Thread Level Parallelism(I)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Performance Evaluation of Cache-Coherent NUMA and COMA Architectures Abstract 1 Introduction

Comparative Performance Evaluation of Cache-Coherent NUMA and COMA Architectures Per Stenstromt, Truman Joe, and Anoop Gupta Computer Systems Laboratory Stanford University, CA 94305 Abstract machine. Currently, many research groups are pursuing the design and construction of such multiprocessors [12, 1, 10]. Two interesting variations of large-scale shared-memory ma- As research has progressed in this area, two interesting vari- chines that have recently emerged are cache-coherent mm- ants have emerged, namely CC-NUMA (cache-coherent non- umform-memory-access machines (CC-NUMA) and cache- uniform memory access machines) and COMA (cache-only only memory architectures (COMA). They both have dis- memory architectures). Examples of the CC-NUMA ma- tributed main memory and use directory-based cache coher- chines are the Stanford DASH multiprocessor [12] and the MIT ence. Unlike CC-NUMA, however, COMA machines auto- Alewife machine [1], while examples of COMA machines are matically migrate and replicate data at the main-memoty level the Swedish Institute of Computer Science’s Data Diffusion in cache-line sized chunks. This paper compares the perfor- Machine (DDM) [10] and Kendall Square Research’s KSR1 mance of these two classes of machines. We first present a machine [4]. qualitative model that shows that the relative performance is Common to both CC-NUMA and COMA machines are the primarily determined by two factors: the relative magnitude features of distributed main memory, scalable interconnection of capacity misses versus coherence misses, and the gramr- network, and directory-based cache coherence. Distributed hirity of data partitions in the application. We then present main memory and scalable interconnection networks are es- quantitative results using simulation studies for eight prtraUeI sential in providing the required scalable memory bandwidth, applications (including all six applications from the SPLASH while directory-based schemes provide cache coherence with- benchmark suite). -

Detailed Cache Coherence Characterization for Openmp Benchmarks

1 Detailed Cache Coherence Characterization for OpenMP Benchmarks Anita Nagarajan, Jaydeep Marathe, Frank Mueller Dept. of Computer Science, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695-7534 [email protected], phone: (919) 515-7889 Abstract models in their implementation (e.g., [6], [13], [26], [24], [2], [7]), and they operate at different abstraction levels Past work on studying cache coherence in shared- ranging from cycle-accuracy over instruction-level to the memory symmetric multiprocessors (SMPs) concentrates on operating system interface. On the performance tuning end, studying aggregate events, often from an architecture point work mostly concentrates on program analysis to derive op- of view. However, this approach provides insufficient infor- timized code (e.g., [15], [27]). Recent processor support for mation about the exact sources of inefficiencies in paral- performance counters opens new opportunities to study the lel applications. For SMPs in contemporary clusters, ap- effect of applications on architectures with the potential to plication performance is impacted by the pattern of shared complement them with per-reference statistics obtained by memory usage, and it becomes essential to understand co- simulation. herence behavior in terms of the application program con- In this paper, we concentrate on cache coherence simu- structs — such as data structures and source code lines. lation without cycle accuracy or even instruction-level sim- The technical contributions of this work are as follows. ulation. We constrain ourselves to an SPMD programming We introduce ccSIM, a cache-coherent memory simulator paradigm on dedicated SMPs. Specifically, we assume the fed by data traces obtained through on-the-fly dynamic absence of workload sharing, i.e., only one application runs binary rewriting of OpenMP benchmarks executing on a on a node, and we enforce a one-to-one mapping between Power3 SMP node. -

Computer Science 246 Computer Architecture Spring 2010 Harvard University

Computer Science 246 Computer Architecture Spring 2010 Harvard University Instructor: Prof. David Brooks [email protected] Dynamic Branch Prediction, Speculation, and Multiple Issue Computer Science 246 David Brooks Lecture Outline • Tomasulo’s Algorithm Review (3.1-3.3) • Pointer-Based Renaming (MIPS R10000) • Dynamic Branch Prediction (3.4) • Other Front-end Optimizations (3.5) – Branch Target Buffers/Return Address Stack Computer Science 246 David Brooks Tomasulo Review • Reservation Stations – Distribute RAW hazard detection – Renaming eliminates WAW hazards – Buffering values in Reservation Stations removes WARs – Tag match in CDB requires many associative compares • Common Data Bus – Achilles heal of Tomasulo – Multiple writebacks (multiple CDBs) expensive • Load/Store reordering – Load address compared with store address in store buffer Computer Science 246 David Brooks Tomasulo Organization From Mem FP Op FP Registers Queue Load Buffers Load1 Load2 Load3 Load4 Load5 Store Load6 Buffers Add1 Add2 Mult1 Add3 Mult2 Reservation To Mem Stations FP adders FP multipliers Common Data Bus (CDB) Tomasulo Review 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 LD F0, 0(R1) Iss M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 M6 M7 M8 Wb MUL F4, F0, F2 Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Ex Ex Ex Ex Wb SD 0(R1), F0 Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss M1 M2 M3 Wb SUBI R1, R1, 8 Iss Ex Wb BNEZ R1, Loop Iss Ex Wb LD F0, 0(R1) Iss Iss Iss Iss M Wb MUL F4, F0, F2 Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Ex Ex Ex Ex Wb SD 0(R1), F0 Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss M1 M2 -

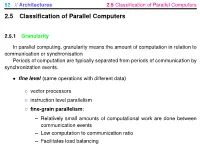

2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers

52 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.1 Granularity In parallel computing, granularity means the amount of computation in relation to communication or synchronisation Periods of computation are typically separated from periods of communication by synchronization events. • fine level (same operations with different data) ◦ vector processors ◦ instruction level parallelism ◦ fine-grain parallelism: – Relatively small amounts of computational work are done between communication events – Low computation to communication ratio – Facilitates load balancing 53 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers – Implies high communication overhead and less opportunity for per- formance enhancement – If granularity is too fine it is possible that the overhead required for communications and synchronization between tasks takes longer than the computation. • operation level (different operations simultaneously) • problem level (independent subtasks) ◦ coarse-grain parallelism: – Relatively large amounts of computational work are done between communication/synchronization events – High computation to communication ratio – Implies more opportunity for performance increase – Harder to load balance efficiently 54 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.2 Hardware: Pipelining (was used in supercomputers, e.g. Cray-1) In N elements in pipeline and for 8 element L clock cycles =) for calculation it would take L + N cycles; without pipeline L ∗ N cycles Example of good code for pipelineing: §doi =1 ,k ¤ z ( i ) =x ( i ) +y ( i ) end do ¦ 55 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers Vector processors, fast vector operations (operations on arrays). Previous example good also for vector processor (vector addition) , but, e.g. recursion – hard to optimise for vector processors Example: IntelMMX – simple vector processor. -

Balanced Multithreading: Increasing Throughput Via a Low Cost Multithreading Hierarchy

Balanced Multithreading: Increasing Throughput via a Low Cost Multithreading Hierarchy Eric Tune Rakesh Kumar Dean M. Tullsen Brad Calder Computer Science and Engineering Department University of California at San Diego {etune,rakumar,tullsen,calder}@cs.ucsd.edu Abstract ibility of SMT comes at a cost. The register file and rename tables must be enlarged to accommodate the architectural reg- A simultaneous multithreading (SMT) processor can issue isters of the additional threads. This in turn can increase the instructions from several threads every cycle, allowing it to clock cycle time and/or the depth of the pipeline. effectively hide various instruction latencies; this effect in- Coarse-grained multithreading (CGMT) [1, 21, 26] is a creases with the number of simultaneous contexts supported. more restrictive model where the processor can only execute However, each added context on an SMT processor incurs a instructions from one thread at a time, but where it can switch cost in complexity, which may lead to an increase in pipeline to a new thread after a short delay. This makes CGMT suited length or a decrease in the maximum clock rate. This pa- for hiding longer delays. Soon, general-purpose micropro- per presents new designs for multithreaded processors which cessors will be experiencing delays to main memory of 500 combine a conservative SMT implementation with a coarse- or more cycles. This means that a context switch in response grained multithreading capability. By presenting more virtual to a memory access can take tens of cycles and still provide contexts to the operating system and user than are supported a considerable performance benefit. -

Analysis and Optimization of I/O Cache Coherency Strategies for Soc-FPGA Device

Analysis and Optimization of I/O Cache Coherency Strategies for SoC-FPGA Device Seung Won Min Sitao Huang Mohamed El-Hadedy Electrical and Computer Engineering Electrical and Computer Engineering Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Illinois University of Illinois California State Polytechnic University Urbana, USA Urbana, USA Ponoma, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jinjun Xiong Deming Chen Wen-mei Hwu IBM T.J. Watson Research Center Electrical and Computer Engineering Electrical and Computer Engineering Yorktown Heights, USA University of Illinois University of Illinois [email protected] Urbana, USA Urbana, USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Unlike traditional PCIe-based FPGA accelerators, However, choosing the right I/O cache coherence method heterogeneous SoC-FPGA devices provide tighter integrations for different applications is a challenging task because of between software running on CPUs and hardware accelerators. it’s versatility. By choosing different methods, they can intro- Modern heterogeneous SoC-FPGA platforms support multiple I/O cache coherence options between CPUs and FPGAs, but these duce different types of overheads. Depending on data access options can have inadvertent effects on the achieved bandwidths patterns, those overheads can be amplified or diminished. In depending on applications and data access patterns. To provide our experiments, we find using different I/O cache coherence the most efficient communications between CPUs and accelera- methods can vary overall application execution times at most tors, understanding the data transaction behaviors and selecting 3.39×. This versatility not only makes designers hard to decide the right I/O cache coherence method is essential. -

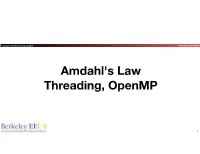

Amdahl's Law Threading, Openmp

Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver Amdahl's Law Threading, OpenMP 1 Big Idea: Amdahl’s (Heartbreaking) Law Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver • Speedup due to enhancement E is Exec time w/o E Speedup w/ E = ---------------------- Exec time w/ E • Suppose that enhancement E accelerates a fraction F (F <1) of the task by a factor S (S>1) and the remainder of the task is unaffected Execution Time w/ E = Execution Time w/o E × [ (1-F) + F/S] Speedup w/ E = 1 / [ (1-F) + F/S ] 2 Big Idea: Amdahl’s Law Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver Speedup = 1 (1 - F) + F Non-speed-up part S Speed-up part Example: the execution time of half of the program can be accelerated by a factor of 2. What is the program speed-up overall? 1 1 = = 1.33 0.5 + 0.5 0.5 + 0.25 2 3 Example #1: Amdahl’s Law Speedup w/ E = 1 / [ (1-F) + F/S ] Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver • Consider an enhancement which runs 20 times faster but which is only usable 25% of the time Speedup w/ E = 1/(.75 + .25/20) = 1.31 • What if its usable only 15% of the time? Speedup w/ E = 1/(.85 + .15/20) = 1.17 • Amdahl’s Law tells us that to achieve linear speedup with 100 processors, none of the original computation can be scalar! • To get a speedup of 90 from 100 processors, the percentage of the original program that could be scalar would have to be 0.1% or less Speedup w/ E = 1/(.001 + .999/100) = 90.99 4 Amdahl’s Law If the portion of Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 the program that Wawrzynek and Weaver can be parallelized is small, then the speedup is limited The non-parallel portion limits the performance 5 Strong and Weak Scaling Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver • To get good speedup on a parallel processor while keeping the problem size fixed is harder than getting good speedup by increasing the size of the problem. -

Chapter 5 Thread-Level Parallelism

Chapter 5 Thread-Level Parallelism Instructor: Josep Torrellas CS433 Copyright Josep Torrellas 1999, 2001, 2002, 2013 1 Progress Towards Multiprocessors + Rate of speed growth in uniprocessors saturated + Wide-issue processors are very complex + Wide-issue processors consume a lot of power + Steady progress in parallel software : the major obstacle to parallel processing 2 Flynn’s Classification of Parallel Architectures According to the parallelism in I and D stream • Single I stream , single D stream (SISD): uniprocessor • Single I stream , multiple D streams(SIMD) : same I executed by multiple processors using diff D – Each processor has its own data memory – There is a single control processor that sends the same I to all processors – These processors are usually special purpose 3 • Multiple I streams, single D stream (MISD) : no commercial machine • Multiple I streams, multiple D streams (MIMD) – Each processor fetches its own instructions and operates on its own data – Architecture of choice for general purpose mps – Flexible: can be used in single user mode or multiprogrammed – Use of the shelf µprocessors 4 MIMD Machines 1. Centralized shared memory architectures – Small #’s of processors (≈ up to 16-32) – Processors share a centralized memory – Usually connected in a bus – Also called UMA machines ( Uniform Memory Access) 2. Machines w/physically distributed memory – Support many processors – Memory distributed among processors – Scales the mem bandwidth if most of the accesses are to local mem 5 Figure 5.1 6 Figure 5.2 7 2. Machines w/physically distributed memory (cont) – Also reduces the memory latency – Of course interprocessor communication is more costly and complex – Often each node is a cluster (bus based multiprocessor) – 2 types, depending on method used for interprocessor communication: 1. -

Computer Hardware Architecture Lecture 4

Computer Hardware Architecture Lecture 4 Manfred Liebmann Technische Universit¨atM¨unchen Chair of Optimal Control Center for Mathematical Sciences, M17 [email protected] November 10, 2015 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 Reading List • Pacheco - An Introduction to Parallel Programming (Chapter 1 - 2) { Introduction to computer hardware architecture from the parallel programming angle • Hennessy-Patterson - Computer Architecture - A Quantitative Approach { Reference book for computer hardware architecture All books are available on the Moodle platform! Computer Hardware Architecture 1 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 UMA Architecture Figure 1: A uniform memory access (UMA) multicore system Access times to main memory is the same for all cores in the system! Computer Hardware Architecture 2 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 NUMA Architecture Figure 2: A nonuniform memory access (UMA) multicore system Access times to main memory differs form core to core depending on the proximity of the main memory. This architecture is often used in dual and quad socket servers, due to improved memory bandwidth. Computer Hardware Architecture 3 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 Cache Coherence Figure 3: A shared memory system with two cores and two caches What happens if the same data element z1 is manipulated in two different caches? The hardware enforces cache coherence, i.e. consistency between the caches. Expensive! Computer Hardware Architecture 4 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 False Sharing The cache coherence protocol works on the granularity of a cache line. If two threads manipulate different element within a single cache line, the cache coherency protocol is activated to ensure consistency, even if every thread is only manipulating its own data. -

Parallel Generation of Image Layers Constructed by Edge Detection

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 13, Number 10 (2018) pp. 7323-7332 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com Speed Up Improvement of Parallel Image Layers Generation Constructed By Edge Detection Using Message Passing Interface Alaa Ismail Elnashar Faculty of Science, Computer Science Department, Minia University, Egypt. Associate professor, Department of Computer Science, College of Computers and Information Technology, Taif University, Saudi Arabia. Abstract A. Elnashar [29] introduced two parallel techniques, NASHT1 and NASHT2 that apply edge detection to produce a set of Several image processing techniques require intensive layers for an input image. The proposed techniques generate computations that consume CPU time to achieve their results. an arbitrary number of image layers in a single parallel run Accelerating these techniques is a desired goal. Parallelization instead of generating a unique layer as in traditional case; this can be used to save the execution time of such techniques. In helps in selecting the layers with high quality edges among this paper, we propose a parallel technique that employs both the generated ones. Each presented parallel technique has two point to point and collective communication patterns to versions based on point to point communication "Send" and improve the speedup of two parallel edge detection techniques collective communication "Bcast" functions. The presented that generate multiple image layers using Message Passing techniques achieved notable relative speedup compared with Interface, MPI. In addition, the performance of the proposed that of sequential ones. technique is compared with that of the two concerned ones. In this paper, we introduce a speed up improvement for both Keywords: Image Processing, Image Segmentation, Parallel NASHT1 and NASHT2. -

CS650 Computer Architecture Lecture 10 Introduction to Multiprocessors

NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture CS650 Computer Architecture Lecture 10 Introduction to Multiprocessors and PC Clustering Andrew Sohn Computer Science Department New Jersey Institute of Technology Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 1/15 12/7/2003 A. Sohn NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture Key Issues Run PhotoShop on 1 PC or N PCs Programmability • How to program a bunch of PCs viewed as a single logical machine. Performance Scalability - Speedup • Run PhotoShop on 1 PC (forget the specs of this PC) • Run PhotoShop on N PCs • Will it run faster on N PCs? Speedup = ? Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 2/15 12/7/2003 A. Sohn NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture Types of Multiprocessors Key: Data and Instruction Single Instruction Single Data (SISD) • Intel processors, AMD processors Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) • Array processor • Pentium MMX feature Multiple Instruction Single Data (MISD) • Systolic array • Special purpose machines Multiple Instruction Multiple Data (MIMD) • Typical multiprocessors (Sun, SGI, Cray,...) Single Program Multiple Data (SPMD) • Programming model Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 3/15 12/7/2003 A. Sohn NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture Shared-Memory Multiprocessor Processor Prcessor Prcessor Interconnection network Main Memory Storage I/O Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 4/15 12/7/2003 A. Sohn NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture Distributed-Memory Multiprocessor Processor Processor Processor IO/S MM IO/S MM IO/S MM Interconnection network IO/S MM IO/S MM IO/S MM Processor Processor Processor Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 5/15 12/7/2003 A. -

High-Performance Message Passing Over Generic Ethernet Hardware with Open-MX Brice Goglin

High-Performance Message Passing over generic Ethernet Hardware with Open-MX Brice Goglin To cite this version: Brice Goglin. High-Performance Message Passing over generic Ethernet Hardware with Open-MX. Parallel Computing, Elsevier, 2011, 37 (2), pp.85-100. 10.1016/j.parco.2010.11.001. inria-00533058 HAL Id: inria-00533058 https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00533058 Submitted on 5 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. High-Performance Message Passing over generic Ethernet Hardware with Open-MX Brice Goglin INRIA Bordeaux - Sud-Ouest – LaBRI 351 cours de la Lib´eration – F-33405 Talence – France Abstract In the last decade, cluster computing has become the most popular high-performance computing architec- ture. Although numerous technological innovations have been proposed to improve the interconnection of nodes, many clusters still rely on commodity Ethernet hardware to implement message passing within parallel applications. We present Open-MX, an open-source message passing stack over generic Ethernet. It offers the same abilities as the specialized Myrinet Express stack, without requiring dedicated support from the networking hardware. Open-MX works transparently in the most popular MPI implementations through its MX interface compatibility.