Discourses of Film Terrorism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

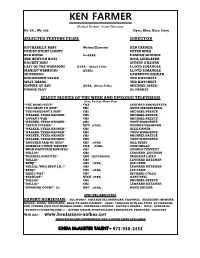

K E N F a R M

KEN FAR MER (Partial Resume- Actor/Director) Ht: 6ft., Wt: 200 Eyes: Blue, Hair: Grey SELECTED FEATURE FILMS DIRECTOR ROCKABILLY BABY Writer/Director KEN FARMER FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS PETER BERG RED RIDGE Co-STAR DAMIAN SKINNER THE NEWTON BOYS RICK LINKLATER ROCKET MAN STUART GILLARD LAST OF THE WARRIORS (STAR, - Above Title) LLOYD SIMANDLE MANIAC WARRIORS (STAR) LLOYD SIMANDLE SILVERADO LAWRENCE KASDAN UNCOMMON VALOR TED KOTCHEFF SPLIT IMAGE TED KOTCHEFF EMPIRE OF ASH (STAR - Above Title) MICHAEL MAZO POWER PLAY AL FRAKES SELECT MOVIES OF THE WEEK AND EPISODIC TELEVISION (Star, Co-Star, Guest Star) “THE GOOD GUYS” FOX SANFORD BOOKSTAVER "TOO LEGIT TO QUIT" VH1 ARTIE MANDELBERG "THE PRESIDENT'S MAN" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "LOGAN'S WAR" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "AUSTIN STORIES" MTV (STAR) GEORGE VERSHOOR "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS ALEX SINGER "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "ANOTHER PAIR OF ACES" CBS (STAR) BILL BIXBY "AMERICA'S MOST WANTED" FOX (STAR) TOM SHELLY "HIGH MOUNTAIN RANGERS" CBS GEORGE FENNEDY "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "GENERAL HOSPITAL" ABC (RECURRING) MARLENA LAIRD "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "BENJI" CBS (STAR) JOE CAMP "DALLAS, WHO SHOT J.R.?" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "BENJI" CBS (STAR) JOE CAMP "JAKE'S WAY" CBS RICHARD COLLA "BACKLOT" NICK (STAR) GARY PAUL "DALLAS" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "SUPERIOR COURT" (2) NBC (STAR) HANK GRIMER SPECIAL ABILITIES EXPERT HORSEMAN: ALL SPORTS: COLLEGE ALL-AMERICAN, FOOTBALL: EXCELLENT SWIMMER: DIVING: SCUBA: WRESTLING: HAND-TO-HAND COMBAT: USMC: FAMILIAR WITH ALL TYPES OF FIREARMS: CAN FURNISH OWN FILM TRAINED HORSE: BACHELOR'S DEGREE - SPEECH & DRAMA : GOLF: AUTHOR OF "ACTING IS STORYTELLING ©" : ACTING COACH: STORYTELLING CONSULTANT: PRODUCER: DIRECTOR Web Site - www.kenfarmer-author.net THEATRICAL AND COMMERCIAL DVD & AUDIO TAPES AVAILABLE LINDA McALISTER TALENT - 972-938-2433. -

Tuesday Nights with Stafford Film Theatre at the Gatehouse Spring

14 Apr Bait Mark Jenkin / UK 2019 / 89 min / Cert 15 Spring Season 2020 11 Feb Official Secrets Tensions simmer between locals and tourists in a Cornish fishing 18 Feb Pain and Glory village in this authentic and arrestingly strange tale. Struggling 25 Feb Sorry We Missed You fisherman Martin has personal reason for resentment, forced to sell his parents’ harbour-front cottage to a wealthy city-dwelling 3 Mar The Farewell family who arrive for their summer holiday. And then Martin's van 10 Mar Knives Out is clamped…Bait’s unique visual style, shot in glitchy 17 Mar Honeyland monochrome on a vintage 16mm cine-camera, with crudely 24 Mar Dirty God over-dubbed dialogue and sound effects, give it the feel of a recently exhumed 70 year-old artefact. Tough yet funny and 31 Mar Monos poignant, Mark Kermode called it “One of the defining British films 7 Apr Woman at War of the decade.” You won’t have seen anything quite like it before. 14 Apr Bait 21 Apr Parasite 5 May So Long My Son 21 Apr Parasite Bong Joon-ho / South Korea 2019 / 132 min / Cert 15 / Subtitles All films are screened at the Gatehouse Theatre, Tuesday nights with Eastgate Street Stafford ST16 2LT. Our programme Winner of the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival this South starts at 7.30pm with the main feature at 7.45pm. Korean black comedy thriller has many twists and turns. The Kim Stafford Film Theatre at family of fraudsters lie their way into working closely with the Park family, the picture of aspirational wealth. -

The Construction of Muslim Terrorism in the Kingdom Movie (2007) Directed by Peter Berg: a Reception Theory Magister of Language

THE CONSTRUCTION OF MUSLIM TERRORISM IN THE KINGDOM MOVIE (2007) DIRECTED BY PETER BERG: A RECEPTION THEORY PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Master Degree of Education in Magister of Language Study by: Agung Budi Santoso S200130035 MAGISTER OF LANGUAGE STUDY MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2015 i ii iii 1 THE CONSTRUCTION OF MUSLIM TERRORISM IN THE KINGDOM MOVIE (2007) DIRECTED BY PETER BERG: A RECEPTION THEORY Agung Budi Santoso Magister of Language Study Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta Abstract This study belongs to the literary study. This study analyzes the construction of Muslim terrorism based on reader response reflected in The Kingdom Movie (2007). There are two objectives of the study, the first is to describe the dominant issues by the reviewers in applying reader response theory to Peter Berg‟s The Kingdom movie, and the second is to explain the reason why the dominant issue are perceived differently by reviewers. This study is a qualitative study and using two data sources; they are primary and secondary data. The primary data source is the reviews of The Kingdom movie (2007) by Peter Berg from IMDb (Internet Movie Database). The secondary data of this study are taken from other sources such as literary book, previous studies, articles, journals, and also website related to reader response theory. This study aimed to reveal how the cultural reader response reflected to The Kingdom movie. The dominant issue which is respond by the reviewers is the terrorism dealing with the culture reader response. Keywords: Culture Reader Response, Richard Beach, The Kingdom Abstrak Penelitian ini termasuk dalam penelitian sastra. -

American Society

AMERICAN SOCIETY Prepared By Ner Le’Elef AMERICAN SOCIETY Prepared by Ner LeElef Publication date 04 November 2007 Permission is granted to reproduce in part or in whole. Profits may not be gained from any such reproductions. This book is updated with each edition and is produced several times a year. Other Ner LeElef Booklets currently available: BOOK OF QUOTATIONS EVOLUTION HILCHOS MASHPIAH HOLOCAUST JEWISH MEDICAL ETHICS JEWISH RESOURCES LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT ORAL LAW PROOFS QUESTION & ANSWERS SCIENCE AND JUDAISM SOURCES SUFFERING THE CHOSEN PEOPLE THIS WORLD & THE NEXT WOMEN’S ISSUES (Book One) WOMEN’S ISSUES (Book Two) For information on how to order additional booklets, please contact: Ner Le’Elef P.O. Box 14503 Jewish quarter, Old City, Jerusalem, 91145 E-mail: [email protected] Fax #: 972-02-653-6229 Tel #: 972-02-651-0825 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: PRINCIPLES AND CORE VALUES 5 i- Introduction 6 ii- Underlying ethical principles 10 iii- Do not do what is hateful – The Harm Principle 12 iv- Basic human rights; democracy 14 v- Equality 16 vi- Absolute equality is discriminatory 18 vii- Rights and duties 20 viii- Tolerance – relative morality 22 ix- Freedom and immaturity 32 x- Capitalism – The Great American Dream 38 a- Globalization 40 b- The Great American Dream 40 xi- Protection, litigation and victimization 42 xii- Secular Humanism/reason/Western intellectuals 44 CHAPTER TWO: SOCIETY AND LIFESTYLE 54 i- Materialism 55 ii- Religion 63 a- How religious is America? 63 b- Separation of church and state: government -

William A. Seiter ATTORI

A.A. Criminale cercasi Dear Brat USA 1951 REGIA: William A. Seiter ATTORI: Mona Freeman; Billy DeWolfe; Edward Arnold; Lyle Bettger A cavallo della tigre It. 1961 REGIA: Luigi Comencini ATTORI: Nino Manfredi; Mario Adorf; Gian Maria Volont*; Valeria Moriconi; Raymond Bussires L'agente speciale Mackintosh The Mackintosh Man USA 1973 REGIA: John Huston ATTORI: Paul Newman; Dominique Sanda; James Mason; Harry Andrews; Ian Bannen Le ali della libert^ The Shawshank Redemption USA 1994 REGIA: Frank Darabont ATTORI: Tim Robbins; Morgan Freeman; James Whitmore; Clancy Brown; Bob Gunton Un alibi troppo perfetto Two Way Stretch GB 1960 REGIA: Robert Day ATTORI: Peter Sellers; Wilfrid Hyde-White; Lionel Jeffries All'ultimo secondo Outlaw Blues USA 1977 REGIA: Richard T. Heffron ATTORI: Peter Fonda; Susan Saint James; John Crawford A me la libert^ A nous la libert* Fr. 1931 REGIA: Ren* Clair ATTORI: Raymond Cordy; Henri Marchand; Paul Olivier; Rolla France; Andr* Michaud American History X USA 1999 REGIA: Tony Kaye ATTORI: Edward Norton; Edward Furlong; Stacy Keach; Avery Brooks; Elliott Gould Gli ammutinati di Sing Sing Within These Walls USA 1945 REGIA: Bruce H. Humberstone ATTORI: Thomas Mitchell; Mary Anderson; Edward Ryan Amore Szerelem Ung. 1970 REGIA: K‡roly Makk ATTORI: Lili Darvas; Mari T*r*csik; Iv‡n Darvas; Erzsi Orsolya Angelo bianco It. 1955 REGIA: Raffaello Matarazzo ATTORI: Amedeo Nazzari; Yvonne Sanson; Enrica Dyrell; Alberto Farnese; Philippe Hersent L'angelo della morte Brother John USA 1971 REGIA: James Goldstone ATTORI: Sidney Poitier; Will Geer; Bradford Dillman; Beverly Todd L'angolo rosso Red Corner USA 1998 REGIA: Jon Avnet ATTORI: Richard Gere; Bai Ling; Bradley Whitford; Peter Donat; Tzi Ma; Richard Venture Anni di piombo Die bleierne Zeit RFT 1981 REGIA: Margarethe von Trotta ATTORI: Jutta Lampe; Barbara Sukowa; RŸdiger Vogler Anni facili It. -

Re-Examining Discourses of Muslim Terrorism in Hollywood Beyond

Reid • 95 Te Age of Sympathy: Re-examining discourses of Muslim terrorism in Hollywood beyond the ‘pre-’ and ‘post-9/11’ dichotomy Jay Reid – University of Adelaide [email protected] Te events of September 11 did not herald a new age of terrorism, for terrorism had been primarily fuelled by religion since the 1980s; however, the 9/11 attacks did herald changes in the representation of terrorism in Hollywood cinema, with an increased frequency of Muslim antagonists, more sinister and deadly than their pre-9/11 compatriots. While pre- and post-9/11 images have been investigated in previous studies, the continued evolution of Middle Eastern characters in the decade since the attacks has rarely been discussed. Tis paper examines six Hollywood action flms released between 1991 and 2011 (a decade prior to and after the attacks) through an Orientalism critique, investigating how representations of Muslim terrorists in Western popular culture have evolved. Te fndings support earlier research on a discursive shift immediately post-9/11, but also reveal a second shift in representation, occurring approximately half a decade after the attacks. Cinematic representations immediately after the attacks positioned Muslim terrorists as sympathetic individuals seduced to commit acts of terrorism by religious fundamentalism. However, from 2007 onwards, representations again change, framing onscreen Muslim terrorists as willing participants in violent activities motivated by Islamic fundamentalism, with an absence of the earlier sympathetic positioning. Tis research builds on existing studies into cinematic representations of terrorism and extends our knowledge of the cinematic discourses of the Hollywood Muslim terrorist, a subject to which continued media and public attention is directed. -

UNIVERSITY of Southern CALIFORNIA 11 Jan

UNIVERSAL CITY STUDIOS. INC. AN MCA INC. COMPANY r November 15, 1971 Dr. Bernard _R. Kantor, Chairman Division of Cinema University <;:>f S.outhern California University Park Los Angeles, Calif. 90007 Dear Dr. Kantor: Forgive my delay in answering your nice letter and I want to assure you I am very thrilled about being so honored by the Delta Kappa Al ha, and I most certainly will be present at the . anquet on February 6th. Cordia ~ l I ' Edi ~'h EH:mp 100 UNIVERSAL CITY PLAZA • UNIVERSAL CITY, CALIFORNIA 91608 • 985-4321 CONSOLIDATED FILM I DU TRIES 959 North Seward Street • Hollywood, California 90038 I (213) 462 3161 telu 06 74257 1 ubte eddr n CONSOLFILM SIDNEY P SOLOW February 15, 1972 President 1r. David Fertik President, DKA Uni ersity of Southern California Cinema Department Los Angels, California 90007 Dear Dave: This is to let you know how grateful I am to K for electing me to honorary membership. This is an honor, I must confess, that I ha e for many years dar d to hope that I would someday receive. So ;ou have made a dre m c me true. 'I he award and he widespread publici : th· t it achieved brought me many letters and phone calls of congra ulations . I have enjoyel teaching thee last twent, -four years in the Cinema Department. It is a boost to one's self-rep ct to be accepted b: youn , intelligent people --e peciall, those who are intere.ted in film-m·king . Please e t nJ my thanks to all t e ho ~ere responsible for selec ing me for honor ry~ m er_hip. -

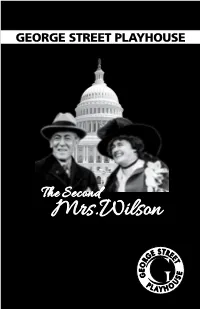

View the Playbill

GEORGE STREET PLAYHOUSE The Second Mrs.Wilson Board of Trustees Chairman: James N. Heston* President: Dr. Penelope Lattimer* First Vice President: Lucy Hughes* Second Vice President: Janice Stolar* Treasurer: David Fasanella* Secretary: Sharon Karmazin* Ronald Bleich David Saint* David Capodanno Jocelyn Schwartzman Kenneth M. Fisher Lora Tremayne William R. Hagaman, Jr. Stephen M. Vajtay Norman Politziner Alan W. Voorhees Kelly Ryman* *Denotes Members of the Executive Committee Trustees Emeritus Robert L. Bramson Cody P. Eckert Clarence E. Lockett Al D’Augusta Peter Goldberg Anthony L. Marchetta George Wolansky, Jr. Honorary Board of Trustees Thomas H. Kean Eric Krebs Honorary Memoriam Maurice Aaron∆ Arthur Laurents∆ Dr. Edward Bloustein∆ Richard Sellars∆ Dora Center∆∆ Barbara Voorhees∆∆ Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.∆ Edward K. Zuckerman∆ Milton Goldman∆ Adelaide M. Zagoren John Hila ∆∆ – Denotes Trustee Emeritus ∆ – Denotes Honorary Trustee From the Artistic Director It is a pleasure to welcome back playwright Joe DiPietro for his fifth premiere here at George Street Playhouse! I am truly astonished at the breadth of his talent! From the wild farce of The Toxic Photo by: Frank Wojciechowski Avenger to the drama of Creating Claire and the comic/drama of Clever Little Lies, David Saint Artistic Director now running at the West Side Theatre in Manhattan, he explores all genres. And now the sensational historical romance of The Second Mrs.Wilson. The extremely gifted Artistic Director of Long Wharf Theatre, Gordon Edelstein, brings a remarkable company of Tony Award-winning actors, the top rank of actors working in American theatre today, to breathe astonishing life into these characters from a little known chapter of American history. -

Malcolm's Video Collection

Malcolm's Video Collection Movie Title Type Format 007 A View to a Kill Action VHS 007 A View To A Kill Action DVD 007 Casino Royale Action Blu-ray 007 Casino Royale Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action Blu-ray 007 Die Another Day Action DVD 007 Die Another Day Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No Action VHS 007 Dr. No Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No DVD Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action Blu-ray 007 From Russia With Love DVD Action DVD 007 Golden Eye (2 copies) Action VHS 007 Goldeneye Action Blu-ray 007 GoldFinger Action Blu-ray 007 Goldfinger Action VHS 007 Goldfinger DVD Action DVD 007 License to Kill Action VHS 007 License To Kill Action Blu-ray 007 Live And Let Die Action DVD 007 Never Say Never Again Action VHS 007 Never Say Never Again Action DVD 007 Octopussy Action VHS Saturday, March 13, 2021 Page 1 of 82 Movie Title Type Format 007 Octopussy Action DVD 007 On Her Majesty's Secret Service Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action Blu-ray 007 Skyfall Action Blu-ray 007 SkyFall Action Blu-ray 007 Spectre Action Blu-ray 007 The Living Daylights Action VHS 007 The Living Daylights Action Blu-ray 007 The Man With The Golden Gun Action DVD 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action Blu-ray 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action VHS 007 The World Is Not Enough Action Blu-ray 007 The World is Not Enough Action DVD 007 Thunderball Action Blu-ray 007 -

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

Nick Davis Film Discussion Group December 2015

Nick Davis Film Discussion Group December 2015 Spotlight (dir. Thomas McCarthy, 2015) On Camera Spotlight Team Robby Robinson Michael Keaton: Mr. Mom (83), Beetlejuice (88), Birdman (14) Mike Rezendes Mark Ruffalo: You Can Count on Me (00), The Kids Are All Right (10) Sacha Pfeiffer Rachel McAdams: Mean Girls (04), The Notebook (04), Southpaw (15) Matt Carroll Brian d’Arcy James: mostly Broadway: Shrek (08), Something Rotten (15) At the Globe Marty Baron Liev Schreiber: A Walk on the Moon (99), The Manchurian Candidate (04) Ben Bradlee, Jr. John Slattery: The Station Agent (03), Bluebird (13), TV’s Mad Men (07-15) The Lawyers Mitchell Garabedian Stanley Tucci: Big Night (96), The Devil Wears Prada (06), Julie & Julia (09) Eric Macleish Billy Crudup: Jesus’ Son (99), Almost Famous (00), Waking the Dead (00) Jim Sullivan Jamey Sheridan: The Ice Storm (97), Syriana (05), TV’s Homeland (11-12) The Victims Phil Saviano (SNAP) Neal Huff: The Wedding Banquet (93), TV’s Show Me a Hero (15) Joe Crowley Michael Cyril Creighton: Star and writer of web series Jack in a Box (09-12) Patrick McSorley Jimmy LeBlanc: Gone Baby Gone (07), and that’s his only other credit! Off Camera Director-Writer Tom McCarthy: See below; co-wrote Pixar’s Up (09), frequently acts Co-Screenwriter Josh Singer: writer, West Wing (05-06), producer, Law & Order: SVU (07-08) Cinematography Masanobu Takayanagi: Silver Linings Playbook (12), Black Mass (15) Original Score Howard Shore: The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (01-03), nearly 100 credits Previous features from writer-director