State Versus Salman Khan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra 2000 #Anupama Chopra #014029970X, 9780140299700 #Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Penguin Books India, 2000 #National Award Winner: 'Best Book On Film' Year 2000 Film Journalist Anupama Chopra Tells The Fascinating Story Of How A Four-Line Idea Grew To Become The Greatest Blockbuster Of Indian Cinema. Starting With The Tricky Process Of Casting, Moving On To The Actual Filming Over Two Years In A Barren, Rocky Landscape, And Finally The First Weeks After The Film'S Release When The Audience Stayed Away And The Trade Declared It A Flop, This Is A Story As Dramatic And Entertaining As Sholay Itself. With The Skill Of A Consummate Storyteller, Anupama Chopra Describes Amitabh Bachchan'S Struggle To Convince The Sippys To Choose Him, An Actor With Ten Flops Behind Him, Over The Flamboyant Shatrughan Sinha; The Last-Minute Confusion Over Dates That Led To Danny Dengzongpa'S Exit From The Fim, Handing The Role Of Gabbar Singh To Amjad Khan; And The Budding Romance Between Hema Malini And Dharmendra During The Shooting That Made The Spot Boys Some Extra Money And Almost Killed Amitabh. file download natuv.pdf UOM:39015042150550 #Dinesh Raheja, Jitendra Kothari #The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema #Motion picture actors and actresses #143 pages #About the Book : - The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema is a unique compendium if biographical profiles of the film world's most significant actors, filmmakers, music #1996 the Performing Arts #Jvd Akhtar, Nasreen Munni Kabir #Talking Films #Conversations on Hindi Cinema with Javed Akhtar #This book features the well-known screenplay writer, lyricist and poet Javed Akhtar in conversation with Nasreen Kabir on his work in Hindi cinema, his life and his poetry. -

LLB5 MERIT LIST 02032021 Deptfinal.Xlsx

STATE COMMON ENTRANCE TEST CELL, MAHARASHTRA STATE, MUMBAI. DIRECTORATE OF HIGHER EDUCATION, PUNE. Candidates who have successfully admitted for CAP Round-1 Is Is HSC HSC First SSC SSC DOB Previous LinguisticT Religious Applicatio Sr No Application No Name Of Candidate Gender Category Candidature Type Is PH Linguistic Religious Is DP Is Orphan CETScore Percentag Language Percentag English (yyyy-mm- Scrutiny officer Remarks Category ype Type n Status Minority Minority e Marks e Marks dd) * 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 1 APP00002137 HARSHI YOGESH BALDOTA F OPEN NULL Maharashtra Type-A No No NULL Yes Jain No No 127 93.84 88 94.6 88 2002-07-13 Approved Approved 2 APP00000111 SHREYA PRAVEEN BOHRA F OPEN NULL Maharashtra Type-A No No NULL Yes Jain No No 127 92.92 86 97.5 90 2002-09-20 Approved Approved 3 APP00005750 JATIN GOYAL M OPEN NULL All India No NULL NULL NULL NULL NULL No 127 90.2 96 84.8 81 2003-03-02 Approved Approved 4 APP00000750 ANUJ RAJESH LAKHOTIYA M OPEN NULL All India No NULL NULL NULL NULL NULL No 126 92.8 93 78.8 74 2002-07-21 Approved Approved 5 APP00003128 SAHIL ARUN AGARWAL M OPEN NULL Maharashtra Type-A No No NULL No NULL No No 126 79.84 74 92.5 88 2002-05-21 Approved Approved 6 APP00001944 MAHAK ARUN AGRAWAL F OPEN NULL All India No NULL NULL NULL NULL NULL No 126 72.6 82 95 95 2001-10-31 Approved Approved 7 APP00001153 LAKSHITA DR GYAN CHAND JAIN JAIN F OPEN NULL All India No NULL NULL NULL NULL NULL No 125 97 96 93.8 97 2002-11-19 Approved Approved 8 APP00003484 SANYA MR RAKESH KATARE KATARE -

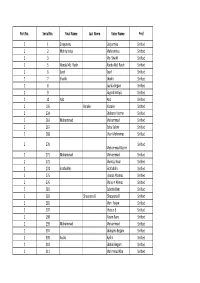

55 Nagpur Central Panchnama List.Xlsx

Part No. Serial No. Final Name Last Name Voter Name Prof 2 1 Sirajunnisa Sirajunnisa Shifted 2 2 Mehrunnisa Mehrunnisa Shifted 2 3 Mo. Sheikh Shifted 2 5 Abeda Md. Raish Abeda Md. Raish Shifted 2 6 Syed Syed Shifted 2 7 Shaikh Shaikh Shifted 2 8 Sayida Begam Shifted 2 9 Sayyad Imtiyaj Shifted 2 10 Aziz Aziz Shifted 2 105 Korake Korake Shifted 2 234 Shabana Yasmin Shifted 2 261 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 267 Babu Salam Shifted 2 268 Khan Mohmmad Shifted 2 270 Shifted Mohammad Bashir 2 271 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 272 Mumtaj Noor Shifted 2 274 Sirafuddin Sirafuddin Shifted 2 275 Isharat Ahamad Shifted 2 276 Maisum Ahmad Shifted 2 281 Zubeda Bano Shifted 2 283 Shaqeena B Shaqeena B Shifted 2 285 Moh. Faijan Shifted 2 297 Khatun B Shifted 2 298 Nasim Bano Shifted 2 299 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 307 Shahjaha Begam Shifted 2 309 Aysha Aysha Shifted 2 310 Shahin Begam Shifted 2 311 Mohmmad Kha Shifted 2 312 Jubeda B Shifted 2 313 Mahajbin Mahajbin Shifted 2 314 Ayyub Ayyub Shifted 2 315 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 316 Yakub Kha Shifted 2 317 Mahbub Kha Shifted 2 318 Sheikh Ilati Shifted 2 325 Kaji Jaibunnisa Shifted 2 326 Kaji Vahid Shifted 2 327 Moh. Aslam Shifted 2 328 Shaheda Begum Shaheda Begum Shifted Mohammad Aslam Mohammad Aslam 2 329 Shirin Bano Shifted 2 330 Mohammad Mohammad Shifted 2 333 Sadeeq Ulla Khan Sadeeq Ulla Khan Shifted Shahnajbano Shahnajbano 2 334 Shifted Sadikaulla Kha Sadikaulla Kha 2 335 Sabeer Ulla Khan Sabeer Ulla Khan Shifted 2 336 Shifted Atiya Kausar Sadeeq Atiya Kausar Sadeeq 2 337 Shifted Ullah Ullah Faridabano Sazid Faridabano Sazid 2 339 Shifted Ahmed Khan Ahmed Khan 2 340 Jabir Akhtar Shifted 2 341 Imran Kha Shifted 2 342 Shifted Shahin Afroz Sadeeq Shahin Afroz Sadeeq 2 346 Jabin Akhtar Jabin Akhtar Shifted 2 347 Raisa Parvin Raisa Parvin Shifted 2 348 Raisa Parvin Raisa Parvin Shifted 2 361 Farida Begam Shifted Nazma Anzum Yunus Nazma Anzum Yunus 2 364 Shifted Khan Khan 2 388 Moh. -

Don – the King Is Back

BS-2485:Berlinale 2012 29.01.2012 13:38 Uhr Seite 90 BERLINALE SPECIAL GALA DON – THE KING IS BACK Farhan Akhtar Don soll sterben. Das beschließt ein europäisches Gangsterkartell. Es Indien/Deutschland 2011 fürchtet den Konkurrenten, der mit günstigen Drogen aus Asien den Länge 140 Min. · Format 35 mm, Cinemascope · Farbe Markt überschwemmen will. Und so hat Don, der sympathische Meis - ter verbrecher, gleich seinen ersten spektakulären Auftritt in Thailand, STABLISTE wo er eine kleine Armee von bis an die Zähne bewaffneten Killern aus - Regie Farhan Akhtar schalten muss. Don, der Held des gleichnamigen Bolly wood-Action- Buch Farhan Akhtar, Javed Akhtar Films DON (Berlinale Forum 2007), rüstet zum Gegen schlag. Es geht Kamera Jason West, Salim Khan um Druckplatten für Euronoten. In Berlin kommt es zum Showdown, Musik Shankar Ehsaan Loy den Don als König der europäischen Unterwelt besteht – nach sensa- Szenenbild Thattam Pokkada Abid tionellen Stunts, betörenden Tanz einla gen und vielen überraschen- Production Design Thomas Hauck BIOGRAFIE Geboren 1974 in Mumbai. Art Director Sidharth Mathawan Karrierebeginn als Regieassistent bei Pankaj den Wendungen. Indiens Superstar Shah Rukh Khan spielt den Supergangster mit viel Kostüm Jamail Odedra, Bettina Helmi Parashar. Anschließend Aufnahmeleiter und Produktionsleitung Philipp Klausing Charme und augenzwinkerndem Humor. Das ganze Leben dieses Regieassistent bei TV-Produktionen, Musik - Produzent Ritesh Sidhwani, Shah Rukh videos und Imagefilmen, Drehbuchautor für Actionhelden ist ein Spiel voller Rasanz. DON ist ein Journal des Luxus Khan, Farhan Akhtar Werbung und Sitcoms. Sein Debütfilm DIL und der Moden, darin James-Bond-Filmen nicht unähnlich. Doch Co-Produzent Mathias Schwerbrock CHAHTA HAI wurde mehrfach ausgezeichnet. -

Manoj Kumar to Be Conferred Dadasaheb Phalke Award for the Year 2015 by : INVC Team Published on : 4 Mar, 2016 09:30 PM IST

Manoj Kumar to be conferred Dadasaheb Phalke Award for the year 2015 By : INVC Team Published On : 4 Mar, 2016 09:30 PM IST INVC NEWS New Delhi, Veteran Film Actor and Director Shri Manoj Kumar is to be conferred the 47th Dadasaheb Phalke Award for the year 2015. Award is conferred by the Government of India for outstanding contribution to the growth and development of Indian Cinema. The Award consists of a Swarn Kamal (Golden Lotus), a cash prize of Rs. 10 lakhs and a shawl. The Award is given on the basis of recommendations of a Committee of eminent personalities set up by the Government for this purpose. This year, a five member jury viz. Latha Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, Salim Khan, Nitin Mukesh and Anup Jalota, unanimously recommended Shri Manoj Kumar for the prestigious Award. Minister for Information & Broadcasting, Shri Arun Jaitley spoke to Shri Manoj Kumar today and congratulated him on being conferred the Award. Shri Manoj Kumar is an Award-winning actor and director. He is remembered for his films Hariyali Aur Raasta, Woh Kaun Thi, Himalaya Ki God Mein, Do Badan, Upkaar, Patthar Ke Sanam, Neel Kamal, Purab Aur Paschim, Roti Kapda Aur Makaan, and Kranti. He is known for acting in and directing films with patriotic themes. Manoj Kumar was born in July 1937, in Abbottabad, then part of Pre- Independent India. When he was 10, he shifted to Delhi. After graduating from Hindu College, University of Delhi, he decided to enter the film industry. After making a début in film Fashion in 1957, Manoj Kumar got his first leading role in Kaanch Ki Gudia in 1960. -

Javed Akhtar - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Javed Akhtar - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Javed Akhtar(17 January 1945 -) Javed Akhtar (Urdu: ????? ????) is a poet, lyricist and scriptwriter from India. Some of his most successful work was done in the late 1970s and 1980s with Salim Khan as half of the script-writing duo credited as Salim-Javed. Akhtar continues to be a prominent figure in Bollywood and is one of the most popular and sought-after lyricists. <b> Early Life </b> He was born as Jadoo Akhtar in Gwalior, (Madhya Pradesh) to Jan Nisar Akhtar, a Bollywood film songwriter and Urdu poet, and singer Safia Akhtar, a teacher and writer. His original name was Jadoo, taken from a line in a poem written by his father: "Lamba, lamba kisi jadoo ka fasana hoga". He was given the official name of Javed since it was the closest to the word jadoo. Amongst his family members who are poets are the Urdu poet Majaz (maternal uncle), and his grandfather, Muztar Khairabadi, and Maulana Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi, a noted philosopher, poet and religious scholar of the nineteenth century. Akhtar's younger brother, Salman Akhtar, is a psychoanalyst practicing in the United States. Having lost his mother while very young, Akhtar's early years were spent in Lucknow, Aligarh and Mumbai, mostly with relatives. He studied in Colvin Taluqdars' College in Lucknow and the Minto Circle where he completed his matriculation from Aligarh Muslim University. After matriculation, Akhtar acquired a B.A. from Saifiya College in Bhopal. A gifted debater in college, he won the Rotary Club Prize frequently. -

Gabbar Singh Gujjar

Gabbar Singh Gujjar How does Gabbar Singh solve all the issues and fights with Siddhappa is crux of the story. Written by sahith. Plot Summary | Add Synopsis. Plot Keywords: police | gang | villain | crazy | revenge | See All (5) ». Genres GABBAR SINGH - Pure entertainer! One man show! Power Star is back with a bang!!! 17 May 2012 | by bharath882005 ⓠSee all my reviews. Pawan Kalyan has given an extraordinary performance. His comedy timing is perfect. He has delivered several punch dialog's with his inimitable mannerism. Gabbar Singh is a fictional character, the antagonist of the 1975 Bollywood film Sholay. Gabbar Singh alias Gabra was born in 1926 in Dang village of Bhind district, a Gujjar by caste. He was written by duo Salim-Javed, consisting of Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar. Played by Amjad Khan, he is depicted in Sholay as a dacoit who leads a group in looting and plundering the villages in the region of Ramgarh. He has a sadistic personality and insists on killing whenever required to continue his status and to Nirbhay Singh Gujjar was probably the last among the big bad dacoits of Chambal. Just like a Bollywood film, the life of this bandit revolved around drinks, women, guns and criminals. He was certainly the Gabbar Singh of the modern times with AK-47 assault rifles, shotguns, bulletproof jackets, night-vision binoculars and mobile phones at his disposal. He was probably the Gabbar Singh who was more of a Robin Hood than a notorious bandit. chambal ke daku sardar gabbar singh ke jivan ki kuch rochak jankari apko is video mai milegi real life story of sardar gabbar singh. -

Actress Juhi Chaturvedi (Piku) and Himanshu Announced Madrid As the Cheerfully Shared Pictures and Selfies on Spain Will Get a Better Idea About Bollywood

2 movie masala BOLLYWOOD INSIDER April 2016 April 2016 BOLLYWOOD INSIDER honor 3 IIFA hollers a “Hola!” Bollywood wins big at National Awards 2016 The Bollywood extravaganza, International Indian Film Academy Tanu Weds Manu Returns (IIFA), is heading to Madrid in Spain this June Baahubali Piku Spain,” he said. The new venue aims to reach out to the huge Latin American market for Indian films. Sonakshi said, “The event AND THE WINNERS ARE... is an excellent opportunity for us to take our cinema across the globe. Madrid is a Best Film Nargis Dutt Award for Best Feature thrilling city, and I am looking forward to Baahubali (Telugu) Film on National Integration experiencing another spectacular IIFA in Nanak Shah Fakir another amazing destination.” Best Director Andre Timmins, director, Wizcraft Sanjay Leela Bhansali (Bajirao Mastani) Indira Gandhi Award for Best Debut International, said, “This year our Best Actor Film (Director) excitement for Spain is strongly focused Amitabh Bachchan (Piku) Neeraj Ghaywan (Masaan) on the opportunity to address CSR and Best Screenplay Writer (Original) izcraft International has regale the crowd on the streets. The actors understand where we come from. By June, environmental issues.” IIFA will celebrate Best Actress Juhi Chaturvedi (Piku) and Himanshu announced Madrid as the cheerfully shared pictures and selfies on Spain will get a better idea about Bollywood. IIFA Rocks Fest; IIFA Stomp, an exhibition Kangana Ranaut (Tanu Weds Manu Returns) Sharma (Tanu Weds Manu Returns) Wofficial host of the 17th their social media accounts, soaking in the And Madrid is such a charming city—with of urban trends; and the magnificent IIFA Best Supporting Actor edition of the IIFA gala from June 23 joie de vivre of the city that is tinted in hues an explosion of sounds, colors and textures Awards. -

Dilip-Kumar-The-Substance-And-The

No book on Hindi cinema has ever been as keenly anticipated as this one …. With many a delightful nugget, The Substance and the Shadow presents a wide-ranging narrative across of plenty of ground … is a gold mine of information. – Saibal Chatterjee, Tehelka The voice that comes through in this intriguingly titled autobiography is measured, evidently calibrated and impossibly calm… – Madhu Jain, India Today Candid and politically correct in equal measure … – Mint, New Delhi An outstanding book on Dilip and his films … – Free Press Journal, Mumbai Hay House Publishers (India) Pvt. Ltd. Muskaan Complex, Plot No.3, B-2 Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110 070, India Hay House Inc., PO Box 5100, Carlsbad, CA 92018-5100, USA Hay House UK, Ltd., Astley House, 33 Notting Hill Gate, London W11 3JQ, UK Hay House Australia Pty Ltd., 18/36 Ralph St., Alexandria NSW 2015, Australia Hay House SA (Pty) Ltd., PO Box 990, Witkoppen 2068, South Africa Hay House Publishing, Ltd., 17/F, One Hysan Ave., Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Raincoast, 9050 Shaughnessy St., Vancouver, BC V6P 6E5, Canada Email: [email protected] www.hayhouse.co.in Copyright © Dilip Kumar 2014 First reprint 2014 Second reprint 2014 The moral right of the author has been asserted. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All photographs used are from the author’s personal collection. All rights reserved. -

2021 Part No

Deolali Cantonment Board Voter List - 2021 Part No. 1 Ward No.4 Sr.No. Name Age Father / Husband Name Address 1 Abesh 55 Khodadad Irani Orient Guest House-360/A 2 Nairika 26 Abesh Irani Orient Guest House-360/A 3 Prazan 24 Abesh Irani Orient Guest House-360/A 4 Radhabai 77 Pandurang Dabhade Orient Guest House-360/A 5 Kamlabai 72 Namdev Adke Parshi Arogyadham Lam Rd 1529 6 Anil 47 Namdev Adke Parshi Arogyadham Lam Rd 1529 7 Savita 40 Anil Adke Parshi Arogyadham Lam Rd 1529 8 Dilip 42 Namdev Adke Parshi Arogyadham Lam Rd 1529 9 Mangal 37 Dilip Adke Parshi Arogyadham Lam Rd 1529 10 Nandu 39 Namdev Adke Parshi Arogyadham Lam Rd 1529 11 Kavita 37 Nandu Adke Parshi Arogyadham Lam Rd 1529 12 Jitendra 49 Surlal Jain GoldCoin 2138 13 Pallavi 43 Jitendra Jain GoldCoin 2138 14 Daniyal 44 Ji Isak GoldCoin 2139 15 Lawriyal 45 Daniyal Isak GoldCoin 2139 16 Eailan 42 Farnandis GoldCoin 2139 17 Ishak 61 Mohamad Efendi GoldCoin 961 18 Almas 52 Mohamad Efendi GoldCoin 961 19 Hussain 27 Ishaq Efendi GoldCoin 961 20 Saniya 25 Ishaq Efendi GoldCoin 961 21 Saleem. 79 Ali Sayyad GoldCoin 961 22 Ferbanu 72 salim sayyad GoldCoin 961 23 Ajay 56 Hemendra Desai H.N.2141, Gold Coin Lam Road 24 Darshana 52 Ajay Desai H.N.2141, Gold Coin Lam Road 25 Nilay 32 Ajay Desai H.N.2141, Gold Coin Lam Road 26 Bhavna 30 Nilay Desai H.N.2141, Gold Coin Lam Road 27 Pol (Pawl) 59 Anthonidas Mariyan H.N.212, Lam Road 28 Joseph 57 Anthonidas Mariyan H.N.2434, Lam Road 29 Denis 47 Anthonidas Mariyan H.N.2434, Lam Road 30 Andrwe 69 Victor Makardo Gold Coin 208 31 Rita 57 Eaindundu -

Indian Film Industry: Tackling Litigations

MUMBAI SILICON VALLEY BANGALORE SINGAPORE MUMBAI BKC NEW DELHI MUNICH NEW YORK Indian Film Industry Tackling Litigations January 2017 © Copyright 2017 Nishith Desai Associates www.nishithdesai.com Indian Film Industry Tackling Litigations About NDA Nishith Desai Associates (NDA) is a research based international law firm with offices in Mumbai, Bangalore, Palo Alto (Silicon Valley), Singapore, New Delhi, Munich and New York. We provide strategic legal, regulatory, and tax advice coupled with industry expertise in an integrated manner. As a firm of specialists, we work with select clients in select verticals on very complex and innovative transactions and disputes. Our forte includes innovation and strategic advice in futuristic areas of law such as those relating to Bitcoins (block chain), Internet of Things (IOT), Aviation, Artificial Intelligence, Privatization of Outer Space, Drones, Robotics, Virtual Reality, Med-Tech, Ed-Tech and Medical Devices and Nanotechnology. We specialize in Globalization, International Tax, Fund Formation, Corporate & M&A, Private Equity & Venture Capital, Intellectual Property, International Litigation and Dispute Resolution; Employment and HR, Intellectual Property, International Commercial Law and Private Client. Our industry expertise spans Automobile, Funds, Financial Services, IT and Telecom, Pharma and Healthcare, Media and Entertainment, Real Estate, Infrastructure and Education. Our key clientele comprise marquee Fortune 500 corporations. Our ability to innovate is endorsed through the numerous accolades gained over the years and we are also commended by industry peers for our inventive excellence that inspires others. NDA was ranked the ‘Most Innovative Asia Pacific Law Firm in 2016’ by the Financial Times - RSG Consulting Group in its prestigious FT Innovative Lawyers Asia-Pacific 2016 Awards. -

Recycle Industry: the Visual Economy of Remakes in Contemporary Bombay Film Culture by Ramna Walia “Audiences Now Want New Stories

Recycle Industry: The Visual Economy of Remakes in Contemporary Bombay Film Culture by Ramna Walia “Audiences now want new stories. The problem is Bollywood has no tradition of producing original screenplays" —Chander Lall, lawyer “The brain is a recycling bin, not a creative bin. What goes in comes out in different ways” —Mahesh Bhatt, filmmaker and producer hus spoke filmmaker and producer Mahesh Bhatt when Mr. Chander Lall, the legal representative of two of Hollywood's major studios issued “warning Tletters” to film producers in Bombay who were poised to “indianize” a series of Hollywood films.1 While Lall referred to Bollywood’s widespread practice of making uncredited remakes of Hollywood films as “tradition,” Bhatt defiantly saw these remakes as a symptom of a larger mechanism of recycling material. In fact, the influence of other cinemas on Bombay films was reflected narratively and in other aspects of filmmaking such as fashion, poster art etc. Thus, at the center of this debate was the issue of Bombay cinema's identity as a bastardized clone of Hollywood and the counter argument that noted the distinctiveness of Bombay film culture by highlighting the “difference” in the manner of production. In view of these unacknowledged networks of exchange, the term “remake” was often used within popular discourse as an underhanded accusation of plagiarism against Bombay films. Moreover, because most of Bombay cinema’s remakes of Hollywood films were un-credited, they never secured the legitimacy attained in Hollywood and world cinemas wherein this process was seen as a reinterpretation of an earlier work or an updated modus operandi.