The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1973 Education, Music Copyright By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dmitri Smirnov / Biography

Dmitri Smirnov - Biography - Dmitri Smirnov was born in Minsk in 2 November 1948, where his parents were active as opera singers. His family later moved to Central Asia, first to Ulan-Ude in the Burjati Autonomous Republic, then to Frunse, the capital city of Kirghiz Republic, where Smirnov spent most of his childhood. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory from 1967 until 1972 with Nikolai Sedelnikov, instrumentation with Edison Denissov and analysis with Yuri Cholopov. During this time, in 1970, he first made contact with the Webern pupil Philip Hershkovitz, who had moved from Vienna to Moscow and whose private teaching had a great influence on Soviet composers. From 1973 until 1980 Smirnow worked as an editor at the publishers “Sovietski Kompositor.” He was active as a freelance composer from 1981 until 1993. After winning first prize at a competition of the International Harp Week in Maastricht with his Solo for Harp in 1976, his music began to gain increased international recognition. Thus his opera “Tiriel” received its premiere in 1989 in Freiburg, and the chamber opera “Thel’s Complaint” at the Almeida Festival in London. The world premiere of his First Symphony “The Seasons” also took place in 1989 at the Tanglewood Festival, and the oratorio “A Song of Liberty” was premiered in Leeds by the BBC Philharmonic in 1993. Smirnov has made his permanent residence in Great Britain since 1991. In 1992 he received a stipend from St. John College Cambridge and from 1993 to 1997 held the position of Guest Professor and Composer in Residence at the University of Keele, together with his wife, the composer Elena Firssova. -

Eight Poems in One Movement for Solo Voice and Orchestra by Ned

SUN (1966): EIGHT POEMS IN ONE MOVEMENT FOR SOLO VOICE AND ORCHESTRA BY NED ROREM: BACKGROUND, ANALYSIS, AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE Soohee Jung, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Jeffrey Snider, Major Professor and Chair, Division of Vocal Studies Paula Homer, Committee Member Elvia Puccinelli, Committee Member Lynn Eustis, Director of Graduate Studies, College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Jung, Soohee. Sun (1966): Eight Poems in One Movement for Solo Voice and Orchestra by Ned Rorem: Background, Analysis, and Performance Guide. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2012, 71 pp., 17 musical examples, 2 figures, bibliography, 39 titles. The purpose of the document is to present Ned Rorem’s Sun (1966): Eight Poems in One Movement for Solo Voice and Orchestra. The eight songs are “To the Sun,” “Sun of the Sleepless,” “Dawn,” “Day,” “Catafalque,” “Full Many a Glorious Morning,” “Sundown Lights,” and “From What Can I Tell My Bones?” The document is divided into four main chapters: 1) Background; 2) Poet and Poem Background; 3) Musical Analysis; 4) Performance Guide. Chapter 1 contains biographical information on Ned Rorem, and basic information of the work, Sun. Here, a relationship between the eight songs is presented. Chapter 2 discusses biography of poet and background of the poem. The poetry is examined to determine the theme and to identify imagery, and metaphor. Chapter 3 offers detailed musical analysis for each of the eight songs and interludes. -

Music for Thirteen Instruments and Percussion

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1969 Music for Thirteen Instruments and Percussion Yong Jin Kim Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Music at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Kim, Yong Jin, "Music for Thirteen Instruments and Percussion" (1969). Masters Theses. 4089. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4089 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #]-,. To: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. Subject: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is rece1v1ng a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements. Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. NAY 1969 Date ' I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University '•not allow my thesis be reproduced because ��- Date Author /LB1861.C57XK493>V1>C2/ MUSIC FOR THIRTEEN INSTRUMENTS AND P�RCUSSION (TITLE) BY YONG JIN KIM THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF OF MAS!'ER ARTS IN MUSIC IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE ADVISER 16; lfb I ( DA'fE 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to ackrlowledg e his indebtedness to all members of this Graduate Coumittaea Dr. -

Leihmaterial Verlagsvertretungen Für Den Deutschsprachigen Raum Auswahl Aus Den Katalogen - Stand: Juli 2016

Leihmaterial Verlagsvertretungen für den deutschsprachigen Raum Auswahl aus den Katalogen - Stand: Juli 2016 - Komponist / Titel Instrumentation Dauer / Verlag (verschiedene) 2 Farrago of BritishS Folksongs (R Farnon) 2(=picc).2.2.2-2.2.0.0-timp(vib).perc(1)-pft-harp-strings Subito s Shaker Suite (RayS Wright) strings 9' Subito Aaltoila, Heikki 1 Akselin ja Elinan Fhäävalssi 1.1.2.2-2.2.3.0-perc(1):timp/vib-strings 7' Fennica Wedding Waltz Abels, Michael 2 Dance for Martin’sS Dream 2.picc.2(1).2(II=Ebcl).2-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2)-harp-strings 13' Subito 2 Frederick’s FablesS 2(II=picc).2(II=corA).2(II=bcl).2-2.2.2.0-timp.perc(2)- 37' Subito harp-cel-strings 2 Global Warming S 2.picc.2(II=corA).2.2-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2)-harp-strings 8' Subito 2 Gospel ArrangementsS 2(1).2.2.2-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(3).pft-gtr(opt)-strings 50' Subito Adam, Adolph Charles 2 O Holy Night O 2 fl, ob, 2 cl, bn, 2 hn, hp, str 6' OUP Cantique de Noel p O Holy Night [Db]O (Wilberg) picc, 2 fl, 2 ob, 2 cl in A, 2 bn, 4 hn, org (opt), str 4' OUP Addison, John Inventions O OUP f Serenade for WindO Quintet and Harp fl, ob, cl, bn, hn, hp 18' OUP t Wellington Suite O timp, 2 perc, str [2 solo horns, solo piano] 16' OUP Adler, Samuel Songs with WindsO 10' OUP for solo voice and wind quintet Aho, Kalevi 1 Before we all drownedF 11.asax.heckelphone.22/2111/1perc/hp/str Fennica Chamber SymphonyF No.1 13' Fennica a Chamber SymphonyF No.3 alto saxophone and 20 strings 30' Fennica 2 Chinese Songs F 2.2.2.1-2.2.1.1-perc-harp-strings 20' Fennica ,2 Concerto for BassoonF and Orchestra 2(I=picc)2(II=ob.d'amore)22(II=c.fag)-3221-02-pf+cel-str 37' Fennica Perc. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. Order Number 8717608 The decomposer’s art: Ideas of music in the poetry of Wallace Stevens Boring, Barbara Holmes, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1987 Copyright ©1987 by Boring, Barbara Holmes. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. ZeebRd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

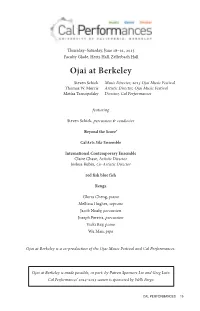

Ojai at Berkeley

Thursday–Saturday, June 18–21, 2015 Faculty Glade, Hertz Hall, Zellerbach Hall Ojai at Berkeley Steven Schick Music Director, OMNR Ojai Music Festival Thomas W. Morris Artistic Director, Ojai Music Festival Matías Tarnopolsky Director, Cal Performances featuring Steven Schick, percussion & conductor Beyond the Score® CalArts Sila Ensemble Interna tional Contemporary Ensemble Claire Chase, Artistic Director Joshua Rubin, Co-Artistic Director red fish blue fish Renga Gloria Cheng, piano Mellissa Hughes, soprano Jacob Nissly, percussion Joseph Pereira, percussion Vicki Ray, piano Wu Man, pipa Ojai at Berkeley is a co-production of the Ojai Music Festival and Cal Performances. Ojai at Berkeley is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Liz and Greg Lutz. Cal Performances’ OMNQ–OMNR season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 15 Thursday–Saturday, June 18–20, 2015 Faculty Glade, Hertz Hall, Zellerbach Hall Ojai at Berkeley FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Thursday, June ?F, @>?C, Dpm Welcome: Cal Performances Artistic and Faculty Glade Executive Director Matías Tarnopolsky Outdoor Concert: Sila: The Breath of the World Fpm Program 1: Beyond the Score®: A Pierre Dream— Zellerbach Hall Pierre Boulez: A Portrait and Debussy Friday, June ?G, @>?C, Cpm Talk: Steven Schick and Claire Chase conduct Hertz Hall Patio an audience participation event to include Lei Liang’s Trans Epm Program 2: Presenting Steven Schick Hertz Hall Xenakis, Stockhausen, Lang, Globokar, Auzet ?>pm Program 3: Debussy, Boulez, works for pipa Hertz Hall Saturday, June @>, @>?C, ??am Program 4: Messiaen, Ravel, Boulez Hertz Hall @:A>pm Program 5: Boulez, Bartók Hertz Hall Cpm Community Response Panel: A conversation with Hertz Hall Patio composer Jimmy Lopez, musicologist William Quillen, conductor Lynne Morrow, and musician Amy X Neuberg Fpm Program 6: Wolfe, Harrison, Chávez, Ginastera On Saturday, June OM, lunch and dinner will be provided by Grace Street catering. -

AUTHOR Music for Preschool

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 060 948 PS 005 475 AUTHOR Adkins Dorothy C.; And Others TITLE Music for Preschool: Accompanied byS ngbook. INSTITUTION Hawaii Univ., Honolulu. SPONS AGENCY Office of Economic Opportunity,Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Sep 71 NOTE 175p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Audiovisual Aids; *Curriculum Design; Educational Objectives; Guides; *Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; Lesson Plans; *MusicEducation; Planning; *Preschool Children; Scheduling;Tape Recordings; *Teaching Techniques; Textbooks ABSTRACT A curriculum for preschoolers in musiceducation is presented. It consists of three sections:Introduction, General Teaching Suggestions, and Materials andActivities. The Introduction outlines the objectives of theprogram and presents ideas relating to scheduling, planning and selection of materials,as well as the use of music in fostering general preschoolaims. Section II clarifies overall techniques in teaching musictO children. Materials and Activities contains suggestedsongs, recordings, and activities that the teacher should select when planningthe program.(Author/CK) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEACTI-1. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY MUSIC FOR PRESCHOOL Accompanied by SONGBOOK Dorothy C. Adkins, Professor and Research-- Marvin Greenberg, Associate Professor and Music Consultant Annette Okimoto, Junior Researcher Betty Elrod, Assistant in Research Patricia MacDonald, Assistant in Resear h The research reported herein was performed pursuantto Grant Number 9929 with the United States Office of Economic Opportunity. Contractors undertaking such projects under Government sponsorship are encouraged to expressfreely their professional judgment on the conduct of the project. -

My Blake Note Was Inessential.”3 Our Publishers Were Pleased and De- Cided to Print Both Our Scores

ARTICLE instrumental characteristics and a predilection for lyrical phrases. The ending, when the first violin emerges from a lovely texture of celesta, vibraphone, bells and the higher stringed instruments is a moment of transcendent magic. It also exemplifies the economy of Smirnov’s writing: not a My Blake note was inessential.”3 Our publishers were pleased and de- cided to print both our scores. By Dmitri Nikolaevich Smirnov1 2 Soon Kathleen Raine (illus. 1) invited all of us for a cup of Dmitri Nikolaevich Smirnov (dmitrismirnov@ tea. The tea party lasted more than three hours, and we had hotmail.co.uk) is a Russian and British composer, born a long and wonderful talk about Blake. I told her about my in Minsk into a family of opera singers and now living two operas based on Blake’s early prophetic poems and in St. Albans, Hertfordshire. He studied at the Moscow asked for advice about what to choose for my next Blake Conservatory 1967–72 and in 1979 was blacklisted as project. With no hesitation she showed me Blake’s illustra- one of “Khrennikov’s Seven” at the Sixth Congress of tions for the Book of Job, which decorated the walls above the Union of Soviet Composers for unapproved partici- her staircase, and said that they would be wonderful sub- pation in some festivals of Soviet music in the West. He jects for a dramatic musical work. As a present she gave me was one of the founders of Russia’s new ACM (Associ- a few of her books about Blake, as well as her own Selected ation for Contemporary Music), established in Moscow Poems and Autobiographies. -

Leihmaterial Verlagsvertretungen Im Deutschsprachigen Raum Auswahl Aus Den Katalogen - Stand: Dezember 2009

Leihmaterial Verlagsvertretungen im deutschsprachigen Raum Auswahl aus den Katalogen - Stand: Dezember 2009 - Komponist / Titel Instrumentation Dauer / Verlag Aaltoila, Heikki 1 Akselin ja Elinan häävalssiF 1.1.2.2-2.2.3.0-perc(1):timp/vib-strings 7' Fennica Wedding Waltz Adam, Adolph Charles 2 O Holy Night O 2 fl, ob, 2 cl, bn, 2 hn, hp, str 6' OUP Cantique de Noel Der Toreador (Schickele/Rumpel)C Chappell Buffo-Oper in 2 Akten Addison, John Inventions O OUP f Serenade for WindO Quintet and Harp fl, ob, cl, bn, hn, hp 18' OUP t Wellington Suite O timp, 2 perc, str [2 solo horns, solo piano] 16' OUP Aho, Kalevi a Chamber SymphonyF No. 3 alto saxophone and 20 strings 30' Fennica 2 Concerto for ClarinetF and Orchestra 2222/3221.barhn/01/1/str 30' Fennica 2 Concerto for FluteF and Orchestra 2222/32.barhn.21/02/1/str - soloist: flute (also alto flute) 31' Fennica 2 Concerto for SaxophoneF Quartet and Orchestra 2.2.2.2.-2.2.2.0-perc-strings 28' Fennica Kellot 3 Hyönteiselämää F 3.2.heckelphone.3.asax.3-4.3.3.barhn.1-timp.perc(3)- 165' Fennica Insect Life (after Karel and Josef Capek) 2harp-strings-tape S The Key F Soloist: baritone Fennica Dramatic Monologue for Baritone and Chamber Orchestra fl/ca/bcl/bn/2hn/barhn/pianino/1perc/vn/va/vc/db Quintett F Fennica 3 The Rejoicing of theF Deep Water 3.3.3.asax.3-4.3.3.1-timp.perc-strings 10' Fennica Den Djupa Vattens Fest S Salaisuuksien KirjaF Soloists, mixed choir and orchestra: Fennica The book of secrets - Opera in One Act and Four Scenes 32.heck.33/4331/4perc/hp.pf(cel)/str 2 Symphony No. -

Film Music and Film Genre

Film Music and Film Genre Mark Brownrigg A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Stirling April 2003 FILM MUSIC AND FILM GENRE CONTENTS Page Abstract Acknowledgments 11 Chapter One: IntroductionIntroduction, Literature Review and Methodology 1 LiteratureFilm Review Music and Genre 3 MethodologyGenre and Film Music 15 10 Chapter Two: Film Music: Form and Function TheIntroduction Link with Romanticism 22 24 The Silent Film and Beyond 26 FilmTheConclusion Function Music of Film Form Music 3733 29 Chapter Three: IntroductionFilm Music and Film Genre 38 FilmProblems and of Genre Classification Theory 4341 FilmAltman Music and Genre and GenreTheory 4945 ConclusionOpening Titles and Generic Location 61 52 Chapter Four: IntroductionMusic and the Western 62 The Western and American Identity: the Influence of Aaron Copland 63 Folk Music, Religious Music and Popular Song 66 The SingingWest Cowboy, the Guitar and other Instruments 73 Evocative of the "Indian""Westering" Music 7977 CavalryNative and American Civil War WesternsMusic 84 86 PastoralDown andMexico Family Westerns Way 89 90 Chapter Four contd.: The Spaghetti Western 95 "Revisionist" Westerns 99 The "Post - Western" 103 "Modern-Day" Westerns 107 Impact on Films in other Genres 110 Conclusion 111 Chapter Five: Music and the Horror Film Introduction 112 Tonality/Atonality 115 An Assault on Pitch 118 Regular Use of Discord 119 Fragmentation 121 Chromaticism 122 The A voidance of Melody 123 Tessitura in extremis and Unorthodox Playing Techniques 124 Pedal Point -

OF ORCHESTRATION THESI Presented to the Graduate Council

-7 AN ANALYSIS OF MAURICE RAVEL' STECHNIQUE OF ORCHESTRATION THESI Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Murray Augustus Allman, B. M. E. Denton, Texas August, 195$ 4"Mm-mill pgpqmpm TABLE 0F CyONTNT Page LIST OF B ES . - - - - - - - - - . .IV I)A S ' 1-7LS1 2v P~ LIST oF ILLUST rTOQ * . * . * . * . , * . 4 . * V t BIOGRP t ICAL KE C F UrICE E .. II. OTO F PIANOcoMPOSTIO - , - , * * I fnaL sis of chestration 4 t enuet Antimaue , jalysis of Orchestrati- of Pavane our une Infante DbffuLte rAnlyis of Orchtttion M, it nere tL ye Analysis of Orchestration of pictures aan ELo iiLtionT -i II.LARGE ORCHTESTRA-,1LWRK.... *. Anlysi W 0rchkiestration of )pOdi OrchQtrti o Bolero A s of Orchestration of is at Chlo' ti I is - Ara-ysis of Orchestration of La se Anays0i1s of station of ILtroduction Analysis 'ouo of Orchestration ofL Slihehra'ncro .. zaid-r e Ana]lyvsis of Or chetain fOcerdD psano et Orchestre or AnaLysis of~Orchestr-tion of concertoo for the Left and for Piano ar:d Orci'estra Conclusion ~~ BIBLIOAPTYV . - - - - - - - - - - - - 132 iii LIST OF TABLES T oble Page I. Comparison of Rt vel0s Orchestra to that of Orchard Wagner . - . - . 13 II *Ratios of Real Parts to Doubled Parts in Ma a ue a . - - - - - I. >atios of Real Parts to Doubled Parts- . i. Or IV. 01rt s 1F RearilParts tCo Doubled .Pnarts . i.n " r.,".- - - - - - - . 65 V. Avcrage Rtioi of Real Parts to Doubled Pars of Each Sectio0 >?on of R ns-*dieE . -

The Influence of Janissary Music Upon Selected Composition of Ludwig

THE INFLUENCE OF JANISSARY MUSIC UPON SELECTED CO]):!POSITIONS OF LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN A Thesis · .Presented to the Faculty of the School of Humanities Department of Music Morehead State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master. of Music Education by Jerry Len Weakley January, 1969 AP,, ♦ 'tV:9f HF"'i::-S 1<Jf;./3 W3G/,i Accepted by the faculty of the School of Humanities, Morehe.ad ·State University, •in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of ~lusic Education degree. \ \._J Master I s Committee ://4~.&:!~~Jt/{_~,1=,),~f/~ ~~~~C::-J+::_j.~'A, Januar 23. 1969. 1date) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . .. 1 II. THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITIONS OF TERMS USED • • 6 The Problem • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Statement of the problem •• • • • • • • • 6 Importance of the study • • • • • • • • • 6 Limitations • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Hypothesis •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Definitions of Term~ Used • • • • • • • • • 7 Janissary Music • • • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Janissaries • • • e • • • • • • • • • • • 7 III. REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE. • • • • • • • • • • 9 IV. PROCEDURE AND RESULTS • • • • • • • • • • • • 10 Procedure • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 10 Results . • . • • . • . • • • • 10 v. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION •••••••• • • • • 22 BIBLIOGRAPHY ••••••• • • . ~ . • • • • • • • 24 LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE PAGE 1. Excerpt from Beethoven's "Turkish March" • • 13 2. Excerpt from the "Marcia: Rule Britania" from Beethoven's "Battle of Vittoria" • • 15 3. Excerpt from the "Marcia: Marlborough" from Beethoven's "Bat.tle of Vittoria" • • 17 4. Excerpt from :the final movement of Beethoven's "Ninth Symphony", • • • • • • 19 5, Excerpt from the final movement of Beethoven's "Ninth Sy~phony" • • • • • • • 20 ., CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Janissary music was a type of Turkish military music which was popular at one time in European . l armies. It consisted of music for brass and percussion 2 instruments (triangle, cymbals, and bass drum).