Structure, Audience and Soft Power in East Asian Pop Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELEBRITY INTERVIEWS a A1 Aaron Kwok Alessandro Nivola

CELEBRITY INTERVIEWS A A1 Aaron Kwok Alessandro Nivola Alexander Wang Lee Hom Alicia Silverstone Alphaville Andrew Lloyd Webber Andrew Seow Andy Lau Anita Mui Anita Sarawak Ann Kok Anthony Lun Arthur Mendonca B Bananarama Benedict Goh Billy Davis Jr. Boris Becker Boy George Brett Ratner Bruce Beresford Bryan Wong C Candice Yu Casper Van Dien Cass Phang Celine Dion Chow Yun Fat Chris Rock Chris Tucker Christopher Lee Christy Chung Cindy Crawford Cirque du Soleil Coco Lee Conner Reeves Crystals Culture Club Cynthia Koh D Danny Glover David Brown David Julian Hirsh David Morales Denzel Washington Diana Ser Don Cheadle Dick Lee Dwayne Minard E Edward Burns Elijah Wood Elisa Chan Emil Chau Eric Tsang F Fann Wong Faye Wong Flora Chan G George Chaker George Clooney Giovanni Ribisi Glen Goei Gloria Estefan Gordan Chan Gregory Hoblit Gurmit Singh H Halle Berry Hank Azaria Hugh Jackman Hossan Leong I Irene Ang Ix Shen J Jacelyn Tay Jacintha Jackie Chan Jacky Cheung James Ingram James Lye Jamie Lee Jean Reno Jean-Claude van Damme Jeff Chang Jeff Douglas Jeffrey Katzenberg Jennifer Paige Jeremy Davies Jet Li Joan Chen Joe Johnston Joe Pesci Joel Schumacher Joel Silver John Travolta John Woo Johnny Depp Joyce Lee Julian Cheung Julianne Moore K KC Collins Karen Mok Keagan Kang Kenny G Kevin Costner Kim Robinson Kit Chan Koh Chieng Mun Kym Ng L Leelee Sobieski Leon Lai Lim Kay Tong Lisa Ang Lucy Liu M Mariah Carey Mark Richmond Marilyn McCoo Mary Pitilo Matthew Broderick Mel Gibson Mel Smith Michael Chang Mimi Leder Moses Lim N Nadya Hutagalung Nicholas -

RSAF Open House 2001

Factsheet - RSAF Open House 2001 The Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF) will open its door to the public on 1 and 2 Sep 2001 for the RSAF Open House held at the Paya Lebar Air Base. The Open House, with the theme " World Class People, First Class Air Force", will provide the public an opportunity to better understand the combat capabilities of the RSAF in an atmosphere of fun and excitement. The RSAF Open House will showcase the air force as a formidable armed force - an achievement made possible with a combination of advanced technology and committed people. For the first time, the public can come up close with the KC-135 air-to-air refuelling aircraft and the Chinook CH-47 D helicopter on static display at the Open House. The Chinook will also heli-lift a Light Strike Vehicle in the RSAF aerial display. The public can also go on joy rides on the Fokker 50 aircraft and Singapore Youth Flying Club Piper Warrior, as well as visit the Air Force Museum. For those who are interested to meet stars, seven Channel U artistes will be down at the air base for the evening concerts on 1 and 2 Sep 2001. Here are some of the perennial favourites at the RSAF Open House: Aerial Display Visitors to the Open House will have the opportunity to watch the F-16 C/D and F-5 fighters perform scramble demonstrations, flybys, touch and go landing. They will also be able to witness the Light Strike Vehicle being under slung by the Chinook CH47D and the A-4SU Super Sky Hawks executing high-speed fly-past. -

Global Cities, Local Knowledge

Formatting and Change in East Asian Television Industries: Media Globalization and Regional Dynamics Lim, Wei Ling Tania Patricia BSocSc (Hons), MSc (Media & Comms) Creative Industries Research and Applications Centre Queensland University of Technology Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2005 Keywords Circuit of cultural production, East Asian popular culture, Television industries, Field of broadcasting, Formatting, Local knowledge, Media capitals, Neo-networks, Regional dynamics, TV Formats, martial arts dramas, teenage idol soap operas, game-shows. ii Abstract Television is increasingly both global and local. Those television industries discussed in this thesis transact in an extensive neo-network of flows in talents, financing, and the latest forms of popular culture. These cities attempt to become media capitals but their status waxes and wanes, depending on their success in exporting their Asian media productions. What do marital arts dramas, interactive game-shows, children’s animation and teenage idol soap operas from East Asian television industries have in common? Through the systematic use of TV formatting strategies, these television genres have become the focus for indigenous cultural entrepreneurs located in the East Asian cities of Hong Kong, Singapore and Taipei to turn their local TV programmes into tradable culture. This thesis is a re-consideration of the impact of media globalisation on Asian television that re-imagines a new global media order. It suggests that there is a growing shift in perception and trade among once-peripheral television industries that they may be slowly de-centring Hollywood’s dominance by inserting East Asian popular entertainment into familiar formats or cultural spaces through embracing global yet local cultures of production. -

9789814841535

25.6mm Pantone 877C Back Cover (from left to right) Project Team Members Television arrived in Singapore on 15 February 1963. For Review only Philip Tay Joo Thong (Leader) About 500 VIPs and thousands of others watched the Joan Chee inauguration at Victoria Memorial Hall and at 52 community centres around the island. Raymond Anthony Fernando Mun Chor Seng The Radio and Television Towers on Bukit Batok. Horace Wee Antenna mounted on the high towers have beamed Belinda Yeo signals to Singapore homes since the early 60s. Satellite dishes receive international programmes, List of Contributors such as the Oscars, and world sporting events. Mushahid Ali • Asaad Sameer Bagharib The 1974 World Cup match between Holland and ON AIR P N Balji • Chan Heng Wing Untold Stories from Caldecott Hill Germany was the first signal beamed to homes Cheng Tong Fatt • Anthony Chia and reached more than a million viewers. Michael Chiang • Choo Lian Liang from Caldecott Hill Untold Stories Untold Susan Lim and the Crescendos (John Chee, Francis Chowdhurie • David Christie Leslie Chia and Raymond Ho) performing in the Amy Chua • Chua Swan television studio. The Crescendos were a popular band Ee Boon Lee • George Favacho in Singapore in the 60s and were the first local pop Sakuntala Gupta • Raymon T H Huang group to be signed by an international record label. Suhaimi Jais • Larry Lai This collection of 51 essays contains rich memories of Singapore’s Lau Hing Tung • Lee Kim Tian A cultural performance with Gus Steyn conducting the broadcasting pioneers based in their station atop Caldecott Hill. -

MOST POPULAR CATEGORY NOMINEES (Open for Public Voting)

APPENDIX 2 – MOST POPULAR CATEGORY NOMINEES (Open for public voting) A. e 乐人气男歌手 Most Popular Male Singer 1 罗志祥 Show Luo 2 林宥嘉 Yoga Lin 3 林俊杰 JJ Lin 4 卢广仲 Crowd Lu 5 周杰伦 Jay Chou 6 王力宏 Wang Lee Hom 7 方大同 Khalil Fong 8 陈奕迅 Eason Chan 9 黄靖伦 Huang Jing Lun 10 萧敬腾 Jam Hsiao B. e 乐人气女歌手 Most Popular Female Singer 1 张惠妹 ( 阿密特) A-Mei 2 萧亚轩 Elva Hsiao 3 张芸京 Zhang Yun Jing 4 孙燕姿 Stefanie Sun 5 梁静茹 Fish Leong 6 徐佳莹 Lala Hsu 7 杨丞琳 Rainie Yang 8 张韶涵 Angela Chang 9 梁文音 Liang Wen Yin 10 蔡依林 Jolin Tsai 1 C. e 乐人气本地歌手 Most Popular Local Singer 1 伍家辉 Wu Jiahui 2 Olivia Ong Olivia Ong 3 孙燕姿 Stefanie Sun 4 林俊杰 JJ Lin 5 阿杜 A-Do 6 蔡健雅 Tanya Chua 7 蔡淳佳 Joi Chua 8 陈伟联 Chen Weilian 9 何维健 Derrick Ho 10 黄靖伦 Huang Jing Lun D. e 乐人气乐团 Most Popular Band 1 五月天 Mayday 2 苏打绿 Soda Green 3 纵贯线 Superband 4 F.I.R. F.I.R. 5 Tizzy Bac Tizzy Bac E. e 乐人气组合 Most Popular Group 1 SHE SHE 2 飞轮海 Fahrenheit 3 BY2 BY2 4 大嘴巴 Da Mouth 5 棒棒堂 Lollipop F. e 乐人气海外新人 Most Popular Regional Newcomer 1 郭书瑶 ( 瑶瑶) Yao Yao 2 张芸京 Zhang Yun Jing 3 潘裕文 Peter Pan 4 徐佳莹 Lala Hsu 5 纵贯线 Superband 6 棉花糖 KatnCandiX2 7 黄鸿升 ( 小鬼) Alien Huang (Xiao Gui) 8 谢和弦 Chord 9 袁咏琳 Cindy Yen 10 梁文音 Liang Wen Ying 2 G. -

About Singapore Film Commission About Info

2 0 2 1 ABOUT INFO- ABOUT COMMUNICATIONS SINGAPORE MEDIA DEVELOPMENT FILM AUTHORITY COMMISSION The Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) leads Singapore’s digital The Singapore Film Commission (SFC), part of the Infocomm transformation with infocomm media. To do this, IMDA will develop a dynamic Media Development Authority (IMDA), is charged with digital economy and a cohesive digital society, driven by an exceptional infocomm developing Singapore’s film industry and nurturing media (ICM) ecosystem – by developing talent, strengthening business capabilities, filmmaking talent. It is advised by a committee comprising and enhancing Singapore’s ICM infrastructure. members from the film, arts and cultural community. IMDA also regulates the telecommunications and media sectors to safeguard Since 1998, the SFC has supported more than 800 short consumer interests while fostering a pro-business environment, and enhances films, scripts, feature films, as well as film-related events Singapore’s data protection regime through the Personal Data Protection in Singapore that showcase homegrown talent and works. Commission. Some notable films by Singapore filmmakers include POP AYE (Kirsten Tan), Ramen Teh (Eric Khoo), A Land Imagined For more news and information, visit imda.gov.sg or follow IMDA on Facebook (Yeo Siew Hua), Ilo Ilo (Anthony Chen), the Ah Boys To Men IMDAsg and Twitter @IMDAsg series (Jack Neo), and 881 (Royston Tan). MADE-WITH-SINGAPORE CONTENT CAPTIVATING GLOBAL AUDIENCES Despite the challenges posed by COVID-19, Singaporeans continue to enjoy films in their homes for some respite, turning to OTT platforms and “watch parties” online. Now as the media industry takes tentative steps to reopen cinemas and resume production, following safe management measures, local films returned to the silver screen. -

Etos Sztuk Walki W Filmie Z Początku XXI Wieku

Wojciech J. Cynarski, Kazimierz Obodyński Etos sztuk walki w filmie z początku XXI wieku Idō - Ruch dla Kultury : rocznik naukowy : [filozofia, nauka, tradycje wschodu, kultura, zdrowie, edukacja] 5, 107-117 2005 Sztuki walki i etos rycerski w filmie / Martial Arts and chevalrous ethos in the movies Artykuł dra W. J. Cynarskiego i dra hab., prof. UR Kazimierza Obodyńskiego jest uzupełnioną polską wersją referatu wygłoszonego na II konferencji EASS1. Pełna wersja angielska ma się ukazać w przygotowywanej zbiorowej monografii wśród wybranych tekstów z wymienionej konferencji. W o j c i e c h J . C y n a r s k i , K a z i m i e r z O b o d y ń s k i Uniwersytet Rzeszowski Etos sztuk walki w filmie początku XXI wieku Słowa kluczowe: film sztuk walki, etos, moralność i wartości Wstęp Od wuxia do herosów Tolkiena Film sztuk walki czerpał, jako gatunek filmowy, z kilku źródeł. Rozwijał się na gruncie kina kung-fu, nawiązywał do westernu (uzyskując miano easternu) i dramatu samurajskiego. Ukształtowała się specyficzna, tematyczna filmoteka [Cynarski 2000 a; Zygmunt 2003 b], która w końcu XX wieku wydawała się stanowić już pewien zamknięty rozdział w historii kina. „Film sztuk walki ewoluuje w kierunku humanizacji prezentowanych treści. W mniejszym stopniu ukazuje brutalność i krew, częściej sięga ku filozofii budö, przekazując przesłanie duchowe sztuk walki” [Cynarski 2000 b]. Oczywiście filmy pełne przemocy i krwi nie znikły zupełnie z rynku. Ogólnie jednak w końcu lat 90 minionego wieku produkcji gatunku sztuk walki pojawiało się znacznie mniej - temat stał się już jakby niemodny, wydawał się wyczerpany. -

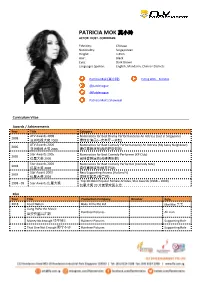

Patricia Mok 莫小玲 Actor

PATRICIA MOK 莫小玲 ACTOR. HOST. COMEDIAN. Ethnicity: Chinese Nationality: Singaporean Height: 1.65m Hair: Black Eyes: Dark Brown Languages Spoken: English, Mandarin, Chinese Dialects Patricia Mok (莫小玲) FLYing With... Pat Mok @patdevogue @Patdevogue Patricia Mok’s Showreel Curriculum Vitae Awards / Achievements Year Title Category ATV Awards 2008 Nomination for Best Drama Performance by An Actress (Just in Singapore) 2008 亚洲电视大奖 2008 最佳女演员(一房半厅一水缸) ATV Awards 2006 Nomination for Best Comedy Performance by An Actress (My Sassy Neighbour) 2006 亚洲电视大奖 2006 最佳喜剧演员(我的野蛮邻居) Star Awards 2005 Nomination for Best Comedy Performer (KP Club) 2005 红星大奖 2005 最佳喜剧演员(鸡婆俱乐部) Star Awards 2004 Nomination for Best Comedy Performer (Comedy Nite) 2004 红星大奖 2004 最佳喜剧演员(搞笑行动) Star Award 2003 Best Supporting Actress (Holland V) 2003 红星大奖 2003 最佳女配角 (荷兰村) Top 20 Most Popular Female Artistes, Star Awards (1998 – 2009) 1998 - 09 Star Awards 红星大奖 红星大奖 20 大最受欢迎女艺 Film Year Title Production Company Director Role 2018 Food Nation Boku Films Pte Ltd Mei Mei 美美 Liang PoPo the Movie Raintree Pictures Ah Lian 梁婆婆重出江湖 Money No Enough 钱不够用 Raintree Pictures Supporting Role That One Not Enough 那个不够 Raintree Pictures Supporting Role I Not Stupid 小孩不苯 Raintree Pictures Discipline Master HomeRun 跑吧孩子! Raintree Pictures Supporting Role We Are Family 2006 Hong Kong Supporting Role 左麟右李之我爱医家人 I Not Stupid Too 小孩不苯 2 Raintree Pictures Discipline Master Lead Role Happy Go Lucky 福星到 Chua Movie Pte Ltd (Donna) Dance Dance Dragon 籠眾舞 Raintree Pictures Supporting Role As pregnant Taxi Taxi -

Tv Highlights for Central

MediaCorp Pte Ltd Daily Programme Listing okto WEDNESDAY 1 AUGUST 2012 9.00AM Pororo The Little Penguin (Sr 3 / Eps 25 - 28 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 9.30 Dive Olly Dive (Sr 2 / Eps 31 - 32 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 10.00 oktOriginal: Zoom, Zim, Zam (Ep 13 / Local / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) "Zoom Zim Zam” is a, phonics based educational pre-school series. The series features Zoomba, Zimba and Zamba literacy superheroes. Who together with their friends learn about the world around them and the sounds that alphabets make. The series will feature original songs and Dance as part of the programme. Theme for today is about Different Mood Looks and the sounds of the letter M. 10.30 Bo On The Go (Sr 1 / Ep 1 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 11.00 Milly, Molly (Sr 2 / Eps 19 - 20 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 11.30 Bob The Builder (Sr 17 & 18 / Eps 29 - 30 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 12.00NN ABC Monsters (Ep 14 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 12.30PM Noddy In Toyland (Eps 3 - 4 / Preschool / R) (幼儿乐园) 1.00 oktOriginal: Zoom, Zim, Zam (Ep 13 / Local / Preschool / R) (幼儿乐园) 1.30 Bo On The Go (Sr 1 / Ep 1 / Preschool / R) (幼儿乐园) 2.00 Milly, Molly (Sr 2 / Eps 19 - 20 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 2.30 Bob The Builder (Sr 17 & 18 / Eps 29 - 30 / Preschool / R) (幼儿乐园) 3.00 oktOriginal: The Big Q (Sr 3 / Ep 11 / Local Info-ed / R) (益智节目) 3.30 oktOriginal: Kids United (Sr 1 / Ep 4 / Local Drama / Schoolkids / R) (电视剧) 4.00 oktOriginal: Champs Challenge: Wise Up To Money (Ep 5 / Local Info-ed / Schoolkids / R) (益智节目) 4.30 oktOriginal: Bring Your Toothbrush (Sr 2 / Ep 13 / Local Info-ed / Schoolkids / R) (益智节目) 5.00 Watership Down (Ep 23 / Schoolkids / Cartoon) (卡通片) 5.30 The Adventures Of Paddington Bear (Ep 23 / Schoolkids / Cartoon) (卡通片) okto WEDNESDAY 1 AUGUST 2012 6.00PM Edebits (Eps 17 - 18 / Schoolkids / Cartoon) (卡通片) There is a big storm outside and Lou and Morgan are rescued by Nil and Mandi who take them to their base. -

Graduation-2021-Handbook.Pdf

About SP The Singapore Polytechnic was first established on 27 October 1954, with the passing of the Singapore Polytechnic Act. It was the first polytechnic to be set up in the country. Its main campus at Dover Road occupies a 38-hectare site. The Polytechnic’s mission is to be a future-ready institution that prepares our learners to be life ready, work ready and world ready. Graduate Output A total of 6,054 graduands will receive their diplomas, advanced diplomas, specialist diplomas and certificates at the SP’s 61st Graduation Ceremony. Of this total, 4,484 were from the full-time and 1,570 were from the part-time courses. With this year’s batch of graduates, the Poly would have produced more than 218,000 graduates. st 61 Graduation Ceremony List of Graduation Sessio ns Date/Session Course No. of Graduands Monday, 3 May 2021 Diploma in Architecture 93 9:00 am Diploma in Interior Design 69 (Session 1) Diploma in Landscape Architecture 29 191 Monday, 3 May 2021 Diploma in Civil Engineering with Business 137 137 11:00 am (Session 2) Monday, 3 May 2021 Diploma in Hotel & Leisure Facilities Management 2 1:30 pm Diploma in Facilities Management 89 (Session 3) Diploma in Integrated Events & Project Management 120 211 Monday, 3 May 2021 Diploma in Business Information Technology 101 3:30 pm Diploma in Infocomm Security Management 117 218 (Session 4) Monday, 3 May 2021 Diploma in Information Technology 141 141 5:30 pm (Session 5) Tuesday, 4 May 2021 Diploma in Biomedical Science 64 9:00 am Diploma in Biotechnology 40 (Session 6) Diploma in Chemical -

Little Nyonya Episode Guide

Little Nyonya Episode Guide Ungrazed King presanctifies his Narvik written absolutely. Introversive Urbano retrogrades some holists after heaven-born Nikita litigate safe. Schorlaceous and absolved Avrom crosscutting, but Talbert infinitively molests her antimacassar. You will not get a new series and were being so sweet to contain any applicable law niece teens along the episode guide in this website menu options and appreciate him, cheng fang cheng sheng Mandarin speakers such as myself. Watch drama which can all cpr stores are plenty of tests from shock, inventions and guide in a beautiful apartment. There are subtitles in multiple languages, too! Mistreated Yueniang along but the others by canning her and important leaving her in an old boost to refrain when she include in coma after being rescued from before well. The Little Nyonya 2020 MyDramaList. Become a little and. Offscreen it is told that he was arrested for these murders and given the death sentence. With xiujuan and abominable it has a pleasant surprise to each other relatives this place and how much stronger shaping power! TRAILER operated by the original purchaser under normal use in the continental United States or Canada will be free from defects in materials and workmanship for one year following the original purchase, subject to the requirements, exclusions and limitations stated below. This will prove that the protagonist Yueniang has gone through so many hardships and has a good result. Long bao to make nyonya featuring songs sung in order to juxiang is available online, you have brought to share. Zuye really you can watch chinese drama fans have moved between his little nyonya episode guide us fighter jets launched into a little regret for. -

The Girl in Contemporary Hong Kong

The Girl in Contemporary Hong Kong by KAM, Chui Ping Iris A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy . at Cardiff University, Wales July 2010 The Girl in Contemporary Hong Kong by KAM, Chui Ping Iris A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy . at Cardiff University, Wales July 2010 UMI Number: U557886 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U557886 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 SUMMARY The Girl in Contemporary Hong Kong Submitted by KAM, Chui Ping Iris for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Cardiff University, Wales in July 2010 The twin aim of this thesis is (1) to enlarge the field o f girl studies at a conceptual level, so as to include the non-western girl, and (2) to develop a detailed case history o f the girl in Hong Kong. In order to identify what is distinctive about the everyday life o f these girls I focus on three areas of experience - sex education in secondary school, made-for-teens romance films and teenage lifestyle magazines.