Street & Smith's Sports Business Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

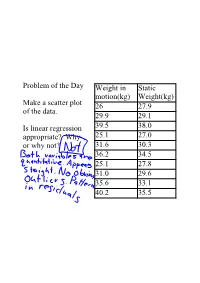

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Lot# Title Bids Sale Price 1

Huggins and Scott'sAugust 7, 2014 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Ultimate 1974 Topps Baseball Experience: #1 PSA Graded Master, Traded & Team Checklist Sets with (564) PSA12 10,$ Factory82,950.00 Set, Uncut Sheet & More! [reserve met] 2 1869 Peck & Snyder Cincinnati Red Stockings (Small) Team Card SGC 10—First Baseball Card Ever Produced!22 $ 16,590.00 3 1933 Goudey Baseball #106 Napoleon Lajoie—PSA Authentic 21 $ 13,035.00 4 1908-09 Rose Co. Postcards Walter Johnson SGC 45—First Offered and Only Graded by SGC or PSA! 25 $ 10,072.50 5 1911 T205 Gold Border Kaiser Wilhelm (Cycle Back) “Suffered in 18th Line” Variation—SGC 60 [reserve not met]0 $ - 6 1915 E145 Cracker Jack #30 Ty Cobb PSA 5 22 $ 7,702.50 7 (65) 1909-11 T206 White Border Singles with (40) Graded Including (4) Hall of Famers 16 $ 2,370.00 8 (37) 1909-11 T206 White Border PSA 1-4 Graded Cards with Willis 8 $ 1,125.75 9 (5) 1909-11 T206 White Borders PSA Graded Cards with Mathewson 9 $ 711.00 10 (3) 1911 T205 Gold Borders with Mordecai Brown, Walter Johnson & Cy Young--All SGC Authentic 12 $ 711.00 11 (3) 1909-11 T206 White Border Ty Cobb SGC Authentic Singles--Different Poses 14 $ 1,777.50 12 1909-11 T206 White Borders Walter Johnson (Portrait) & Christy Mathewson (White Cap)--Both SGC Authentic 9 $ 444.38 13 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Green Portrait) SGC 55 12 $ 3,555.00 14 1909-11 T205 & T206 Hall of Famers with Lajoie, Mathewson & McGraw--All SGC Graded 12 $ 503.63 15 (4) 1887 N284 Buchner Gold Coin SGC 60 Graded Singles 4 $ 770.25 16 (6) -

BEN MCDONALD'sauthenticity

bring your kids ages 9 and under for free PA GE major sporting events that should happen in baltimore 244 05.18 BEN MCDONALD’S authenticity has made him a fan-favorite for years, however, his transition from player to commentator was anything but seamless BY KEVIN ECK > Page 16 photography > courtesy of the baltimore orioles of the baltimore photography > courtesy VISIT BUYATOYOTA.COM FOR GREAT DEALS! buyatoyota.com UPCOMING PROMOTIONS AT ORIOLE PARK may 31- vs. May vs. 15-16 June 3 MAY 16 JUNE 1 FRIDAY FIREWORKS & MUSIC FIELD TRIP DAY POSTGAME, ALL FANS PRESENTED BY WJZ-TV PRE-REGISTERED STUDENTS STUDENT NIGHT ALL STUDENTS, SUBJECT TO AVAILABILITY JUNE 2 THE SANDLOT MOVIE NIGHT May POSTGAME, ALL FANS SPECIAL TICKET PACKAGES AVAILABLE vs. 28-30 JUNE 3 MAY 28 KIDS RUN THE BASES PRESENTED BY WEIS MARKETS ORIOLES MEMORIAL DAY T-SHIRT POSTGAME, ALL KIDS AGES 4-14 ALL FANS MAY 30 ORIOLES COOLER BACKPACK June vs. PRESENTED BY VISIT SARASOTA FIRST 20,000 FANS 15 & OVER 11-13 JUNE 12 DYLAN BUNDY BOBBLEHEAD FIRST 25,000 FANS 15 & OVER bring your kids ages 9 and under for free Issue 244 • 5.15.18 - table of contents - COVER STORY Ben’s Second Act......................................................16 Ben McDonald’s authenticity has made him a fan-favorite for years, however, his transition from player to commentator was anything but seamless By Kevin Eck play, FEATURE STORIES meet stay Sports Business w/ Baltimore Business Journal...... 08 Maryland Gaming w/ Bill Ordine ............................12 Ravens Report w/ Bo Smolka.................................... 13 Orioles Report w/ Rich Dubroff............................. -

Sports Publishing Fall 2018

SPORTS PUBLISHING Fall 2018 Contact Information Editorial, Publicity, and Bookstore and Library Sales Field Sales Force Special Sales Distribution Elise Cannon Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. Two Rivers Distribution VP, Field Sales 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor Ingram Content Group LLC One Ingram Boulevard t: 510-809-3730 New York, NY 10018 e: [email protected] t: 212-643-6816 La Vergne, TN 37086 f: 212-643-6819 t: 866-400-5351 e: [email protected] Leslie Jobson e: [email protected] Field Sales Support Manager t: 510-809-3732 e: [email protected] International Sales Representatives United Kingdom, Ireland & Australia, New Zealand & India South Africa Canada Europe Shawn Abraham Peter Hyde Associates Thomas Allen & Son Ltd. General Inquiries: Manager, International Sales PO Box 2856 195 Allstate Parkway Ingram Publisher Services UK Ingram Publisher Services Intl Cape Town, 8000 Markham, ON 5th Floor 1400 Broadway, Suite 520 South Africa L3R 4T8 Canada 52–54 St John Street New York, NY, 10018 t: +27 21 447 5300 t: 800-387-4333 Clerkenwell t: 212-581-7839 f: +27 21 447 1430 f: 800-458-5504 London, EC1M 4HF e: shawn.abraham@ e: [email protected] e: [email protected] e: IPSUK_enquiries@ ingramcontent.com ingramcontent.co.uk India All Other Markets and Australia Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd. General International Enquiries Ordering Information: NewSouth Books 7th Floor, Infinity Tower C Ingram Publisher Services Intl Grantham Book Services Orders and Distribution DLF Cyber City, Phase - III 1400 Broadway, -

Senate Boosts Defense Budget Saucier

dnmwrttntt Bail}} (ttampua Serving Storrs Since 1896 Vol. LXXXVII No. 43 The University of Connecticut Tuesday, November 8, 1983 Shiites' fire None injured in bomb hits Marines; blast at U.S. Capitol airport closed WASHINGTON (AP) —A was in support of all nations' BEIRUT (AP) _ Shiite bomb exploded Monday night struggle against US. military Moslem gunmen fought Leba- near the Senate chamber in- action and was in reaction to nese soldiers near U.S. mili- side the U.S. Capitol Building, the U.S.-led invasion of Gre- tary positions Monday, police reported. nada and the presence of wounding a Marine and forc- Marines in Lebanon, Saucier There were no reports of said. ing authorities to close the air- injuries in the blast, which one Laurie Santos, a passerby, port for the first time since a witness said described as "a truce took affect six weeks big heavy clap of thunder" said she was three blocks ago. about 11 p.m. EST. from the Capitol when she heard an explosion that soun- The Syrian government A group calling itself the ordered a full mobilization of ded like "a big heavy clap of Armed Resistance Unit claimed thunder" about 11 pjn. EST. its 220,000-man army, saying responsibility for the explo- it feared an attack from the sion and said it was in reaction She said that seconds later, United States or Israel. But the to the U.S. invasion of Grena- she saw smoke coming from Americans and Israelis said These missiles are part of a military parade in Moscow da and the presence of U.S. -

BASE BOWMAN ICONS PROSPECTS 1 Wander Franco

BASE BOWMAN ICONS PROSPECTS 1 Wander Franco Tampa Bay Rays™ 4 Cristian Pache Atlanta Braves™ 5 Matt Manning Detroit Tigers® 7 Casey Mize Detroit Tigers® 9 Dylan Carlson St. Louis Cardinals® 10 Sixto Sanchez Miami Marlins® 11 JJ Bleday Miami Marlins® 13 Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® 14 Jasson Dominguez New York Yankees® 17 Nick Madrigal Chicago White Sox® 18 Royce Lewis Minnesota Twins® 19 Jo Adell Angels® 22 MacKenzie Gore San Diego Padres™ 26 Julio Rodriguez Seattle Mariners™ 27 Adley Rutschman Baltimore Orioles® 28 Nate Pearson Toronto Blue Jays® 30 CJ Abrams San Diego Padres™ 32 Nolan Gorman St. Louis Cardinals® 34 Jarred Kelenic Seattle Mariners™ 37 Forrest Whitley Houston Astros® 38 Marco Luciano San Francisco Giants® 39 Bobby Witt Jr. Kansas City Royals® 44 Andrew Vaughn Chicago White Sox® 46 Joey Bart San Francisco Giants® 50 Riley Greene Detroit Tigers® BOWMAN ICONS ROOKIES 2 Luis Robert Chicago White Sox® Rookie 3 Justin Dunn Seattle Mariners™ Rookie 6 Bobby Bradley Cleveland Indians® Rookie 8 Yoshi Tsutsugo Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 12 Aaron Civale Cleveland Indians® Rookie 15 Trent Grisham San Diego Padres™ Rookie 16 Dustin May Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 20 A.J. Puk Oakland Athletics™ Rookie 21 Nico Hoerner Chicago Cubs® Rookie 23 Sean Murphy Oakland Athletics™ Rookie 24 Yordan Alvarez Houston Astros® Rookie 25 Jordan Yamamoto Miami Marlins® Rookie 29 Michel Baez San Diego Padres™ Rookie 31 Shun Yamaguchi Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 33 Anthony Kay Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 35 Brusdar Graterol Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 36 Bo -

The BG News February 13, 1987

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-13-1987 The BG News February 13, 1987 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 13, 1987" (1987). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4620. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4620 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Spirits and superstitions in Friday Magazine THE BG NEWS Vol. 69 Issue 80 Bowling Green, Ohio Friday, February 13,1987 Death Funding cut ruled for 1987-88 Increase in fees anticipated suicide by Mike Amburgey said. staff reporter Dalton said the proposed bud- get calls for $992 million Man kills wife, The Ohio Board of Regents statewide in educational subsi- has reduced the University's dies for 1987-88, the same friend first instructional subsidy allocation amount funded for this year. A for 1987-88 by $1.9 million, and 4.7 percent increase is called for by Don Lee unless alterations are made in in the academic year 1988-89 Governor Celeste's proposed DALTON SAID given infla- wire editor budget, University students tionary factors, the governor's could face at least a 25 percent budget puts state universities in The manager of the Bowling instructional fee increase, a difficult place. -

2010 Topps Baseball Set Checklist

2010 TOPPS BASEBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Prince Fielder 2 Buster Posey RC 3 Derrek Lee 4 Hanley Ramirez / Pablo Sandoval / Albert Pujols LL 5 Texas Rangers TC 6 Chicago White Sox FH 7 Mickey Mantle 8 Joe Mauer / Ichiro / Derek Jeter LL 9 Tim Lincecum NL CY 10 Clayton Kershaw 11 Orlando Cabrera 12 Doug Davis 13 Melvin Mora 14 Ted Lilly 15 Bobby Abreu 16 Johnny Cueto 17 Dexter Fowler 18 Tim Stauffer 19 Felipe Lopez 20 Tommy Hanson 21 Cristian Guzman 22 Anthony Swarzak 23 Shane Victorino 24 John Maine 25 Adam Jones 26 Zach Duke 27 Lance Berkman / Mike Hampton CC 28 Jonathan Sanchez 29 Aubrey Huff 30 Victor Martinez 31 Jason Grilli 32 Cincinnati Reds TC 33 Adam Moore RC 34 Michael Dunn RC 35 Rick Porcello 36 Tobi Stoner RC 37 Garret Anderson 38 Houston Astros TC 39 Jeff Baker 40 Josh Johnson 41 Los Angeles Dodgers FH 42 Prince Fielder / Ryan Howard / Albert Pujols LL Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Marco Scutaro 44 Howie Kendrick 45 David Hernandez 46 Chad Tracy 47 Brad Penny 48 Joey Votto 49 Jorge De La Rosa 50 Zack Greinke 51 Eric Young Jr 52 Billy Butler 53 Craig Counsell 54 John Lackey 55 Manny Ramirez 56 Andy Pettitte 57 CC Sabathia 58 Kyle Blanks 59 Kevin Gregg 60 David Wright 61 Skip Schumaker 62 Kevin Millwood 63 Josh Bard 64 Drew Stubbs RC 65 Nick Swisher 66 Kyle Phillips RC 67 Matt LaPorta 68 Brandon Inge 69 Kansas City Royals TC 70 Cole Hamels 71 Mike Hampton 72 Milwaukee Brewers FH 73 Adam Wainwright / Chris Carpenter / Jorge De La Ro LL 74 Casey Blake 75 Adrian Gonzalez 76 Joe Saunders 77 Kenshin Kawakami 78 Cesar Izturis 79 Francisco Cordero 80 Tim Lincecum 81 Ryan Theroit 82 Jason Marquis 83 Mark Teahen 84 Nate Robertson 85 Ken Griffey, Jr. -

The Norman J. Hubner Athletic Hall of Fame

THE NORMAN J. HUBNER ATHLETIC HALL OF FAME Ron “Doc” Reed was one of the finest three-sport athletes ever produced at LaPorte High School. Standing 6-6, he made a great target as a football end, was an excellent scorer and rebounder in basketball and a power pitcher in baseball. After graduating from LPHS in 1961, he attended the University of Notre Dame to play basketball and baseball and had a particularly outstanding career on the hardwood. In 1965 Reed signed a contract with the Milwaukee Braves - who later moved to Atlanta, Ga. - as a free agent and had a brief minor league career. From 1965-67 he also filled the key sixth-man role for the Detroit Pistons and could have had a successful NBA career had he not chosen to concentrate on baseball. He made his debut for the Braves on Sept. 26, 1966. In 1968 he made the National League All-Star team and in 1969 he had his best-ever record (18-10), helping Atlanta win its first division title. On April 8, 1974 he was the winning pitcher as Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s record with his 715th career home run. He spent part of 1975 with the St. Louis Cardinals. He then had eight very successful years as a relief pitcher with the Philadelphia Phillies. A fierce competitor, he had 17 saves and a brilliant 2.23 ERA in 1978. One year later he led the majors with 13 wins in relief. He was a key member of the Phillies’ 1980 World Series champions and the 1983 World Series runner-up. -

JOE MAUER DAY •Q"Esgs0 G•Ltair-Ci`

STATE of MINNESOTA WHEREAS: Joseph Patrick Mauer was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota on April 19, 1983; and WHEREAS: Upon graduating from high school, Joe was selected by the Minnesota Twins as the number one overall pick in the first round of the 2001 Major League Baseball First-Year Player Draft; and WHEREAS: On April 5, 2004, Joe made his Major League debut at the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome, going 2-for-3 with two walks in the Twins' 7-4 victory over the Cleveland Indians; and WHEREAS: He became the first catcher to ever win the American League batting title, won three AL batting crowns overall, was a six-time AL All-Star, earned five Louisville Slugger "Silver Slugger Awards" and three Rawlings Gold Glove Awards, and was the 2009 AL Most Valuable Player; and WHEREAS: Joe spent his entire 15-year Major League career with the Minnesota Twins, and on September 30, 2018, he played his final game, retiring with a career .306 batting average, 2,123 hits, 428 doubles, 30 triples, 143 home runs, 923 RBI, 1,018 runs scored, and 939 walks; and WHEREAS: Joe ranks first in Minnesota Twins history for doubles, times on base, and games played as catcher; second in games played, hits, and walks; third in batting average, runs and total bases; fifth in RBI; and eleventh in home runs; and WHEREAS: Joe and his wife, Maddie, are active community leaders, annually hosting fundraisers and volunteering countless hours to various charities throughout Twins Territory; and WHEREAS: In 2019, Joe will become the eighth Minnesota Twin to have his number retired by the organization, joining Harmon Killebrew, Rod Carew, Tony Oliva, Kent Hrbek, Kirby Puckett, Bert Blyleven, and Tom Kelly. -

LOT# TITLE BIDS SALE PRICE* 1 1909 E102 Anonymous Christy Mat(T)

Huggins and Scott's December 12, 2013 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE* 1 1909 E102 Anonymous Christy Mat(t)hewson PSA 6 17 $ 5,925.00 2 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Bat Off Shoulder) with Piedmont Factory 42 Back—SGC 60 17 $ 5,628.75 3 Circa 1892 Krebs vs. Ft. Smith Team Cabinet (Joe McGinnity on Team) SGC 20 29 $ 2,607.00 4 1887 N690 Kalamazoo Bats Smiling Al Maul SGC 30 8 $ 1,540.50 5 1914 T222 Fatima Cigarettes Rube Marquard SGC 40 11 $ 711.00 6 1916 Tango Eggs Hal Chase PSA 7--None Better 9 $ 533.25 7 1887 Buchner Gold Coin Tim Keefe (Ball Out of Hand) SGC 30 4 $ 272.55 8 1905 Philadelphia Athletics Team Postcard SGC 50 8 $ 503.63 9 1909-16 PC758 Max Stein Postcards Buck Weaver SGC 40--Highest Graded 12 $ 651.75 10 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folder Ty Cobb/Desperate Slide for Third PSA 3 11 $ 592.50 11 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Cleveland Americans PSA 5 with Joe Jackson 9 $ 1,303.50 12 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Brooklyn Nationals PSA 5 7 $ 385.13 13 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card St. Louis Nationals PSA 4 5 $ 474.00 14 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Boston Americans PSA 3 2 $ 325.88 15 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card New York Nationals PSA 2.5 with Thorpe 5 $ 296.25 16 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Pittsburgh Nationals PSA 2.5 13 $ 474.00 17 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Detroit Americans PSA 2 16 $ 592.50 18 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Boston Nationals PSA 1.5 7 $ 651.75 19 1913 T200 Fatima Team Cards of Philadelphia & Pittsburgh Nationals--Both PSA 6 $ 272.55 20 (4) 1913 T200 Fatima Team Cards--All PSA 2.5 to 3 11 $ 770.25 -

Exploiting Pitcher Decision-Making Using Reinforcement Learning” (DOI: 10.1214/13-AOAS712SUPP; .Pdf)

The Annals of Applied Statistics 2014, Vol. 8, No. 2, 926–955 DOI: 10.1214/13-AOAS712 c Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2014 MONEYBaRL: EXPLOITING PITCHER DECISION-MAKING USING REINFORCEMENT LEARNING By Gagan Sidhu∗,† and Brian Caffo‡ General Analytics∗1, University of Alberta† and Johns Hopkins University‡ This manuscript uses machine learning techniques to exploit base- ball pitchers’ decision making, so-called “Baseball IQ,” by modeling the at-bat information, pitch selection and counts, as a Markov De- cision Process (MDP). Each state of the MDP models the pitcher’s current pitch selection in a Markovian fashion, conditional on the information immediately prior to making the current pitch. This in- cludes the count prior to the previous pitch, his ensuing pitch selec- tion, the batter’s ensuing action and the result of the pitch. The necessary Markovian probabilities can be estimated by the rel- evant observed conditional proportions in MLB pitch-by-pitch game data. These probabilities could be pitcher-specific, using only the data from one pitcher, or general, using the data from a collection of pitchers. Optimal batting strategies against these estimated conditional dis- tributions of pitch selection can be ascertained by Value Iteration. Optimal batting strategies against a pitcher-specific conditional dis- tribution can be contrasted to those calculated from the general con- ditional distributions associated with a collection of pitchers. In this manuscript, a single season of MLB data is used to cal- culate the conditional distributions to find optimal pitcher-specific and general (against a collection of pitchers) batting strategies. These strategies are subsequently evaluated by conditional distributions cal- culated from a different season for the same pitchers.