we can all celebrate”. Ōnuku is one of three locations in Te Waipounamu at which Ngāi Tahu signed the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. Other whenua related projects at Banks Peninsula include working to have Māori place names alongside the English place names of some culturally significant sites. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Te Waipounamu House 158 Hereford Street, PO Box 13-046 Christchurch, New Zealand Phone + 64 3 366 4344, Fax: +64 3 365 4424 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ngaitahu.iwi.nz Ngāi Tahu Treaty Festival, Ōnuku Marae, Akaroa, Saturday 6 February 0900 Assemble at front of Marae for Pōwhiri 0915 Powhiri 1010 Day Programme / House Keeping 1030 Morning Tea – VIP’s & Kaumātua in Wharekai 1100 Entertainment/Stalls 1300 Hangi lunch All Day Taonga Exhibition in the Wharenui Weaving, Carving, Arts and Crafts in marquee Various Stalls: Ngāi Tahu merchandise, Whai Rawa Savings Scheme, Department of Conservation, St John and much more. -

FT2 Earthquake Engineering Geology: Port Hills and Christchurch City

Geosciences 2013 Annual Conference of the Geoscience Society of New Zealand. Christchurch. Field Trip 2 Sunday 24th November 2013 Earthquake Engineering Geology: Port Hills and Christchurch City. Guide authors: David Bell, Janet Brehaut and Maree Hemmingsen Trip Leaders: David Bell and Valerie Zimmer Department of Geological Sciences, University of Canterbury Cover photo: Shag Rock at the entrance to the Avon‐Heathcote Estuary, modified in the Canterbury Earthquake Sequence, and now locally referred to as Shag Pile. Bibliographic reference: Bell, D.H., Brehaut, J., Hemmingsen, M. and Zimmer, V. (2013). Earthquake Engineering Geology: Port Hills and Christchurch City. In: Reid, C.M. & Hampton, S.J. (compilers). Field Trip Guides, Geosciences 2013 Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand. Geoscience Society of New Zealand Miscellaneous Publication 136B. 23 p. ISBN 978‐1‐877480‐34‐8, ISSN 2230‐4487 (print) ISSN 2230‐4495 (online) Earthquake Engineering Geology: Port Hills and Christchurch City Geosciences Health and Safety: Most of the field trip stops will be off‐street in local parks, however please take care if crossing roads. All roads are public, with some being busy and congested due to remediation work in the area. High visibility vests will be provided, so please wear these whenever not on the bus. Sturdy footwear is recommended, however we will not venture far from the coach at most locations. Route: Leave 11.00 am and travel from University of Canterbury to Sumner (Wakefield Avenue). Sumner to Redcliffs, Huntsbury Hill (Vernon Terrace), via Opawa to Porritt Park, and Dallington. Return to University of Canterbury by 5.30 pm. 2 Earthquake Engineering Geology: Port Hills and Christchurch City Geosciences Background New Zealand is located at a plate boundary between the Pacific and Australian plates (Figure 1). -

JB Et Al. 2019 Revised Manuscript

1 Geologic and geomorphic controls on rockfall hazard: how well do past rockfalls predict 2 future distributions? 3 4 Josh Borella 1,2, Mark Quigley 3,2, Zoe Krauss 4,1, Krystina Lincoln 5,1, Januka Attanayake 3, 5 Laura Stamp 5,1, Henry Lanman 6,1, Stephanie Levine 7,1, Sam Hampton 1,2, Darren Gravley 1,2 6 7 1 Frontiers Abroad, 3 Harbour View Terrace, Christchurch, 8082, New Zealand 8 2 Department of Geological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, 8041, New Zealand 9 3 School of Earth Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, 3010, Australia 10 4 Department of Geology, Colorado College, Colorado Springs, CO, 80903, USA 11 5 Department of Geosciences, Williams College, Williamstown, MA, 01267, USA 12 6 Department of Geology, Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA, 99362, USA 13 7 Department of Geology, Carleton College, Northfield, MN, 55057, USA 14 15 Correspondence: Josh Borella ([email protected]) 16 17 KEYWORDS: Rockfall hazard, boulder spatial distributions, frequency-volume distributions, 18 Canterbury Earthquake Sequence, prehistoric rockfall boulders, deforestation, rockfall 19 source characteristics, rockfall physical properties, rockfall numerical modelling, 20 Christchurch 21 22 Abstract 23 24 To evaluate the geospatial hazard relationships between recent (contemporary) rockfalls and 25 their prehistoric predecessors, we compare the locations, physical characteristics, and 26 lithologies of rockfall boulders deposited during the 2010-2011 Canterbury earthquake 27 sequence (CES) (n=185) with those deposited prior to the CES (n=1093). Population ratios of 28 pre-CES to CES boulders at two study sites vary spatially from ~5:1 to 8.5:1. This is interpreted 29 to reflect (i) variations in CES rockfall flux due to intra- and inter-event spatial differences in 30 ground motions (e.g.