1 Acts 22:22-23:11 No. 47

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I= I Am Jesus Important Woman Raised from the Dead Acts 9

I= I am Jesus Important Woman Raised from the Dead Acts 9 Saul/Paul’s conversion is the most famous conversion in history. Paul was born a Jew born in Tarsus. Under Gamaliel (chapter 5) he was taught the law. Remember back to Acts 7 & 8; he was at Stephen’s stoning, and he was dragging people off to prison. Now we meet him in Acts 9 with orders to arrest people. He was on the road to Damascus. Damascus was 140 miles from Jersualem. It was a one week journey. The “Way” in verse 2 is the church. Paul’s conversion story is also in Acts 22 and 26. Around noon when a bright light flashed around Paul, he fell to the ground. A voice said, “Saul, Saul do you persecute me?” Saul answered, “Who are you Lord?” Jesus replied, “I am Jesus whom you are persecuting” When Paul stood up, he was blind. For 3 days, he didn’t eat or drink. What did he do then? VS 11 says Paul was praying. The Lord appeared to Ananias in a vision and told him to go find Paul. Paul would be waiting on Ananias to restore his sight. Ananias didn’t want to go at first. He had heard stories about Paul. The Lord insisted and told Ananias that Paul was the chosen instrument for the Gentiles. Ananias went and laid his hands on Saul and told him to receive his sight. Then Ananias told him (Acts 22:14,15) God has appointed you to know his will and be a witness to all men of what you have seen and heard. -

Michigan Bible School “The

MICHIGAN BIBLE SCHOOL August – December 2005 Revised November 2008 “THE BOOK OF ACTS” Instructor: Charles Coats 4514 Grand River East Webberville, MI 48892 E-Mail: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview ……………………………………………………………............. 3 Acts 1 & 2 ……………………………………………………………………. 6 Acts 3-5 ……………………………………………………………………. 10 Acts 6,7 ……………………………………………………………………. 14 Acts 8,9 ……………………………………………………………………. 18 Acts 10-12 ……………………………………………………………………. 24 Acts 13:1 – 15:35 ……………………………………………………………. 28 Acts 15:36 – 18:22 ……………………………………………………………. 32 Acts 18:23 – 21:30 ……………………………………………………………. 36 Acts 21:31 – 26:32 …………………………………………………………….. 40 Acts 27:1 – 28:31 …………………………………………………………….. 43 Book of Acts Chapter by Chapter ……………………………………………. 45 Growth of the church …………………………………………………….. 46 Salvation ……………………………………………………………………... 49 They turned the world upside down ………………………………………………55 The “problem” of handmaids and concubines ………………………………58 2 I. AN OVERVIEW OF THE BOOK OF ACTS a. This book begins with the ascension of Jesus and his instructions for the apostles to go into Jerusalem and to wait from the power on high (Acts 1:4,5). b. It continues by showing us the establishment of the church and the subsequent spread of the church (From Acts 2 on). c. The book gives us the early persecution against the church and depicts for us the boldness of the early church (cf. Acts 4:29). d. We find in this book the first Gentile to be converted and the taking of the gospel into Asia Minor and Europe, as well as some of the islands of the Mediterranean. e. Acts 2 is sometimes referred to as the “hub of the Bible”. Everything prior to Acts 2 points to the coming establishment of the church. Everything after Acts 2 points back to the establishment of the church. -

FROM PENTECOST to PRISON Or the Acts of the Apostles

FROM PENTECOST TO PRISON or The Acts of the Apostles Charles H. Welch 2 FROM PENTECOST TO PRISON or The Acts of the Apostles by Charles H. Welch Author of Dispensational Truth The Apostle of the Reconciliation The Testimony of the Lord's Prisoner Parable, Miracle, and Sign The Form of Sound Words Just and the Justifier In Heavenly Places etc. THE BEREAN PUBLISHING TRUST 52A WILSON STREET LONDON EC2A 2ER First published as a series of 59 articles in The Berean Expositor Vols. 24 to 33 (1934 to 1945) Published as a book 1956 Reset and reprinted 1996 ISBN 0 85156 173 X Ó THE BEREAN PUBLISHING TRUST 3 Received Text (Textus Receptus) This is the Greek New Testament from which the Authorized Version of the Bible was prepared. Comments in this work on The Acts of the Apostles are made with this version in mind. CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 THE BOOK AS A WHOLE............................................................... 6 2 THE FORMER TREATISE The Gentile in the Gospel of Luke ........................................ 8 3 LUKE 24 AND ACTS 1:1-14........................................................ 12 4 RESTORATION The Lord’s own teaching concerning the restoration of the kingdom to Israel .......................................................... 16 The question of Acts 1:6. Was it right?............................... 19 The O.T. teaching concerning the restoration of the kingdom to Israel .......................................................... 19 5 THE HOPE OF THE ACTS AND EPISTLES OF THE PERIOD................ 20 Further teaching concerning the hope of Israel in Acts 1:6-14............................................................... 22 6 THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE ACTS AND ITS WITNESS Jerusalem - Antioch - Rome................................................ 26 7 RESTORATION, RECONCILIATION, REJECTION The three R’s..................................................................... -

Living in the Promises of Jesus Acts 21-22 Lesson 15

Living in the Promises of Jesus Acts 21-22 Lesson 15 OBSERVATION: Read Acts 21, 22 1. After reading through these verses, what would you say to someone if they asked you what they are about? 2. Key words help us to better understand the verses. We have listed below a group of key words. Mark each one in a distinctive way Key Words: God, Jesus, Holy Spirit, and Paul. Acts 22: Key Words: God, Jesus, and Paul PAUL'S READINESS TO DIE: Read Acts 21:1-14 1. We left chapter 20 with Paul (in Miletus) bidding farewell to the elders of the church in Ephesus. Using Acts 21:1-3, trace Paul's journey to Tyre. 2. Paul and his companions stayed in Tyre for seven days. What did the disciples in Tyre tell Paul? Verse 4 a. What do we learn about Paul’s ministry from Acts 20:23? b. Given the stated concern for Paul's safety in Jerusalem and knowing they would not see Paul again, describe what this scene must have been like. 1 3. Who did Paul's companions stay with in Caesarea? 4. What do we know about Philip from: Acts 6:5 Acts 8:5-40 Acts 21:8 Acts 21:9 4. Notice, Philip's daughters prophesied. However, we are not told that they prophesied regarding Paul's impending trip to Jerusalem. What two things does this teach us about this gift of prophecy? 5. Rather than prophesy through Philip's daughters, the Holy Spirit chose to use a man named Agabus. -

Sharing Your Testimony [email protected]

Tuesday, 10 March 2015 Capitol Commission Georgia Ron J. Bigalke, Ph.D. P.O. Box 244, Rincon, GA 31326-0244 (912) 659-4212 Sharing Your Testimony [email protected] WHY SHARE YOUR TESTIMONY 1) Love for God and a Desire to Bring Him Glory CAPITOL BIBLE STUDY • God is glorified when his people give witness to his character and conduct; • God is glorified when his commandments are heeded; rd 153 General Assembly • God is glorified when others share his grace; • God’s enemy, Satan, is defeated. • TUESDAY @ 7:30 AM in 403 CAP 2) Love for People and a Concern for Their Future • A desire to guide a lost person from darkness to light, and from • TUESDAY @ 12 NOON in 123 CAP hopelessness to hope. THE VALUE OF YOUR TESTIMONY Capitol Commission Bible Studies are held Tuesday mornings at Most people are interested in the personal stories of others. To be 7:30am and again at 12 Noon. The weekly Bible study is nonpartisan effective in relating the story of your faith in Christ, it must be and non-denominational. The remaining studies for the 2015 interesting, well-developed and personal. Just as it is natural and General Assembly will be in the book of Romans. enjoyable to retell personal occurrences such as special occasions, I pray that this study will be edifying to you. I am here to serve unusual adventures, and life-changing experiences, it should be you and to be a resource for prayer and counsel. Please accept my natural and enjoyable to share your personal testimony. -

Paul's Conversion and Luke's Portrayal of Character In

Tyndale Bulletin 54.2 (2003) 63-80. PAUL’S CONVERSION AND LUKE’S PORTRAYAL OF CHARACTER IN ACTS 8–10 Philip H. Kern Summary Luke’s portrait of Saul shows him to lack a right relationship with God. This is accomplished in part by contrasting the pre-conversion Saul with Stephen, the Ethiopian eunuch, and Cornelius. After his experience on the Damascus road, Paul is portrayed in ways that resemble Stephen and Peter, while Bar Jesus and the Philippian gaoler, who clearly oppose God and Christianity, are portrayed in ways that recall the earlier portrait of Saul and inform how we are to understand him pre-conversion. Thus Luke connects opposition to the church with opposition to God, and shows that Saul, in opposing the former, was an enemy of the latter. By showing the change from an enemy to one who himself suffers for the gospel, Luke indicates that Paul has entered into a relationship with God. This suggests, furthermore, that Paul joined an already established movement. I. Introduction The debate that began in 1963 with Krister Stendahl’s suggestion that Paul was not converted, that the Damascus Road experience was a call to ministry, and that Paul’s conscience was sufficiently ‘robust’ to exclude the need for conversion to a new religion, continues unabated.1 Often those who deny that Paul was converted insist on the impossibility of moving from Judaism to Christianity since the latter did not yet exist.2 1 See esp. K. Stendahl, Paul Among Jews and Gentiles—And Other Essays (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1976), 7–23. -

Lesson 401: Acts 22:1-30

a Grace Notes course The Acts of the Apostles an expositional study by Warren Doud Lesson 401: Acts 22:1-30 Grace Notes 1705 Aggie Lane, Austin, Texas 78757 Email: [email protected] ACTS ACTS401 - Acts 22:1-30 Contents ACTS 22:1-30 .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Baptism ........................................................................................................................................................................ 10 Damascus ..................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Hellenists and Arameans ............................................................................................................................................. 16 Persecution of the Early Church .................................................................................................................................. 19 The Acts of the Apostles Page 3 ACTS 401, Acts 22:1-30 a Grace Notes study ACTS 22:1-30 ACTS 22:3. I am verily a man which am a Jew, By birth, a thorough genuine one; an ACTS 22:1. Men, brethren, and fathers, A Hebrew of the Hebrews, both by father and common form of address used by the Jews; mother side, both parents being Jews, and so a (see Acts 7:2) but that the apostle should true descendant from Abraham, Isaac, and introduce his speech to these people in this -

Sermon 7-29-2018 Acts 22:6-29 “Reformation: the Power of Identity”

Sermon 7-29-2018 Acts 22:6-29 “ReFormation: The Power of Identity” Bottom line: God can use every aspect of our lives to influence people and spread the Gospel. When we follow Jesus, we are not asked to deny our personalities, interests and ideas. God can use those to reach people in unique and powerful ways I. Introduction to the end of the series a. Formed and reformed in God’s spirit, working our way through Acts and seeing how God is constantly in the business of expanding our imagination and understanding of how the Spirit is at work i. We have seen how the spirit fell where it pleased at Pentecost, empowering those in Jerusalem to speak the gospel in all different tongues. We’ve heard how Peter saw that God was at work in the Gentiles as Cornelius helped him to interpret a dream that he had, realizing that God was much bigger than he had ever previously imagined. And we have heard about the conversion of Paul, a former persecutor of Christians, until he met Jesus on the road to Damascus and then began to spread the gospel all over the world. ii. That’s where our scripture finds us today. II. Paul’s story a. Specific time and place i. Pentecost, in Jerusalem. Paul is speaking in a synagogue and sharing his conversion story. The Jews that are listening and are in support of his message until he mentions the Gentiles. They are angry and take him outside to kill him. But then somewhat miraculously, he is taken into custody by the Roman army. -

Damascus: Ananias” Sermon Date: September 27/28

WEEK 1 WEEK 1 WEEK 1 WEEKWeek 3 WEEK 1 WEEK 1 WEEK 1 1 Week of September 21-27 Acts 9:1-22 “Damascus: Ananias” Sermon Date: September 27/28 Damascus, early 20th century, gate into Straight Street Saul was born in Tarsus, a city in the Roman province of Cilicia. His parents probably named him after Israel’s first king and gave him a strong religious upbringing. Luke uses Saul, the Hebrew form of Paul’s name, until Acts 13:9 where he writes, “Saul, who was also called Paul.” When in Jerusalem, the apostle is called by his Hebrew name; while on evangelistic missions in Gentile areas, he is called Paul, the Roman form of his name. Paul wrote 13 of the 27 New Testament books. Although he greatly influenced the theology and evangelistic practices of the Christian church, during his lifetime he was unknown beyond his immediate area. Even Josephus, the major historian of the day, does not refer to him in his writings. (Engaging God’s Word: Acts, Engage Bible Studies 2012, p.85) Page | 1 WEEK 1 WEEK 1 WEEK 1 WEEKWeek 3 WEEK 1 WEEK 1 WEEK 1 1 Getting started: In the two thousand years since his death and resurrection, millions have turned to Jesus. Lives have been transformed. Directions changed. But no conversion is more dramatic than that of Saul of Tarsus. His is the most famous in church history. This is the young man who approved of Stephen’s brutal death and then set out to single- handedly destroy the church. -

Timeline of the Book of Acts

TIMELINE OF THE BOOK OF ACTS Dates Reference Events Books Written Historical Events Roman Emperors c. 2 AD Acts 21:39 Saul born in Tarsus of Cilicia Augustus (27 BC‐14 AD) 7 AD Judea becomes a Roman Imperial province 14 AD Tiberius (14‐37 AD) 26 AD Pontius Pilate procurator of Judea 29 AD Acts 1‐2 Jesus is crucified under Pontius Pilate, Resurrection Appearances (after Passover) Ascension Birth of Church on Pentecost Acts 3 Lame man healed, Peter's 2nd sermon Acts 4 Peter & John before Sanhedrin Fellowship in Community 29‐31 AD Acts 5 Ananias & Sapphira Multitudes believe and many signs and wonders c. 29‐36 AD Acts 22:3; Phil 3:5 Saul in the school of Gamaliel, Jerusalem 31‐35 AD Acts 6‐7 Selection of 7 deacons Arrest and stoning of Stephen Saul present at Stephen's stoning 35‐36 AD Acts 8 Scattering of church: Philip in Samaria, Peter & John travel 36 AD Acts 9; II Cor 11:32 Saul's conversion on road to Aretas king of Damascus (9 BC‐40 AD) Damascus 36‐39 AD Gal 1:17 Saul in Damascus & Arabia for 3 years 39 AD Acts 9:20‐30 Saul's first visit to Jerusalem for Herod Agrippa appointed by Tiberius as Gaius (37‐41 AD) also 15 days, then to Tarsus king of Judea called Caligula 39‐43 AD Gal 1:21‐24 Saul preaches in Syria & Cilicia 39‐40 AD Acts 10 Peter preaches to Cornelius' household in Caesarea; first Gentiles believe 41 AD Herod Agrippa appointed by Claudius Claudius (41‐54 AD) ruler of ALL Judea (includes Samaria & other provinces) 41‐43 AD Acts 11:22‐26 Barnabas goes to Antioch 43‐44 AD Barnabas gets Saul from Tarsus, spends year in Antioch -

Acts 21:30 - 22:23

ACTS 21:30 - 22:23 Introduction: 1. An uproar from the Ephesian Jews, about Paul being in the temple, breaks out. The crowd grabs Paul, taking him out a door so he supposedly wouldn't pollute the temple any further. Of course, their intentions were to kill Paul - but not in the temple. II Kings 11:15 - But Jehoiada the priest commanded the captains of the hundreds, the officers of the host, and said unto them, Have her forth without the ranges: and him that followeth her kill with the sword. For the priest had said, Let her not be slain in the house of the LORD. 2. The religious Jews' zeal was inflamed by the false accusations about Paul. They believed them to be true and this infuriated the hyped-up crowd. They began to savagely beat Paul. They were so ea- ger to kill Paul that they don't even take him out of the city to stone him (like Stephen). They immedi- ately began to try to beat him to death on the spot! **They would have succeeded, but God intervened to protect his servant. A. Acts 21:30-36 - And all the city was moved, and the people ran together: and they took Paul, and drew him out of the temple: and forthwith the doors were shut. Acts 21:31 And as they went about to kill him, tidings came unto the chief captain of the band, that all Jerusalem was in an uproar. Acts 21:32 Who immediately took soldiers and centurions, and ran down unto them: and when they saw the chief captain and the soldiers, they left beating of Paul. -

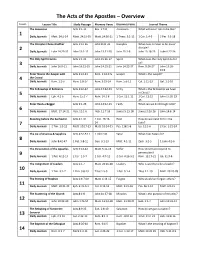

The Acts of the Apostles – Overview

The Acts of the Apostles – Overview Lesson Lesson Title Study Passage Memory Verse Discovery Focus Journal Theme The Ascension Acts 1:1-11 Rev. 1:7-8 Ascension What will Jesus’ return be like? 1 Daily Journals Matt. 24:1-14 Matt. 24:15-35 Matt. 24:36-51 1 Thess. 5:1-11 1 Cor. 1:4-9 2 Pet. 3:3-18 The Disciples Chose Another Acts 1:12-26 John 8:31-32 Disciples What does it mean to be Jesus’ 2 disciple? Daily Journals Luke 14:25-33 John 13:1-17 John 13:31-38 John 15:1-8 John 15:18-25 Luke 6:27-36 The Holy Spirit Comes Acts 2:1-21 John 15:26-27 Spirit What does the Holy Spirit do for 3 us? Daily Journals John 16:5-11 John 16:12-15 John 14:15-21 John 14:22-37 Rom. 8:26-27 John 15:26- 16:4 Peter Shares the Gospel with Acts 2:22-41 Rom. 1:16-17a Gospel What is the Gospel? 4 the Crowd Daily Journals Rom. 1:1-6 Rom. 1:8-17 Rom. 3:19-24 Rom. 5:6-11 Col. 1:21-23 Gal. 1:1-10 The Fellowship of Believers Acts 2:42-47 John 17:22-23 Unity What is the fellowship we have 5 in Christ? Daily Journals Eph. 4:1-6 Rom. 15:1-7 Rom. 14:1-8 1 Cor. 12:1-11 1 Cor. 12:12- John 17:20-23 26 Peter Heals a Beggar Acts 3:1-26 John 14:12-13 Faith What can we do through faith? 6 Daily Journals Matt.