449 the Construction of Chinese National Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Message from the Representative Taiwan

MESSAGE FROM THE REPRESENTATIVE The approach of Christmas and the New Year always provides much time for reflection, and I am pleased to say that we have made steady progress in the bilateral ties between the UK and Taiwan since my arrival in London in late August. This progress has encompassed a wide range of fields, from education to renewable energy and gives us much to build upon as we proceed into 2017. December characteristically sees a great amount of activity throughout our diplomatic missions around the world. Our Christmas receptions for our allies in parliament and the diplomatic corps were a great success, functioning as an excellent opportunity to bring together Taiwan’s friends and to express our gratitude for the hard work and support which they have shown consistently throughout the year. We have recently welcomed Taiwan’s Minister Without Portfolio to the UK, where she delivered two excellent speeches here in London, showcasing to a global audience Taiwan’s efforts to promote open government through digital tools. I was also delighted to make a trip to the Kent constituency of South Thanet, where I had the pleasure of advancing UK-Taiwan ties in renewable energy with Mr Craig Mackinlay, the constituency’s MP. The year 2016 has in many respects been a remarkable one, having been characterised by much change. For Taiwan, this year constituted the second peaceful transfer of governmental powers in the country’s history and was another testament to the success of our democracy. While significant changes may bring challenges, they also often bring significant opportunities and I am confident we will be able to utilise these throughout the months and years ahead. -

Interdisciplinary, and Some Resources for History, Philosophy, Religion, and Literature Are Also Included in the Guide. Images A

Bard Graduate Center Research Guide: Ancient and Medieval China (to c. 1000 C.E.) This guide lists resources for researching the arts and material culture of ancient and medieval imperial China, to c. 1000 C.E. This time period begins with the neolithic and bronze ages (c. 4000 - 200 B.C.E.) and continues through the end of the Five Dynasties period (960 C.E.), including the Xia, Shang, Zhou, Han, and T'ang dynasties. Although art history and material archaeology resources are emphasized, research on this topic is very interdisciplinary, and some resources for history, philosophy, religion, and literature are also included in the guide. This guide was compiled by Karyn Hinkle at the Bard Graduate Center Library. Images above, left to right: a gold cup from the Warring States period, jade deer from the Zhou dynasty, a bronze wine vessel from the Shang dynasty, all described in Patricia Buckley Ebrey's Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization. Reference sources for ancient and medieval China Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, and Kwang-Ching Liu. The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. DS 706 .E37 1996 Loewe, Michael and Edward L. Shaughnessy. The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. DS 741.5 .C35 1999; also available online through Bard College Nadeau, Randall Laird, ed. The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Chinese Religions. Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Religion. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. Available online through Bard College Gold Monster Shaanxi Museum The Han Dynasty Length:11 cm Height:11.5 cm Unearthed in 1957 from Gaotucun,Shenmu County,Shaanxi Province Important books on ancient and medieval China, and good general introductions to Chinese history and art Boyd, Andrew. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Culturalism Through Public Art Practices

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2011 Assessing (Multi)culturalism through Public Art Practices Anru Lee CUNY John Jay College of Criminal Justice Perng-juh Peter Shyong How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/49 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 How to Cite: Lee, Anru, and Perng-juh Peter Shyong. 2011. “Assessing (Multi)culturalism through Public Art Practices.” In Tak-Wing Ngo and Hong-zen Wang (eds.) Politics of Difference in Taiwan. Pp. 181-207. London and New York: Routledge. 2 Assessing (Multi)culturalism through Public Art Practices Anru Lee and Perng-juh Peter Shyong This chapter investigates the issue of multiculturalism through public art practices in Taiwan. Specifically, we focus on the public art project of the Mass 14Rapid Transit System in Kaohsiung (hereafter, Kaohsiung MRT), and examine how the discourse of multiculturalism intertwines with the discourse of public art that informs the practice of the latter. Multiculturalism in this case is considered as an ideological embodiment of the politics of difference, wherein our main concern is placed on the ways in which different constituencies in Kaohsiung respond to the political-economic ordering of Kaohsiung in post-Second World War Taiwan and to the challenges Kaohsiung City faces in the recent events engendering global economic change. We see the Kaohsiung MRT public art project as a field of contentions and its public artwork as a ‘device of imagination’ and ‘technique of representation’ (see Ngo and Wang in this volume). -

This Is V1.1 of the 54Th Worldfest-Houston Remi Winners List

This is V1.1 of the 54th WorldFest-Houston Remi Winners List. We have been delayed by Covid19, and we will be revising the Winners List over the next 10 days! WorldFest-Houston is the only film festival in the world that gives your entry a score, a grade! Therefore there can be several Remi Winners in each category. This year, despite Covid19, we have more than 4,500 Category Entries,& only about 10-15% won a Remi Award! 79 Countries participated! Our sincere Congratulations to our Remi Award Winners for the 54th Annual WorldFest-Houston International Film Festival! FirstName Last Name Project Title REMI AWARD Category Directors Producers Category Country of Or Remi Award Recipient (*The name of the company or individual to appear on your Remi Award if nominated.) Ross Wilson Spin State GOLD REMI Feature Ross A Wilson Ross A Wilson, Donna Entick 22 UK Ross A Wilson Farah Abdo A Lonely Afternoon SILVER REMI Short Kyle Credo Farah Abdo 312 Canada Kyle Credo Elika Abdollahi Pass PLATINUM REMI Short, Student Elika Abdollahi Elika Abdollahi 602 IRAN Elika Abdollahi Kevin Abrams I Got a Monster PLATINUM REMI Documentary Kevin Abrams Jamie Denenberg, Auriell Spi 233 USA Kevin Abrams Olga Akatyeva Fib the truth BRONZE REMI Feature OLGA AKATYEVA GEORGIY SHABANOV OLG 15 Russian Feder Olga Akatyeva JIM ALLODI Bella Wild PLATINUM REMI Short JIM ALLODI Penny McDonald , Jim Allodi 311 canada Jim Allodi JIM ALLODI Delivery SILVER REMI Shorts 311 JIM ALLODI Penny McDonald 311 CANADA JIM ALLODI, PENNY McDONALD, CARL KNUTSON Daniel Altschul Buffalo Bayou -

Download File

On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Xiaohan Du All Rights Reserved Abstract On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du This dissertation is the first monographic study of the monk-calligrapher Yishan Yining (1247- 1317), who was sent to Japan in 1299 as an imperial envoy by Emperor Chengzong (Temur, 1265-1307. r. 1294-1307), and achieved unprecedented success there. Through careful visual analysis of his extant oeuvre, this study situates Yishan’s calligraphy synchronically in the context of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy at the turn of the 14th century and diachronically in the history of the relationship between calligraphy and Buddhism. This study also examines Yishan’s prolific inscriptional practice, in particular the relationship between text and image, and its connection to the rise of ink monochrome landscape painting genre in 14th century Japan. This study fills a gap in the history of Chinese calligraphy, from which monk- calligraphers and their practices have received little attention. It also contributes to existing Japanese scholarship on bokuseki by relating Zen calligraphy to religious and political currents in Kamakura Japan. Furthermore, this study questions the validity of the “China influences Japan” model in the history of calligraphy and proposes a more fluid and nuanced model of synthesis between the wa and the kan (Japanese and Chinese) in examining cultural practices in East Asian culture. -

A Study on Consumers' Preferences for the Palace Museum's Cultural

sustainability Article A Study on Consumers’ Preferences for the Palace Museum’s Cultural and Creative Products from the Perspective of Cultural Sustainability Jui-Che Tu 1, Li-Xia Liu 1,2 and Yang Cui 3,* 1 Graduate School of Design, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Yunlin 64002, Taiwan; [email protected] (J.-C.T.); [email protected] (L.-X.L.) 2 College of Arts, Beijing Union University, Beijing 100101, China 3 School of Art and Communication, Beijing Technology and Business University, Beijing 100048, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 24 April 2019; Accepted: 14 June 2019; Published: 26 June 2019 Abstract: In recent years, the development and design of the cultural and creative products of the Palace Museum in Beijing have become a hot topic in the product design field. Many critics have pointed out that cultural and creative products have failed to faithfully convey the implied meanings of the cultural stories of the Palace Museum. To effectively narrow the cognitive gap between designers and consumers, designers must urgently clarify the relationship between different design attributes and consumer preferences. The questionnaires were used to obtain data from 297 subjects. Through SPSS statistical software, the results were analyzed by descriptive statistics, explore factor analysis (EFA), independent sample t-test, and ANOVA to explore consumers’ attitudes and preferences on the Palace Museum’s cultural and creative products. The results showed that consumers attach great importance to factors such as “cultural connotation” and “unique creativity” when choosing the Palace Museum’s cultural and creative products. The consumer in different genders had significant differences in the design factors of the Palace Museum’s cultural and creative products. -

National Palace Museum Collections Online the National Palace Museum Preserves the Imperial Collections and Palatial Treasures from the Various Chinese Dynasties

National Palace Museum Collections Online The National Palace Museum preserves the imperial collections and palatial treasures from the various Chinese dynasties. Featuring the essence of antiquities, painting, and calligraphy spanning 8,000 years of the Chinese culture, the Museum becomes a treasury and bastion of Chinese art and culture famous the world over. The National Palace Museum Collections Online accumulates a special selection of antiquities, paintings and calligraphies noted for their historic significance, importance, rarity, artistry, and popularity. Through the database, the users may enjoy the masterpieces via the web, experiencing the spiritual contact and art achievements of the Chinese culture. ─1─ SEARch Chinese masterpieces just in front your eyes 3 1 2 The National Palace Museum Collections Online (NPMCO) provides two search modes: Keyword Search and Advanced Search. A Keyword Search will search all data fields for every image in NPMCO. You can also search for multiple words or for exact phrases if you enclose search terms in quotation marks. Enter your keyword in the search box and click Search (1), the NPMCO will return results that include all your search terms in the search result page. The Advanced Search (2) helps you limit your search by field. You can also use Boolean Operators AND, OR & NOT to combine your search terms. You can click the “search (查詢檢索)” button on the navigation bar (3) to return to the search function page when you are in another page. ─2─ SEARch Result page Chinese masterpieces just in front your eyes 3 1 2 (1) Click the caption to view the full data record of that image. -

Nationalist China in the Postcolonial Philippines: Diasporic Anticommunism, Shared Sovereignty, and Ideological Chineseness, 1945-1970S

Nationalist China in the Postcolonial Philippines: Diasporic Anticommunism, Shared Sovereignty, and Ideological Chineseness, 1945-1970s Chien Wen Kung Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Chien Wen Kung All rights reserved ABSTRACT Nationalist China in the Postcolonial Philippines: Diasporic Anticommunism, Shared Sovereignty, and Ideological Chineseness, 1945-1970s Chien Wen Kung This dissertation explains how the Republic of China (ROC), overseas Chinese (huaqiao), and the Philippines, sometimes but not always working with each other, produced and opposed the threat of Chinese communism from the end of World War II to the mid-1970s. It is not a history of US- led anticommunist efforts with respect to the Chinese diaspora, but rather an intra-Asian social and cultural history of anticommunism and nation-building that liberates two close US allies from US- centric historiographies and juxtaposes them with each other and the huaqiao community that they claimed. Three principal arguments flow from this focus on intra-Asian anticommunism. First, I challenge narrowly territorialized understandings of Chinese nationalism by arguing that Taiwan engaged in diasporic nation-building in the Philippines. Whether by helping the Philippine military identify Chinese communists or by mobilizing Philippine huaqiao in support of Taiwan, the ROC carved out a semi-sovereign sphere of influence for itself within a foreign country. It did so through institutions such as schools, the Kuomintang (KMT), and the Philippine-Chinese Anti-Communist League, which functioned transnationally and locally to embed the ROC into Chinese society and connect huaqiao to Taiwan. -

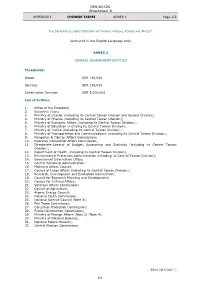

GPA/W/326 Attachment K K1

GPA/W/326 Attachment K APPENDIX I CHINESE TAIPEI ANNEX 1 Page 1/2 THE SEPARATE CUSTOMS TERRITORY OF TAIWAN, PENGHU, KINMEN AND MATSU* (Authentic in the English Language only) ANNEX 1 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ENTITIES Thresholds: Goods SDR 130,000 Services SDR 130,000 Construction Services SDR 5,000,000 List of Entities: 1. Office of the President; 2. Executive Yuan; 3. Ministry of Interior (including its Central Taiwan Division and Second Division); 4. Ministry of Finance (including its Central Taiwan Division); 5. Ministry of Economic Affairs (including its Central Taiwan Division); 6. Ministry of Education (including its Central Taiwan Division); 7. Ministry of Justice (including its Central Taiwan Division); 8. Ministry of Transportation and Communications (including its Central Taiwan Division); 9. Mongolian & Tibetan Affairs Commission; 10. Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission; 11. Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (including its Central Taiwan Division); 12. Department of Health (including its Central Taiwan Division); 13. Environmental Protection Administration (including its Central Taiwan Division); 14. Government Information Office; 15. Central Personnel Administration; 16. Mainland Affairs Council; 17. Council of Labor Affairs (including its Central Taiwan Division); 18. Research, Development and Evaluation Commission; 19. Council for Economic Planning and Development; 20. Council for Cultural Affairs; 21. Veterans Affairs Commission; 22. Council of Agriculture; 23. Atomic Energy Council; 24. National Youth Commission; 25. National Science Council (Note 3); 26. Fair Trade Commission; 27. Consumer Protection Commission; 28. Public Construction Commission; 29. Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Note 2) (Note 4); 30. Ministry of National Defense; 31. National Palace Museum; 32. Central Election Commission. … 2014 (WT/Let/…) K1 GPA/W/326 Attachment K APPENDIX I CHINESE TAIPEI ANNEX 1 Page 2/2 * In English only. -

Evaluating Art Licensing for Digital Archives Using Fuzzy Integral

mathematics Article Evaluating Art Licensing for Digital Archives Using Fuzzy Integral Yu-Jing Chiu *, Yi-Chung Hu , Jia-Jen Du, Chung-Wei Li and Yen-Wei Ken Department of Business Administration, Chung Yuan Christian University, Chung Li District, Taoyuan City 32023, Taiwan; [email protected] (Y.-C.H.); [email protected] (J.-J.D.); [email protected] (C.-W.L.); [email protected] (Y.-W.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-3-265-5127 Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 9 December 2020; Published: 11 December 2020 Abstract: Determining how to evaluate the art licensing model is a complex multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) problem. This study explores the critical factors influencing art licensing in the art and creative industry because this industry has potential contributions to a high value-added cultural economy in Taiwan. Due to the high cultural value of the National Palace Museum and the uniqueness of its cultural relics, this study takes it as an empirical case. The decision hierarchy is constructed based on a literature review and expert interviews. Furthermore, we used the fuzzy integral to calculate the weights and overall performance of the three licensing models. The empirical results illustrate that both brand licensing and image licensing groups emphasized the aspect of market environment as the primary consideration for licensing model selection. In particular, respondents considered that the adoption of a brand licensing model could facilitate the achievement of better overall performance value. The reason is that brand licensing made the company’s brand visible by imprinting the brand names of both the National Palace Museum and the company on products. -

National Palace Museum

Data-Supporting Partner Introduction National Palace Museum 1 1.Data category enable to provide • Nominal and numerical datasets (artifact metadata, visitor figures, accounting reports) • Open Data (artifact image search and downloads-72 dpi, image downloads-300 dpi, exhibition package downloads ) • Open API (access basic information about the NPM’s collection, obtain a comprehensive list of the NPM’s collection, obtain exhibition and event information lists, etc. Title of the government entities : 2.Where can it be found National Palace Museum •Open Data Service Platform at https://theme.npm.edu.tw/opendata/index.aspx / 3. How to apply/obtain • Users can download the NPM’s images, high resolution images and exhibition packages through the NPM’s Open Data Website. Users are welcome to download all images on this site for free and unlimited use with no applications required. Please refer to the "Open Government Data License, version 1.0" for more information. Users will need to apply for an API key to access the NPM’s Open API. 2 Title of the government entities : 4.Case of using National Palace Museum “Everyday Treasures" NPM Home Interactive Game • In this game, the NPM’s famous artifacts—Northern Song Ding ware Pillow in the Shape of a Recumbent Child and Qing dynasty Jadeite Cabbage—are transformed into limited edition home furnishing products. • With this game, you can decorate your home with the NPM’s ancient collection and integrate the museum’s rare treasures into your everyday surrounding. Emperor Qianlong: NPM Robotic Chat Buddy • Make Emperor Qianlong your chat buddy. • Take personality tests to connect with the artifacts.