Changing Faces: Immigrants and Diversity in the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shortage of Skilled Workers Looms in U.S. - Los Angeles Times

Shortage of skilled workers looms in U.S. - Los Angeles Times http://articles.latimes.com/2008/apr/21/local/me-immiglabor21 California | Local You are here: LAT Home > Articles > 2008 > April > 21 > California | Local Shortage of skilled workers looms in U.S. By Teresa Watanabe April 21, 2008 With baby boomers preparing to retire as the best educated and most skilled workforce in U.S. history, a growing chorus of demographers and labor experts is raising concerns that workers in California and the nation lack the critical skills needed to replace them. In particular, experts say, the immigrant workers needed to fill many of the boomer jobs lack the English-language skills and basic educational levels to do so. Many immigrants are ill-equipped to fill California’s fastest-growing positions, including computer software engineers, registered nurses and customer service representatives, a new study by the Washington-based Migration Policy Institute found. Immigrants – legal and illegal – already constitute almost half of the workers in Los Angeles County and are expected to account for nearly all of the growth in the nation’s working-age population by 2025 because native-born Americans are having fewer children. But the study, based largely on U.S. Census data, noted that 60% of the county’s immigrant workers struggle with English and one-third lack high school diplomas. The looming mismatch in the skills employers need and those workers offer could jeopardize the future economic vitality of California and the nation, experts say. Los Angeles County, the largest immigrant metropolis with about 3.5 million foreign-born residents, is at the forefront of this demographic trend. -

Plaintiffs Filed a Motion for Preliminary Injunction, Or in the Alternative

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA PHILIP KINSLEY, et al. Plaintiffs, Civil Action No. 1:21-cv-00962-JEB v. ANTONY J. BLINKEN, et al. PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION OR Defendants. SUMMARY JUDGMENT IN THE ALTERNATIVE AILA Doc. No. 21040834. (Posted 6/15/21) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION OR SUMMARY JUDGMENT IN THE ALTERNATIVE Pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65 and Local Civil Rule 65.1, Plaintiffs respectfully move the Court for a preliminary injunction, or in the alternative, pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56 and Local Civil Rule 7, summary judgment to enjoin Defendants from continuing a “no visa policy” in specific consulates as a means to implement suspensions on entry to the United States under Presidential Proclamations issued under 8 U.S.C. § 1182(f), Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA” ) § 212(f). The parties conferred and submitted a joint scheduling order consistent with the procedural approach for an expedited resolution of this matter. See ECF No. 14. The filing of this motion complies with the agreed upon schedule, though undersigned counsel understands the Court has yet to grant the parties’ motion. Id. Dated: June 11, 2021 Respectfully Submitted, __/s/ Jeff Joseph_ Jeff D. Joseph Joseph & Hall P.C. 12203 East Second Avenue Aurora, CO 80011 (303) 297-9171 [email protected] D.C. Bar ID: CO0084 Greg Siskind Siskind Susser PC 1028 Oakhaven Rd. Memphis, TN 39118 [email protected] D.C. Bar ID: TN0021 Charles H. Kuck Kuck Baxter Immigration, LLC 365 Northridge Rd, Suite 300 Atlanta, GA 30350 [email protected] AILA Doc. -

The Labor Department's Green-Card Test -- Fair Process Or Bureaucratic

The Labor Department’s Green-Card Test -- Fair Process or Bureaucratic Whim? Angelo A. Paparelli, Ted J. Chiappari and Olivia M. Sanson* Governments everywhere, the United States included, are tasked with resolving disputes in peaceful, functional ways. One such controversy involves the tension between American employers seeking to tap specialized talent from abroad and U.S. workers who value their own job opportunities and working conditions and who may see foreign-born job seekers as unwelcome competition. Given these conflicting concerns, especially in the current economic climate, this article will review recent administrative agency decisions involving permanent labor certification – a labor-market testing process designed to determine if American workers are able, available and willing to fill jobs for which U.S. employers seek to sponsor foreign-born staff so that these non-citizens can receive green cards (permanent residence). The article will show that the U.S. Department of Labor (“DOL”), the agency that referees such controversies, has failed to resolve these discordant interests to anyone’s satisfaction; instead the DOL has created and oversees the labor-market test – technically known as the Program Electronic Review Management (“PERM”) labor certification process – in ways that may suggest bureaucratic whim rather than neutral agency action. The DOL’s PERM process – the usual prerequisite1 for American businesses to employ foreign nationals on a permanent (indefinite) basis – is the method prescribed by the Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA”) for negotiating this conflict of interests in the workplace. At first blush, the statutorily imposed resolution seems reasonable, requiring the DOL to certify in each case that the position offered to the foreign citizen could not be filled by a U.S. -

Per-Country Limits on Permanent Employment-Based Immigration

Numerical Limits on Permanent Employment- Based Immigration: Analysis of the Per-country Ceilings Carla N. Argueta Analyst in Immigration Policy July 28, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42048 Numerical Limits on Employment-Based Immigration Summary The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) specifies a complex set of numerical limits and preference categories for admitting lawful permanent residents (LPRs) that include economic priorities among the criteria for admission. Employment-based immigrants are admitted into the United States through one of the five available employment-based preference categories. Each preference category has its own eligibility criteria and numerical limits, and at times different application processes. The INA allocates 140,000 visas annually for employment-based LPRs, which amount to roughly 14% of the total 1.0 million LPRs in FY2014. The INA further specifies that each year, countries are held to a numerical limit of 7% of the worldwide level of LPR admissions, known as per-country limits or country caps. Some employers assert that they continue to need the “best and the brightest” workers, regardless of their country of birth, to remain competitive in a worldwide market and to keep their firms in the United States. While support for the option of increasing employment-based immigration may be dampened by economic conditions, proponents argue it is an essential ingredient for economic growth. Those opposing increases in employment-based LPRs assert that there is no compelling evidence of labor shortages and cite the rate of unemployment across various occupations and labor markets. With this economic and political backdrop, the option of lifting the per-country caps on employment-based LPRs has become increasingly popular. -

Why the Securing America's Future Act, 2.0 Won't Fix the Farm Labor Crisis

WHY THE SECURING AMERICA’S FUTURE ACT, 2.0 WON’T FIX THE FARM LABOR CRISIS AREA OF CONCERN #1: CURRENT WORKFORCE The proposed single solution, a new H-2C program, will not provide a workable solution for our current workforce. While the SAF Act 2.0 does make a number of improvements that agriculture has been asking for over the past several months, it continues to lack provisions for an effective, stable transition in which we can be confident the current workforce will participate. SAF Act Provisions Why Ag Is Concerned Offers experienced, unauthorized agricultural workers At least half of the ~2 million farm workers hired the ability to participate in the H-2C guest worker each year lack proper status. Requiring initial program. This allows them to attain legal work status departure from the U.S. will lead to chaos for H-2C and the ability to travel to and from the United States. users and non-users alike, despite proposals for a “pre-certification” process addressing employer Requires unauthorized agricultural workers to eligibility. The average term of employment of the temporarily leave the U.S. in order to join the H-2C workforce exceeds 14 years. It is unlikely that program, which they must do within the first 12 months married falsely documented farm workers will of enactment of the final rules implementing the Act. voluntarily elect to join a program that increases the chances their immediate family will be deported. Once they are in the H-2C program, seasonal workers Production ag needs a stabilization period which will are required to depart the country every 24 months and allow current experienced workers to apply and be go through the visa process again. -

Instructions for the 2021 Diversity Immigrant Visa Program (Dv-2021)

UNCLASSIFIED INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE 2021 DIVERSITY IMMIGRANT VISA PROGRAM (DV-2021) Program Overview The Department of State annually administers the statutorily-mandated Diversity Immigrant Visa Program. Section 203(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) provides for a class of immigrants known as “diversity immigrants” from countries with historically low rates of immigration to the United States. For Fiscal Year 2021, 55,000 Diversity Visas (DVs) will be available. There is no cost to register for the DV program. Applicants who are selected in the program (selectees) must meet simple but strict eligibility requirements to qualify for a diversity visa. The Department of State determines selectees through a randomized computer drawing. The Department of State distributes diversity visas among six geographic regions, and no single country may receive more than seven percent of the available DVs in any one year. For DV-2021, natives of the following countries are not eligible to apply, because more than 50,000 natives of these countries immigrated to the United States in the previous five years: Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, China (mainland-born), Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Jamaica, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, South Korea, United Kingdom (except Northern Ireland) and its dependent territories, and Vietnam. Persons born in Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and Taiwan are eligible. Eligibility Requirement #1: Individuals born in countries whose natives qualify may be eligible to enter. If you were not born in an eligible country, there are two other ways you might be able to qualify. Was your spouse born in a country whose natives are eligible? If yes, you can claim your spouse’s country of birth – provided that both you and your spouse are named on the selected entry, are found eligible and issued diversity visas, and enter the United States simultaneously. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Immigration Compliance Alert

VEDDERPRICE ® November 2009 Immigration Compliance Alert ICE Increases I-9 Audit Actions foreign nationals in H-1B (Specialty Occupation) and L-1 (Intracompany Transferee) immigration status. The USCIS Fraud In July 2009, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detection and National Security unit (FDNS) has initiated these (ICE) notiS ed 652 businesses that they had been targeted visits as part of the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) for in-person inspections of their I-9 Employment Eligibility efforts to expand worksite enforcement. USCIS has hired a Veri cation Forms. This recent enforcement initiative is part of large number of private contractors to conduct thousands of the government’s efforts to hold employers accountable for their site visits and verify information from the I-129 petitions led hiring practices and ensure a legal workforce across the country. with the agency. John Morton, Assistant Secretary for ICE, has stated, “ICE is As part of these site visits, the FDNS assessors may visit committed to establishing a meaningful inspection program to the workplace unannounced or with very short notice. Typically, promote compliance with the law.” He added that the nationwide they will ask questions of nonimmigrant workers, administrative effort was a rst step in ICE’s long-term strategy to address personnel and supervisors. Most questions will directly relate and deter illegal employment by focusing on employers rather to the information submitted with the I-129 petitions in order to than on undocumented workers. In all of scal year 2008, ICE con rm accuracy. FDNS assessors may ask to review issued only 503 similar notices to employers. -

Threatening Immigrants: Cultural Depictions of Undocumented Mexican Immigrants in Contemporary Us America

THREATENING IMMIGRANTS: CULTURAL DEPICTIONS OF UNDOCUMENTED MEXICAN IMMIGRANTS IN CONTEMPORARY US AMERICA Katharine Lee Schaab A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2015 Committee: Jolie Sheffer, Advisor Lisa Hanasono Graduate Faculty Representative Rebecca Kinney Susana Peña © 2015 Katharine Schaab All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jolie Sheffer, Advisor This project analyzes how contemporary US cultural and legislative texts shape US society’s impression of undocumented (im)migrants and whether they fit socially constructed definitions of what it means to “be American” or part of the US national imaginary. I argue that (im)migrant-themed cultural texts, alongside legal policies, participate in racial formation projects that use racial logic to implicitly mark (im)migrants as outsiders while actively employing ideologies rooted in gender, economics, and nationality to rationalize (im)migrants’ exclusion or inclusion from the US nation-state. I examine the tactics anti- and pro-(im)migrant camps utilize in suppressing the role of race—particularly the rhetorical strategies that focus on class, nation, and gender as rationale for (im)migrants’ inclusion or exclusion—in order to expose the similar strategies governing contemporary US (im)migration thought and practice. This framework challenges dichotomous thinking and instead focuses on gray areas. Through close readings of political and cultural texts focused on undocumented (im)migration (including documentaries, narrative fiction, and photography), this project homes in on the gray areas between seemingly pro- and anti-(im)migrant discourses. I contend (im)migration-themed political and popular rhetoric frequently selects a specific identity marker (e.g. -

Diversity Visa “Green Card” Lottery to Open Soon

RESPONSIVE SOLUTIONS Diversity Visa “Green Card” Lottery to Open Soon Countries with high rates of immigration are NOT qualified. These Failure to obtain a visa to the US between October 1 and September typically include Brazil, China, the Dominican Republic, 30 of the government year following selection will result in El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Jamaica, Mexico, Poland, and disqualification from the program, so selected applicants will need the UK among others. By contrast, most African and European to act on their visa applications quickly. Although it’s possible to countries are typically eligible. Nationality is determined by the apply for the lottery from the US, those who are unlawfully present country of birth of the applicant, his or her spouse, or parents in the US will rarely be eligible to receive a green card. (provided certain requirements are met). FRAUD WARNING Last year, the government received over 14 million entries for the Every year, fraudulent websites pose as the official U.S. government 50,000 available visas. Counties with the highest number of winners site and charge applicants money to “register”. Be wary of anyone included Nigeria, Ukraine and Ethiopia. seeking to collect a registration or filing fee for assistance in HOW TO APPLY submitting an application. The government does not charge a fee for submitting the application. Only Internet sites that end with To enter the lottery, the foreign national must submit an electronic the .gov domain are official U.S. government websites. Others application through the official U.S. Department of State website should not be trusted, and in no case should you send any personal (http://travel.state.gov) during a specified time each year. -

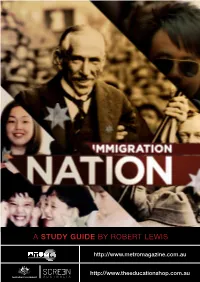

A STUDY GUIDE by Robert Lewis

A STUDY GUIDE BY ROBERT LEWIS http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au OVERVIEW OF FILM The series of three 54-minute episodes immigration program. Migrants from charts how the dream soon became war-torn Europe arrived en masse. It At the dawn of the twentieth century a nightmare for some. The insecuri- was social engineering on the grand- Australia was a social laboratory. ties of those at the helm meant that est of scales. The country would be A great experiment was underway at the start of the twentieth century fundamentally transformed forever. But to make this new country the most immigration policy was driven by fear the gatekeepers to the nation’s borders progressive and egalitarian nation in and racism, as well as by a vision had to take Australia and its people the world. of being a ‘British’ Australia. As the with them on this radical journey of White Australia Policy was developed change. The new arrivals had to be The country was busy initiating radical and enforced, many of the non-white white, and the dream was kept alive reforms, born of noble ideals, that residents were deported and barred through stealth and propaganda. The enshrined basic political freedoms and from entry. Vibrant communities were message was clear: ‘You’re welcome the rights of fairness and opportunity fractured and the Chinese population but on our terms and only if you adopt for all. At Federation in 1901, Australia dwindled dramatically. this country as your own.’ It was the seemed to stand as a beacon to the age of assimilation. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Sound Editing For A Nonfiction Or Reality Program (Single Or Multi-Camera) All In: The Fight For Democracy All In: The Fight For Democracy follows Stacey Abrams’s journey alongside those at the forefront of the battle against injustice. From the country’s founding to today, this film delves into the insidious issue of voter suppression - a threat to the basic rights of every American citizen. Allen v. Farrow Episode 2 As Farrow and Allen cement their professional legacy as a Hollywood power couple, their once close-knit family is torn apart by the startling revelation of Woody's relationship with Mia's college-aged daughter, Soon-Yi. Dylan details the abuse allegations that ignited decades of backlash, and changed her life forever. Amend: The Fight For America Promise Immigrants have long put their hope in America, but intolerant policies, racism and shocking violence have frequently trampled their dreams. American Masters Mae West: Dirty Blonde Rebel, seductress, writer, producer and sexual icon -- Mae West challenged the morality of our country over a career spanning eight decades. With creative and economic powers unheard of for a female entertainer in the 1930s, she “climbed the ladder of success wrong by wrong.” American Murder: The Family Next Door Using raw, firsthand footage, this documentary examines the disappearance of Shanann Watts and her children, and the terrible events that followed. American Oz (American Experience) Explore the life of L. Frank Baum, author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. By 1900, Baum had spent his life in pursuit of success.