The Crosstalk Between Hifs and Mitochondrial Dysfunctions in Cancer Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplement 1 Overview of Dystonia Genes

Supplement 1 Overview of genes that may cause dystonia in children and adolescents Gene (OMIM) Disease name/phenotype Mode of inheritance 1: (Formerly called) Primary dystonias (DYTs): TOR1A (605204) DYT1: Early-onset generalized AD primary torsion dystonia (PTD) TUBB4A (602662) DYT4: Whispering dystonia AD GCH1 (600225) DYT5: GTP-cyclohydrolase 1 AD deficiency THAP1 (609520) DYT6: Adolescent onset torsion AD dystonia, mixed type PNKD/MR1 (609023) DYT8: Paroxysmal non- AD kinesigenic dyskinesia SLC2A1 (138140) DYT9/18: Paroxysmal choreoathetosis with episodic AD ataxia and spasticity/GLUT1 deficiency syndrome-1 PRRT2 (614386) DYT10: Paroxysmal kinesigenic AD dyskinesia SGCE (604149) DYT11: Myoclonus-dystonia AD ATP1A3 (182350) DYT12: Rapid-onset dystonia AD parkinsonism PRKRA (603424) DYT16: Young-onset dystonia AR parkinsonism ANO3 (610110) DYT24: Primary focal dystonia AD GNAL (139312) DYT25: Primary torsion dystonia AD 2: Inborn errors of metabolism: GCDH (608801) Glutaric aciduria type 1 AR PCCA (232000) Propionic aciduria AR PCCB (232050) Propionic aciduria AR MUT (609058) Methylmalonic aciduria AR MMAA (607481) Cobalamin A deficiency AR MMAB (607568) Cobalamin B deficiency AR MMACHC (609831) Cobalamin C deficiency AR C2orf25 (611935) Cobalamin D deficiency AR MTRR (602568) Cobalamin E deficiency AR LMBRD1 (612625) Cobalamin F deficiency AR MTR (156570) Cobalamin G deficiency AR CBS (613381) Homocysteinuria AR PCBD (126090) Hyperphelaninemia variant D AR TH (191290) Tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency AR SPR (182125) Sepiaterine reductase -

Assessment of a Targeted Gene Panel for Identification of Genes Associated with Movement Disorders

Supplementary Online Content Montaut S, Tranchant C, Drouot N, et al; French Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Consortium. Assessment of a targeted gene panel for identification of genes associated with movement disorders. JAMA Neurol. Published online June 18, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1478 eMethods. Supplemental methods. eTable 1. Name, phenotype and inheritance of the genes included in the panel. eTable 2. Probable pathogenic variants identified in a cohort of 23 patients with cerebellar ataxia using WES analysis. eTable 3. Negative cases in a cohort of 23 patients with cerebellar ataxia studied using WES analysis. eTable 4. Variants of unknown significance (VUSs) identified in the cohort. eFigure 1. Examples of pedigrees of cases with identified causative variants. eFigure 2. Pedigrees suggesting mendelian inheritance in negative cases. eFigure 3. Examples of pedigrees of cases with identified VUSs. eResults. Supplemental results. This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/26/2021 eMethods. Supplemental methods Patients selection In the multicentric, prospective study, patients were selected from 25 French, 1 Luxembourg and 1 Algerian tertiary MDs centers between September 2014 and July 2016. Inclusion criteria were patients (1) who had developed one or several chronic MDs (2) with an age of onset below 40 years and/or presence of a family history of MDs. Patients suffering from essential tremor, tic or Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, pure cerebellar ataxia or with clinical/paraclinical findings suggestive of an acquired cause were excluded. -

1 Metabolic Dysfunction Is Restricted to the Sciatic Nerve in Experimental

Page 1 of 255 Diabetes Metabolic dysfunction is restricted to the sciatic nerve in experimental diabetic neuropathy Oliver J. Freeman1,2, Richard D. Unwin2,3, Andrew W. Dowsey2,3, Paul Begley2,3, Sumia Ali1, Katherine A. Hollywood2,3, Nitin Rustogi2,3, Rasmus S. Petersen1, Warwick B. Dunn2,3†, Garth J.S. Cooper2,3,4,5* & Natalie J. Gardiner1* 1 Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 2 Centre for Advanced Discovery and Experimental Therapeutics (CADET), Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre, Manchester, UK 3 Centre for Endocrinology and Diabetes, Institute of Human Development, Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 4 School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, New Zealand 5 Department of Pharmacology, Medical Sciences Division, University of Oxford, UK † Present address: School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, UK *Joint corresponding authors: Natalie J. Gardiner and Garth J.S. Cooper Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Address: University of Manchester, AV Hill Building, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PT, United Kingdom Telephone: +44 161 275 5768; +44 161 701 0240 Word count: 4,490 Number of tables: 1, Number of figures: 6 Running title: Metabolic dysfunction in diabetic neuropathy 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online October 15, 2015 Diabetes Page 2 of 255 Abstract High glucose levels in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy (DN). However our understanding of the molecular mechanisms which cause the marked distal pathology is incomplete. Here we performed a comprehensive, system-wide analysis of the PNS of a rodent model of DN. -

Ubiquitination/Deubiquitination and Acetylation/Deacetylation

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2011) 32: 139–140 npg © 2011 CPS and SIMM All rights reserved 1671-4083/11 $32.00 www.nature.com/aps Research Highlight Ubiquitination/deubiquitination and acetylation/ deacetylation: Making DNMT1 stability more coordinated Qi HONG, Zhi-ming SHAO* Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2011) 32: 139–140; doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.3 n mammals, DNA methylation plays important role in human cancers[7, 8]. abundance of DNMT1 mutant lacking Ia crucial role in the regulation of Ubiquitinproteasome pathway is sig the HAUSP interaction domain, but not gene expression, telomere length, cell nificant in the stability of DNMT1[8], but the fulllength protein. These results differentiation, X chromosome inactiva ubiquitinmediated protein degradation show the coordination between ubiquit tion, genomic imprinting and tumori can be enhanced or attenuated by some ination of DNMT1 by UHRF1 and deu genesis[1]. DNA methylation patterns modifications like acetylation/deacety biquitination by HAUSP. Furthermore, are established de novo by DNA meth lation, protein methylation/demethyla they found that knockdown of HDAC1 yltransferases (DNMTs) 3a and 3b, tion, phosphorylation and Snitrosy increased DNMT1 acetylation, and whereas DNMT1 maintains the parent lation[9–11]. Estève et al demonstrated reduced DNMT1 abundance. Addition specific methylation from parental cells that SET7mediated lysine methy lation ally, acetyltransferase Tip60 which was to their progeny[2]. After DNA replica of DNMT1 decreased DNMT1 level found to acetylate DNMT1 promoted its tion, the new DNA strand is unmethy by ubiquitinmediated degradation[10]. ubiquitination, then destabilized it. At lated. Thus with the mother methylated Furthermore, an early study[12] showed last, Tip60 and HAUSP were found to strand, the DNA is hemimethylated. -

1 AGING Supplementary Table 2

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES Supplementary Table 1. Details of the eight domain chains of KIAA0101. Serial IDENTITY MAX IN COMP- INTERFACE ID POSITION RESOLUTION EXPERIMENT TYPE number START STOP SCORE IDENTITY LEX WITH CAVITY A 4D2G_D 52 - 69 52 69 100 100 2.65 Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ B 4D2G_E 52 - 69 52 69 100 100 2.65 Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ C 6EHT_D 52 - 71 52 71 100 100 3.2Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ D 6EHT_E 52 - 71 52 71 100 100 3.2Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ E 6GWS_D 41-72 41 72 100 100 3.2Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ F 6GWS_E 41-72 41 72 100 100 2.9Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ G 6GWS_F 41-72 41 72 100 100 2.9Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ H 6IIW_B 2-11 2 11 100 100 1.699Å UHRF1 X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ www.aging-us.com 1 AGING Supplementary Table 2. Significantly enriched gene ontology (GO) annotations (cellular components) of KIAA0101 in lung adenocarcinoma (LinkedOmics). Leading Description FDR Leading Edge Gene EdgeNum RAD51, SPC25, CCNB1, BIRC5, NCAPG, ZWINT, MAD2L1, SKA3, NUF2, BUB1B, CENPA, SKA1, AURKB, NEK2, CENPW, HJURP, NDC80, CDCA5, NCAPH, BUB1, ZWILCH, CENPK, KIF2C, AURKA, CENPN, TOP2A, CENPM, PLK1, ERCC6L, CDT1, CHEK1, SPAG5, CENPH, condensed 66 0 SPC24, NUP37, BLM, CENPE, BUB3, CDK2, FANCD2, CENPO, CENPF, BRCA1, DSN1, chromosome MKI67, NCAPG2, H2AFX, HMGB2, SUV39H1, CBX3, TUBG1, KNTC1, PPP1CC, SMC2, BANF1, NCAPD2, SKA2, NUP107, BRCA2, NUP85, ITGB3BP, SYCE2, TOPBP1, DMC1, SMC4, INCENP. RAD51, OIP5, CDK1, SPC25, CCNB1, BIRC5, NCAPG, ZWINT, MAD2L1, SKA3, NUF2, BUB1B, CENPA, SKA1, AURKB, NEK2, ESCO2, CENPW, HJURP, TTK, NDC80, CDCA5, BUB1, ZWILCH, CENPK, KIF2C, AURKA, DSCC1, CENPN, CDCA8, CENPM, PLK1, MCM6, ERCC6L, CDT1, HELLS, CHEK1, SPAG5, CENPH, PCNA, SPC24, CENPI, NUP37, FEN1, chromosomal 94 0 CENPL, BLM, KIF18A, CENPE, MCM4, BUB3, SUV39H2, MCM2, CDK2, PIF1, DNA2, region CENPO, CENPF, CHEK2, DSN1, H2AFX, MCM7, SUV39H1, MTBP, CBX3, RECQL4, KNTC1, PPP1CC, CENPP, CENPQ, PTGES3, NCAPD2, DYNLL1, SKA2, HAT1, NUP107, MCM5, MCM3, MSH2, BRCA2, NUP85, SSB, ITGB3BP, DMC1, INCENP, THOC3, XPO1, APEX1, XRCC5, KIF22, DCLRE1A, SEH1L, XRCC3, NSMCE2, RAD21. -

Supplemental Table 10

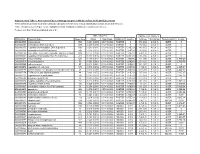

Supplemental Table 10: Dietary Impact on the Heart Sulfhydrome DR/AL Accession Alternate Molecular Cysteine Spectral Protein Name Number ID Weight Residues Count Ratio P‐value Ig lambda‐2 chain C region P01844 Iglc2 11 kDa 3 C 16.000 0.00101 Gelsolin P13020 (+1) Gsn 86 kDa 7 C 11.130 0.00133 Glutamate‐‐cysteine ligase regulatory subunit O09172 Gclm 31 kDa 6 C 10.200 0.0307 Ig gamma‐3 chain C region P03987 44 kDa 10 C 7.636 0.0005 Ferritin heavy chain P09528 Fth1 21 kDa 3 C 6.182 0.02617 Antithrombin‐III P32261 Serpinc1 52 kDa 9 C 5.333 0.03116 Bisphosphoglycerate mutase P15327 Bpgm 30 kDa 3 C 4.645 0.01998 Vitamin D‐binding protein Q9QVP4 Gc 54 kDa 28 C 4.541 0.0206 Properdin P11680 Cfp 50 kDa 44 C 3.692 0.0227 Complement factor B P01867 (+1) Cfb 85 kDa 20 C 3.636 0.01126 Transforming growth factor beta‐1 P04202 Tgfb1 44 kDa 12 C 3.273 0.00601 Ferritin light chain 1 P29391 Ftl1 21 kDa 1 C 3.250 0.0204 Ig lambda‐1 chain C region Q9CPV4‐2 12 kDa 3 C 2.844 0.02618 Kininogen‐1 Q8K182 Kng1 73 kDa 19 C 2.840 0.01359 Beta‐2‐glycoprotein 1 Q01339 Apoh 39 kDa 23 C 2.691 0.00579 Complement C3 P01027 C3 186 kDa 27 C 2.556 0.00991 Complement factor I P02088 Cfi 67 kDa 40 C 2.324 0.02636 Ig heavy chain V region 102 P01750 13 kDa 3 C 16.200 0.1642 Afamin O89020 (+1) Afm 69 kDa 34 C 14.400 0.07963 Dehydrogenase/reductase SDR family member 11 Q3U0B3 Dhrs11 28 kDa 8 C 10.400 0.09207 Myosin light chain 4 P09541 Myl4 21 kDa 2 C 9.908 0.23919 Myeloperoxidase P11247 Mpo 81 kDa 16 C 8.800 0.40708 Myosin regulatory light chain 2, skeletal muscle isoform P97457 -

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Growth and Gene Expression Profile Analyses of Endometrial Cancer Cells Expressing Exogenous PTEN

[CANCER RESEARCH 61, 3741–3749, May 1, 2001] Growth and Gene Expression Profile Analyses of Endometrial Cancer Cells Expressing Exogenous PTEN Mieko Matsushima-Nishiu, Motoko Unoki, Kenji Ono, Tatsuhiko Tsunoda, Takeo Minaguchi, Hiroyuki Kuramoto, Masato Nishida, Toyomi Satoh, Toshihiro Tanaka, and Yusuke Nakamura1 Laboratories of Molecular Medicine [M. M-N., M. U., K. O., T. M., T. Ta., Y. N.] and Genome Database [T. Ts.], Human Genome Center, Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 108-8639, Japan; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Kitasato University, Sagamihara 228-8555, Japan [H. K.]; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba 305-8576, Japan [M. N.]; and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ibaraki Seinan Central Hospital, Tsukuba 306-0433, Japan [T. S.] ABSTRACT Akt/protein kinase B, cell survival, and cell proliferation (8). Over- expression of PTEN can decrease cell proliferation and tumorigenicity The PTEN tumor suppressor gene encodes a multifunctional phospha- (9, 10), an observation attributed to the ability of PTEN to induce cell tase that plays an important role in inhibiting the phosphatidylinositol-3- cycle arrest and apoptosis (11, 12). kinase pathway and downstream functions that include activation of Akt/protein kinase B, cell survival, and cell proliferation. Enforced ex- Thus, lack of PTEN expression may affect a complex set of pression of PTEN in various cancer cell lines decreases cell proliferation transcriptional targets. However, no systematic assessment of PTEN- through arrest of the cell cycle, accompanied in some cases by induction regulated targets in cancer cells has been reported to date. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0082511 A1 Brown Et Al

US 20030082511A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0082511 A1 Brown et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 1, 2003 (54) IDENTIFICATION OF MODULATORY Publication Classification MOLECULES USING INDUCIBLE PROMOTERS (51) Int. Cl." ............................... C12O 1/00; C12O 1/68 (52) U.S. Cl. ..................................................... 435/4; 435/6 (76) Inventors: Steven J. Brown, San Diego, CA (US); Damien J. Dunnington, San Diego, CA (US); Imran Clark, San Diego, CA (57) ABSTRACT (US) Correspondence Address: Methods for identifying an ion channel modulator, a target David B. Waller & Associates membrane receptor modulator molecule, and other modula 5677 Oberlin Drive tory molecules are disclosed, as well as cells and vectors for Suit 214 use in those methods. A polynucleotide encoding target is San Diego, CA 92121 (US) provided in a cell under control of an inducible promoter, and candidate modulatory molecules are contacted with the (21) Appl. No.: 09/965,201 cell after induction of the promoter to ascertain whether a change in a measurable physiological parameter occurs as a (22) Filed: Sep. 25, 2001 result of the candidate modulatory molecule. Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 1 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 KCNC1 cDNA F.G. 1 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 2 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 49 - -9 G C EH H EH N t R M h so as se W M M MP N FIG.2 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 3 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 FG. 3 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 4 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 KCNC1 ITREXCHO KC 150 mM KC 2000000 so 100 mM induced Uninduced Steady state O 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 Time (seconds) FIG. -

UHRF1 Depletion Suppresses Growth of Gallbladder Cancer Cells Through Induction of Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest

ONCOLOGY REPORTS 31: 2635-2643, 2014 UHRF1 depletion suppresses growth of gallbladder cancer cells through induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest YIYU QIN1, JIANDONG WANG1, WEI GONG1, MINGDI ZHANG1, ZHAOHUI TANG1, JUN ZHANG2 and ZHIWEI QUAN1 1Department of General Surgery and 2Ministry of Education-Shanghai Key Laboratory of Children's Environmental Health, Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200092, P.R. China Received December 28, 2013; Accepted February 21, 2014 DOI: 10.3892/or.2014.3145 Abstract. Ubiquitin-like containing PHD and RING finger proliferation and migration of GBC cells and may serve as a domains 1 (UHRF1), overexpressed in various human biomarker or even a therapeutic target for GBC. malignancies, functions as an important regulator in cell proliferation and epigenetic regulation. Depletion of UHRF1 Introduction has shown potential antitumor activities in several types of cancer. However, the role of UHRF1 in gallbladder cancer Gallbladder cancer (GBC) represents the most frequent and (GBC) has not been investigated. RT-PCR, western blotting aggressive type among biliary tract malignancies. Although and immunohistochemistry were performed to examine recent advances have been made in the diagnosis and treatment, UHRF1 expression at mRNA and protein levels in GBC tissues GBC has a poor overall prognosis with a 5-year survival rate and cell lines. UHRF1 siRNA and UHRF1 shRNA were used <10% (1). Currently, radical resection remains the mainstay of to deplete the expression of UHRF1. The results showed treatment for GBC. However, due to lacking typical symptoms that UHRF1 was overexpressed in GBC and its expression and specific biomarkers, most GBC patients are diagnosed correlated with advanced TNM stage and presence of lymph at advanced stages with unresectable tumors. -

Uhrf1-Mediated Tnf-Α Gene Methylation Controls

Uhrf1-Mediated Tnf-α Gene Methylation Controls Proinflammatory Macrophages in Experimental Colitis Resembling Inflammatory Bowel Disease This information is current as of September 30, 2021. Shanshan Qi, Yongkui Li, Zheng Dai, Mengxi Xiang, Guobin Wang, Lin Wang and Zheng Wang J Immunol published online 14 October 2019 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2019/10/12/jimmun ol.1900467 Downloaded from Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2019/10/12/jimmunol.190046 Material 7.DCSupplemental http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication by guest on September 30, 2021 *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2019 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Published October 14, 2019, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1900467 The Journal of Immunology Uhrf1-Mediated Tnf-a Gene Methylation Controls Proinflammatory Macrophages in Experimental Colitis Resembling Inflammatory Bowel Disease Shanshan Qi,*,1 Yongkui Li,*,1 Zheng Dai,* Mengxi Xiang,* Guobin Wang,*,† Lin Wang,*,‡ and Zheng Wang*,† Macrophages drive the pathological process of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) mostly by secreting proinflammatory cytokines, such as Tnf-a.