Euonymus Fortunei

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

PRE Evaluation Report for Euonymus Alatus

PRE Evaluation Report -- Euonymus alatus Plant Risk Evaluator -- PRE™ Evaluation Report Euonymus alatus -- Texas 2017 Farm Bill PRE Project PRE Score: 16 -- Reject (high risk of invasiveness) Confidence: 71 / 100 Questions answered: 19 of 20 -- Valid (80% or more questions answered) Privacy: Public Status: Submitted Evaluation Date: September 21, 2017 This PDF was created on August 13, 2018 Page 1/18 PRE Evaluation Report -- Euonymus alatus Plant Evaluated Euonymus alatus Image by Chris Barton Page 2/18 PRE Evaluation Report -- Euonymus alatus Evaluation Overview A PRE™ screener conducted a literature review for this plant (Euonymus alatus) in an effort to understand the invasive history, reproductive strategies, and the impact, if any, on the region's native plants and animals. This research reflects the data available at the time this evaluation was conducted. Summary Euonymus alatus is naturalized across much of Eastern North America. It is a 1 to 4 meter tall shrub which an produce thickets in forest understory, displacing native vegetation. Seed production is prolific and dispersed by birds. General Information Status: Submitted Screener: Kim Taylor Evaluation Date: September 21, 2017 Plant Information Plant: Euonymus alatus If the plant is a cultivar, how does its behavior differs from its parent's? This evaluation is for the species, not a particular cultivar. Regional Information Region Name: Texas Page 3/18 PRE Evaluation Report -- Euonymus alatus Climate Matching Map To answer four of the PRE questions for a regional evaluation, a climate map with three climate data layers (Precipitation, UN EcoZones, and Plant Hardiness) is needed. These maps were built using a toolkit created in collaboration with GreenInfo Network, USDA, PlantRight, California-Invasive Plant Council, and The Information Center for the Environment at UC Davis. -

1. EUONYMUS Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 197

Fl. China 11: 440–463. 2008. 1. EUONYMUS Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 197. 1753 [“Evonymus”], nom. cons. 卫矛属 wei mao shu Ma Jinshuang (马金双); A. Michele Funston Shrubs, sometimes small trees, ascending or clambering, evergreen or deciduous, glabrous, rarely pubescent. Leaves opposite, rarely also alternate or whorled, entire, serrulate, or crenate, stipulate. Inflorescences axillary, occasionally terminal, cymose. Flowers bisexual, 4(or 5)-merous; petals light yellow to dark purple. Disk fleshy, annular, 4- or 5-lobed, intrastaminal or stamens on disk; anthers longitudinally or obliquely dehiscent, introrse. Ovary 4- or 5-locular; ovules erect to pendulous, 2(–12) per locule. Capsule globose, rugose, prickly, laterally winged or deeply lobed, occasionally only 1–3 lobes developing, loculicidally dehiscent. Seeds 1 to several, typically 2 developing, ellipsoid; aril basal to enveloping seed. Two subgenera and ca. 130 species: Asia, Australasia, Europe, Madagascar, North America; 90 species (50 endemic, one introduced) in China. Euonymus omeiensis W. P. Fang (J. Sichuan Univ., Nat. Sci. Ed. 1: 38. 1955) was described from Sichuan (Emei Shan, Shishungou, ca. 1300 m). This putative species was misdiagnosed; it is a synonym of Reevesia pubescens Masters in the Sterculiaceae (see Fl. China 12: 317. 2007). The protologue describes the fruit as having bracts. The placement of Euonymus tibeticus W. W. Smith (Rec. Bot. Surv. India 4: 264. 1911), described from Xizang (3000–3100 m) and also occurring in Bhutan (Lhakhang) and India (Sikkim), is unclear, as only a specimen with flower buds is available. Euonymus cinereus M. A. Lawson (in J. D. Hooker, Fl. Brit. India 1: 611. 1875) was described from India. -

Euonymus Europaeus

Euonymus europaeus COMMON NAME Spindle tree FAMILY Celastraceae FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Exotic STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE EUOEUR HABITAT Terrestrial. FEATURES Much-branched glabrous, deciduous shrub or small tree up to 6m high. Bark grey & smooth. Twigs green, quadrangular, smooth, not winged. Leaves opposite, ovate-lanceolate to elliptic, acute or acuminate, crenate, usually turning red in autumn, 2–10cm long; petiole 6–12mm long. Cymes 2–15-flowered, pedunculate, dichotomous. Buds greenish, usually 4- angled; flowers usually 4-merous, 8–10mm diam.; petals greenish-yellow, generally oblong, widely separated. Capsule 4-lobed, deep pink, exposing the bright orange aril after opening. (- Webb et. al., 1988) FLOWERING November, December Euonymus europaeus. Photographer: Nic Singers FLOWER COLOURS Green, Yellow FRUITING March to May YEAR NATURALISED 1958 ORIGIN Europe ETYMOLOGY euonymus: One possible explanation is this genus is named after Euonymus europaeus. Photographer: John Smith-Dodsworth Euonyme, the mother of the Furies (vengeance deities in Greek mythology) because of the irritating properties of this plant. Another explanation is that the name is simply from the Greek eu ‘good’ and onoma ‘name’, meaning ‘a name of good repute’. Reason For Introduction Ornamental Life Cycle Comments Perennial. Long-lived seed bank - more than a year (Carol West, pers. comm.). Reproduction The species is gynodioecious (2 sexual morphs: 1 strictly female and the other, termed male, producing some seed) with both sexes established in wild populations (Webb et al., 1988). Dispersal Birds (Webb et al., 1988). Poisonous plant: All parts of this tree are poisonous including the pink fruits with orange seed. MORE INFORMATION https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/flora/species/euonymus-europaeus/. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Invasive Landscape Plants in Arkansas

Invasive Landscape Plants in Arkansas Janet B. Carson Extension Horticulture Specialist Not all Landscape Plants are invasive Invasive plants are not all equally invasive. An invasive plant has the ability to thrive and spread aggressively outside its natural range. Top 10 Arkansas Landscape Invasives Alphabetically 1. Bamboo Phyllostachys species 2. Bradford Pears Pyrus calleryana ‘Bradford’ They are coming up everywhere! 3. English Ivy Hedera helix 4. Japanese Honeysuckle Lonicera japonica 5. Kudzu Pueraria montana 6. Mimosa Albizia julibrissin 7. Privet Ligustrum sinense Privet is the most invasive plant in Arkansas! 8. Running Monkey Grass Liriope spicata 9. Large leaf vinca Vinca major 10. Wisteria Wisteria floribunda Other Invasive Landscape Plants The following plants have been invasive in some landscape situations, and should be used with caution. They are more invasive under certain soil and weather conditions. Bishop’s Weed Aegopodium podagraria Ajuga Ajuga reptans Garlic Chives Allium tuberosum Devil’s Walking Stick Aralia spinosa Ardisia Ardisia japonica Artemesia Artemisia vulgaris Artemisia absinthium 'Oriental Limelight' Trumpet Creeper Campsis radicans Sweet Autumn Clematis Clematis terniflora Mexican Hydrangea Clereodendron bungei Wild Ageratum Conoclinium coelestinum Queen Ann’s Lace Daucus carota Russian Olive Elaeagnus angustifolia Horsetail - Scouring Rush Equisetum hyemale Wintercreeper Euonymus Euonymus fortunei Carolina Jessamine Gelsemium sempervirens Ground Ivy Glechoma hederacea Chameleon Plant Houttuynia cordata -

Celastraceae

Species information Abo ut Reso urces Hom e A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Celastraceae Family Profile Celastraceae Family Description A family of about 94 genera and 1400 species, worldwide; 22 genera occur naturally in Australia. Genera Brassiantha - A genus of two species in New Guinea and Australia; one species occurs naturally in Australia. Simmons et al (2012). Celastrus - A genus of 30 or more species, pantropic; two species occur naturally in Australia. Jessup (1984). Denhamia - A genus of about 17 species in the Pacific and Australia; about 15 species occur in Australia. Cooper & Cooper (2004); McKenna et al (2011); Harden et al (2014); Jessup (1984); Simmons (2004). Dinghoua - A monotypic genus endemic to Australia. Simmons et al (2012). Elaeodendron - A genus of about 80 species, mainly in the tropics and subtropics particularly in Africa; two species occur naturally in Australia. Harden et al. (2014); Jessup (1984) under Cassine; Simmons (2004) Euonymus - A genus of about 180 species, pantropic, well developed in Asia; one species occur naturally in Australia. Hou (1975); Jessup (1984); Simmons et al (2012). Gymnosporia - A genus of about 100 species in the tropics and subtropics, particularly Africa; one species occurs naturally in Australia. Jordaan & Wyk (1999). Hedraianthera - A monotypic genus endemic to Australia. Jessup (1984); Simmons et al (2012). Hexaspora - A monotypic genus endemic to Australia. Jessup (1984). Hippocratea - A genus of about 100 species, pantropic extending into the subtropics; one species occurs naturally in Australia. -

Guide to the Euonymus of New York City

New York City EcoFlora Guide to the Euonymus (Euonymus) of New York City Euonymus is a genus of 130–140 species in the mostly tropical Celastraceae (Staff-Tree) family. The family comprises about 95 genera and 1,350 species. Only three genera occur in the northern hemisphere, Euonymus, Celastrus and Parnassia, all three found or once found in New York City. Euonymus species occur nearly worldwide with most species native to eastern Asia. They are trees, shrubs or woody vines, the stems often angled or winged, sometimes climbing by adventitious roots; leaves deciduous or evergreen, opposite, the blades simple, margins crenate or toothed; inflorescences terminal or axillary; flowers in small clusters, petals usually green, sometimes white or purple; fruit usually brightly colored, lobed capsules; seeds enveloped in brightly colored tissue (aril), often contrasting with the fruit wall. Euonymus (as well as most members of the Celastraceae family) can often be recognized by “gestalt”. The leaves and often the stems too have a distinctive, but somewhat variable yellow-green color that is hard to describe but nearly unlike any other plants. The leaves are usually leathery, and almost always have distinctively scalloped (crenate) margins (the margins rarely completely smooth or toothed). There are four species native to North America, one species endemic to California, Oregon and Washington (Euonymus occidentalis); a predominately Midwestern species (Euonymus obovatus); a widespread northeastern species (Euonymus atropurpureus) and a widespread southeastern species (Euonymus americanus). Two species are indigenous to New York City. The predominately southeastern US species, Euonymus americanus, American Strawberry Bush is endangered in New York State. -

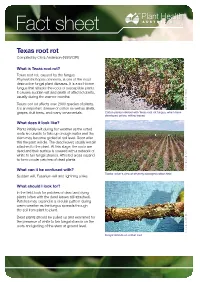

Texas Root Rot Compiled by Chris Anderson (NSW DPI)

Fact sheet Texas root rot Compiled by Chris Anderson (NSW DPI) What is Texas root rot? Texas root rot, caused by the fungus Phymatotrichopsis omnivora, is one of the most destructive fungal plant diseases. It is a soil-borne fungus that attacks the roots of susceptible plants. It causes sudden wilt and death of affected plants, usually during the warmer months. Texas root rot affects over 2000 species of plants. It is an important disease of cotton as well as alfalfa, Chris Anderson, I&I NSW grapes, fruit trees, and many ornamentals. Cotton plants infected with Texas root rot fungus, which have developed yellow, wilting leaves What does it look like? Plants initially wilt during hot weather as the rotted roots are unable to take up enough water and the stem may become girdled at soil level. Soon after this the plant will die. The dead leaves usually remain attached to the plant. At this stage, the roots are dead and their surface is covered with a network of white to tan fungal strands. Affected areas expand to form circular patches of dead plants. What can it be confused with? Chris Anderson, I&I NSW Tractor driver’s view of severely damaged cotton field Sudden wilt, Fusarium wilt and lightning strike. What should I look for? In the field, look for patches of dead and dying plants (often with the dead leaves still attached). Patches may expand in a circular pattern during warm weather as the fungus spreads through the soil from plant to plant. Dead plants should be pulled up and examined for the presence of white to tan fungal strands on the roots and girdling of the stem at ground level. -

Vascular Plant Inventory and Ecological Community Classification for Cumberland Gap National Historical Park

VASCULAR PLANT INVENTORY AND ECOLOGICAL COMMUNITY CLASSIFICATION FOR CUMBERLAND GAP NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK Report for the Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories: Appalachian Highlands and Cumberland/Piedmont Networks Prepared by NatureServe for the National Park Service Southeast Regional Office March 2006 NatureServe is a non-profit organization providing the scientific knowledge that forms the basis for effective conservation action. Citation: Rickie D. White, Jr. 2006. Vascular Plant Inventory and Ecological Community Classification for Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Durham, North Carolina: NatureServe. © 2006 NatureServe NatureServe 6114 Fayetteville Road, Suite 109 Durham, NC 27713 919-484-7857 International Headquarters 1101 Wilson Boulevard, 15th Floor Arlington, Virginia 22209 www.natureserve.org National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Atlanta Federal Center 1924 Building 100 Alabama Street, S.W. Atlanta, GA 30303 The view and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. This report consists of the main report along with a series of appendices with information about the plants and plant (ecological) communities found at the site. Electronic files have been provided to the National Park Service in addition to hard copies. Current information on all communities described here can be found on NatureServe Explorer at www.natureserveexplorer.org. Cover photo: Red cedar snag above White Rocks at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Photo by Rickie White. ii Acknowledgments I wish to thank all park employees, co-workers, volunteers, and academics who helped with aspects of the preparation, field work, specimen identification, and report writing for this project. -

Celastraceae (Bittersweet Family) Traits, Key, & Comparison Chart Genus Traits of Parnassia (Grass-Of-Parnassus)

Celastraceae (Bittersweet Family) Traits, Key, & Comparison Chart © S.J. Meades. Flora of Newfoundland and Labrador (Jan. 2020) Traits of Parnassia (Celastraceae)................................................................................................... 1 Key .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Comparison Chart .......................................................................................................................... 3 References ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Genus Traits of Parnassia (grass-of-Parnassus) [Parnassia is the only genus of the Celastraceae Family in NL] • Herbaceous plants with basal rosettes of petiolate leaves and 0 or 1 sessile cauline leaf; stems and leaves are glabrous (without hairs). • Flowers solitary, terminal on erect stems, bisexual, and 5-merous. • Flowers have 5 green sepals, 5 white petals with prominent veins, 5 stamens (maturing sequentially), and a single pistil. • Five staminodia (modified sterile stamens; singular: staminodium) are situated opposite the petals and alternate with the fertile stamens. Each staminodium has 3–27 slender segments that terminate in a spherical yellow gland. • The pistil has an ovoid, superior ovary, ivory white or green, which has 4 carpels but only 1 locule (interior chamber); stigmas are 4 and sessile; styles are lacking. • The fruit -

Comparison of Different Classifications on the Celastraceae

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICLJLTURE AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE NORTHEASTERN REGlON AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH CENTER BELTSVILLE. MARYLAND 20705 Novenber 7, 1974 / Subject: ConpadSon of Different Classifications on the Celastraceae in Africa with Discussions on the Status of Gymnosporia and Other Genera To : R. E. Perdue, Jr., Chief ,.. Medicinal Plant Resources ~aboratory Currently, the taxonomy of the Celastraceae is in a state of confusion. A few recent revisions limited mostly ,to political boundaries, have helped to clarify the systematics in a few genera; however, the continued disagreement among generic relationships seems to make it nore difficult for the non-specialist. Because of special efforts to procure plant samples in this family, frequent synonomy has led to confusion as well as duplica- tion, especially in Africa where a number of samples have been received from floristically related countries in which different authorities are recogcized for the Celastracean Flora. This report, primarily, will 'deal with the systematic problems of the African Celasrrtseae. Until recently, the Hippocrateaceae was treated as a separate family from the Celastraceae (Smith, 1940; Loesener, 1942; Wilczek, 1960; Hallee, 1962). L Robson (1965, 1966), Ding Hou (1963, 1964), Blakelock (1958), and Codd (1972) have united the Hippocrateaceae with the Celastraceae; but, their reasons for uniting the two families are not in agreement. The Celastraceae is believed by Codd and Kobson to comprise about 60 to 70 genera, but Ding Hou has indicated that there are about 90 genera. For the purpose of identifying two major complexes, which taxonomists are not in agreement, I will refer to the Celastraceae and Hippocrateaceae as two separate families.