Guangdong Model”: Towards Real Ngos?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guangdong Information

Guangdong Information Overview Guangdong’s capital and largest city is Guangzhou. It is the southernmost located province on the China mainland. Guangdong is China’s most populous province with 110,000,000 inhabitants. With an area of 76,000 sq mi (196, 891 sq km) it is China’s 15th largest province. Its sub-tropic climate provides a comfortable 72°F (22°C) annual average. Cantonese is spoken by the majority of the population. Known nowadays for being a modern economic powerhouse and a prime location for trade, it also holds a significant place in Chinese history. Guangdong Geography Guangdong is located in the south of the country and faces the South China Sea. The long hilly coast stretches 2670 miles (4.300 km) totaling one fifth of the country’s coastline. There are hundreds of small islands located in the Zhu Jiang Delta, which is where the Dong Jiang, Bei Jiang and Guang Jiang rivers converge. Among these islands are Macao and Hong Kong, the latter of which stretches its political boundaries over a portion of the mainland as well. Hainan province, an island offshore across from the Leizhou Peninsula in the southwest, was part of Guangdong until 1988 when it became a separate province. Guangzhou and Shenzhen are both located on the Zhu Jiang River. Guangdong China borders Hunan, Jiangxi, Fujian, and Hainan provinces in addition to the Gunagzhuang Autonomous Region, Hong Kong, and Macao. Guangdong Demographics Guangdong China is composed of 99% Han, .7% Zhuang, and .2% Yao. The Hui, Manchu, and She make up most of the remaining .1%. -

Test Report Guangzhou Quality Supervision and Testing Institute

Test Report Test Report No.: 轻委2020-05-0955 Applicant: Hunan Kangweining Medical Device- s Co., Ltd Sample Name: Disposable medical mask(non-ste- rile) Type and Specification: Flat Ear hanging 17.5cm×9.5cm Completion Date: 2020-06-02 Guangzhou Quality Supervision and Testing Institute (GQT) Important Statement 1. Guangzhou Quality Supervision and Testing Institute (GQT) is the products quality super- vision and testing organization that is set up by the Government and in charge by Guangzhou Administration for Market Regulation. GQT is a social public welfare institution that pro- viding technical support for the government to strengthen the market supervision and ad- ministration, and also accepting commissioned inspection. 2. GQT and the National Quality Supervision and Testing center (center) and the Products Quality Supervision and Testing Station (station) guarantee that the inspection is scien- tific, impartial and accurate and are responsible for the testing result and also keep con- fidentiality of the samples and technical information provided by the applicants. 3. Any report without the signatures of the tester, checker and approver, or altered, or without the special chapter for Inspection and Testing of the Institute (center/station), or without the special testing seal , will be taken as invalid. The test shall not be par- tial copied, picked up and tampered without the authorization of GQT (Center/ Station). 4. The entrusted testing is only valid to the provided samples.The applicant shall not use the inspection results without authorization of GQT (Center/ Station) for undue publicity. 5. The sample and relevant information provided by the applicant, GQT (Center/Station)is not responsible for its authenticity and integrity. -

Analysis of Dissolved Oxygen and Nutrients in Zhanjiang Bay and the Adjacent Sea Area in Spring

sustainability Article Analysis of Dissolved Oxygen and Nutrients in Zhanjiang Bay and the Adjacent Sea Area in Spring Dongyang Fu 1, Yafeng Zhong 1,*, Fajin Chen 2,*, Guo Yu 1 and Xiaolong Zhang 1 1 College of Electronic and Information Engineering, Guangdong Ocean University, Zhanjiang 524088, China; [email protected] (D.F.); [email protected] (G.Y.); [email protected] (X.Z.) 2 College of Ocean and Meteorology, Guangdong Ocean University, Zhanjiang 524088, China * Correspondence: zyff[email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (F.C.) Received: 10 December 2019; Accepted: 21 January 2020; Published: 24 January 2020 Abstract: As a semi-closed bay with narrow bay mouths, the distribution of nutrients in Zhanjiang Bay was different from bays with open bay mouths and rivers with large flows. It is important to study the water quality of Zhanjiang Bay to determine the impact of human activities on this semi-closed bay. Based on field survey data in spring, the spatial distribution of nutrients and other physico-chemical parameters was investigated, in order to study the geochemical characteristics of nutrients in semi-closed bays. Higher nutrient concentrations were observed in the inner and outer bays, but lower concentrations were observed at the bay mouth. With other analyses of physico-chemical parameters, the higher nutrient concentrations in the inner bay originated mainly from the diluted freshwater input from local developments and rivers. With the strong flow that exists along the western coast of Guangdong Province, the higher dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) and SiO3–Si concentrations along the outer bay may be influenced by discharge from local cities in western Guangdong Province. -

SAFETY DATA SHEET for CHEMICAL PRODUCTS 4��1=画画� Testir阳 、;;;;;;;? Servic� (SDS) Report No

/叭他wbest SAFETY DATA SHEET FOR CHEMICAL PRODUCTS 4��1=画画� Testir阳 、;;;;;;;? Servic� (SDS) Report No. N 82020030926 Date: March 19, 2020 Page: 1/9 Applicant Name SING뜏ONG ASIA PACIFIC (BOLUO)CO.,LTD. Applicant Address PING’AN INDUSTRIAL PARK,BAITANG TOWN,BOLUO COUNTY HUIZHOU CITY GUANGDONG PROVINCE CHINA Product Name INSTANT HAND SANITIZER Received Date March 18 2020 Compilation Period March 18, 2020 to March 19, 2020 Regulatory Requirements As requested by the applicant, the Safety Data Sheet is prepared according to EU CLP Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008. Signed for and on behalf of Guangdong NewBest Testing Service Co., Ltd. ; 一阳 This report cannot be reproduced partly, with ut prior written permission of Laboratory.Any unauthorized alteration,f rgery or falsification f the content of。 this d cument is unlawful. Unless otherwise stated the results shown in this。 test report refer only。 to the sample (s) tested.。 No.1, 8/F, Shengfeng Road, Venture Industrial Park, Xinhe Community,W叫iang District, Dongguan City, China Tel: 400-877-6107 Website: www nbtscn.com Fax: 0769-22777508 E-mail: newbest@nbtscn c。m /叭他wbest SAFETY DATA SHEET FOR CHEMICAL PRODUCTS 4��1=画画� Testir阳 、;;;;;;;? Servic� (SDS) Report No. N 82020030926 Date: March 19, 2020 Page: 3/9 H319 Causes serious eye irritation 2.5 Precautionary description: P210 Keep away from heat, hot surfaces, sparks, open flames and other ignition sources. No smoking. P234 Keep only in original packaging. P235 Keep cool - may be omitted if P411 is given on the label. P240 Ground and bond container and receiving equipment. - if electrostatically sensitive and able to generate an explosive atmosphere. -

China's Technology Mega-City an Introduction to Shenzhen

AN INTRODUCTION TO SHENZHEN: CHINA’S TECHNOLOGY MEGA-CITY Eric Kraeutler Shaobin Zhu Yalei Sun May 18, 2020 © 2020 Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP SECTION 01 SHENZHEN: THE FIRST FOUR DECADES Shenzhen Then and Now Shenzhen 1979 Shenzhen 2020 https://www.chinadiscovery.com/shenzhen-tours/shenzhen-visa-on- arrival.html 3 Deng Xiaoping: The Grand Engineer of Reform “There was an old man/Who drew a circle/by the South China Sea.” - “The Story of Spring,” Patriotic Chinese song 4 Where is Shenzhen? • On the Southern tip of Central China • In the south of Guangdong Province • North of Hong Kong • Along the East Bank of the Pearl River 5 Shenzhen: Growth and Development • 1979: Shenzhen officially became a City; following the administrative boundaries of Bao’an County. • 1980: Shenzhen established as China’s first Special Economic Zone (SEZ). – Separated into two territories, Shenzhen SEZ to the south, Shenzhen Bao-an County to the North. – Initially, SEZs were separated from China by secondary military patrolled borders. • 2010: Chinese State Council dissolved the “second line”; expanded Shenzhen SEZ to include all districts. • 2010: Shenzhen Stock Exchange founded. • 2019: The Central Government announced plans for additional reforms and an expanded SEZ. 6 Shenzhen’s Special Economic Zone (2010) 2010: Shenzhen SEZ expanded to include all districts. 7 Regulations of the Special Economic Zone • Created an experimental ground for the practice of market capitalism within a community guided by the ideals of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” • -

Teachers' Guide to Set Works and the World Focus

Cambridge Secondary 2 Teachers’ Guide to set works and the World Focus Cambridge IGCSE® (9–1) Music 0978 For centres in the UK For examination in June and November 2019. Version 1 Cambridge International Examinations is part of the Cambridge Assessment Group. Cambridge Assessment is the brand name of the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate (UCLES), which itself is a department of the University of Cambridge. UCLES retains the copyright on all its publications. Registered centres are permitted to photocopy any material that is acknowledged to a third party even for internal use within a centre. ® IGCSE is the registered trademark Copyright © UCLES September 2017 Contents Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) .......................................................................2 Italian Symphony No. 4 in A major Op. 90 (Movements 2 and 4) 2 1 Background 2 2 Instruments 3 3 Directions in the score 3 4 Techniques 4 5 Structure and form 5 6 Commentary 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) ......................................................10 Clarinet Concerto in A major, K622 (Movement 1) 10 1 Background 10 2 Instruments 11 3 Directions in the score 12 4 Techniques 12 5 Structure and form 13 6 Commentary 14 World Focus for 2019: China ...........................................................................18 The ensemble music of China 18 1 Historical background 18 2 Types of silk-and-bamboo ensemble 19 3 Overall musical features of Chinese music 24 4 Notation and transmission 25 Cambridge IGCSE (9–1) Music 0978 Teachers’ Guide to set works and The World Focus for 2019. Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) Italian Symphony No. 4 in A major Op. 90 (Movements 2 and 4) There are a few small differences between editions of the score of this work (e.g. -

China - Peoples Republic Of

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 12/22/2010 GAIN Report Number: CH10609 China - Peoples Republic of Post: Guangzhou Guangdong Province- Dynamic Gateway to South China Report Categories: Market Development Reports Approved By: Jorge, Sanchez Prepared By: Jericho, Li Report Highlights: Guangdong is one of China’s economic powerhouses, its provincial capital Guangzhou and economic hub Shenzhen are amongst the most populous and important metropolises in China. Its GDP has topped the rankings since 1989 amongst all provincial-level divisions. In 2009, Guangdong province had the highest GDP per capita in China. Per annum, Guangdong contributes approximately 12 percent of China's national economic output, and is home to the production facilities and offices of a wide-ranging set of multinational and export-driven Chinese corporations. Twice a year, Guangdong also hosts the largest Import and Export Fair in China: the Canton Fair in Guangzhou. General Information: Overview Located on the Southeastern Coast of the People’s Republic of China, Guangdong is China’s southern most provinces with a coastline of over 4,300 kilometers. The province has an area of 197,100 sq km and is bound by the South China Sea to the south, and along its coast are Hong Kong and Macau. Also bordering Guangdong are Fujian, Jiangxi, and Hunan provinces and Guangxi autonomous region. Guangdong is one of China’s economic powerhouses, its provincial capital Guangzhou and economic hub Shenzhen are amongst the most populous and important metropolises in China. -

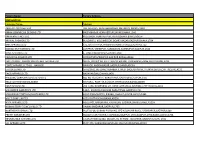

No. Manufacture Name Address Country Certificate of Registration No. Date of Registration Date of Expiry 1 DIGO CREATIVE ENTERPR

รายชื่อโรงงานที่ทําผลิตภัณฑในตางประเทศที่ไดรับการขึ้นทะเบียน List of Registered Foreign Manufacturer ขอบขายตามมาตรฐานเลขที่ มอก.685 เลม 1-2540 ของเลน TIS 685-2540 : Toys Part 1 General requirements No. Manufacture name Address Country Certificate of Date of Date of Expiry Registration No. Registration 1 DIGO CREATIVE ENTERPRISE NO. 126, LANE 899, GUANGTAI, JINHUI TOWN, PEOPLE' S R685-161 31-Mar-2017 29-Mar-2020 CO., LTD FENGXIAN DISTRICT, SHANG HAI REPUBLIC OF CHINA 2 DONG GUAN YONG RONG NAN QU INDUSTRIAL ZONE, SHA TOU PEOPLE' S R685-164 21-Mar-2017 19-Mar-2020 PLASTIC PRODUCTS CO., VILLAGE, CHANGAN TOWN, DONGGUAN CITY REPUBLIC OF LTD. (SHA TOU BRANCH) GUANGDONG PROVINCE CHINA 3 DONGGUAN KING SURPRISE HE'NAN INDUSTRIAL DISTRICT, JINXIA, PEOPLE' S R685-169 20-Mar-2017 18-Mar-2020 INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. CHANG'AN TOWN, DONGGUAN CITY, REPUBLIC OF GUANDONG PROVINCE CHINA 4 DONGGUAN ZHONGMA TOYS FUYONG VILLAGE, WANGNIUDUN TOWN, PEOPLE' S R685-172 8-May-2017 6-May-2020 CO., LTD. DONGGUAN CITY, GUANGDONG PROVINCE. REPUBLIC OF CHINA 1/57 รายชื่อโรงงานที่ทําผลิตภัณฑในตางประเทศที่ไดรับการขึ้นทะเบียน List of Registered Foreign Manufacturer ขอบขายตามมาตรฐานเลขที่ มอก.685 เลม 1-2540 ของเลน TIS 685-2540 : Toys Part 1 General requirements No. Manufacture name Address Country Certificate of Date of Date of Expiry Registration No. Registration 5 FORTE-MIND 68 XINAN ROAD, BEIHAI INDUSTRIAL ZONE, PEOPLE' S R685-242 20-Jun-2017 19-Jun-2020 INDUSTRIAL(BEIHAI) GUANGXI REPUBLIC OF COMPANY LIMITED CHINA 6 GD-TSENG ENTERPRISE CO., NO. 474-1, YIJIAO ST., EAST DIST., CHIAYI CITY TAIWAN R685-179 15-May-2017 13-May-2020 LTD. 7 GUANGDONG ZHIGAO THE 3 rd INDUSTRIAL DISTRICT,JUZHOU, PEOPLE' S R685-183 10-Apr-2017 8-Apr-2020 CULTURAL & CREATIVE INC. -

Research on the Optimization Path of Zhuhai's Industrial Structure In

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 126 5th International Conference on Financial Innovation and Economic Development (ICFIED 2020) Research on the Optimization Path of Zhuhai’s Industrial Structure in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area Yu Yu li Zhuhai College of Jilin University, Zhuhai, Guangdong, China [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: Zhuhai, industrial structure, Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area cooperation Abstract: Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area is an urban agglomeration composed of two special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macao and nine cities of Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Foshan, Zhongshan, Dongguan, Huizhou, Jiangmen and Zhaoqing. It is an important space carrier for China to build a world-class urban agglomeration and participate in global competition. The construction of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area focuses on promoting infrastructure connectivity, improving the level of market integration, building an international science and technology innovation center, establishing a modern industrial system of coordinated development, and co-building a financial core circle, which has many possibilities for coordinated development with Zhuhai, a core city on the West Bank of the Pearl River Estuary. Zhuhai has its own inherent location advantages and unique industrial pattern, but it is also facing problems such as uncoordinated industrial structure, low economic quality and weak development foundation. Based on the interpretation of Zhuhai's industrial structure, taking Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area as a development opportunity for Zhuhai, this paper puts forward the research on the optimization path of Zhuhai's industrial structure, such as promoting agricultural industrialization and modernization, improving the layout of modern industrial system, and accelerating the development of modern service industry. -

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI, -

The Story of Shenzhen

The Story of Shenzhen: Its Economic, Social and Environmental Transformation. UNITED NATIONS HUMAN SETTLEMENTS PROGRAMME THE STORY OF SHENZHEN P.O. Box 30030, Nairobi 00100, Kenya Its Economic, Social and Environmental Transformation [email protected] www.unhabitat.org THE STORY OF SHENZHEN Its Economic, Social and Environmental Transformation THE STORY OF SHENZHEN First published in Nairobi in 2019 by UN-Habitat Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2019 All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) P. O. Box 30030, 00100 Nairobi GPO KENYA Tel: 254-020-7623120 (Central Office) www.unhabitat.org HS Number: HS/030/19E ISBN Number: (Volume) 978-92-1-132840-0 The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers of boundaries. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the United Nations, or its Member States. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. Cover Photo: Shenzhen City @SZAICE External Contributors: Pengfei Ni, Aloysius C. Mosha, Jie Tang, Raffaele Scuderi, Werner Lang, Shi Yin, Wang Dong, Lawrence Scott Davis, Catherine Kong, William Donald Coleman UN-Habitat Contributors: Marco Kamiya and Ananda Weliwita Project Coordinator: Yi Zhang Project Assistant: Hazel Kuria Editors: Cathryn Johnson and Lawrence Scott Davis Design and Layout: Paul Odhiambo Partner: Shenzhen Association for International Culture Exchanges (SZAICE) Table of Contents Foreword .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

22-Guangdong Zhuhai Gaolan Port.Indd

Immersive Projection Case Study www.digitalprojection.co.uk Immersive Projection - Guangdong, China Overview: Guangdong Zhuhai Gaolan Port Economic Zone Planning Pavilion, China A total of 8 x 20,000 Lumen TITAN Super Quads were used to create the stunning Gaolan Port Economic Zone Planning Pavilion in Guangdong, China. It is an installation designed to promote the area and attract investment to the newly created economic development zone. The implementation of Special Economy Zone means that the city will grow as a powerful modern port city, science and education city, scenic and tourism city, and as a regional hub for transportation. [1] Projector Requirements As this is one of the most important large-scale comprehensive harbor industry zones of South China, with a focus on the equipment manufacturing, petrochemical and energy industries, the installation required a proven, reliable projection solution, with build in Edge-Blending and a high brightness output, so the TITAN Super Quad was specified into the project. The screens are the largest electric elevation screens in China, with the front screen at 22 meters long and 8.5 meters high. The screens on both sides are 33 meters long and 8.5 meters high, creating a stunning immersive experience for all visitors to fully experience the overall appearance and future planning of the economic development zone. TITAN Super Quad Key Features of TITAN Super Quad - 20,000 Lumens - Small, Light, Bright and Quiet chassis - SX+, 1080p and WUXGA Resolutions - Long life, power efficient HID Lamps - Built in Warp & Edge Blend - Factory Calibrated Colour with enhanced 7 Point (P7) Colour System - Precision Engineered, strong and durable DIGITAL PROJECTION, LTD GREENSIDE WAY, MIDDLETON MANCHESTER, UK.