Neo-Grotesk Or Neo-Grotesque Are Typefaces Designed Without a Serif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AVENIR Family

An Introduction To The AVENIR Family By Stacey Chen O V E R V I E W l Avenir was designed by Adrian Frutiger. l The typeface was first released in 1988 with three weights, before being expanded to six weights. l In 2004, together with Akira Kobayashi, Frutiger reworked the Avenir family. l Avenir has now become a common font in web, print, and graphic design, etc. l Frutiger was born in Unterseen, Switzerland 1928. l At age 16, Frutiger was apprenticed as a compositor to a printer, while taking classes in woodcuts and drawing. l With his second wife, Frutiger had two daughters, who both experienced mental health problems and committed suicide as adolescents. l Frutiger spent most of his professional career working in Paris and living in France, returning to Switzerland later in life. A D R I A N F R U T I G E R l Charles Peignot of Deberny Et Peignot recruited Frutiger based on the quality of the wood- engraved illustrations of his essay. l Impressed by the success of Futura typeface, Peignot encouraged a new, geometric sans-serif type in competition. l Frutiger disliked the regimentation of Futura, and persuaded Peignot that the new sans-serif be based on the realist model. l In 1988, Frutiger completed the family Avenir. Frutiger intended the font to be a more human version of geometric sans-serif types popular in the 1930s, such as Erbar and Futura. A D R I A N F R U T I G E R “Avenir” = “Future” French English A V E N I R i s l Futura is a geometric sans-serif typeface designed in 1927 by Paul Renner. -

Fonts for 2021!

Fonts for 2021! Amienne* Basic Class Display Fonts 1234567890 1234567890 * Font families available abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Anaconda Baveuse Abigail * 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz avbcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Argentine Belinda* Abyss* 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Arizona Benjamin* Adria Deco 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Austere Berkley* Agnes 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Ballad Script Bernhard Fashion FS Aladdin* 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Bamboo Big Fiction* Alex Brush 1234567890 1234567890 1234567890 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Banker -

The Impact of the Historical Development of Typography on Modern Classification of Typefaces

M. Tomiša et al. Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama ISSN 1330-3651 (Print), ISSN 1848-6339 (Online) UDC/UDK 655.26:003.2 THE IMPACT OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF TYPOGRAPHY ON MODERN CLASSIFICATION OF TYPEFACES Mario Tomiša, Damir Vusić, Marin Milković Original scientific paper One of the definitions of typography is that it is the art of arranging typefaces for a specific project and their arrangement in order to achieve a more effective communication. In order to choose the appropriate typeface, the user should be well-acquainted with visual or geometric features of typography, typographic rules and the historical development of typography. Additionally, every user is further assisted by a good quality and simple typeface classification. There are many different classifications of typefaces based on historical or visual criteria, as well as their combination. During the last thirty years, computers and digital technology have enabled brand new creative freedoms. As a result, there are thousands of fonts and dozens of applications for digitally creating typefaces. This paper suggests an innovative, simpler classification, which should correspond to the contemporary development of typography, the production of a vast number of new typefaces and the needs of today's users. Keywords: character, font, graphic design, historical development of typography, typeface, typeface classification, typography Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama Izvorni znanstveni članak Jedna je od definicija tipografije da je ona umjetnost odabira odgovarajućeg pisma za određeni projekt i njegova organizacija s ciljem ostvarenja što učinkovitije komunikacije. Da bi korisnik mogao odabrati pravo pismo za svoje potrebe treba prije svega dobro poznavati optičke ili geometrijske značajke tipografije, tipografska pravila i povijesni razvoj tipografije. -

Global Type.Indd

Global Type Browser Specification December 27th, 2010 Google Earth or NASA World Wind could become the basis of a somewhat new and sophis- ticated kind of archive regar- ding typefaces, type designers, foundries and type history. The time wheel allows users to select items in time. The position is in the left upper edge of the screen. Depending on the time interval, there come up diffe- rent buttoms and different types. In the right upper corner you will find the compass, similar to the time wheel different tastes. All at once, the user interface should look like this: And there is the Hot Box that comes comes up when you hit the space bar: Depending on the geographical area and the time wheel the globe will be represented more or less zoomed. Whenever there is a point of typographic interest, a hot spot gloes up. Beneath the hot spot the title and a little picture come up. If selected, the chosen point will turn into the center, and the navigation disappears. The single elements of the specific hot spot appear. Johannes Gutenberg Pietro Bembo Claude Garamond Firmin Didot Linotype typesetting machine 1982: A movie about type history from Purup Electronics, Cœbenhavn, Denmark. There should be around 200 Hot spots. Date Location Creator/company Event – 4000 Mesopotamia Phoenicians Phoenician alphabet – 3200 Egypt 1 Egyptians Hieroglyphs – 3100 Crete Minoean Linear A script – 3000 Middle america Mayans Mayan hieroglyphs – 1340 Egypt 2 Echnaton & Nofretete Monotheism – 800 Greece Hellenics Greek alphabet – 246 China 1 Qin Shihiangdi Conventions about scripts 113 Rome Imperator Trajanus Trajan’s column 200 Northern europe Scandinavian people Runes 800 Corbie Karl the Great Carolingian minuscle 1040 China 2 Delta of Yangzi Invention of printing 1452 Mainz Johannes Gutenberg 42-line bible 1470 Vienna Nicolaus Jenson Jenson 1496 Vienna Francesco Griffo Bembo 1530 Paris Claude Garamond Garamond 1737 Paris Pierre Simon Fournier Typograhic measure system 1757 Birmingham John Baskerville Baskerville 1768 Parma Giambattista Bodoni Bodoni 1896 Berlin H. -

Univers Adrian Frutiger’S Most Prominent Typeface

Beyond the Univers Adrian Frutiger’s Most Prominent Typeface by Wifany Caudenly Beyond The Univers Wifany Caudenly [2A - F09DM0623] TABLE OF CONTENTS : Exploring the Univers 4 Adrian Frutiger 6 7 Deberny & Peignot 8 Univers Weights The Frutiger Numbering 10 System Identifying Characteristics 12 14 Anatomy Comparison The great stroke of luck in my life is to have “been blessed first with an artistic feeling for shapes and second with an easy grasp of The Universe of Univers technical processes and of mathematics. 16 ~Adrian Frutiger ” 2 3 u•ni•vers Adrian Frutiger H mVDu PT i 1954 E aj s N k g e u xq dD O sX h T Br K E h Q F b Sc Gy I NUq uH ag LWyF P t p i AZ k x h l Z o kRiz n X H FG N gM N S u B W S y UTz In 1957, The Swiss e e qK z a typographer Adrian Frutiger J r designed a revolutionary C Rp typeface called Univers. N vPo n c Its simple sans-serif grotesque dF c d hj letterforms are renowned X o R Q e L for its legibility and graphic unity. t E f V Endowed with extreme versatility, k m M mB Z N Univers fulfils its duty as a utilitarian ft n JA workhorse throughout the world. W t L U AG L l vr s 4 | exploring the univers U exploring the univers | 5 Frutiger Charles Peignot invit- Peignotopurchased So, from his early adrian ed Adrian Frutiger to the rights to Pho- sketches at the Zur- work at his company ton, theifirstiphoto- i ch o s ch o o l o f o r o t h e early life Deberny & Peignot typographyimachine appliediarts,oAdrian in 1952.oThere,owh in the United States Frutigerodeveloped hi- Adrian Frutiger was born May 24, 1928 in Unterseen, Switzerland. -

Tracing Meta

MiraCosta College / oceanside MAT 155 Graphic Design 2 : Typography Min Choi // Fall 2017 TRACING META INFO ABOUT META FF Meta is a humanist sans-serif typeface family designed by Erik Spiekermann and released in 1991 through his FontFont library. According to Spiekermann, FF Meta was intended to be a “complete antithesis of Helvetica”, which he found “boring and bland”. It originated from an unused commission for the Deutsche Bundespost (West German Post Office). Throughout the 1990s, FF Meta was embraced by the international design community with Spiekermann and E. M. Ginger writing that it had been dubiously praised as the Helvetica of the 1990s. FF Meta has been adopted by numerous corporations and other organizations as a corporate typeface, for signage or in their logo. These include Imperial College London, The Weather Channel, Free Tibet, Herman Miller, Zimmer Holdings, Mozilla Corporation, Mozilla Foundation, and Fort Wayne International Airport. Over the 25 years since its inception, the FF Meta family has been extended to include eight weights and two widths, as well as additional companion families, like FF Meta Headline, FF Meta Serif, and FF Meta Correspondence. The original FF Meta typeface has extended to a very flexible superfamily, as fresh as it was when it was born. In 2011, the Museum of Modern Art in New York added digital typefaces to its permanent collection for the very first time. Naturally, because of its significance to typography, FF Meta was one of the works included. FF Meta debuted at MoMA as part of the “Standard Deviations” installation in the contemporary design gallery. -

INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION, to an Insightful 866 SECOND AVENUE, 18 Editorial Mix

INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION TYPEFACE UPPER AND LOWER CASE , THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF T YPE AND GRAPHI C DESIGN , PUBLI SHED BY I NTE RN ATIONAL TYPEFAC E CORPORATION . VO LUME 2 0 , NUMBER 4 , SPRING 1994 . $5 .00 U .S . $9 .90 AUD Adobe, Bitstream &AutologicTogether On One CD-ROM. C5tta 15000L Juniper, Wm Utopia, A d a, :Viabe Fort Collection. Birc , Btarkaok, On, Pcetita Nadel-ma, Poplar. Telma, Willow are tradmarks of Adobe System 1 *animated oh. • be oglitered nt certain Mrisdictions. Agfa, Boris and Cali Graphic ate registered te a Ten fonts non is a trademark of AGFA Elaision Miles in Womb* is a ma alkali of Alpha lanida is a registered trademark of Bigelow and Holmes. Charm. Ea ha Fowl Is. sent With the purchase of the Autologic APS- Stempel Schnei Ilk and Weiss are registimi trademarks afF mdi riot 11 atea hmthille TypeScriber CD from FontHaus, you can - Berthold Easkertille Rook, Berthold Bodoni. Berthold Coy, Bertha', d i i Book, Chottiana. Colas Larger. Fermata, Berthold Garauannt, Berthold Imago a nd Noire! end tradematts of Bern select 10 FREE FONTS from the over 130 outs Berthold Bodoni Old Face. AG Book Rounded, Imaleaa rd, forma* a. Comas. AG Old Face, Poppl Autologic typefaces available. Below is Post liedimiti, AG Sitoploal, Berthold Sr tapt sad Berthold IS albami Book art tr just a sampling of this range. Itt, .11, Armed is a trademark of Haas. ITC American T}pewmer ITi A, 31n. Garde at. Bantam, ITC Reogutat. Bmigmat Buick Cad Malt, HY Bis.5155a5, ITC Caslot '2114, (11 imam. -

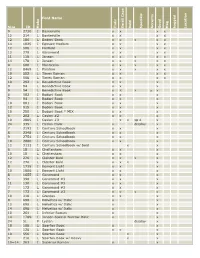

Size ID M Ak E Font Name I Talic S M All C Ap S Bold S P E C Ials Accents

Font Name Size ID Make Italic Small Caps Bold Specials Accents Good Mag bagged Location 9 2730 I Baskerville x x x x 12 314 L Baskerville x x x x 12 186 L Bodoni Book x x x x x 14 1025 I Egmont Medium x x x x 12 508 L Fairfield x x x x 12 278 L Garamond x x x x 11 118 L Janson x x x x x 14 178 L Janson x x x x x 9 600 L Monticello x x x x x 12 8469 L Palatino x x x x x 10 552 L Times Roman x x x x 12 568 L Times Roman x x x x 10 292 L Benedictine Book x x x 9 94 L Benedictine Book x x x 9 94 L Benedictine Book x X x x x 6 582 I Bodoni Book x x x 7 94 L Bodoni Book x x x 10 801 I Bodoni Book x x x 12 915 I Bodoni Book x x x 10 250 L Bodoni Book * MIX x x x 6 202 L Caslon #2 x x x 10 2885 I Caslon #3 x x sp 4 x 24 335 L Caslon Italic x display x 7 2191 I Century Schoolbook x x x 8 2348 I Century Schoolbook x x x 9 2754 I Century Schoolbook x x x 10 2880 I Century Schoolbook x x x 12 3111 I Century Schoolbook w/ bold x x 6 18 L Cheltenham x x x 10 18 L Cheltenham x x x 12 276 L Cloister Bold x x x x 12 276 L Cloister Bold x x x x 8 1715 I Egmont Light x x x 10 1806 I Egmont Light x x x 8 1655 I Garamond x x x 6 398 L Garamond #3 x x x 11 130 L Garamond #3 x x x 7 172 L Garamond #3 x x x 7 172 L Garamond #3 x x x x 10 318 L Granjon x x x 8 698 L Helvetica w/ Italic x x 12 698 L Helvetica w/ Italic x x 14 698 L Helvetica w/ Italic x x 10 264 I Inferior Roman x x 14 178S L Janson Special Narrow Italic x x 24 5L P Lydian display x 18 108 L Spartan Book x x 9 128 L Sparton Book x x x 10 556 L Sparton Book x x 9 216 L Sparton Book w/ Heavy x x -

Press Release

segni 16.03 _ 18.05.2019 esemplari Palazzo della Pilotta, Biblioteca Palatina cogitations and digressions on the shape of writing to celebrate the bi-centenary of the Manuale tipografico 8 by Giambattista Bodoni: manuals, printers’catalogues and posters in an exhibition organised by the Museo Bodoniano of Parma Only recently the year ended in which the bi-centenary of the publication of Giambattista Bodoni’s Manuale tipografico occurred, and the occasion has prompted an exhibition and study day organised by the Fondazione Museo Bodoniano of Parma. ¶ The manual was published posthumously by Bodoni’s widow in order to bring to completion a long-matured project taken on by her husband. It consists of a collection of 665 different alphabets and a series of around 1,300 friezes, as well as a foreword in which Bodoni lays out some of his working methods. ¶ There was a previous collection of typefaces printed by Bodoni in 1788, at the time also entitled Manuale tipografico, but the work lacks a preface or other explanatory text. It is probable that the letter founder from Parma had borrowed the title from a small technical manual by Fournier, the Manuel typographique of 1764, but in reality the two volumes, although sharing the same name, were objects with very different functions. Indeed, Fournier’s was a manual in the real sense of the term, an explanatory publication describing the essential elements of the complex activity of the letter founder, from punch-cutting to producing matrices and ultimately moveable characters. Whereas that of Bodoni was a sample book displaying typefaces and ornaments that he had designed. -

Tv38bigelow.Pdf

Histoire de l’Ecriture´ Typographique — le XXi`eme si`ecle (The History of Typographic Writing—The 20th century). Jacques Andr´e, editorial direction. Atelier Perrousseaux, Gap, France, 2016. http://www.adverbum.fr/atelier-perrousseaux Review and summaries by Charles Bigelow (TUGboat vol.38, 2017). https://tug.org/books/#andre vol.1 TUGboat38:1,pp.18–22 vol.2, ch.1–5 TUGboat 38:2, pp.274–279 vol.2, ch.6–8+ TUGboat 38:3, pp.306–311 The original publication, as reviewed, was in two volumes: Tome I/II, de 1900 `a1950. ISBN 978-2-36765-005-0, tinyurl.com/ja-xxieme. 264 pp. Tome II/II, de 1950 `a2000. ISBN 978-2-36765-006-7, tinyurl.com/ja-xxieme-ii. 364 pp. These are the last two volumes in the series The History of Typographical Writing, comprised of seven volumes in all, from the beginning of printing with Gutenberg through the 20th century. All are in French. The individual volumes and the series as a whole are available in various electronic and print formats; please see the publisher’s web site for current offerings. ❧ ❧ ❧ 18 TUGboat, Volume 38 (2017), No. 1 Review and summaries: The History of phy had begun to supplant print itself, because text Typographic Writing — The 20th century display and reading increasingly shifted from paper Volume 1, from 1900 to 1950 to computer screen, a phenomenon now noticed by nearly all readers and publishers. Charles Bigelow In the 20th century, typography was also trans- Histoire de l’Ecriture´ Typographique — le XXi`eme formed by cultural innovations that were strikingly si`ecle; tome I/II, de 1900 `a1950. -

Erik Spiekermann, Born 1947, Studied History of Art and English in Berlin

Erik Spiekermann, born 1947, studied History of Art and English in Berlin. He is information architect, type designer (ff Meta, ff MetaSerif, itc Officina, ff Govan, ff Info, ff Unit, LoType, Berliner Grotesk and many corporate typefaces) and author of books and articles on type and typography. He was founder (1979) of MetaDesign, Germany's largest design firm with offices in Berlin, London and San Francisco. Projects included corporate design programmes for Audi, Skoda, Volks wagen, Lexus, Heidelberg Printing and wayfinding projects like Berlin Transit, Düsseldorf Airport and many others. In 1988 he started FontShop, a company for production and distribution of electronic fonts. Erik is board member of ATypI and the German Design Council and Past President of the istd, International Society of Typographic Designers, as well as the iiid. In 2001 he left MetaDesign and now runs SpiekermannPartners with offices in Berlin, London and San Francisco. In 2001 he redesigned The Economist magazine in London. His book for Adobe Press,“Stop Stealing Sheep” is in its second edition and a German and a Russian version. His corporate font family for Nokia was released in 2002. In 2003 he received the Gerrit Noordzij Award from the Royal Academy in Den Haag. His type system DB Type for Deutsche Bahn was awarded the Federal German Design Prize in gold for 2006. In May 2007 he was the first designer to be elected into the Hall of Fame by the European Design Awards for Communication Design. Erik is Honorary Professor at the University of the Arts in Bremen and in 2006 received an honorary doctorship from Pasadena Art Center. -

When Is Typography Conceptual? Steen Ejlers, the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture

2013 | Volume III, Issue 1 | Pages 1.1-1.10 When is typography conceptual? Steen Ejlers, The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture A conceptual artwork is not necessarily constituted the sentences disappeared in an even vertical/ by exceptional practical skill, sublime execution or horizontal pattern of letters: beautiful and orderly - whatever might otherwise regularly characterize and difficult to access. “fine art”. Instead, the effort is seated in the Both of these strategies of making stone preparatory process of thought – or as Sol Lewitt inscriptions appear strange to our eyes but once put it: “The idea becomes a machine that apparently it must have worked out. And even so! makes art” (LeWitt 1967). The conceptual work of – the everyday frequency of stone inscriptions that art typically speaks primarily to the intellect and not had to be decoded by the ancient Greeks can hardly necessarily to an aesthetic/sensual experience. be likened to the text bombardment, let alone the But what about the notion of “conceptual reading process, that we live with today. Moreover, type”? Could this be, in a way that is analogous to the Greek inscriptions, like the Roman ones of “conceptual art”, typefaces that do not necessarily the same time, consisted solely of capital letters, function by virtue of their aesthetic or functional all of which could, characteristically enough, be qualities but are interesting alone owing to the deciphered when laterally reversed. However, when foregoing idea-development process? Or is a boustrophedon was brought into practice with the typeface which, in its essential idiom, conveys a Latin alphabet’s majuscule and minuscule letters, message or an idea, conceptually? In what follows, I a number of confusing situations could arise and will try to examine these issues by invoking a series of crucial moments in the history of typeface, from antiquity up to the twenty-first century.