How to Make a GNU/Linux Kernel Patch? Robert Berger [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enabling Musical Applications on a Linux Phone

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Creative Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 2009 Enabling Musical Applications On A Linux Phone Greg Schiemer University of Wollongong, [email protected] E. Chen Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/creartspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Schiemer, Greg and Chen, E.: Enabling Musical Applications On A Linux Phone 2009. https://ro.uow.edu.au/creartspapers/36 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] ENABLING MUSICAL APPLICATIONS ON A LINUX PHONE Greg Schiemer Eva Cheng Sonic Arts Research Network School of Electrical and Computer Faculty of Creative Arts Engineering University of Wollongong RMIT Melbourne 2522 3000 The prospect of using compiled Arm9 native code of- fers a way to synthesise music using generic music soft- ABSTRACT ware such as Pure data and Csound rather than interpre- tive languages like java and python which have been Over the past decade the mobile phone has evolved to used in mobile devices [1, 2]. A similar approach to mo- become a hardware platform for musical interaction and bile synthesis has been adopted using the Symbian oper- is increasingly being taken seriously by composers and ating system [3]. instrument designers alike. Its gradual evolution has seen The Linux environment is more suited to the devel- improvements in hardware architecture that require al- opment of new applications in embedded hardware than ternative methods of programming. -

Adaptive Android Kernel Live Patching

Adaptive Android Kernel Live Patching Yue Chen Yulong Zhang Zhi Wang Liangzhao Xia Florida State University Baidu X-Lab Florida State University Baidu X-Lab Chenfu Bao Tao Wei Baidu X-Lab Baidu X-Lab Abstract apps contain sensitive personal data, such as bank ac- counts, mobile payments, private messages, and social Android kernel vulnerabilities pose a serious threat to network data. Even TrustZone, widely used as the se- user security and privacy. They allow attackers to take cure keystore and digital rights management in Android, full control over victim devices, install malicious and un- is under serious threat since the compromised kernel en- wanted apps, and maintain persistent control. Unfortu- ables the attacker to inject malicious payloads into Trust- nately, most Android devices are never timely updated Zone [42, 43]. Therefore, Android kernel vulnerabilities to protect their users from kernel exploits. Recent An- pose a serious threat to user privacy and security. droid malware even has built-in kernel exploits to take Tremendous efforts have been put into finding (and ex- advantage of this large window of vulnerability. An ef- ploiting) Android kernel vulnerabilities by both white- fective solution to this problem must be adaptable to lots hat and black-hat researchers, as evidenced by the sig- of (out-of-date) devices, quickly deployable, and secure nificant increase of kernel vulnerabilities disclosed in from misuse. However, the fragmented Android ecosys- Android Security Bulletin [3] in recent years. In ad- tem makes this a complex and challenging task. dition, many kernel vulnerabilities/exploits are publicly To address that, we systematically studied 1;139 An- available but never reported to Google or the vendors, droid kernels and all the recent critical Android ker- let alone patched (e.g., exploits in Android rooting nel vulnerabilities. -

Android Operating System

Software Engineering ISSN: 2229-4007 & ISSN: 2229-4015, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2012, pp.-10-13. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=76 ANDROID OPERATING SYSTEM NIMODIA C. AND DESHMUKH H.R. Babasaheb Naik College of Engineering, Pusad, MS, India. *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected], [email protected] Received: February 21, 2012; Accepted: March 15, 2012 Abstract- Android is a software stack for mobile devices that includes an operating system, middleware and key applications. Android, an open source mobile device platform based on the Linux operating system. It has application Framework,enhanced graphics, integrated web browser, relational database, media support, LibWebCore web browser, wide variety of connectivity and much more applications. Android relies on Linux version 2.6 for core system services such as security, memory management, process management, network stack, and driver model. Architecture of Android consist of Applications. Linux kernel, libraries, application framework, Android Runtime. All applications are written using the Java programming language. Android mobile phone platform is going to be more secure than Apple’s iPhone or any other device in the long run. Keywords- 3G, Dalvik Virtual Machine, EGPRS, LiMo, Open Handset Alliance, SQLite, WCDMA/HSUPA Citation: Nimodia C. and Deshmukh H.R. (2012) Android Operating System. Software Engineering, ISSN: 2229-4007 & ISSN: 2229-4015, Volume 3, Issue 1, pp.-10-13. Copyright: Copyright©2012 Nimodia C. and Deshmukh H.R. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Openmoko Is Dead. Long Live Openphoenux!

Openmoko is dead. Long live OpenPhoenux! Nikolaus Schaller, Lukas Märdian LinuxTag, Berlin, May 26th, 2012 Agenda Part one: some history Part two: a long way home Part three: rising from the ashes Part four: flying higher Part five: use it as daily phone – software Q&A Nikolaus Schaller, Lukas Märdian OpenPhoenux | GTA04 May 26th 2012 LinuxTag 2012 wiki.openmoko.org | www.gta04.org 2 Some history – Past iterations • FIC GTA01 – Neo 1973 – Roughly 3.000 units sold – Production discontinued • Openmoko GTA02 – Neo Freerunner – Roughly 15.000 units sold – Hardware revision v7 – Production discontinued Nikolaus Schaller, Lukas Märdian OpenPhoenux | GTA04 May 26th 2012 LinuxTag 2012 wiki.openmoko.org | www.gta04.org 3 Some history – The End (of part I) • FIC and Openmoko got out • Strong community continues development • Golden Delicious taking the lead – Excellent support for existing devices – Shipping spare parts and add-ons – Tuned GTA02v7++ • Deep sleep fix (aka bug #1024) -> Improved standby time • Bass rework -> Improved sound quality Nikolaus Schaller, Lukas Märdian OpenPhoenux | GTA04 May 26th 2012 LinuxTag 2012 wiki.openmoko.org | www.gta04.org 4 Agenda Part one: some history Part two: a long way home Part three: rising from the ashes Part four: flying higher Part five: use it as daily phone – software Q&A Nikolaus Schaller, Lukas Märdian OpenPhoenux | GTA04 May 26th 2012 LinuxTag 2012 wiki.openmoko.org | www.gta04.org 5 A long way home How do we get to a new open mobile phone? – open kernel for big ${BRAND} – reverse eng. – order from some ${MANUFACTURER} – hope for openness – DIY, “Use the source, Luke!” Nikolaus Schaller, Lukas Märdian OpenPhoenux | GTA04 May 26th 2012 LinuxTag 2012 wiki.openmoko.org | www.gta04.org 6 Using the source: Beagleboard Beagleboard – Full Linux support – Open schematics – Open layout – Expansion connectors – Lots of documentation – Components available Nikolaus Schaller, Lukas Märdian OpenPhoenux | GTA04 May 26th 2012 LinuxTag 2012 wiki.openmoko.org | www.gta04.org 7 In theory it could fit (Aug. -

An Analysis of Power Consumption in a Smartphone

An Analysis of Power Consumption in a Smartphone Josh Hildebrand Introduction l Mobile devices derive the energy required to operate from batteries that are limited by the size of the device. l The ability to manage energy usage requires a good understanding of where and how the energy is being used. l The advancing functionality of modern smartphones is increasing the pressure on battery lifetime, and increases the need for effective energy management. l Goal is to break down a modern smartphone and measure the power consumption of the devices major subsystems, under a range of usage scenarios. l Results from the breakdown of energy consumption will be validated against two additional mobile devices. l Finally, an analysis of the energy consumption will be performed, and an energy model will be created to allow us to model usage patterns. Methodology / Device Under Test l The approach is to take physical power measurements at the component level on a piece of real hardware. l Three elements to the experimental setup, the device under test, a hardware data acquisition (DAQ) system, and a host computer. l Device under test is the Openmoko Neo Freerunner 2.5G smartphone. Experimental Setup l To measure power to each component, supply voltage and current must be measured. l Current is measured by placing sense resistors on the power supply rails of each component. Resistors were selected such that the voltage drop did not exceed 10mV, less than 1% of the supply voltage. l Voltages were measured using a National Instruments PCI-6229 DAQ. Software l The device was running the Freerunner port of Android 1.5, using the Linux v2.6.29 kernel. -

A Survey Onmobile Operating System and Mobile Networks

A SURVEY ONMOBILE OPERATING SYSTEM AND MOBILE NETWORKS Vignesh Kumar K1, Nagarajan R2 (1Departmen of Computer Science, PhD Research Scholar, Sri Ramakrishna College of Arts And Science, India) (2Department of Computer Science, Assistant Professor, Sri Ramakrishna College Of Arts And Science, India) ABSTRACT The use of smartphones is growing at an unprecedented rate and is projected to soon passlaptops as consumers’ mobile platform of choice. The proliferation of these devices hascreated new opportunities for mobile researchers; however, when faced with hundreds ofdevices across nearly a dozen development platforms, selecting the ideal platform is often met with unanswered questions. This paper considers desirable characteristics of mobileplatforms necessary for mobile networks research. Key words:smart phones,platforms, mobile networks,mobileplatforms. I.INTRODUCTION In a mobile network, position of MNs has been changing due todynamic nature. The dynamic movements of MNs are tracked regularlyby MM. To meet the QoS in mobile networks, the various issuesconsidered such as MM, handoff methods, call dropping, call blockingmethods, network throughput, routing overhead and PDR are discussed. In this paper I analyse the five most popular smartphone platforms: Android (Linux), BlackBerry, IPhone, Symbian, and Windows Mobile. Each has its own set of strengths and weaknesses; some platforms trade off security for openness, code portability for stability, and limit APIs for robustness. This analysis focuses on the APIs that platforms expose to applications; however in practice, smartphones are manufactured with different physical functionality. Therefore certain platform APIs may not be available on all smartphones. II.MOBILITY MANAGEMENT IP mobility management protocols proposed by Alnasouri et al (2007), Dell'Uomo and Scarrone (2002) and He and Cheng (2011) are compared in terms of handoff latency and packet loss during HM. -

Digital Vision Network 5000 Series BCM Motherboard BIOS Upgrade

Digital Vision Network 5000 Series BCM™ Motherboard BIOS Upgrade Instructions October, 2011 24-10129-128 Rev. – Copyright 2011 Johnson Controls, Inc. All Rights Reserved (805) 522-5555 www.johnsoncontrols.com No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior permission of Johnson Controls, Inc. Cardkey P2000, BadgeMaster, and Metasys are trademarks of Johnson Controls, Inc. All other company and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. These instructions are supplemental. Some times they are supplemental to other manufacturer’s documentation. Never discard other manufacturer’s documentation. Publications from Johnson Controls, Inc. are not intended to duplicate nor replace other manufacturer’s documentation. Due to continuous development of our products, the information in this document is subject to change without notice. Johnson Controls, Inc. shall not be liable for errors contained herein or for incidental or consequential damages in connection with furnishing or use of this material. Contents of this publication may be preliminary and/or may be changed at any time without any obligation to notify anyone of such revision or change, and shall not be regarded as a warranty. If this document is translated from the original English version by Johnson Controls, Inc., all reasonable endeavors will be used to ensure the accuracy of translation. Johnson Controls, Inc. shall not be liable for any translation errors contained herein or for incidental or consequential damages in connection -

Guide to Enterprise Patch Management Technologies

NIST Special Publication 800-40 Revision 3 Guide to Enterprise Patch Management Technologies Murugiah Souppaya Karen Scarfone C O M P U T E R S E C U R I T Y NIST Special Publication 800-40 Revision 3 Guide to Enterprise Patch Management Technologies Murugiah Souppaya Computer Security Division Information Technology Laboratory Karen Scarfone Scarfone Cybersecurity Clifton, VA July 2013 U.S. Department of Commerce Penny Pritzker, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Patrick D. Gallagher, Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology and Director Authority This publication has been developed by NIST to further its statutory responsibilities under the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA), Public Law (P.L.) 107-347. NIST is responsible for developing information security standards and guidelines, including minimum requirements for Federal information systems, but such standards and guidelines shall not apply to national security systems without the express approval of appropriate Federal officials exercising policy authority over such systems. This guideline is consistent with the requirements of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-130, Section 8b(3), Securing Agency Information Systems, as analyzed in Circular A- 130, Appendix IV: Analysis of Key Sections. Supplemental information is provided in Circular A-130, Appendix III, Security of Federal Automated Information Resources. Nothing in this publication should be taken to contradict the standards and guidelines made mandatory and binding on Federal agencies by the Secretary of Commerce under statutory authority. Nor should these guidelines be interpreted as altering or superseding the existing authorities of the Secretary of Commerce, Director of the OMB, or any other Federal official. -

Android 10 OS Update Instruction for Family of Products on SDM660

Android 10 OS Update Instruction for Family of Products on SDM660 1 Contents 1. A/B (Seamless) OS Update implementation on SDM660 devices ................................................................................................... 2 2. How AB system is different to Non-AB system ............................................................................................................................... 3 3. Android AB Mode for OS Update .................................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Recovery Mode for OS Update ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 5. Reset Packages and special recovery packages ................................................................................................................................ 4 6. OS Upgrade and Downgrade ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 7. OS Upgrade and Downgrade via EMMs .......................................................................................................................................... 6 8. AB Streaming Update ....................................................................................................................................................................... 7 9. User Notification for Full OTA package -

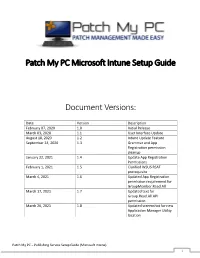

Patch My PC Microsoft Intune Setup Guide Document Versions

Patch My PC Microsoft Intune Setup Guide Document Versions: Date Version Description February 07, 2020 1.0 Initial Release March 03, 2020 1.1 User Interface Update August 18, 2020 1.2 Intune Update Feature September 24, 2020 1.3 Grammar and App Registration permission cleanup January 22, 2021 1.4 Update App Registration Permissions February 1, 2021 1.5 Clarified WSUS RSAT prerequisite March 4, 2021 1.6 Updated App Registration permission requirement for GroupMember.Read.All March 17, 2021 1.7 Updated text for Group.Read.All API permission March 26, 2021 1.8 Updated screenshot for new Application Manager Utility location Patch My PC – Publishing Service Setup Guide (Microsoft Intune) 1 System Requirements: • Microsoft .NET Framework 4.5 • Supported Operating Systems o Windows Server 2008 o Windows Server 2012 o Windows Server 2016 o Windows Server 2019 o Windows 10 (x64) – Microsoft Intune only Prerequisites: • WSUS Remote Server Administration Tools (RSAT) to be installed Download the latest MSI installer of the publishing service using the following URL: https://patchmypc.com/publishing- service-download Start the installation by double- clicking the downloaded MSI. Note: Depending on user account control settings, you may need to run an elevated command prompt and launch the MSI from the command prompt. Click Next in the Welcome Wizard Click Next in the Installation Folder Dialog Optionally, you can change the installation folder by clicking Browse… Click Install on the Ready to Install dialog. Note: if user-account control is enabled, you will receive a prompt “Do you want to allow this app to make changes to your device?” Click Yes on this prompt to allow installation Patch My PC – Publishing Service Setup Guide (Microsoft Intune) 2 If you are configuring the product for Intune Win32 application publishing only, you can check Enable Microsoft Intune standalone mode When this option is enabled, prerequisite checks related to WSUS and Configuration Manager are skipped. -

Patch Management for Redhat Enterprise Linux

Patch Management for RedHat Enterprise Linux Supported Versions BigFix provides coverage for RedHat updates on the following platforms: • RedHat Enterprise Linux 5 • RedHat Enterprise Linux 4 • RedHat Enterprise Linux 3 BigFix covers the following RedHat updates on these platforms: • RedHat Security Advisories • RedHat Bug Fix Advisories • RedHat Enhancement Advisories Patching using Fixlet Messages To deploy patches from the BigFix Console: 1. On the Fixlet messages tab, sort by Site. Choose the Site Patches for RedHat Enterprise Linux. 2. Double-click on the Fixlet message you want to deploy. (In this example, the Fixlet message is RHSA-2007:0992 - Libpng Security Update - Red Hat Enterprise 3.0.) The Fixlet window opens. For more information about setting options using the tabs in the Fixlet window, consult the Console Operators Guide. 3. Select the appropriate Action link. © 2007 by BigFix, Inc. BigFix Patch Management for RedHat Enterprise Linux Page 2 A Take Action window opens. For more information about setting options using the tabs in the Take Action dialog box, consult the Console Operators Guide. 4. Click OK, and enter your Private Key Password when asked. Using the Download Cacher The Download Cacher is designed to automatically download and cache RedHat RPM packages to facilitate deployment of RedHat Enterprise Linux Fixlet messages. Running the Download Cacher Task BigFix provides a Task for running the Download Cacher Tool for RedHat Enterprise Linux. 1. From the Tasks tab, choose Run Download Cacher Tool – Red Hat Enterprise. The Task window opens. © 2007 by BigFix, Inc. BigFix Patch Management for RedHat Enterprise Linux Page 3 2. Select the appropriate Actiont link. -

Mind the Gap: Dissecting the Android Patch Gap | Ben Schlabs

Mind the Gap – Dissecting the Android patch gap Ben Schlabs <[email protected]> SRLabs Template v12 Corporate Design 2016 Allow us to take you on two intertwined journeys This talk in a nutshell § Wanted to understand how fully-maintained Android phones can be exploited Research § Found surprisingly large patch gaps for many Android vendors journey – some of these are already being closed § Also found Android exploitation to be unexpectedly difficult § Wanted to check thousands of firmwares for the presence of Das Logo Horizontal hundreds of patches — Pos / Neg Engineering § Developed and scaled a rather unique analysis method journey § Created an app for your own analysis 2 3 Android patching is a known-hard problem Patching challenges Patch ecosystems § Computer OS vendors regularly issue patches OS vendor § Users “only” have to confirm the installation of § Microsoft OS patches Patching is hard these patches § Apple Endpoints & severs to start with § Still, enterprises consider regular patching § Linux distro among the most effortful security tasks § “The moBile ecosystem’s diversity […] OS Chipset Phone Android contriButes to security update complexity and vendor vendor vendor phones inconsistency.” – FTC report, March 2018 [1] The nature of Telco § Das Logo HorizontalAndroid makes Patches are handed down a long chain of — Pos / Negpatching so typically four parties Before reaching the user much more § Only some devices get patched (2016: 17% [2]). difficult We focus our research on these “fully patched” phones Our research question –