Japan: Three Epochs of Modern Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning from Japan? Interpretations of Honda Motors by Strategic Management Theorists

Are cross-shareholdings of Japanese corporations dissolving? Evolution and implications MITSUAKI OKABE NISSAN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES NO. 33 2001 NISSAN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES FULL LIST OF PAST PAPERS No.1 Yamanouchi Hisaaki, Oe Kenzaburô and Contemporary Japanese Literature. No.2 Ishida Takeshi, The Introduction of Western Political concepts into Japan. No.3 Sandra Wilson, Pro-Western Intellectuals and the Manchurian Crisis. No.4 Asahi Jôji, A New Conception of Technology Education in Japan. No.5 R John Pritchard, An Overview of the Historical Importance of the Tokyo War Trial. No.6 Sir Sydney Giffard, Change in Japan. No.7 Ishida Hiroshi, Class Structure and Status Hierarchies in Contemporary Japan. No.8 Ishida Hiroshi, Robert Erikson and John H Goldthorpe, Intergenerational Class Mobility in Post-War Japan. No.9 Peter Dale, The Myth of Japanese Uniqueness Revisited. No.10 Abe Shirô, Political Consciousness of Trade Union Members in Japan. No.11 Roger Goodman, Who’s Looking at Whom? Japanese, South Korean and English Educational Reform in Comparative Perspective. No.12 Hugh Richardson, EC-Japan Relations - After Adolescence. No.13 Sir Hugh Cortazzi, British Influence in Japan Since the End of the Occupation (1952-1984). No.14 David Williams, Reporting the Death of the Emperor Showa. No.15 Susan Napier, The Logic of Inversion: Twentieth Century Japanese Utopias. No.16 Alice Lam, Women and Equal Employment Opportunities in Japan. No.17 Ian Reader, Sendatsu and the Development of Contemporary Japanese Pilgrimage. No.18 Watanabe Osamu, Nakasone Yasuhiro and Post-War Conservative Politics: An Historical Interpretation. No.19 Hirota Teruyuki, Marriage, Education and Social Mobility in a Former Samurai Society after the Meiji Restoration. -

The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces' and Indonesia's

The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee Friederike Trotier To cite this article: Friederike Trotier (2017): The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee, The International Journal of the History of Sport, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 Published online: 22 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fhsp20 Download by: [93.198.244.140] Date: 22 February 2017, At: 10:11 THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF SPORT, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee Friederike Trotier Department of Southeast Asian Studies, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO) often serve as Indonesia; GANEFO; Asian an example of the entanglement of sport, Cold War politics and the games; Southeast Asian Non-Aligned Movement in the 1960s. Indonesia as the initiator plays games; International a salient role in the research on this challenge for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Olympic Committee (IOC). The legacy of GANEFO and Indonesia’s further relationship with the IOC, however, has not yet drawn proper academic attention. -

From Politics to Lifestyles: Japan in Print, Ii

, , , :c � !�,1--- , .• ..., rv CORN• L'..i-�- '· .. -� ! i 140 U R. ' • f .• ' I �!"', tih.l. i �. !THACA, N. Y 148·:� 3 FROM POLITICS TO LIFESTYLES: JAPAN IN PRINT, II EDITED BY FRANK BALDWIN. China-Japan Program Cornell University Ithaca, New York 14853 TheCornell East Asia Series is publishedby the Cornell University East Asia Program (distinct from Cornell University Press). We publishaffordably priced books on a variety of scholarly topics relating to East Asia as a serviceto the academic communityand the general public. Standing orders, which provide for automatic notificationand invoicing of each title in the series upon publication, are accepted. Ifafter review by internaland externalreaders a manuscript is accepted for publication, it ispublished on the basis of camera-ready copy provided by the volume author. Each author is thus responsible for any necessarycopy-editing and/or manuscript fo1·1natting. Address submissioninquiries to CEAS Editorial Board, East Asia Program, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-7601. Number 42 in the Cornell East Asia Series Online edition copyright© 2007, print edition copyright© 1986 Frank Baldwin. All rights reserved ISSN 1050-2955 (forrnerly 8756-5293) ISBN-13 978-0-939657-42-1 / ISBN-10 0-939657-42-2 CAUTION: Except for brief quotations in a review, no part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form without permission in writing fromthe author. Please address inquiries to Frank Baldwin in care of the East Asia Program, CornellUniversity, 140 Uris Hall, Ithaca, NY14853-7601 ACKNOWL EDGME?-.'TS The articles in this collection were produced by the Translation Service Center in Tokyo, and I am most grateful to the Japan-u.s. -

Off the Beaten Track: Women's Sport in Iran, Please Visit Smallmedia.Org.Uk Table of Contents

OFF THE BEATEN TRACK: WOMEn’s SPORT IN IRAN Islamic women’s sport appears to be a contradiction in terms - at least this is what many in the West believe. … In this respect the portrayal of the development and the current situation of women’s sports in Iran is illuminating for a variety of reasons. It demonstrates both the opportunities and the limits of women in a country in which Islam and sport are not contradictions.1 – Gertrud Pfister – As the London 2012 Olympics approached, issues of women athletes from Muslim majority countries were splashed across the headlines. When the Iranian women’s football team was disqualified from an Olympic qualifying match because their hejab did not conform to the uniform code, Small Media began researching the history, structure and representation of women’s sport in Iran. THIS ZINE PROVIDES A glimpsE INto THE sitUatioN OF womEN’S spoRts IN IRAN AND IRANIAN womEN atHLETES. We feature the Iranian sportswomen who competed in the London 2012 Summer Olympics and Paralympics, and explore how the western media addresses the topic of Muslim women athletes. Of course, we had to ground their stories in context, and before exploring the contemporary situation, we give an overview of women’s sport in Iran in the pre- and post- revolution eras. For more information or to purchase additional copies of Off the Beaten Track: Women's Sport in Iran, please visit smallmedia.org.uk TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Historical Background 5 Early Sporting in Iran 6 The Pahlavi Dynasty and Women’s Sport 6 Women’s Sport -

Multicultural and Multiethnic Education in Japan

Educational Studies in Japan: International Yearbook No.4, December, 2009, pp.53-65 Multicultural and Multiethnic Education in Japan NOMOTO, Hiroyuki* In Japan, the Ainu people have been living mainly in Hokkaido and many Koreans continue to live since the end of the World War Two. Since 1990’s, the number of migrant workers has increased rapidly. In this sence, Japanese soci- ety has been multicultural and multiethnic. However, those minority groups have been strictly discriminated against in Japanese society and in schools, they have not been given opportunities to multicultural and multiethnic education. Against the ignorance of their culture and language, those minority groups established their own schools apart from existing school system to educate their children with pride of their own culture and language. Today those interna- tional and ethnic schools have an important role in providing foreign children with alternative education. Then, those schools have to be supported financially by the Government. The struggle of the Ainu people to establish their own school should be also supported by the Government, since the Ainu people have been recognized as an indigenous people by the Japanese Government. With globalization, the number of foreign students has rapidly increased in public schools. In order to respond to the educational needs of those chil- dren, the educational authorities have begun to provide them with special pro- grams for teaching Japanese as a Second Language (JSL) and with native language instruction. Concerning JSL programs, the period of the program should be extended to more than 5 years. It is too short to develop cognitive/academic language proficiency (CALP). -

The Meiji Restoration

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 ! The Meiji Restoration ! ! ! Chair: Justin Hsuan, [email protected] CoChair: Jiabo Feng Crisis Director: Brooke Mandujano ! ! Dear Delegates, Welcome to this special committee! I hope you are as excited as I am. As you will witness first-hand, the Meiji Restoration was a dramatic turning point in Japan’s history. For that reason, many believe it to be more accurately a revolution. Please first consider the tumultuous environment of the 19th century. This was the age of rapid industrialization. Across the world populations were shifting due to urbanization, factories were displacing farms, and new markets were being created. Hungry for new consumers and the natural resources necessary, newly-industrialized nations sent emissaries overseas to search for new opportunities in foreign lands. Asia became a prime target for Western governments as Europe and the United States made inroads on countries such as India, China, and Japan. Now please consider the state of Japan at this time. Imagine a government being threatened for the first time by a Western power. Imagine an ultimatum signed by the U.S. President threatening military action to enforce open trade between Japan and the West. Imagine the numerous young and patriotic samurai witnessing their beloved nation threatened and helpless to resist. Imagine the rice farmers moving from the villages to the capital city of Edo for the first time to open up shops. Imagine wealthy merchants who still cannot gain the respect of poor peasants and impoverished samurai. I hope that is helpful to attempt to gain the mindset of the people of Japan during this fascinating and chaotic time. -

Distinctive Features of Japanese Education System

Distinctive Features of the Japanese Education System “Thus there is a general belief that a student’s performance in one crucial examination at about the age of 18 is likely to determine the rest of his life. In other words: the university entrance examination is the primary sorting device for careers in Japanese society. The result is not an aristocracy of birth, but a sort of degree-ocracy” (OECD, Reviews of National Policies for Education: JAPAN. 1971 p.89) What are the distinctive features of the Japanese education system? Explaining the characteristics and features of the Japanese education system to readers from other countries is not an easy task. In the process of educational development, Japan modeled its system after the developed countries in the West, and introduced many elements of the school system from those countries. Japan has a well-developed educational system in which the structure and function has much in common with many other industrialized countries. However, it is possible to identify some characteristics that are particular to the Japanese system. In the tradition and culture of Japan, some parts of the education system often function differently from those in other countries. In its social context, some functions of the education system have been excessively exploited, and other functions have been relatively disregarded. At the same time, distinctive features represent both the strengths and weaknesses of the Japanese education system. While with the passage of time some features have changed, other features have remained unchanged for many decades. As a point of departure, we discuss one notable work treating this topic. -

The Influence of Politics and Culture on English Language Education in Japan

The Influence of Politics and Culture on English Language Education in Japan During World War II and the Occupation by Mayumi Ohara Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Production Note: Signature removed prior to publication. Mayumi Ohara 18 June, 2015 i Acknowledgement I owe my longest-standing debt of gratitude to my husband, Koichi Ohara, for his patience and support, and to my families both in Japan and the United States for their constant support and encouragement. Dr. John Buchanan, my principal supervisor, was indeed helpful with valuable suggestions and feedback, along with Dr. Nina Burridge, my alternate supervisor. I am thankful. Appreciation also goes to Charles Wells for his truly generous aid with my English. He tried to find time for me despite his busy schedule with his own work. I am thankful to his wife, Aya, too, for her kind understanding. Grateful acknowledgement is also made to the following people: all research participants, the gatekeepers, and my friends who cooperated with me in searching for potential research participants. I would like to dedicate this thesis to the memory of a research participant and my friend, Chizuko. -

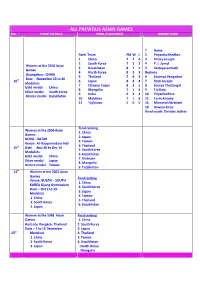

Vb W Previous Ag

ALL PREVIOUS ASIAN GAMES No. EVENT DETAILS FINAL STANDINGS INDIAN TEAM ? Name Rank Team Pld W L 2 Priyanka Khedkar 1 China 7 7 0 3 Princy Joseph 2 South Korea 7 5 2 4 P. J. Jomol Women at the 2010 Asian 3 Kazakhstan 8 7 1 5 Kattuparambath Games 4 North Korea 8 5 3 Reshma Guangzhou - CHINA 5 Thailand 7 4 3 6 Soumya Vengadan Date November 13 to 26 16th 6 Japan 8 4 4 7 Shibi Joseph Medalists 7 Chinese Taipei 8 3 5 8 Soorya Thottangal Gold medal China 8 Mongolia 7 1 6 9 Tiji Raju Silver medal South Korea 9 India 6 2 4 10 Priyanka Bora Bronze medal Kazakhstan 10 Maldives 7 1 6 12 Terin Antony 11 Tajikistan 5 0 5 16 Minomol Abraham 18 Aswani Kiran Head coach: Devidas Jadhav Final ranking Women at the 2006 Asian 1. China Games 2. Japan DOHA - QATAR 3. Taiwan Venue Al-Rayyan Indoor Hall 4. Thailand 15th Date Nov 26 to Dec 14 5. South Korea Medalists 6. Kazakhstan Gold medal China 7. Vietnam Silver medal Japan 8. Mongolia Bronze medal Taiwan 9. Tadjikistan 14th Women at the 2002 Asian Games Final ranking Venue: BUSAN – SOUTH 1. China KOREA Gijang Gymnasium 2. South Korea Date :- Oct 2 to 13 3. Japan Medalists 4. Taiwan 1 China 5. Thailand 2 South Korea 6. Kazakhstan 3 Japan Women at the 1998 Asian Final ranking Games 1. China Host city Bangkok, Thailand 2. South Korea Date :- 7 to 15 December 3. Japan 13th Medalists 4. -

Author Abstract

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 275 620 SO 017 832 AUTHOR Leestma, Robert; Bennett, William J.; And Others TITLE Japanese Education Today. A Report from the U.S. Study of Education in Japan. Prepared by a Special Task Force of the OERI Japan Study Team: Robert Leestma, Director.., and with an epilogue, "Implications for American Education," by William J. Bennett, Secretary of Education. INSTITUTION Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE Jan 87 NOTE 103p.; Other Task Force members: Robert L. August, Betty George, Lois Peak. Other contributors: Nobuo Shimahara, William K. Cummings, Nevner G. Stacey. Editor: Cynthia Hearn Dorfman. For related documents, see SO 017 443-460. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Asian Studies; Comparative Education; Educetion; Educational Change; *Elementary School Curriculum; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Japanese; *Secondary School Curriculum; Teacher Education IDENTIFIERS *Japan ABSTRACT Based on 2 years of research, this comprehensive report of education in Japan is matched by a simultaneously-released counterpart Japanese study of education in the United States. Impressive accomplishments of the Japanese systemare described. For example, nearly everyone completes a rigorouscore curriculum during 9 compulsory years of schooling, about 90 percent of the students graduate from high school, academic achievement tends to be high, and schools contribute substantially to national economic strength. Reasons for Japanese successes include: clear purposes rooted deeply in the culture, well-defined and challenging curricula, well-ordered learning environments, high expectations for student achievement, strong motivation and effective study habits of students, extensive family involvement in the mission of schools, and highstatus of teachers. -

Download English

www.smartkeeda.com | h ttps://testzone.smartkeeda.com/# SBI | RBI | IBPS |RRB | SSC | NIACL | EPFO | UGC NET |LIC | Railways | CLAT | RJS Join us Testzone presents Full-Length Current Affairs Mock Test Series Month-wise April MockDrill100 PDF No. 4 (PDF in English) Test Launch Date: 2nd May 2021 Attempt Test No 4 Now! www.smartkeeda.com | h ttps://testzone.smartkeeda.com/# SBI | RBI | IBPS |RRB | SSC | NIACL | EPFO | UGC NET |LIC | Railways | CLAT | RJS Join us An important message from Team Smartkeeda Hi Folks! We hope you all are doing well. We would like to state here that this PDF is meant for preparing for the upcoming MockDrill Test of April 2021 Month at Testzone. In this Current Affairs PDF we have added all the important Current Affairs information in form of ‘Key-points’ which are crucial if you want to score a high rank in Current Affairs Mocks at Testzone. Therefore, we urge you to go through each piece of information carefully and try to remember the facts and figures because the questions to be asked in the Current Affairs MockDrill will be based on the information given in the PDF only. We hope you will make the best of use of this PDF and perform well in MockDrill Tests at Testzone. All the best! Regards Team Smartkeeda मा셍टकीड़ा 셍ीम की ओर से एक मह配वपू셍 ट सꅍदेश! मित्रⴂ! हि आशा करते हℂ की आप सभी वथ और कु शल हⴂगे। इस सन्देश के िाध्यि से हि आपसे यह कहना चाहते हℂ की ये PDF अप्रैल 2021 िाह िᴂ Testzone पर होने वाले MockDrill Test िᴂ आपकी तैयारी को बेहतर करने के मलए उपल녍ध करायी जा रही है। इस PDF िᴂ हिने कु छ अतत आव�यक ‘Key-Points’ -

Developing a Football Basic Techniques Learning Model Through Global Analytical Global Approach

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 464 Proceedings of the 1st Progress in Social Science, Humanities and Education Research Symposium (PSSHERS 2019) Developing a Football Basic Techniques Learning Model Through Global Analytical Global Approach Aldo Naza Putra Physical Education, Universitas Islam 45, Bekasi, Indonesia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study aims to develop an exercise model of basic football technical skills through the Global Analytical Global approach for SSB PSTS students aged 6-12 years. Specifically, the objectives of this study are to produce a design model of basic football technique skills through Global Analytical Global approach for students aged 6-12 years and to see whether the model is more effective in improving the basic technical skills of playing football for students aged 6-12 years. This research was conducted on football students of PSTS Club Padang aged 6-12 years. This research used Research and Development (R & D) model proposed by Borg and Gall. Data collection was done by observation and questionnaire to see the validation of the model tested in the field. Based on the results of data analysis that has been carried out, starting from the process of making the initial draft of the model, revision of the initial model, small group trials, large group trials, the results were very satisfying, where football experts and trainers stated that this model had a positive purpose for improving football playing skills. Variations in this model have good quality in improving playing skills to enrich basic motion since this model was designed based on the principle of practice from the easy to the difficult, and the variations of this model are very attractive for students aged 6-12 years.