Greater Roadrunner Geococcyx Californianus an Emblem of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roadrunner Fact Sheet

Roadrunner Fact Sheet Common Name: Roadrunner Scientific Name: Geococcyx Californianus & Geococcyx Velox Wild Status: Not Threatened Habitat: Arid dessert and shrub Country: United States, Mexico, and Central America Shelter: These birds nest 1-3 meters off the ground in low trees, shrubs, or cactus Life Span: 8 years Size: 2 feet in length; 8-15 ounces Details The genus Geococcyx consists of two species of bird: the greater roadrunner and the lesser roadrunner. They live in the arid climates of Southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America. Though these birds can fly, they spend most of their time running from shrub to shrub. Roadrunners spend the entirety of their day hunting prey and dodging predators. It's a tough life out there in the wild! These birds eat insects, small reptiles and mammals, arachnids, snails, other birds, eggs, fruit, and seeds. One thing that these birds do not have to worry about is drinking water. They intake enough moisture through their diet and are able to secrete any excess salt build-up through glands in their eyes. This adaptation is common in sea birds as their main source of hydration is the ocean. The fact that roadrunners have adapted this trait as well goes to show how well they are suited for their environment. A roadrunner will mate for life and will travel in pairs, guarding their territory from other roadrunners. When taking care of the nest, both male and female take turns incubating eggs and caring for their young. The young will leave the nest after a couple weeks and will then learn foraging techniques for a few days until they are left to fend for themselves. -

Spring 2009 RURAL LIVING in ARIZONA Volume 3, Number 2

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES Backyards& Beyond Spring 2009 RURAL LIVING IN ARIZONA Volume 3, Number 2 Spring 2009 1 Common Name: Globemallow Scientific Name: Sphaeralcea spp. Globemallow is a common native wildflower found throughout most of Arizona. There are 16 species (and several varieties) occurring in the state, the majority of which are perennials. They are found between 1,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation and grow on a variety of soil types. Depending on the species, globemallows are either herbaceous or slightly woody at the base of the plant and grow between 2-3 feet in height (annual species may only grow to 6 inches). The leaves are three-lobed, and while the shape varies by species, they are similar enough to help identify the plant as a globemallow. The leaves have star-shaped hairs that give the foliage a gray-green color. Flower color Plant Susan Pater varies from apricot (the most common) to red, pink, lavender, pale yellow and white. Many of the globemallows flower in spring and again in summer. Another common name for globemallow is sore-eye poppy (mal de ojos in Spanish), from claims that the plant irritates the eyes. In southern California globemallows are known as plantas muy malas, translated to mean very bad plants. Ironically, the Pima Indian name for globemallow means a cure for sore eyes. The Hopi Indians used the plant for healing certain ailments and the stems as a type of chewing gum, and call the plant kopona. -

Arizona's Raptor Experience, LLC June 2019 ~Newsletter~

Arizona’s Raptor Experience, LLC June 2019 ~Newsletter~ Greetings from Chino Valley! We hope you are well and staying cool in the summer heat. It’s baby bird season and we’ve had lots of excitement around the house. A pair of Say’s Phoebes nested under the eaves of our porch giving us a front row seat for watching them bring an endless number of insects to their two young all day long, every day! House Finches are nesting in the rafters of the bird mews and the Gambel’s Quail have started showing up on the hill with the first hatchlings of the season. This morning a day-old quail chick was separated from its mother and ended up on the back porch. All we could do was catch the little guy and put it up on the hill with the hopes it would find its mother. This experience reminded me of the many perils faced by baby birds, even before they hatch. This newsletter will focus on one of those perils…the threat of carnivorous birds. We hope you enjoy it! Young American Kestrel recently banded then returned to a nest box we put up as a part of the American Kestrel Partnership. Birds of Prey…or are they? Not all carnivorous birds are built the same. To be classified as a bird of prey, or raptor, a bird must have powerful feet with talons for holding and killing prey and a hooked beak for killing prey and tearing/eating flesh. All birds of prey are considered carnivorous, or meat eaters, and they can be placed into categories based on the type of meat: Piscivores: fish eating (ex: Bald Eagles, Osprey) Insectivores: insect eating (ex: Swainson’s Hawks, American Kestrels) Greater Roadrunner Avivores: bird eating (ex: Cooper’s P.Schnell photo Hawk, Peregrine Falcon) Scavengers: carrion eating (old world vultures – still classified as raptors) However, many birds that are meat-eaters are not raptors. -

Birds of the Ironwood Forest Sharp-Shinned Hawk

Birds of the Ironwood Forest Sharp-shinned Hawk • Long tailed hawks with rounded wings • Females are substan5ally larger than males • Generally found in dense forest areas • During migraon they are usually seen in open habitats along ridgelines. • Known to have dis5nc5ve flap and gluide flight paerns White-throated Swi • One of the fastest birds in North America • Commonly found in canyons, foothills, and mountains in the SW • Highly social birds, known to roost in groups of hundreds • Nest in large cavi5es in cliffs and large rocks Rufous-winged Sparrow • Only found in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona and Mexico • It depends on the summer monsoons to begin nes5ng • They typically nest in shrubs • They stay bonded for life and remain in the same area year-round Back-throated Sparrow • Commonly found in open, shrubby deserts • The males hold a large territory when nes5ng first begins • Males are known to sin from high perches while the females build the nests • During the winter the birds primarily eat seeds while in the summer switching mostly to insects Verdin • Known to be very vocal and conspicuous • A small yellow and grey songbird • The Verdin builds two separate nests, one for breeding and another for roos5ng • They consistently build nests year round • The roos5ng nests are much thicker intended for insulaon during the winter • Commonly found in thorny shrub Great Horned Owl • Most commonly found in forests but can also be spo@ed in a variety of habitats • Fierce predators that will eat large mammals to small rodents and amphibians • Their -

Gila Monster Saguaro Cactus Roadrunner Coyote Elf Owl Mule

Gila Monster Saguaro Cactus Roadrunner Coyote Elf Owl Mule Deer Javelina Desert Tortoise Ocotillo Tarantula Bobcat Cholla Cactus Desert Toad Jackrabbit Prickly Pear Cactus Rattlesnake http:thefilesofmrse.com Bobcat Rattlesnake Desert Toad Tarantula Jackrabbit Cholla Cactus Ocotillo Gila Monster Prickly Pear Cactus Elf Owl Saguaro Cactus Mule Deer Coyote Javelina Desert Tortoise Roadrunner http:thefilesofmrse.com Saguaro Cactus Coyote Jackrabbit Javelina Desert Tortoise Ocotillo Elf Owl Rattlesnake Bobcat Cholla Cactus Prickly Pear Cactus Desert Toad Mule Deer Roadrunner Gila Monster Tarantula http:thefilesofmrse.com Desert Toad Desert Tortoise Saguaro Cactus Bobcat Jackrabbit Mule Deer Cholla Cactus Gila Monster Prickly Pear Cactus Elf Owl Tarantula Javelina Coyote Rattlesnake Roadrunner Ocotillo http:thefilesofmrse.com Javelina Gila Monster Roadrunner Ocotillo Rattlesnake Bobcat Prickly Pear Cactus Elf Owl Saguaro Cactus Tarantula Coyote Jackrabbit Desert Toad Desert Tortoise Mule Deer Cholla Cactus http:thefilesofmrse.com Jackrabbit Prickly Pear Cactus Rattlesnake Desert Tortoise Desert Toad Coyote Ocotillo Gila Monster Cholla Cactus Mule Deer Bobcat Javelina Roadrunner Tarantula Saguaro Cactus Elf Owl http:thefilesofmrse.com Coyote Mule Deer Desert Toad Saguaro Cactus Desert Tortoise Prickly Pear Cactus Gila Monster Roadrunner Javelina Elf Owl Tarantula Ocotillo Rattlesnake Jackrabbit Cholla Cactus Bobcat http:thefilesofmrse.com Tarantula Elf Owl Javelina Prickly Pear Cactus Desert Tortoise Saguaro Cactus Gila Monster Rattlesnake Bobcat -

Memorial Text for SJM042

1 A JOINT MEMORIAL 2 DECLARING MARCH 16, 2009 THE "DAY OF THE ROADRUNNER" AT THE 3 LEGISLATURE TO RECOGNIZE THE SIXTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE 4 ADOPTION OF THE ROADRUNNER AS NEW MEXICO'S STATE BIRD AND TO 5 HONOR AND CELEBRATE THE ROADRUNNER. 6 7 WHEREAS, the roadrunner, or chaparral, is New Mexico's 8 state bird; and 9 WHEREAS, the roadrunner was adopted as the state bird on 10 March 16, 1949; and 11 WHEREAS, the roadrunner darts, dashes and roams 12 throughout the state with the exception of the Four Corners 13 area; and 14 WHEREAS, the image of the roadrunner with its 15 distinctive head crest, thick beak, long legs and exaggerated 16 tail has become an icon for all New Mexicans; and 17 WHEREAS, the colors of the roadrunner are said to 18 reflect the colors of the desert; and 19 WHEREAS, the land-loving bird can run at speeds of up to 20 fifteen miles per hour and often sprints rather than flying; 21 and 22 WHEREAS, the roadrunner is an opportunistic omnivore, 23 living on insects; small reptiles, including lizards and 24 snakes; rodents and small mammals; tarantulas; scorpions; 25 centipedes; spiders; small birds, eggs and nestlings; and SJM 42 Page 1 1 fruits and seeds, such as prickly pear cactus and sumac; and 2 WHEREAS, the roadrunner is the only known predator of 3 the tarantula hawk wasp; and 4 WHEREAS, the roadrunner, which may have a wingspan of up 5 to three feet wide, lowers its body temperature during cold 6 desert nights, going into a slight torpor to conserve energy; 7 and 8 WHEREAS, the roadrunner warms itself during the -

Critter Class Roadrunners

Critter Class Greater Roadrunner Roadrunners October 5, 2011 Comment HI MVK! How about Roadrunners tonight. MVK: hmm roadrunners - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BoprwQYS_ic Comment: They sometimes nest in Cactus! Comment: Hi MVK! Glad you are here! Roadrunner sounds like fun! Bet EGS would like that. Comment: Road runner birds never knew they didn’t fly much Comment: Roadrunners, now that's actually some wildlife I've seen in Phoenix. Comment: The roadrunner is the state bird of NM. They run very very fast especially across a highway. Comment: Willy coyote! One of my favorite cartoons! Telling my age. MVK: EGS wherever you are - the roadrunner is a zygodactyl MVK: They are a member of the cuckoo family! Comment: Roadrunners, eh? Bet someone finds a youtube video of them soaring in the skies just like those penguins... :) MVK: The roadrunner is about 56 centimeters (22 in) long and weighs about 300 grams (10.5 oz), and is the largest North American cuckoo. The adult has a bushy crest and long thick dark bill. It has a long dark tail, a dark head and back, and is blue on the front of the neck and Critter Class – Roadrunners 1 10/5/2011 on the belly. Roadrunners have four toes on each zygodactyl foot; two face forward, and two face backward. Per Wikipedia MVK: The breeding habitat is desert and shrubby country in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. It can be seen in the US states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Oklahoma, and rarely in Kansas, Louisiana, Arkansas and Missouri,[3] as well as the Mexican states of Baja California, Baja California Sur, Sonora, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, Durango, Jalisco, Coahuila, Zacatecas, Aguas Calientes, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Querétaro, México, Puebla, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and San Luis Potosí.[4] Per Qikipedia Comment: Are the Roadrunners found on any other continent? MVK: Greater Roadrunner on the run The Greater Roadrunner nests on a platform of sticks low in a cactus or a bush and lays 3–6 eggs, which hatch in 20 days. -

Backyards Birds of the Brazos Valley

BACKYARDS BIRDS OF THE BRAZOS VALLEY Western Diamondback Rattlesnake • Species in the world- about 10,000 • Species in the US- about 820 • Species in Texas- about 630 • Species in BV- about 300 • How many in your backyard? What birds need • Food – seeds, suet, sugar water (bush/tree nearby), fruit, ”protein” such as mealworms • Water – birdbath (shallow!), creek/running water, drip, mister, pond • (use mosquito control!) • Shelter – Box (2 kinds-nest and roost), roosting bush/tree, protection after bath Northern Mockingbird Loggerhead Shrike Loggerhead Shrike Scissor-tailed Flycatcher Eastern Kingbird Western Kingbird Eastern Phoebe Northern Cardinal Northern Cardinal Red-capped Cardinal Eastern Bluebird male Eastern Bluebird female Carolina Wren American Goldfinch American Goldfinch Ruby-throated Hummingbird Rufous Hummingbird Anna’s Hummingbird Buff-bellied Hummingbird Mourning Dovee Inca Dove White-winged Dove Eurasian collared Dove Rock Pigeon / Rock Dove American Crow Chimney Swift Chimney swift tower Chimney swift nest-eggs Purple Martin Purple Bartin box + gourds Ooooooops Barn Swallow Barn Swallow nest Barn Swallow nest Barn Swallow nest base Red-bellied Woodpecker Red-bellied Woodpecker Red-headed Woodpecker Downy Woodpecker Pileated Woodpecker Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Black-and-white Warbler Yellow Warbler Wilson’s Warbler Cerulean Warbler Yellow-rumped Warbler Chestnut-sided Warbler Black-throated Green Warbler Blackburnian Warbler Prothonotary Warbler Painted Bunting Indigo Bunting Great Egret Great-blue Heron Green Heron Killdeer -

Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation for Leconte's

Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation for LeConte’s (Toxostoma lecontei) and Bendire’s (Toxostoma bendirei) Thrasher Prepared by: The Desert Thrasher Working Group Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation Contents Objective 3 Field Gear and Materials Checklist: 4 Conducting the Survey 6 Thrasher Survey Form 8 Target Species Sighting Form 10 Habitat Evaluation Form 12 Data entry 16 Analysis of Area Search Data: Site-Level Models 17 Appendix 1. Species Descriptions 19 LeConte’s Thrasher 19 Bendire’s Thrasher 20 Appendix 2. Training Materials 22 Appendix 3. Bird and Plant Abbreviations and Codes 25 Appendix 4. Sample Survey Form 33 Appendix 5. Sample Sighting Form 34 Appendix 6. Group Code Examples 35 Appendix 7. Sample Habitat Evaluation Form 37 Appendix 8. Invasive Plant Identification Resources. 38 Recommended Citation: DTWG, the Desert Thrasher Working Group. 2018. Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation for LeConte’s and Bendire’sThrashers. The Protocol Subteam with the Desert Thrasher Working Group included: Dawn M. Fletcher, Lauren B. Harter, Christina L. Kondrat-Smith, Christofolos L. McCreedy and Collin A. Woolley. Cover photo art by: Christina Kondrat-Smith 2 Survey Protocol and Habitat Evaluation Objective The objectives of these surveys are to estimate distribution, determine population trends over time, and to identify habitat preferences for Bendire’s and LeConte’s Thrashers. Recommended Survey Times: Consider local elevation and latitude when designing a survey schedule, as researchers will need to balance surveying early (which helps to minimize confusion of adults with juveniles, and which may maximize exposure to peak singing season) with surveying late (which can minimize the possibility of completely missing late-arriving, migratory Bendire’s Thrashers). -

New Information on the Late Pleistocene Birds from San Josecito Cave, Nuevo Leon, Mexico ’

A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY Volume 96 Number 3 The Condor96571-589 Q The Cooper Omithologkzd %cietY 1994 NEW INFORMATION ON THE LATE PLEISTOCENE BIRDS FROM SAN JOSECITO CAVE, NUEVO LEON, MEXICO ’ DAVID W. STEADMAN New York State Museum, The State Education Department, Albany, NY 12230 JOAQUIN ARROYO-CARRALES Museum of Texas Tech University,Lubbock, TX 79409 and Laboratorio de Paleozoologia,Subdireccion de ServiciosAcademicos, Instituto National de Antropologiae Historia, Mexico EILEEN JOHNSON Museum of Texas Tech University,Lubbock, TX 79409 A. FARIOLA GUZMAN Laboratorio de Paleozoologta,Subdireccibn de ServiciosAcademicos, Instituto National de Antropologiiae Historia, Mexico Abstract. We report 90 bird bones representing 18 speciesfrom recent excavations at San Josecito Gave, Nuevo Le6n, Mexico. The new material increasesthe avifauna of this rich late Pleistocenelocality from 52 to 62 species.Eight of the 10 newly recorded taxa are extant; each is either of temperate rather than tropical affinities (such as the American Woodcock Scolopax minor and Pinyon Jay Gymnorhinuscyanocephalus) or is very wide- spreadin its modem distribution. The two extinct taxa are a stork (Ciconia sp. or Mycteria sp.) and Geococcyxcalifornianus conklingi, a large temporal subspeciesof the Greater Road- runner. In this region of the Sierra Madre Oriental (about lat. 24”N, long. lOO”W, elev. 2,000-2,600 m). the late Pleistocene avifauna was a mixture of speciesthat to&y prefer coniferous or pine-oak forests/woodlands,grasslands/savannas, and wetlands. As with var- ious late Pleistoceneplant and mammal communities of the United Statesand Mexico, no clear modem analog exists for the late Pleistoceneavifauna of San JosecitoCave. Key words: Late Pleistoceneavzfaunas; Mexico; historicalbiogeography; extinct species; temperate/tropicaltransition. -

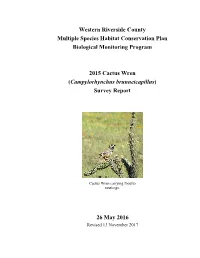

Cactus Wren Survey Report 2015

Western Riverside County Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan Biological Monitoring Program 2015 Cactus Wren (Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus) Survey Report Cactus Wren carrying food to nestlings. 26 May 2016 Revised 13 November 2017 2015 Cactus Wren Report TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................... 1 METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 2 SURVEY DESIGN ........................................................................................................................... 3 FIELD METHODS ........................................................................................................................... 3 DATA ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................................... 4 RESULTS .............................................................................................................................. 4 CACTUS WREN DETECTIONS ........................................................................................................ 4 DETECTION PROBABILITY ANALYSIS ........................................................................................... 5 DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................................ -

Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx Californianus) Home Range and Habitat Selection in West Texas

Western North American Naturalist Volume 74 Number 2 Article 5 8-27-2014 Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus) home range and habitat selection in west Texas Andrea E. Montalvo Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, [email protected] Dean Ransom Jr. Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, [email protected] Roel R. Lopez Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Part of the Anatomy Commons, Botany Commons, Physiology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Montalvo, Andrea E.; Ransom, Dean Jr.; and Lopez, Roel R. (2014) "Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus) home range and habitat selection in west Texas," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 74 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol74/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 74(2), © 2014, pp. 201–207 GREATER ROADRUNNER (GEOCOCCYX CALIFORNIANUS) HOME RANGE AND HABITAT SELECTION IN WEST TEXAS Andrea E. Montalvo1,2, Dean Ransom Jr.1, and Roel R. Lopez1 ABSTRACT.—We studied Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus) habitat use during spring and summer 2011 on the Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch in the Red Rolling Plains of west Texas. We captured 9 roadrunners (1 male, 8 females) and fitted each with a 10-g backpack-style radio-transmitter.