Michelle S. Simon, Hogan Vs. Gawker II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alex Pareene: Pundit of the Century

Alex Pareene: Pundit of the Century Alex Pareene, first of Wonkette, then Gawker, then Salon, then back to Gawker, then a stillborn First Run Media project, and now Splinter News is a great pundit. In fact, he is a brilliant pundit and criminally underrated. His talent is generally overlooked because he has by-and-large written for outlets derided by both the right and the center. Conservatives have treated Salon as a punching bag for years now, and Gawker—no matter how biting or insightful it got—was never treated as serious by the mainstream because of their willingness to sneer, and even cuss at, the powers that be. If instead Mr. Pareene had been blogging at Mother Jones or Slate for the last ten years, he would be delivering college commencement speeches by now. In an attempt to make the world better appreciate this elucidating polemicist, here are some of his best hits. Mr. Pareene first got noticed, rightfully, for his “Hack List” feature when he was still with Salon. Therein, he took mainstream pundits both “left” and right to task for, well, being idiots. What is impressive about the list is that although it was written years ago, when America’s political landscape was dramatically different from what it is today, it still holds up. In 2012, after noting that while The New York Times has good reporting and that not all of their opinion columns were bad… most of them were. Putting it succinctly: “Ross Douthat is essentially a parody of the sort of conservative Times readers would find palatable, now that David Brooks is a sad shell of his former self, listlessly summarizing random bits of social science and pretending the Republican Party is secretly moderate and reasonable.” Mr. -

Univision Communications Inc to Acquire Digital Media Assets from Gawker Media for $135 Million

UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC TO ACQUIRE DIGITAL MEDIA ASSETS FROM GAWKER MEDIA FOR $135 MILLION Acquisition of Digital Assets will Reinforce UCI’s Digital Strategy and is Expected to Increase Fusion Media Group’s Digital Reach to Nearly 75 Million Uniques, Building on Recent Investments in FUSION, The Root and The Onion NEW YORK – AUGUST 18, 2016 – Univision Communications Inc. (UCI) today announced it has entered into an agreement to acquire digital media assets as part of the bankruptcy proceedings of Gawker Media Group, Inc. and related companies that produce content under a series of original brands that reach nearly 50 million readers per month, according to comScore. UCI will acquire the digital media assets for $135 million, subject to certain adjustments, and these assets will be integrated into Fusion Media Group (FMG), the division of UCI that serves the young, diverse audiences that make up the rising American mainstream. The deal, which will be accounted for as an asset purchase, includes the following digital platforms, Gizmodo, Jalopnik, Jezebel, Deadspin, Lifehacker and Kotaku. UCI will not be operating the Gawker.com site. With this strategic acquisition, FMG’s digital reach is expected rise to nearly 75 million uniques, or 96 million uniques when including its extended network. The acquisition will further enrich FMG’s content offerings across key verticals including iconic platforms focused on technology (Gizmodo), car culture (Jalopnik), contemporary women’s interests (Jezebel) and sports (Deadspin), among others. The deal builds on UCI’s recently announced creation of FMG and investments in FUSION, The Root and The Onion, which includes The A.V. -

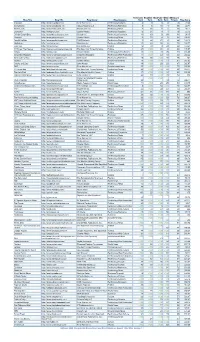

Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Technorati Rank

Technorati Bloglines BlogPulse Wikio SEOmoz’s Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Rank Rank Rank Rank Trifecta Blog Score Engadget http://www.engadget.com Time Warner Inc. Technology/Gadgets 4 3 6 2 78 19.23 Boing Boing http://www.boingboing.net Happy Mutants LLC Technology/Marketing 5 6 15 4 89 33.71 TechCrunch http://www.techcrunch.com TechCrunch Inc. Technology/News 2 27 2 1 76 42.11 Lifehacker http://lifehacker.com Gawker Media Technology/Gadgets 6 21 9 7 78 55.13 Official Google Blog http://googleblog.blogspot.com Google Inc. Technology/Corporate 14 10 3 38 94 69.15 Gizmodo http://www.gizmodo.com/ Gawker Media Technology/News 3 79 4 3 65 136.92 ReadWriteWeb http://www.readwriteweb.com RWW Network Technology/Marketing 9 56 21 5 64 142.19 Mashable http://mashable.com Mashable Inc. Technology/Marketing 10 65 36 6 73 160.27 Daily Kos http://dailykos.com/ Kos Media, LLC Politics 12 59 8 24 63 163.49 NYTimes: The Caucus http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com The New York Times Company Politics 27 >100 31 8 93 179.57 Kotaku http://kotaku.com Gawker Media Technology/Video Games 19 >100 19 28 77 216.88 Smashing Magazine http://www.smashingmagazine.com Smashing Magazine Technology/Web Production 11 >100 40 18 60 283.33 Seth Godin's Blog http://sethgodin.typepad.com Seth Godin Technology/Marketing 15 68 >100 29 75 284 Gawker http://www.gawker.com/ Gawker Media Entertainment News 16 >100 >100 15 81 287.65 Crooks and Liars http://www.crooksandliars.com John Amato Politics 49 >100 33 22 67 305.97 TMZ http://www.tmz.com Time Warner Inc. -

Response Sympathy for the Devil: Gawker, Thiel, And

RESPONSE SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL: GAWKER, THIEL, AND NEWSWORTHINESS AMY GAJDA* At a time when some courts had shifted to protect privacy rights more than press rights, the Gawker website published a grainy and apparently surreptitiously recorded sex tape featuring professional wrestler Hulk Hogan. What the jury that awarded Hulk Hogan more than $140 million in his privacy lawsuit did not know is that Peter Thiel, an individual apparently motivated to bring Gawker down, had helped to bankroll the plaintiff’s case. This Response, inspired by The Weaponized Lawsuit Against the Media: Litigation Funding as a New Threat to Journalism, argues that both sides in the Gawker dispute deserve some level of sympathy. First, Gawker for rejecting at times too restrictive ethics considerations when those considerations can lead to non-reporting that protects the powerful. But it also argues that sympathy is due to Thiel whose parallel motivation was to protect individual privacy at a time when some publishers believed they could publish whatever they wished. It ultimately concludes that caps on damages might best balance important and competing interests between press and privacy. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................ 530 I. Gawker and Its Choices .................................................... 532 A. The Teenager v. Gawker ........................................... 538 B. The Acquitted and Gawker ....................................... 540 * The Class of 1937 Professor of Law, Tulane University Law School. I am grateful to the American University Law Review for soliciting this Response from me and for excellent editing assistance. Thanks also to Chris Edmunds and David Meyer for helpful comments. 529 530 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 67:529 C. Gawker and Hulk Hogan ......................................... -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ------X in Re: : : Chapter 11 GAWKER MEDIA LLC, Et Al., : Case No

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------------X In re: : : Chapter 11 GAWKER MEDIA LLC, et al., : Case No. 16-11700 (SMB) : Debtors. : --------------------------------------------------------X MEMORANDUM DECISION DENYING MOTION TO ENJOIN PLAINTIFFS FROM CONTINUING STATE COURT ACTION AGAINST RYAN GOLDBERG A P P E A R A N C E S: SAUL EWING ARNSTEIN & LEHR LLP 1270 Avenue of the Americas, Suite 2005 New York, NY 10020 Sharon L. Levine, Esq. Dipesh Patel, Esq. Of Counsel — and — WILLIAMS & CONNOLLY LLP 725 Twelfth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20005 Thomas G. Hentoff, Esq. Chelsea T. Kelly, Esq. Of Counsel Co-Counsel to Ryan Goldberg GOLENBOCK EISEMAN ASSOR BELL & PESKOE LLP 711 Third Avenue New York, New York 10017 Jonathan L. Flaxer, Esq. Michael S. Weinstein, Esq. Of Counsel — and — HARDER LLP 132 S. Rodeo Dr., 4th Floor Beverly Hills, California 90212 Dilan A. Esper, Esq. Of Counsel Co-Counsel to Pregame LLC and Randall James Busack1 STUART M. BERNSTEIN United States Bankruptcy Judge: The confirmed Plan in these cases2 included a third-party release in favor of the Debtors’ employees and independent contractors (collectively, the “Providers”) who provided content for publication on the Debtors’ websites (the “Provider Release”). However, the Provider Release only barred lawsuits brought by an entity “that has received or is deemed to have received distributions made under the Plan.”3 In a subsequent state court lawsuit described in In re Gawker Media LLC, 581 B.R. 754 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2017) (“Gawker”), Pregame LLC and Randall James Busack (collectively, the “Plaintiffs”) sued Gizmodo Media Group LLC (“Gizmodo”), the purchaser of substantially all of the Debtors’ assets, and Ryan Goldberg, a Provider, for defamation and related claims based on the Debtors’ publication of an article Goldberg had authored. -

Social Media Joins Forces to Help Put Nick Denton and Gawker out of Business

Social Media Joins Forces To Help Put Nick Denton and Gawker Out of Business The Public, the Courts and Morality agree: Gawker and Nick Denton are a blight on humanity and they serve no positive social function. Now it is official: “Gawker Media and Nick Denton are evil, sick and perverted abusers staffed by mentally deformed children.” So the world, multiple additional lawsuits, and all of the bloggers have set out to terminate Nick Denton. $115 million verdict in Hulk Hogan sex-tape lawsuit could wipe out Gawker Hogan's lawyer: Gawker editor was "playing God" with my client's privacy. by Joe Mullin - • ^ndrew A Florida jury today ordered Gawker Media to pay $115 million for publishing a sex tape showing Terry Bollea, also known as Hulk Hogan, having sex with his friend's wife. The stunning sum, which may have punitive damages added to it, is a life-threatening event for the New York-based network of news and gossip sites. Gawker Media was one of the first successful, large, digital-only news companies. The final sum is even more than the $100 million Bollea was seeking. Bollea also sued Gawker founder Nick Denton and former editor Albert Daulerio, and the jury found those two men personally liable as well. The sex tape was made about a decade ago, during a period in which the professional wrestler Hogan testified that he was going through a difficult phase with his then-wife. Todd Clem, a Florida radio personality who later legally changed his name to Bubba the Love Sponge, encouraged Hogan to sleep with his wife Heather. -

3 PM 8 Journalism Should Not Be Sponsored

The Society of Professional Journalists Board of Directors Zoom Meeting Feb. 1, 2020 Noon – 3 p.m. EST Improving and Protecting Journalism Since 1909 The Society of Professional Journalists is the nation’s largest and most broad-based journalism organization, dedicated to encouraging the free practice of journalism and stimulating high standards of ethical behavior. Founded in 1909 as Sigma Delta Chi, SPJ promotes the free flow of information vital to a well-informed citizenry, works to inspire and educate the next generation of journalists, and protects First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech and press. AGENDA SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING DATE: FEB. 1, 2020 TIME: NOON-3 P.M. EST JOIN VIA ZOOM AT https://zoom.us/j/250975465 (Meeting ID # 250 975 465) 1. Call to order – Newberry 2. Roll call – Aguilar • Patricia Gallagher Newberry • Matt Hall • Rebecca Aguilar • Lauren Bartlett • Erica Carbajal • Tess Fox • Taylor Mirfendereski • Mike Reilley • Yvette Walker • Andy Schotz (parliamentarian) 3. Minutes from meetings of 10/19/19 and 11/3/19 – Newberry 4. President’s report (attached) – Newberry 5. Executive director’s report (attached) – John Shertzer 6. Update on Strategic Planning Task Force (attached) – Hall 7. Update on EIJ Sponsorship Task Force (attached) – Nerissa Young 8. First Quarter FY20 report (attached) – Shertzer 9. Update on EIJ20 planning – Shertzer/Newberry 10. Committee reports: • Awards & Honors Committee (attached) – Sue Kopen Katcef • Membership Committee (attached) – Colin DeVries • FOI Committee (attached) – Paul Fletcher • Bylaws Committee (attached) – Bob Becker 11. Public comment Enter Executive Session 1 12. SPJ partnership agreements 13. Data management contract 14. -

Personal Foul? Deadspin and an Iconic Athlete CSJ

CSJ- 12- 0042.0 • • Personal Foul? Deadspin and an Iconic Athlete In the early 21st century, the simultaneous surge of celebrities and nonstop demand for content from digital news websites created a new world in sports journalism. Stories that traditional sports reporters and editors often rejected—either for ethical reasons or for lack of interest or evidence—became fodder for sports blogs (many written by fans) and other websites, including those of mainstream newspapers, magazines and television networks. The Internet with its 24/7 news cycle ramped up the race to break news first. Increasingly, gossip and innuendo became accepted as news in its own right. Sports editors had to find ways to compete while trying to maintain editorial standards. Enter Deadspin, a sports blog launched by Gawker Media in 2005. Like many sportswriters dating back to the 1960s, Deadspin shunned the accepted narrative of athletes as heroes. For Deadspin bloggers, however, digging into the off-the-field behavior of athletes was standard fare. Readers loved it. In 2009, the website attracted upwards of 2 million visitors a month. In February 2010, Deadspin Editor A.J. Daulerio learned that celebrated football quarterback Brett Favre, while with the New York Jets, in 2008 had sent cellphone photos of his genitalia to Jenn Sterger, an in-house sideline reporter for the Jets. Favre had been named the National Football League’s Most Valuable Player three times. Throughout his legendary career, Favre had built his image and reputation on being a family man (he was married, with two daughters and a grandchild) and as a sponsor of many charities. -

What Blogs Cost American Business

WHAT BLOGS COST AMERICAN BUSINESS Welcome, S Bradley Search / Interactive News (if this is not you, click Oct. 24, 2005 QwikFIND here) Home » Request Reprints News Hispanic Marketing [Interactive News] Media News Account Action American Demographics WHAT BLOGS COST AMERICAN BUSINESS Data Center In 2005, Employees Will Waste 551,000 Years Career Center Reading Them Marketplace October 24, 2005 My AdAge QwikFIND ID: AAR05Y Print Edition Customer Services By Bradley Johnson Contact Us Media Kit LOS ANGELES (AdAge.com) -- Blog this: U.S. workers in 2005 will waste Privacy Statement the equivalent of 551,000 years reading blogs. Account Intelligence AdCritic.com About 35 million workers -- one in four Agency Preview people in the labor force -- visit blogs Madison+Vine and on average spend 3.5 hours, or Point 9%, of the work week engaged with Encyclopedia them, according to Advertising Age’s AdAgeChina analysis. Time spent in the office on non-work blogs this year will take up the equivalent of 2.3 million jobs. Forget lunch breaks -- blog readers essentially take a daily 40-minute blog break. Bogged down in blogs Currently, the time employees spend While blogs are becoming an accepted reading non-work blogs is the equivalent part of the media sphere, and are of 2.3 million jobs. increasingly being harnessed by marketers -- American Express last week paid a handful of bloggers to discuss small business, following other marketers like General Motors Corp. and Microsoft Corp. into the blogosphere -- they are proving to be competition for traditional media messages and are sapping employees’ time. http://adage.com/news.cms?newsId=46494 (1 of 4)10/24/2005 3:55:17 PM WHAT BLOGS COST AMERICAN BUSINESS Case in point: Gawker Media, blog home of Gawker (media), Wonkette (politics) and Fleshbot (porn). -

PR Pros Urge Gawker to Stay True to Itself

PR pros urge Gawker to stay true to itself By Sean Czarnecki August 17, 2016 The Nick Denton-founded media company struck a deal this week to be bought by Univision amid long- running legal disputes with billionaire Trump supporter Peter Thiel - the fate of its flagship publication, Gawker.com, remains unknown. NEW YORK: Univision is snapping up Gawker for $135 million following a bidding process that concluded Tuesday evening, potentially adding all seven of its brands to a portfolio that already includes Fusion, The Onion, and The Root. Apart from its flagship Gawker.com website, Nick Denton's company also operates Deadspin, Gizmodo, Jalopnik, Jezebel, Kotaku, and Lifehacker. But according to PR pros operating in the tech space who spoke to PRWeek, the jury is still out on whether the irreverent brand will be able to retain its character, or even if Gawker.com will continue to operate, under a Univision umbrella that would link it to Fusion, a network it openly mocked in the past. "Univision has to recognize [Gawker's edginess and editorial freedom] is an essential ingredient to bringing in the demographic they’re seeking," says Peter Himler, founding principal of Flatiron Communications, who previously served as chief media officer for Edelman worldwide and headed Burson-Marsteller’s U.S. corporate and strategic media team. "It would be unwise to demand Gawker tone it down," he adds. "On the other hand, it doesn’t want to be the object of a liability suit. It will likely put on some restraints, but it won’t want to mess too much with the content." Demographic reach was one thing Gawker founder Nick Denton focused on in a statement to media outlets regarding the deal, saying Univision is "rapidly assembling the leading digital media group for millennial and multicultural audiences." Attempts to contact Denton were unsuccessful as of press time. -

Infographic by Ben Fry; Data by Technorati There Are Upwards of 27 Million Blogs in the World. to Discover How They Relate to On

There are upwards of 27 million blogs in the world. To discover how they relate to one another, we’ve taken the most-linked-to 50 and mapped their connections. Each arrow represents a hypertext link that was made sometime in the past 90 days. Think of those links as votes in an endless global popularity poll. Many blogs vote for each other: “blogrolling.” Some top-50 sites don’t have any links from the others shown here, usually because they are big in Japan, China, or Europe—regions still new to the phenomenon. key tech politics gossip other gb2312 23. Fark gouy2k 13. Dooce huangmj 22. Kottke 24. Gawker 40. Xiaxue 2. Engadget 4. Daily Kos 6. Gizmodo 12. SamZHU para Blogs 41. Joystiq 44. nosz50j 3. PostSecret 29. Wonkette 39. Eschaton 1. Boing Boing 7. InstaPundit 17. Lifehacker 25. chattie555 com/msn-sa 14. Beppe Grillo 18. locker2man 27. spaces.msn. 34. A List Apart 37. Power Line 16. Herramientas 43. AMERICAblog 20. Think Progress 35. manabekawori 49. The Superficial 9. Crooks and Liars11. Michelle Malkin 28. lwhanz198153030. shiraishi31. The seesaa Space Craft 50. Andrew Sullivan 19. Open Palm! silicn 33. spaces.msn.com/ 45. Joel46. on spaces.msn.com/Software 5. The Huffington Post 8. Thought Mechanics 15. theme.blogfa.com 21. Official Google Blog 38. Weebl’s Stuff News 47. princesscecicastle 32. Talking Points Memo 48. Google Blogoscoped 42. Little Green Footballs 26. spaces.msn. c o m/ 36. spaces.msn.com/atiger 10. spaces.msn.com/klcintw 1. Boing Boing A herald from the 6. -

Univision Communications Inc. Announces 2017 Fourth Quarter Results

PRESS RELEASE UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC. Page 1 of 19 UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC. ANNOUNCES 2017 FOURTH QUARTER RESULTS TOTAL REVENUE OF $780.7 MILLION COMPARED TO $846.5 MILLION TOTAL CORE REVENUE OF $746.7 MILLION COMPARED TO $768.9 MILLION NET INCOME OF $386.7 MILLION COMPARED TO NET INCOME OF $108.0 MILLION ADJUSTED OIBDA OF $347.0 MILLION COMPARED TO $390.1 MILLION ADJUSTED CORE OIBDA OF $316.4 MILLION COMPARED TO $323.0 MILLION NEW YORK, NY – February 15, 2018 – Univision Communications Inc. (the “Company”), the leading media company serving Hispanic America, today announced financial results for the fourth quarter and year ended December 31, 2017. Fourth Quarter 2017 Results Compared to Fourth Quarter 2016 Results • Total revenue decreased 7.8% to $780.7 million from $846.5 million. Total core revenue1 decreased 2.9% to $746.7 million from $768.9 million. • Net income attributable to Univision Communications Inc.2 was $386.7 million compared to $108.0 million. • Adjusted OIBDA3 decreased 11.0% to $347.0 million from $390.1 million. Adjusted Core OIBDA4 decreased 2.0% to $316.4 million from $323.0 million. • Interest expense decreased to $98.4 million from $115.0 million. • The Company continued to deleverage and has reduced total indebtedness, net of cash and cash equivalents by $155.7 million for the fourth quarter of 2017. Full Year 2017 Results Compared to Full Year 2016 Results • Total revenue decreased 0.8% to $3,016.4 million from $3,042.0 million. Total core revenue increased 2.6% to $2,906.8 million from $2,832.2 million.