Zoogeography of Reptiles and Amphibians in the Intermountain Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Checklist and Distribution Maps of the Amphibians and Reptiles of South Dakota

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies Nebraska Academy of Sciences 2000 A Checklist and Distribution Maps of the Amphibians and Reptiles of South Dakota Royce E. Ballinger University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Justin W. Meeker University of Nebraska-Lincoln Marcus Thies University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas Part of the Life Sciences Commons Ballinger, Royce E.; Meeker, Justin W.; and Thies, Marcus, "A Checklist and Distribution Maps of the Amphibians and Reptiles of South Dakota" (2000). Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies. 49. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas/49 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Academy of Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societiesy b an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 2000. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences, 26: 29-46 A CHECKLIST AND DISTRIBUTION MAPS OF THE AMPmBIANS AND REPTILES OF SOUTH DAKOTA Royce E. Ballinger, Justin W. Meeker, and Marcus Thies School of Biological Sciences University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, Nebraska 68588-0118 rballinger1 @ unl.edu lent treatise on the distribution and ecology of the ABSTRACT turtles of the state in an unpublished dissertation. Fourteen species of amphibians and 30 species of reptiles Several other authors (Dunlap 1963, 1967, O'Roke 1926, are documented from South Dakota, based on the examina Peterson 1974, Smith 1963a, 1963b, 1966, Underhill tion of 7,361 museum specimen records. -

The Walker Basin, Nevada and California: Physical Environment, Hydrology, and Biology

EXHIBIT 89 The Walker Basin, Nevada and California: Physical Environment, Hydrology, and Biology Dr. Saxon E. Sharpe, Dr. Mary E. Cablk, and Dr. James M. Thomas Desert Research Institute May 2007 Revision 01 May 2008 Publication No. 41231 DESERT RESEARCH INSTITUTE DOCUMENT CHANGE NOTICE DRI Publication Number: 41231 Initial Issue Date: May 2007 Document Title: The Walker Basin, Nevada and California: Physical Environment, Hydrology, and Biology Author(s): Dr. Saxon E. Sharpe, Dr. Mary E. Cablk, and Dr. James M. Thomas Revision History Revision # Date Page, Paragraph Description of Revision 0 5/2007 N/A Initial Issue 1.1 5/2008 Title page Added revision number 1.2 “ ii Inserted Document Change Notice 1.3 “ iv Added date to cover photo caption 1.4 “ vi Clarified listed species definition 1.5 “ viii Clarified mg/L definition and added WRPT acronym Updated lake and TDS levels to Dec. 12, 2007 values here 1.6 “ 1 and throughout text 1.7 “ 1, P4 Clarified/corrected tui chub statement; references added 1.8 “ 2, P2 Edited for clarification 1.9 “ 4, P2 Updated paragraph 1.10 “ 8, Figure 2 Updated Fig. 2007; corrected tui chub spawning statement 1.11 “ 10, P3 & P6 Edited for clarification 1.12 “ 11, P1 Added Yardas (2007) reference 1.13 “ 14, P2 Updated paragraph 1.14 “ 15, Figure 3 & P3 Updated Fig. to 2007; edited for clarification 1.15 “ 19, P5 Edited for clarification 1.16 “ 21, P 1 Updated paragraph 1.17 “ 22, P 2 Deleted comma 1.18 “ 26, P1 Edited for clarification 1.19 “ 31-32 Clarified/corrected/rearranged/updated Walker Lake section 1.20 -

(1-5) Or LPN Proposed FY Timeframe Curre

National Listing Workplan 7-Year Workplan (September 2016 Version) 12M: 12-month finding on a petition to list a species. If listing is warranted, we generally intend to proceed with a concurrent proposed Key to Action Types- listing rule and proposed critical habitat designation, if critical habitat is prudent and determinable. Discretionary Status Review: Status review undertaken by discretion of the Service. Results of the review may be to propose listing, make a species a candidate for listing, provide notice of a not warranted candidate assessment, or other action as appropriate. Proposed Listing Determination: For species that are already candidates for listing, a proposed listing determination would either propose the species for listing or provide notice of a not warranted finding. We generally intend to propose critical habitat designations concurrent with proposed listing rules, to the extent prudent and determinable. Final Listing Determination: For species that have already been proposed for listing, the final listing determination would either finalize or withdraw the proposed listing rule. We generally intend to finalize critical habitat designations concurrent with final listing rules, to the extent prudent and determinable. PCH: Proposed critical habitat rulemaking when not concurrent with a proposed listing rule. FCH: Final critical habitat rulemaking for previously proposed critical habitat. rPCH: Revised proposed critical habitat for previously proposed, but not finalized, critical habitat needing revision. Priority -

An Inventory of a Subset of Historically Known Populations of The

Section 6 (Texas Traditional) Report Review Form emailed to FWS S6 coordinator (mm/dd/yyyy): 9/11/2017 TPWD signature date on report: 8/31/2017 Project Title: To provide more evidence for the presence/absence of the southern spot-tailed earless lizard (Holbrookia lacerata subcaudalis; STEL) in southern Texas. Final or Interim Report? Final Grant #: TX-E-165-R Reviewer Station: Austin ESFO Lead station concurs with the following comments: NA (reviewer from lead station) Interim Report (check one): Final Report (check one): Acceptable (no comments) Acceptable (no comments) Needs revision prior to final report (see Needs revision (see comments below) comments below) Incomplete (see comments below) Incomplete (see comments below) Comments: FINAL PERFORMANCE REPORT As Required by THE ENDANGERED SPECIES PROGRAM TEXAS Grant No. TX E-165-R (F14AP00824) Endangered and Threatened Species Conservation An Inventory of a Subset of Historically Known Populations of the Spot-tailed Earless Lizard (Holbrookia lacerata) Prepared by: Mike Duran Carter Smith Executive Director Clayton Wolf Director, Wildlife 31 August 2017 Final Report TPWD Contract #458178—31 August 2017 FINAL REPORT STATE: ____Texas_______________ GRANT NUMBER: ___ TX E-165-R-1__ GRANT TITLE: An Inventory of a Subset of Historically Known Populations of the Spot-tailed Earless Lizard (Holbrookia lacerata). REPORTING PERIOD: ____1 September 2014 to 31 August 2017 OBJECTIVE(S). To provide more evidence for the presence/absence of the southern spot-tailed earless lizard (Holbrookia lacerata subcaudalis; STEL) in southern Texas. Segment Objectives: Task 1. March 1 – June 30, 2015 – Spring surveys. Task 2. September 15 – October 31, 2015 – Fall surveys. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

4 References

4 References Agricultural Extension Office. 2000. Sedges. Available at: http://aquaplant.tamu.edu/Emergent%20Plants/Sedges/Sedges.htm Accessed April 2004 Allen, D.B., B.J. Flatter, J. Nelson and C. Medrow. 1998. Redband Trout Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri Population and Stream Habitat Surveys in Northern Owyhee County and the Owyhee River and Its Tributaries. 1997. Idaho BLM Technical Bulletin No. 98-14. American Fisheries Society, Idaho Chapter (AFS). 2000. Fishes of Idaho. Available at < http://www.fisheries.org/idaho/fishes_of_idaho.htm>. Accessed November 2003. American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU). 1957. Check-list of North American Birds. 5th edition. American Ornithological Union, Washington, DC. Anderson, A. E., and O. C. Wallmo. 1984. Odocoileus hemionus. Mammalian Species 219:1– 9. Anderson, J. L., K. Bacon, and K. Denny. 2002. Salmon River Habitat Enhancement. Annual Report 2001. Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, Fort Hall, ID. 14 pp. Anderson, M., P. Bourgeron, M. T. Bryer, R. Crawford, L. Engelking, D. Faber-Langendoen, M. Gallyoun, K. Goodin, D. H. Grossman, S. Landaal, K. Metzler, K. D. Patterson, M. Pyne, M. Reid, L. Sneddon, and A. S. Weakley. 1998. International Classification of Ecological Communities: Terrestrial Vegetation of the United States. Volume II. The National Vegetation Classification System: List of Types. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, VA. Arno, S. F. 1979. Forest Regions of Montana. Research Paper INT-218. U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. Arno, S.F. 1980. Forest Fire History in the Northern Rockies. Journal of Forestry 78:460–464. Aubry, K. B., Koehler, G. M., and J. R. Squires. -

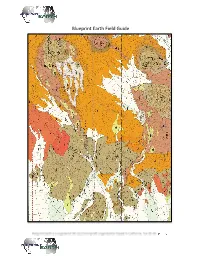

Blueprint Earth Field Guide

Blueprint Earth Field Guide Plants Note that this list is not comprehensive. If you are uncertain of the identification you’ve made of a particular plant, take a picture and a voucher (when possible) and discuss your observations with the Supervisory Scientist team. Trees & Bushes Joshua tree - Yucca brevifolia Parry saltbush - Atriplex parryi Mojave sage - Salvia pachyphylla Creosote bush - Larrea tridentata Mojave yucca - Yucca schidigera Chaparral yucca - Yucca whipplei Torr. Desert holly - A. hymenelytra Torr. Manzanita - Arctostaphylos Adans. Cacti Barrel cactus - Ferocactus cylindraceus var. Jumping cholla - Cylindropuntia bigelovii Engelm. lecontei Foxtail cactus - Escobaria vivipara var. alversonii Silver cholla - Opuntia echinocarpa var. echinocarpa Pencil cholla - Opuntia ramosissima Cottontop cactus - Echinocactus polycephalus Hedgehog cactus - Echinocereus engelmanii var. Mojave mound cactus - Echinocereeus chrysocentrus triglochiderus var. mojavensis Beavertail cactus - Opuntia basilaris Grasses Indian Rice Grass - Oryzopsis hymenoides Bush Muhly - Muhlenbergia porteri Fluff Grass - Erioneuron pulchella Red Brome - Bromus rubens Desert Needle - Stipa speciosa Big Galleta – Hilaria rigida Flowers Wooly Amsonia Chuparosa Amsonia tomentosa Justicia californica Brittlebush Encelia farinosa Chia Salvia columbariae Sacred Datura Desert Calico Datura wrightii Loeseliastrum matthewsii Bigelow Coreopsis Desert five-spot Coreopsis bigelovii Eremalche rotundifolia - Desert Chicory Rafinesquia Desert Lupine neomexicana Desert Larkspur -

News Release Albuquerque, NM 87103 505/248-6911 505/248-6915 (Fax)

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Public Affairs Office PO Box 1306 News Release Albuquerque, NM 87103 505/248-6911 505/248-6915 (Fax) Southwest Region (Arizona ● New Mexico ● Oklahoma ●Texas) www.fws.gov/southwest/ For Release: May 23, 2011 Contacts: Alisa Shull, (512) 490-0057 Lesli Gray, (972) 569-8588 THE SPOT-TAILED EARLESS LIZARD MAY WARRANT PROTECTION UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT The spot-tailed earless lizard (Holbrookia lacerata) may warrant federal protection as a threatened or endangered species, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) announced today, following an initial review of a petition seeking to protect the spot-tailed earless lizard under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The Service finds that the petition presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that listing the spot-tailed earless lizard may be warranted. This finding is based on potential threats posed by predation from fire ants. Fire ants are known to adversely impact native fauna in general, including reptiles. Fire ants occur across a large part of the spot-tailed earless lizard’s range and may pose a threat through direct predation on adults, hatchlings and eggs. The spot-tailed earless lizard is divided into two distinct subspecies, based on morphological (physical) differences and geographic separation. The northern spot-tailed earless lizard subspecies (Holbrookia lacerata lacerata) historically occurred throughout the Edwards Plateau in Texas. The southern spot-tailed earless lizard (Holbrookia lacerata subcaudalis) historically occurred through south Texas into parts of Mexico’s States of Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas. The present population of the spot-tailed earless lizard’s population status is largely unknown. -

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List Associated Tables The Texas Priority Species List……………..733 Introduction For many years the management and conservation of wildlife species has focused on the individual animal or population of interest. Many times, directing research and conservation plans toward individual species also benefits incidental species; sometimes entire ecosystems. Unfortunately, there are times when highly focused research and conservation of particular species can also harm peripheral species and their habitats. Management that is focused on entire habitats or communities would decrease the possibility of harming those incidental species or their habitats. A holistic management approach would potentially allow species within a community to take care of themselves (Savory 1988); however, the study of particular species of concern is still necessary due to the smaller scale at which individuals are studied. Until we understand all of the parts that make up the whole can we then focus more on the habitat management approach to conservation. Species Conservation In terms of species diversity, Texas is considered the second most diverse state in the Union. Texas has the highest number of bird and reptile taxon and is second in number of plants and mammals in the United States (NatureServe 2002). There have been over 600 species of bird that have been identified within the borders of Texas and 184 known species of mammal, including marine species that inhabit Texas’ coastal waters (Schmidly 2004). It is estimated that approximately 29,000 species of insect in Texas take up residence in every conceivable habitat, including rocky outcroppings, pitcher plant bogs, and on individual species of plants (Riley in publication). -

Ecosystem Disturbance and Wildlife Conservation in Western Grasslands

Evolution and management of the North American grassland herpetofauna Norman J. Scott, Jr.1 Abstract.—The modern North American grassland herpetofauna has evolved in situ since the Miocene. Pleistocene glaciation had a minimal effect except in the far North, with only minor displacements of some species. South of the glaciers, winters were warmer and summers cooler than at present. Snake- like reptiles, leaping frogs, and turtle “tanks” are favored adaptive types in uniform dense grassland. A typical fauna consists of about 10-15 species, mostly snakes. Special habitat components, such as streams and ponds, bare ground, sand, trees, prairie dog towns, and rocky outcrops, add distinct suites of species. There is also an increase in species number from north to south and west to east. Grassland use and management, such as prairie dog con- trol, off-road vehicle traffic, and brush removal, have demonstrable effects on the herpetofauna. However, the effects of three of the most widespread management procedures—water development, grazing, and fire—are largely unstudied. Although highly fragmented, the majority of species of grassland reptiles and amphibians are widespread and populations are resilient, but there are special conservation problems associated with Pleistocene relicts with limited distributions. INTRODUCTION Parmenter et al. (1994) documented the excep- tionally high vertebrate diversity in southwestern At the time of the arrival of Europeans in North rangelands, and they emphasized that preserva- America, much of the interior of the continent was tion of this biodiversity in the remaining habitat covered by grasslands. The heart of this great fragments will depend on skillful management of expanse was the tallgrass prairie of the human activities in a fashion that integrates faunal midwestern United States. -

Sprint Performance of Phrynosomatid Lizards, Measured on a High-Speed Treadmill, Correlates with Hindlimb Length

J. Zool., Lond. (1999) 248, 255±265 # 1999 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom Sprint performance of phrynosomatid lizards, measured on a high-speed treadmill, correlates with hindlimb length Kevin E. Bonine and Theodore Garland, Jr Department of Zoology, University of Wisconsin, 430 Lincoln Drive, Madison, WI 53706-1381, U.S.A. (Accepted 19 September 1998) Abstract We measured sprint performance of phrynosomatid lizards and selected outgroups (n = 27 species). Maximal sprint running speeds were obtained with a new measurement technique, a high-speed treadmill (H.S.T.). Animals were measured at their approximate ®eld-active body temperatures once on both of 2 consecutive days. Within species, individual variation in speed measurements was consistent between trial days and repeatabilities were similar to values reported previously for photocell-timed racetrack measure- ments. Multiple regression with phylogenetically independent contrasts indicates that interspeci®c variation in maximal speed is positively correlated with hindlimb span, but not signi®cantly related to either body mass or body temperature. Among the three phrynosomatid subclades, sand lizards (Uma, Callisaurus, Cophosaurus, Holbrookia) have the highest sprint speeds and longest hindlimbs, horned lizards (Phryno- soma) exhibit the lowest speeds and shortest limbs, and the Sceloporus group (including Uta and Urosaurus) is intermediate in both speed and hindlimb span. Key words: comparative method, lizard, locomotion, morphometrics, phrynosomatidae, sprint speed INTRODUCTION Fig. 1; Montanucci, 1987; de Queiroz, 1992; Wiens & Reeder, 1997) that exhibit large variation in locomotor Evolutionary physiologists and functional morpholo- morphology and performance, behaviour, and ecology gists emphasize the importance of direct measurements (Stebbins, 1985; Conant & Collins, 1991; Garland, 1994; of whole-animal performance (Arnold, 1983; Garland & Miles, 1994a). -

Amphibians, Reptiles and Mammals … a Species Checklist for the Gila

Using the Checklist Vegetation types on the Gila National Forest range from spruce/fir on the Fish, Mogollon Mountains and the Black Range, to Desert Scrub and remnant Grassland at lower elevations in the Burro Mountains. Ponderosa pine is the Amphibians, dominant species at mid-elevations, 6,000 to 7,000 feet. Piñon/Juniper or oak/juniper/piñon woodland is found on drier sites throughout the forest. This Reptiles and extreme range in elevation and the many corresponding vegetation types provide for a diverse fauna which includes 30 fish species, 11 amphibians, 44 reptiles and 84 mammals. Resident status is given only for migratory bats (see Mammals … below). The remaining categories describe the habitat(s) where one is most A Species Checklist for The Gila National Forest likely to encounter each species, and specific habitat requirements. Checklist Key C – Common U – Uncommon F – Fairly Common X -- Extirpated R – Rare Vegetation Type Preference 1. Desert 6. Spruce-Fir 2. Oak Woodland 7. Mt. Grassland 3. Oak-Juniper 8. Marsh/Open 4. Piñon-Juniper 9. Decid. Riparian 5. Ponderosa Pine 10. Conif. Riparian Residency The Residence column is for bats only and lists the time of year each Species normally appears in the checklist area. P – Permanent Resident S – Summer Resident W – Winter Resident Federal Status The particular status of species that are “listed” is shown in parenthesis PREPARED BY following the name. United States Forest Service Southwestern Department of Region E-Endangered T-Threatened S- Sensitive *R-Reintroduced Agriculture Illustrations by Hank Pavlokovich PRODUCED IN COOPERATION WITH Southwestern New Mexico Audubon Society *The Mexican Gray Wolf was reintroduced to the area in 1998.