New York Non-Native Plant Invasiveness Ranking Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manhattan 41 North Main Gimlet Chocolate Sazerac Smoking Apple Rum Fashion Hop Collins New Pal Highland Park Rosemary Paloma

SPIRITS MANHATTAN 12 RUM FASHION 10 rye whiskey • carpano antica • taylor adgate port wine • white rum • muddled orange & cherry • vanilla syrup • almond syrup cio ciaro amaro • aromatic bitters • brandied cherry HOP COLLINS 10 41 NORTH MAIN 12 gin • fresh lemon juice • IPA • honey CLASSICS vodka • cucumber • basil • simple syrup • fresh lime juice NEW PAL 12 GIMLET 12 SIGNATURES gin • aperol • lillet blanc • grapefruit bitters vodka • elderower liqueur • fresh lime juice HIGHLAND PARK 12 CHOCOLATE SAZERAC 10 rye whiskey • fresh lemon juice • simple syrup • port wine • egg white rye whiskey • crème de cocoa • simple syrup • absinthe rinse SMOKING APPLE 14 ROSEMARY PALOMA 14 mezcal • apple pie moonshine • apple cider • fresh lime juice tequila • fresh grapefruit juice • rosemary simple syrup • rosemary salt rim DRAUGHT BEER PINT or TASTING FLIGHT // 8 LOCAL BEER SELECTIONS your server would be happy to describe our beer on tap this evening. BOTTLED BEER MICHELOB ULTRA 5 SAM ADAMS SEASONAL 6 PERONI 6 COORS LIGHT 5 YUENGLING LAGER 6 STELLA ARTOIS 6 LABATT BLUE 5 HEINEKEN 6 GUINNESS DRAUGHT 6 LABATT BLUE LIGHT 5 BALLAST POINT GRAPEFRUIT SCULPIN 6 BECK’S N/A 5 CORONA 5 WAGNER VALLEY IPA 6 MODELO 6 BLUE MOON 5 1911 CIDER SEASONAL 6 BROOKLYN LAGER 6 WINE SPARKLING DESTELLO • Cava Brut Reserva • Catelonia, Spain G 10 B 32 ZARDETTO • Prosecco NV • Veneto, Italy G 11 B 38 RUFFINO • Moscato D’Asti DOCG • Piedmont, Italy G 10 B 32 BY THE BY GLASS ROSÉ JOLIE FOLLE • Grenache-Syrah • Provence, France G 12 B 46 WHITES HOUSE • Rotating Selection G 9 SAUVION -

Prohibited Species: What NOT to Plant

Prohibited Species: What NOT to Plant e new NJDEP Coastal Management Zone blooms and large red rose hips, this is a non-native Regulations specify that dunes in New Jersey will be plant and should be avoided when restoring native planted with native species only. What follows is a list dunes. Beach plum and bayberry are native plants with of non-indigenous and/or non-native plant species that high habitat value that would be better choices for should NOT be planted on dunes. planting in areas in where rugosa rose is being considered. An alternative rose would be Virginia rose European beachgrass (Ammophila arenaria ) – (Rosa virginiana). While this is not available locally, it is available online and from catalogs for import from California and Salt cedar (Tamarisk sp.) – Its extreme salt tolerance Oregon but would be devastating to the local ecology makes it a common choice for shore gardeners. While if planted here. this plant is not too invasive in dry areas, it is a real threat in riparian areas and planting it should be Dunegrass (Leymus mollis) – is is a native species avoided. to North America but is not indigenous as far south as New Jersey. It occurs from Massachusetts through the Shore juniper (Juniperus conferta) – is species is a Canadian Maritimes and in the Pacific Northwest. non-native, creeping evergreen groundcover and is is plant would not be adapted to our hot, dry used primarily as an ornamental landscaping summers and would not thrive locally. foundation plant. Blue lyme grass (Leymus arenaria) – is is a non- Japanese Black Pine (Pinus thunbergii) – native, ornamental, coastal landscaping grass that is Japanese black pine is highly used by landscapers in not an appropriate plant species for dune stabilization. -

Front Door Brochure

012_342020 A 4 4 l b H a n o y l l , a N n Y d A 1 2 v 2 e 2 n 9 u - e 0 0 0 1 For more information about the FRONT DOOR, call your local Front Door contact: Finger Lakes ..............................................855-679-3335 How Can I Western New York ....................................800-487-6310 Southern Tier ..................................607-771-7784, Ext. 0 Get Services? Central New York .....................315-793-9600, Ext. 603 The Front Door North Country .............................................518-536-3480 Capital District ............................................518-388-0398 Rockland County ......................................845-947-6390 Orange County .........................................845-695-7330 Taconic ..........................................................844-880-2151 Westchester County .................................914-332-8960 Brooklyn .......................................................718-642-8576 Bronx .............................................................718-430-0757 Manhattan ..................................................646-766-3220 Queens ..........................................................718-217-6485 Staten Island .................................................718-982-1913 Long Island .................................................631-434-6000 Individuals with hearing impairment: use NY Relay System 711 (866) 946-9733 | NY Relay System 711 www.opwdd.ny.gov Identify s s s s s Contact Information Determine s Assessment Develop Services Support The Front -

Our Last Speaker Before the Break Is Don Schall

IMPROVING WILDLIFE HABITAT ON COASTAL BANKS R DUNES THROUGH VEGETATIVE PI.ANTS Don Schall, Senior Biologist, ENSR, Sagamore Beach, MA MR. O' CONNELL: Our last speaker before the break is Don Schall. Don serves as a Senior Biologist at ENSR'sSagamore Beach, Massachusetts facility. Don has thirty years of professional experience in conservation education, wetland mitigation planning, vernal pool investigation, and plant and wildlife habitat assessment. Don has served as a project manager for numerous coastal and inland wetland resource area evaluations, marine and freshwater plant and animal inventory, and wetlands impact assess- ment. Prior to joining ENSR, Don was the education curator for the Cape Cod Museum of Natu- ral History in Brewster, and presently serves as a member of the Brewster Conservation Commis- sion and the State Task Force on rare plant conservation. Don has a BA in biology from Seton Hall University and a Master of Forest Science from Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Don's going to tell us how we can enhance wildlife habitat using vegetation on dunes and coastal banks. MR. SCHALL: Thank you. I think time should be spent, and maybe it' ll come up in the discussion, talking to the permitting of the activities that are proposed. I mean, it's not difficult to come up with an engi- neering solution, and perhaps it's a little more difficult to come up with a soft solution that addresses the issues for coastal erosion. The permitting process is part of the time frame that should be considered for some of these processes and, although it was briefly touched on earlier, it can be quite long. -

Nashville District

Nashville District ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Proposed Master Plan Update Old Hickory Lake January 2016 For Further Information, Contact: Kim Franklin U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Nashville District 110 Ninth Ave South, Room A-405 Nashville, Tennessee 37203 PROPOSED MASTER PLAN UPDATE OLD HICKORY LAKE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 2 PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION ..................................................................... 1 3 ALTERNATIVES ...................................................................................................... 2 3.1 Full Implementation of Proposed Master Plan Update .................................... 2 3.2 No-Action ............................................................................................................ 2 4 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES ........... 3 4.1 Project History and Setting ............................................................................... 3 4.2 Climate, Physiography, Topography, Geology, and Soils .............................. 4 4.3 Existing Conditions ............................................................................................ 4 4.3.1 Full Implementation of Proposed Master Plan Update ...................................... 5 4.3.2 No-Action .......................................................................................................... 5 4.4 Aquatic Environment ........................................................................................ -

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List This PDF document provides additional information to supplement the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM) Coastal Landscaping website. The plants listed below are good choices for the rugged coastal conditions of Massachusetts. The Coastal Beach Plant List, Coastal Dune Plant List, and Coastal Bank Plant List give recommended species for each specified location (some species overlap because they thrive in various conditions). Photos and descriptions of selected species can be found on the following pages: • Grasses and Perennials • Shrubs and Groundcovers • Trees CZM recommends using native plants wherever possible. The vast majority of the plants listed below are native (which, for purposes of this fact sheet, means they occur naturally in eastern Massachusetts). Certain non-native species with specific coastal landscaping advantages that are not known to be invasive have also been listed. These plants are labeled “not native,” and their state or country of origin is provided. (See definitions for native plant species and non-native plant species at the end of this fact sheet.) Coastal Beach Plant List Plant List for Sheltered Intertidal Areas Sheltered intertidal areas (between the low-tide and high-tide line) of beach, marsh, and even rocky environments are home to particular plant species that can tolerate extreme fluctuations in water, salinity, and temperature. The following plants are appropriate for these conditions along the Massachusetts coast. Black Grass (Juncus gerardii) native Marsh Elder (Iva frutescens) native Saltmarsh Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) native Saltmeadow Cordgrass (Spartina patens) native Sea Lavender (Limonium carolinianum or nashii) native Spike Grass (Distichlis spicata) native Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) native Plant List for a Dry Beach Dry beach areas are home to plants that can tolerate wind, wind-blown sand, salt spray, and regular interaction with waves and flood waters. -

Rosa L.: Rose, Briar

Q&R genera Layout 1/31/08 12:24 PM Page 974 R Rosaceae—Rose family Rosa L. rose, briar Susan E. Meyer Dr. Meyer is a research ecologist at the USDA Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station Shrub Sciences Laboratory, Provo, Utah Growth habit, occurrence, and uses. The genus and act as seed dispersers (Gill and Pogge 1974). Wild roses Rosa is found primarily in the North Temperate Zone and are also utilized as browse by many wild and domestic includes about 200 species, with perhaps 20 that are native ungulates. Rose hips are an excellent source of vitamin C to the United States (table 1). Another 12 to 15 rose species and may also be consumed by humans (Densmore and have been introduced for horticultural purposes and are nat- Zasada 1977). Rose oil extracted from the fragrant petals is uralized to varying degrees. The nomenclature of the genus an important constituent of perfume. The principal use of is in a state of flux, making it difficult to number the species roses has clearly been in ornamental horticulture, and most with precision. The roses are erect, clambering, or climbing of the species treated here have been in cultivation for many shrubs with alternate, stipulate, pinnately compound leaves years (Gill and Pogge 1974). that have serrate leaflets. The plants are usually armed with Many roses are pioneer species that colonize distur- prickles or thorns. Many species are capable of clonal bances naturally. The thicket-forming species especially growth from underground rootstocks and tend to form thick- have potential for watershed stabilization and reclamation of ets. -

Native Nebraska Woody Plants

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS NATIVE NEBRASKA WOODY PLANTS Trees (Genus/Species – Common Name) 62. Atriplex canescens - four-wing saltbrush 1. Acer glabrum - Rocky Mountain maple 63. Atriplex nuttallii - moundscale 2. Acer negundo - boxelder maple 64. Ceanothus americanus - New Jersey tea 3. Acer saccharinum - silver maple 65. Ceanothus herbaceous - inland ceanothus 4. Aesculus glabra - Ohio buckeye 66. Cephalanthus occidentalis - buttonbush 5. Asimina triloba - pawpaw 67. Cercocarpus montanus - mountain mahogany 6. Betula occidentalis - water birch 68. Chrysothamnus nauseosus - rabbitbrush 7. Betula papyrifera - paper birch 69. Chrysothamnus parryi - parry rabbitbrush 8. Carya cordiformis - bitternut hickory 70. Cornus amomum - silky (pale) dogwood 9. Carya ovata - shagbark hickory 71. Cornus drummondii - roughleaf dogwood 10. Celtis occidentalis - hackberry 72. Cornus racemosa - gray dogwood 11. Cercis canadensis - eastern redbud 73. Cornus sericea - red-stem (redosier) dogwood 12. Crataegus mollis - downy hawthorn 74. Corylus americana - American hazelnut 13. Crataegus succulenta - succulent hawthorn 75. Euonymus atropurpureus - eastern wahoo 14. Fraxinus americana - white ash 76. Juniperus communis - common juniper 15. Fraxinus pennsylvanica - green ash 77. Juniperus horizontalis - creeping juniper 16. Gleditsia triacanthos - honeylocust 78. Mahonia repens - creeping mahonia 17. Gymnocladus dioicus - Kentucky coffeetree 79. Physocarpus opulifolius - ninebark 18. Juglans nigra - black walnut 80. Prunus besseyi - western sandcherry 19. Juniperus scopulorum - Rocky Mountain juniper 81. Rhamnus lanceolata - lanceleaf buckthorn 20. Juniperus virginiana - eastern redcedar 82. Rhus aromatica - fragrant sumac 21. Malus ioensis - wild crabapple 83. Rhus copallina - flameleaf (shining) sumac 22. Morus rubra - red mulberry 84. Rhus glabra - smooth sumac 23. Ostrya virginiana - hophornbeam (ironwood) 85. Rhus trilobata - skunkbush sumac 24. Pinus flexilis - limber pine 86. Ribes americanum - wild black currant 25. -

Multiflora Rose, Rosa Multiflora Thunb. Rosaceae

REGULATORY HORTICULTURE [Vol. 9, No.1-2] Weed Circular No. 6 Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture April & October 1983 Bureau of Plant Industry Multiflora Rose, Rosa multiflora Thunb. Rosaceae. Robert J. Hill I. Nomenclature: A) Rosa multiflora Thunb. (Fig. 1); B) Multiflora rose; C) Synonyms: Rosa Dawsoniana Hort., R. polyantha Sieb. & Zucc., R. polyanthos Roessia., R. thyrsiflora Leroy, R. intermedia, Carr., and R. Wichurae Kock. Fig. 1. Multiflora rose. A) berrylike hips, B)leaf, note pectinate stipules (arrow), C) stem (cane). II. History: The genus Rosa is a large group of plants comprised of about 150 species, of which one-third are indigenous to America. Gray's Manual of Botany (Fernald 1970) lists 24 species (13 native; 11 introduced, 10 of these fully naturalized) for our range. Gleason and Cronquist (l968) cite 19 species (10 introductions). The disagreement in the potential number of species encountered in Pennsylvania arises from the confused taxonomy of a highly variable and freely crossing group. In fact, there are probably 20,000 cultivars of Rosa known. Bailey (1963) succinctly states the problem: "In no other genus, perhaps, are the opinions of botanists so much at variance in regard to the number of species." The use of roses by mankind has a long history. The Romans acquired a love for roses from the Persians. After the fall of Rome, roses were transported by the Benedictine monks across the Alps, and by the 700's AD garden roses were growing in southern France. The preservation and expansion of these garden varieties were continued by monasteries and convents from whence they spread to castle gardens and gradually to more humble, secular abodes. -

Swing Through

Swing Through 20m Swing Through is an interactive agility garden that connects the user to Canada’s diverse landscape, as well as its major economic industry. The garden is a series of thirteen finished lumber posts that dangle from a large steel structure, creating “tree swings”. On the swings are climbing holds where visitors can use the holds to climb up and across the tree swings. Directly under the tree swings are thirteen colour-coordinated stumps that give the user an extra boost, if needed. The thirteen timber tree swings represent Canada’s ten provinces and three territories by using wood from the official provincial and territorial trees. Surrounding this structure of Canadian trees is a garden divided into thirteen sections displaying the native plants of each province and territory. This representative regional plantings encompassing the swings, creating a soft edge. 10m Swing Through allows visitors to touch, smell, and play with the various YT NT NU BC AB SK MB ON QC NL NB PE NS natural elements that make our country so green, prosperous and beautiful. PLAN | 1:75 Yukon Nunavut Alberta Manitoba Quebec New Brunswick Nova Scotia Tree: Subapline fir, Abies lasiocarpa Tree: Balsam Poplar, Populus balsamifera Tree: Lodgepole pine, Pinus contorta Tree: Balsam fir, Abies balsamea Tree: Yellow birch, Betula alleghaniensis Tree: Balsam fir, Abies balsamea Tree: Red spruce, Picea rubens Plants: Epilobium angustifolium, Plants: Saxifraga oppositifolia, Rubus Plants: Rosa acicularis Prunus virginiana, Plants: Pulsatilla ludoviciana, -

BCH Beverage Menu

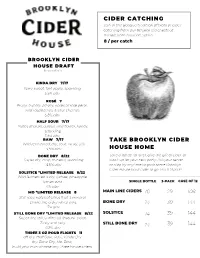

CIDER CATCHING Join in the Basque tradition of txotx or cider catching from our 80 year old chestnut barrels from Asturias, Spain. 8 / per catch BROOKLYN CIDER HOUSE DRAFT 8oz pours/bottle KINDA DRY 7/17 Semi-sweet, tart apple, sparkling 5.5% abv ROSÉ 7 Fruity, bubbly, off-dry, notes of rose petal, wild raspberries, & sour cherries 5.8% abv HALF SOUR 7/17 Notes of pickled pear, wild flower, honey, sparkling 5.8% abv RAW 7/17 TAKE BROOKLYN CIDER Wild fermented, dry, sour, funky, still 6.9% abv HOUSE HOME BONE DRY 8/22 Save a bottle for later, give the gift of cider, or Super dry, crisp, mineral, sparkling stock up for your next party. Ask your server 6.9% abv or stop by anytime to grab some Brooklyn Cider House hard cider to go. Mix & Match! SOLSTICE *LIMITED RELEASE 8/22 Wild fermented & dry, lychee, pineapple, lemon zest SINGLE BOTTLE 3-PACK CASE OF 12 6% abv MO *LIMITED RELEASE 8 MAIN LINE CIDERS 10 29 108 Still, racy, notes of citrus fruit & mineral. Drinks like a dry white wine BONE DRY 14 39 144 7% abv STILL BONE DRY *LIMITED RELEASE 8/22 SOLSTICE 14 39 144 Super dry, still, unfiltered (natural cider). Zesty and racy. STILL BONE DRY 14 39 144 6.8% abv THREE 3 OZ POUR FLIGHTS 11 off-dry: Half Sour, Rosé, Kinda Dry dry: Bone Dry, Mo, Raw, build your own: choose any three house ciders OTHER CIDER SOUTH HILL "POMM SUR LIE" 8 KITE & STRING - NORTHERN SPY 29 Still, Dry, barrel aged, tannic, acidic, apple skin, roasted nuts Semi-dry. -

(GISD) 2021. Species Profile Rosa Multiflora. Available From

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Rosa multiflora Rosa multiflora System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Rosales Rosaceae Common name baby rose (English), Japanese rose (English), multiflora rose (English), seven-sisters rose (English) Synonym Rosa cathayensis , (Rehd. & Wilson) Bailey Similar species Summary Rosa multiflora is a perennial shrub that forms dense, impenetrable thickets of vegetation . It colonises roadsides, old fields, pastures, prairies, savannas, open woodlands and forest edges and may also invade dense forests where disturbance provides canopy gaps. It reproduces by seed and by forming new plants that root from the tips of arching canes that contact the ground. Rosa multiflora is tolerant of a wide range of soil and environmental conditions and is thought to be limited by intolerance to extreme cold temperatures. Many species of birds and mammals feed on the hips of Rosa multiflora; dispersing the seeds widely. R. multiflora can colonise gaps in late-successional forests, even though these forests are thought to be relatively resistant to invasion by non-native species. It invades pasture areas, degrades forage quality, reduces grazing area and agricultural productivity and can cause severe eye and skin irritation in cattle. There are many strategies available to manage and control R. multiflora involving physical, chemical and biological means. view this species on IUCN Red List Species Description Munger (2002) states that R. multiflora \"bushes grow to a height of 1.8 to 3 metres and occasionally 4.6m. Stems (canes) are few to many, originating from the base, much branched, and erect and arching to more or less trailing or sprawling.