Thurgood Marshall: Warrior at the Bar, Rebel on the Bench by Michael D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jew Taboo: Jewish Difference and the Affirmative Action Debate

The Jew Taboo: Jewish Difference and the Affirmative Action Debate DEBORAH C. MALAMUD* One of the most important questions for a serious debate on affirmative action is why certain minority groups need affirmative action while others have succeeded without it. The question is rarely asked, however, because the comparisonthat most frequently comes to mind-i.e., blacks and Jews-is seen by many as taboo. Daniel A. Farberand Suzanna Sherry have breached that taboo in recent writings. ProfessorMalamud's Article draws on work in the Jewish Studies field to respond to Farberand Sherry. It begins by critiquing their claim that Jewish values account for Jewish success. It then explores and embraces alternative explanations-some of which Farberand Sheny reject as anti-Semitic-as essentialparts of the story ofJewish success in America. 1 Jews arepeople who are not what anti-Semitessay they are. Jean-Paul Sartre ha[s] written that for Jews authenticity means not to deny what in fact they are. Yes, but it also means not to claim more than one has a right to.2 Defenders of affirmative action today are publicly faced with questions once thought improper in polite company. For Jewish liberals, the most disturbing question on the list is that posed by the comparison between the twentieth-century Jewish and African-American experiences in the United States. It goes something like this: The Jews succeeded in America without affirmative action. In fact, the Jews have done better on any reasonable measure of economic and educational achievement than members of the dominant majority, and began to succeed even while they were still being discriminated against by this country's elite institutions. -

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER What national organization was founded on President National Association for the Arts Advancement of Colored People (or Lincoln’s Birthday? NAACP) 2 In 1905 the first black symphony was founded. What Sports Philadelphia Concert Orchestra was it called? 3 The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in what Sports 1852 4 year? Entertainment In what state is Tuskegee Institute located? Alabama 5 Who was the first Black American inducted into the Pro Business & Education Emlen Tunnell 6 Football Hall of Fame? In 1986, Dexter Gordan was nominated for an Oscar for History Round Midnight 7 his performance in what film? During the first two-thirds of the seventeenth century Science & Exploration Holland and Portugal what two countries dominated the African slave trade? 8 In 1994, which president named Eddie Jordan, Jr. as the Business & Education first African American to hold the post of U.S. Attorney President Bill Clinton 9 in the state of Louisiana? Frank Robinson became the first Black American Arts Cleveland Indians 10 manager in major league baseball for what team? What company has a successful series of television Politics & Military commercials that started in 1974 and features Bill Jell-O 11 Cosby? He worked for the NAACP and became the first field Entertainment secretary in Jackson, Mississippi. He was shot in June Medgar Evers 12 1963. Who was he? Performing in evening attire, these stars of The Creole Entertainment Show were the first African American couple to perform Charles Johnson and Dora Dean 13 on Broadway. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

Mr. Justice Stanton by James W

At Sidebar Mr. Justice Stanton by James W. Satola I love U.S. Supreme Court history. Sometimes, the more arcane the better. So, for my At Sidebar con- tribution, I want to share a little bit of what I love.1 Perhaps calling to mind the well-known story behind Marbury v. Madison, here is a lesser-known story of a presidential commission not delivered on time (though in this case, it was not anyone’s fault). The story of Mr. Justice Edwin M. Stanton.2 James W. Satola is an As one walks through the Grand Concourse of attorney in Cleveland, Ohio. From 2010 to the Ohio Supreme Court building in Columbus, Ohio 2016, he served as (officially, the Thomas J. Moyer Ohio Judicial Center, an FBA Circuit Vice which had a first life as the “Ohio Departments Build- President for the Sixth ing,” opening in 1933, then restored and reopened as Circuit, and from 2002 the home of the Ohio Supreme Court in 2004), one’s to 2003, he was Presi- dent of the FBA Northern eye is drawn to nine large bronze plaques mounted District of Ohio Chapter. on the East Wall, each showcasing one of the U.S. © 2017 James W. Satola. Supreme Court justices named from Ohio.3 This story All rights reserved. is about the fourth plaque in that series, under which reads in brass type on the marble wall, “Edwin Mc- Masters Stanton, Justice of the United States Supreme Court, 1869-1869.” Justice Stanton? One finds no mention of “Justice Stanton” among the lists of the 113 men and women who have served on the Supreme Court of the United States. -

For Neoes on Newspapers

Careers For Neoes On Newspapers * What's Happening, * What the Jobs Are r * How Jobs Can Be Found nerican Newspaper Guild (AFL-CIO, CLC) AMERICAN NEWSPAPER GUILD (AFL-CIO, CLC) Philip Murray Building * 1126 16th Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 PRESIDENT: ARTHUR ROSENSTOCK EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT: WILLIAM J. FARSON SECRETARY-TREASURER: CHARLES A. PERLIK, JR REGIONAL VICE PRESIDENTS Region 1 DANIEL A. McLAUGHLIN, North Jersey Region 4 ROBERT J. HICKEY, Son Jose Region 2 RICHARD LANE, Memphis Region 5 EDWARD EASTON, JR., New York Region 3 JAMES B. WOODS, St. Louis Region 6 WILLIAM H. McLEMAN, Vancouver VICE PRESIDENTS AT LARGE JACK DOBSON, Toronto MARSHALL W. SCHIEWE, Chicago GEORGE MULDOWNEY, Wire Service NOEL WICAL, Cleveland KENNETH RIEGER, Toledo HARVEY H. WING, San Francisco-Oakland . Ws.. - Ad-AA1964 , s\>tr'id., ofo} +tw~ i 7 I0Nle0 Our newspapers, which daily report the rising winds of the fight for equal rights of minority groups, must now take a first hand active part in that fight as it affects the hiring, promotion, and upgrading of newspaper employes In order to improve the circumstances of an increas- ing number of minority-group people, who are now turned aside as "unqualified" for employment and pro- motion, we seek . a realistic, down-to-earth meaning- ful program, which will include not merely the hiring of those now qualified without discrimination as to race, age, sex, creed, color, national origin or ancestry, but also efforts through apprenticeship training and other means to improve and upgrade their qualifications. Human Rights Report American Newspaper Guild Convention Philadelphia, July 8 to 12, 1963 RELATIONSorLIS"WY JUL 23196 OF CALFORNIA UHI4Rt5!y*SELY NEWSPAPER jobs in the United States are opening to Negroes for the first time. -

BROWN V. BOARD of EDUCATION: MAKING a MORE PERFECT UNION

File: Seigenthaler.342.GALLEY(7) Created on: 5/9/2005 4:09 PM Last Printed: 7/5/2005 9:17 AM BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION: MAKING A MORE PERFECT UNION John Seigenthaler* It is impossible for me to reflect on Brown v. Board of Educa- tion1 and its meaning these five decades later without revisiting in my mind’s eye the white Southern racist society of my youth and young adulthood. That was a time when my hometown, Nashville, Tennessee, was as racially segregated as any city in South Africa at the height of Apartheid; when every city in the South, large and small, was the same; when African-American residents of those communities were denied access to any place and every place they might need or wish to go. The legal myth of “separate but equal” had cunningly banned black citizens from every hospital, school, restaurant, trolley, bus, park, theater, hotel, and motel that catered to the white public. These tax-paying citizens were denied access to these places solely on the basis of their race by tradition, custom, local ordi- nance, state statute, federal policy, and by an edict of the United States Supreme Court fifty-eight years before Brown in Plessy v. Ferguson.2 In too many of these cities, black citizens were even denied access to the ballot box on election day. The posted signs of the times read, “White Only.” If you never saw those signs, it is difficult to imagine their visible presence in every city hall, county courthouse, and public building, including many federal buildings. -

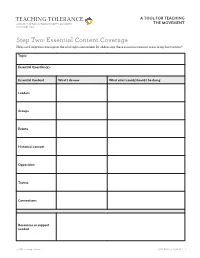

Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How Can I Improve Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement by Addressing These Essential Content Areas in My Instruction?

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: Essential Question(s): Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should I be doing Leaders Groups Events Historical context Opposition Tactics Connections Resources or support needed © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage (SAMPLE) How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should be doing Leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy A. Philip Randolph Wilkins, Whitney Young, Dorothy Height Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Groups Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), National Urban League (NUL), Negro American Labor Council (NALC) The 1963 March on Washington was one of the most visible and influential Some 250,000 people were present for the March Events events of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther on Washington. They marched from the Washington King Jr. -

©2012 Christopher Hayes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

2012 Christopher Hayes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE HEART OF THE CITY: CIVIL RIGHTS, RESISTANCE AND POLICE REFORM IN NEW YORK CITY, 1945-1966 by CHRISTOPHER HAYES A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Dr. Mia Bay New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION THE HEART OF THE CITY: CIVIL RIGHTS, RESISTANCE AND POLICE REFORM IN NEW YORK CITY, 1945-1966 By CHRISTOPHER HAYES Dissertation Director: Dr. Mia Bay This dissertation uses New York City’s July 1964 rebellions in Central Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant to explore issues of civil rights, liberalism, policing and electoral politics in New York City between 1945 and 1966. The city’s rebellions, the first of the 1960s urban uprisings that would come to define the decade, had widespread repercussions and shaped political campaigns at the local, state and national levels. Looking both backward and forward from the rebellions, I examine the causes many observers gave for the rebellions as well as what outcomes the uprisings had. Using archival records, government documents, newspapers and correspondence between activists and city officials, I look at the social and economic conditions in which black New Yorkers lived during the postwar period, the various ways in which black citizens and their white allies tried to remedy pervasive segregation and its deleterious effects, and the results of those attempts at reform. In providing a previously unavailable narrative of the nearly weeklong July rebellions, I show the ways in which the city’s black citizens expressed their frustrations with city officials, the police and local black ii leaders and how each group responded. -

"Slow Dance on the Killing Ground": the Willie Francis Case Revisited

DePaul Law Review Volume 32 Issue 1 Fall 1982 Article 2 "Slow Dance on the Killing Ground": The Willie Francis Case Revisited Arthur S. Miller Jeffrey H. Bowman Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Arthur S. Miller & Jeffrey H. Bowman, "Slow Dance on the Killing Ground": The Willie Francis Case Revisited, 32 DePaul L. Rev. 1 (1982) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol32/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "SLOW DANCE ON THE KILLING GROUND":t THE WILLIE FRANCIS CASE REVISITED tt Arthur S. Miller* and Jeffrey H. Bowman** The time is past in the history of the world when any living man or body of men can be set on a pedestal and decorated with a halo. FELIX FRANKFURTER*** The time is 1946. The place: rural Louisiana. A slim black teenager named Willie Francis was nervous. Understandably so. The State of Louisiana was getting ready to kill him by causing a current of electricity to pass through his shackled body. Strapped in a portable electric chair, a hood was placed over his head, and the electric chair attendant threw the switch, saying in a harsh voice "Goodbye, Willie." The chair didn't work properly; the port- able generator failed to provide enough voltage. Electricity passed through Willie's body, but not enough to kill him. -

60459NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov.1 1 ------------------------ 51st Edition 1 ,.' Register . ' '-"978 1 of the U.S. 1 Department 1 of Justice 1 and the 1 Federal 1 Courts 1 1 1 1 1 ...... 1 1 1 1 ~~: .~ 1 1 1 1 1 ~'(.:,.:: ........=w,~; ." ..........~ ...... ~ ,.... ........w .. ~=,~~~~~~~;;;;;;::;:;::::~~~~ ........... ·... w.,... ....... ........ .:::" "'~':~:':::::"::'«::"~'"""">X"10_'.. \" 1 1 1 .... 1 .:.: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 .:~.:.:. .'.,------ Register ~JLst~ition of the U.S. JL978 Department of Justice and the Federal Courts NCJRS AUG 2 1979 ACQlJ1SfTIOI\fS Issued by the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 'U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1978 51st Edition For sale by the Superintendent 01 Documents, U.S, Government Printing Office WBShlngton, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 027-ootl-00631Hl Contents Par' Page 1. PRINCIPAL OFFICERFI OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 1 II. ADMINISTRATIV.1ll OFFICE Ul"ITED STATES COURTS; FEDERAL JUDICIAL CENTER. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 19 III. THE FEDERAL JUDICIARY; UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS AND MARSHALS. • • • • • • • 23 IV. FEDERAL CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTIONS 107 V. ApPENDIX • • • • • • • • • • • • • 113 Administrative Office of the United States Courts 21 Antitrust Division . 4 Associate Attorney General, Office of the 3 Attorney General, Office of the. 3 Bureau of Prisons . 17 Civil Division . 5 Civil Rights Division . 6 Community Relations Service 9 Courts of Appeals . 26 Court of Claims . '.' 33 Court of Customs and Patent Appeals 33 Criminal Division . 7 Customs Court. 33 Deputy Attorney General, Offico of. the 3 Distriot Courts, United States Attorneys and Marshals, by districts 34 Drug Enforcement Administration 10 Federal Bureau of Investigation 12 Federal Correctional Institutions 107 Federal Judicial Center • . -

Rep. Bass Elected to Chair House Subcommittee on Africa, Global

Rep. Bass Elected To Chair House Subcommittee On Africa, Global Jan Perry Declares Candidacy Health, Global Human Rights and for Los Angeles County Supervi- International Organizations sor (See page A-2) (See page A-14) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12 - 18, 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO. 05, $1.00 +CA. Sales “ForTax Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years TheYears Voice The Voiceof Our of Community Our Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself” THURSDAY, JANUARY 31, 2019 BY NIELE ANDERSON Staff Writer James Ingram’s musi- cal career will forever be carved in the Grammy ar- chives and Billboard 100 charts. His rich and soulful vocals ruled the R&B and Pop charts in the 80’s and 90’s. Ingram was discov- ered by Quincy Jones on a demo for the hit, Just Once, written by Barry Mann and FILE PHOTO Cynthia Weil, which he sang for $50. STAFF REPORT investigation regarding He went on to record the Los Angeles Police hits, “Just Once,” “One Long before the 2015 Department’s Metropoli- Hundred Ways,” “How Sandra Bland traffic stop tan Division and the in- Do You Keep the Music in Houston, Texas, Afri- creasing number of stops Playing?” and “Yah Mo can Americans have been officers have made on Af- B There,” a duet with Mi- battling with the reoccur- rican American motorists. chael McDonald. One of ring fear of driving while According to the re- his milestone writing cred- Black. Some people be- port, “Nearly half the driv- its was with Quincy Jones lieve that the fear of driv- ers stopped by Metro are on Michael Jackson’s 1983 ing while Black, is associ- Black, which has helped Top 10 hit “P.Y.T.” (Pretty ated with a combination drive up the share of Afri- Young Thing).