Table of Contents I. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Celebration of Our History and Heritage Dromboughil Community Association 1999-2019 a Celebration of Our History and Heritage

DROMBOUGHIL COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION 1999-2019 A CELEBRATION OF OUR HISTORY AND HERITAGE DROMBOUGHIL COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION 1999-2019 A CELEBRATION OF OUR HISTORY AND HERITAGE © 2019 Dromboughil Community Association and Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council Museum Services. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission of Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council Museum Services. ISBN 978-1-9161494-4-1 The publication of this book has been funded under the PEACE IV Understanding Our Area project. A project supported by the European Union’s PEACE IV Programme, managed by the Special EU Programmes Body (SEUPB). DROMBOUGHIL COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION 1999-2019 A CELEBRATION OF OUR HISTORY AND HERITAGE FOREWORD Community is at the centre of any society and this publication, with the memories of community members of ‘by-gone days’, reminds us that this has always been the case. Dromboughil Community Association 1999- 2019: A Celebration of our History and Heritage preserves some of the history of Dromboughil, offering the reader an opportunity to learn a bit about the area. This is important as we should all know how the places we live have been shaped and formed; bearing in mind our past makes us what we are today and shapes our future. Dromboughil Community Association celebrates its twentieth anniversary this year and I wish to take this opportunity to thank the members for all the work they have done over the years to strengthen, develop and build good relations between and among all sections of the local community. Their dedication and hard-work is a credit to them and this publication also gives a brief insight into what they offer the local community. -

– Report of the Executive Council Biennial Delegate Conference

Report of the Executive Council Biennial delegate conference 7 Tralee – 10 July, 200910 July, 32 Parnell Square, Carlin House, Dublin 1 4-6 Donegall Street Place, T +353 1 8897777 Belfast BT1 2FN Report of the F +353 1 8872012 T +02890 247940 F +02890 246898 Executive Council Biennial delegate conference [email protected] [email protected] www.ictu.oe www.ictuni.org Tralee 7–10 July, 2009 Overview by David Begg 07 Section One – The Economy 11 Chapter One – The Free Market Illusion 12 Chapter Two – Did Unions Cause the Recession? 16 Chapter Three – Low Standards in High Places 19 Chapter Four – Setting the Record Straight 22 Chapter Five – The All Island Economy 26 Section Two – Society 31 Chapter One – The Jobs’ Crisis 32 Chapter Two – Social Infrastructure 43 Section Three – Partnership, Pay & the Workplace 49 Chapter One – Partnership, Pensions and Repossessions 50 Chapter Two – Flexible Working and Equal Treatment 56 Chapter Three – Employment Permits and Regularisation 60 Chapter Four – Employment Law (the European Dimension) 64 Chapter Five – Employment Law (the Irish Dimension) 69 Section Four – Congress Organisation 73 Chapter One – Finance and Congress Committees 74 Chapter Two – Congress Networks 82 Chapter Three – Private and Public Sector Committees 86 Chapter Four – Building Union Organisation 97 Chapter Five – Congress Education & Training 102 Chapter Six – Communications & Campaigning 108 Section Five – Northern Ireland 115 Chapter One – Investing in Peace 116 Chapter Two – The work of NIC-ICTU 121 Chapter Three – Education, Skills & Solidarity 125 Section Six – Europe & the Wider World 131 Section Seven – Appendices 143 Executive Council 2007-2009 1 Patricia McKeown 9 Eamon Devoy UNISON (President) TEEU 2 Patricia King 10 Pamela Dooley SIPTU (Vice President) UNISON 3 Jack O’Connor 11 Seamus Dooley SIPTU (Vice President) NUJ 4 Joe O’Flynn 12. -

The Workers' Party in the Oail

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Materials Workers' Party of Ireland 1987 Ard Fheis Annual Delegate Conference - 1987 : General Secretary's Report Workers' Party of Ireland Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/workerpmat Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Workers' Party of Ireland, "Ard Fheis Annual Delegate Conference - 1987 : General Secretary's Report" (1987). Materials. 24. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/workerpmat/24 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Workers' Party of Ireland at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Materials by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License General Secretary's Report INTRODUCTION Few would now deny that the Workers' Party has established itself as the party of the Irish working class, particularly coming after the results of the recent general election in the Republic and the steady growth and activity of the Party in Northern Ireland. We have demonstrated over the past years in very practical and positive ways what the Workers' Party stands for. In and out of Parliament we have consistently upheld the interests of the working class. The struggle to build and expand the Workers' Party is not an easy one. We need only look back over the past fifteen or so years to see the progress we have made. In the February election of 1973 we put forward 10 candidates and received a total of 15,000 votes. -

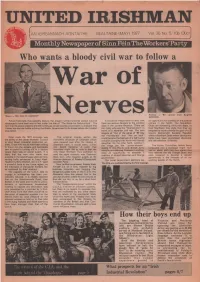

U N I T E D I R I S H M

UNITED IRISHMAN AN tElREANNACH AONTA BEALTAINE (MAY) 1977 Vol. 35 No. 5. lOp (30c) Monthly Newspaper of Sinn Fein The Workers'Party Who wants a bloody civil war to follow a War of Paisley — We cannot trust English Mason — Who does he represent? Nerves politicians. Future historians may possibly declare the present United Unionist Action Council It would be irresponsible to deny that an opportunity for a testing of the political stoppage to have been won or lost under the title of "The Battle for Ballylumford". The there are serious dangers to the working climate in the North. The Republican fact that the power stations are still running as we go to press would seem to Indicate that class in the current situation. There are Clubs are contesting thirty-two seats. In Paisley has lost the battle to bring the British Government to its knees before the Loyalist too many who see the "final solution" in their Manifesto they state that they are population. terms of a sectarian civil war. The twin prepared to work towards the goal of a 32 slogans of "Out of the ashes of '69 rose County Democratic Socialist Republic the Provisionals" and "Not an Inch" within a Northern State where democratic What made the 1974 stoppage was The original cracks within the could become the banners of a right-wing rights have been guaranteed absolutely the ability of the Ulster Workers' Council monolithic structure of Unionism which collusion plunging the North into bloody and sectarianism outlawed. to shut down industrial production en• were papered over after the closing of slaughter. -

Tony Heffernan Papers P180 Ucd Archives

TONY HEFFERNAN PAPERS P180 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2013 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Administrative History iv Archival History v CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content vi System of Arrangement viii CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access x Language x Finding Aid x DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note x ALLIED MATERIALS Published Material x iii CONTEXT Administrative History The Tony Heffernan Papers represent his long association with the Workers’ Party, from his appointment as the party’s press officer in July 1982 to his appointment as Assistant Government Press Secretary, as the Democratic Left nominee in the Rainbow Coalition government between 1994 and 1997. The papers provide a significant source for the history of the development of the party and its policies through the comprehensive series of press statements issued over many years. In January 1977 during the annual Sinn Féin Árd Fheis members voted for a name change and the party became known as Sinn Féin the Workers’ Party. A concerted effort was made in the late 1970s to increase the profile and political representation of the party. In 1979 Tomás MacGiolla won a seat in Ballyfermot in the local elections in Dublin. Two years later in 1981 the party saw its first success at national level with the election of Joe Sherlock in Cork East as the party’s first TD. In 1982 Sherlock, Paddy Gallagher and Proinsias de Rossa all won seats in the general election. In 1981 the Árd Fheis voted in favour of another name change to the Workers’ Party. -

UK UNIONIST PARTY - Alan Field 4 Silverbirch Avenue, Bangor BT19 6EJ ROBERT MCCARTNEY Maureen Ann Mccartney St

Supplement to THE BELFAST GAZETTE 10 MAY 1996 455 Party Name Name of Candidate Address of Candidate UK UNIONIST PARTY - Alan Field 4 Silverbirch Avenue, Bangor BT19 6EJ ROBERT MCCARTNEY Maureen Ann McCartney St. Catherines, 2 Circular Road East, Cultra, Holy wood BT18 OH A ULSTER INDEPENDENCE Gavin James Boyd 77 Brandon Parade, Connsbrook Avenue, Belfast MOVEMENT BT4 1JH Mark Ashley Black 32 Glenwood Park, Conway, Dunmurry BT17 David McClinton 16 Gardiner Street, Belfast BT13 2GT ULSTER UNIONIST PARTY Reg Empey Knockvale House, 205 Sandown Road, Belfast (UUP) BT5 6GX Jim Rogers 33 Princess Park, Holywood BT18 OPP Ian Adamson Marino Villa, 5 Marino Park, Holywood BT18 OAN Alan Crowe 60 Kings Road, Belfast BT5 6JL WORKERS PARTY Joe Bell 80 Mountpottinger Road, Belfast Marie Mooney 4 Bryson Gardens, Belfast BELFAST NORTH Party Name Name of Candidate Address of Candidate ALLIANCE PARTY Nicholas Whyte 32 Serpentine Parade, Newtownabbey Tommy Frazer 3 Ravelston Avenue, Newtownabbey Lindsay Whitcroft 9 Oakvale Avenue, Newry DEMOCRATIC LEFT Seamus Lynch 30 Floral Gardens, Glengormley BT36 7SE John McLaughlin 18 Oceanic Avenue, Belfast DEMOCRATIC UNIONIST Nigel Alexander Dodds 20 Castle Lodge, Banbridge (DUP) - IAN PAISLEY William John Snoddy 34 Carnbue Avenue, Glengormley David Smylie 805 Crumlin Road, Belfast William Henry De Courcy 10 Linford Green, Rathcoole, Newtownabbey GREEN PARTY Peter Emerson Rhubarb Cottage, 36 Ballysillan Road, Belfast BT14 7QQ Rosemary Elizabeth Warren 24 Glenburn Park, Belfast BT14 3TF INDEPENDENT CHAMBERS Joseph Addis Coggle 31 Berlin Street, Belfast Sally Irvine 41 Mayo Street, Belfast INDEPENDENT McMULLAN Wesley H. Holmes 7 Slievedarragh Park, Belfast BT14 8JA Helen Christine Craig 9 Princess Park, Holywood, Co. -

General Secretary's Report to the Workers' Party Ard Fheis, Annual Delegate Conference 1988

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Materials Workers' Party of Ireland 1988 General Secretary's Report to the Workers' Party Ard Fheis, Annual Delegate Conference 1988 Workers' Party of Ireland Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/workerpmat Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Workers' Party of Ireland, "General Secretary's Report to the Workers' Party Ard Fheis, Annual Delegate Conference 1988" (1988). Materials. 14. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/workerpmat/14 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Workers' Party of Ireland at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Materials by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License THE ~WORKERS PARTY PEACE WORK DEMOCRACY CLASS POLITICS General Secretary's Report Ard Fheis/ Annual Delegate Conference 1988 Contents Introduction 3 Central Executive Committee 4 The Workers' Party in the Dail 6 Environment & Local Government 8 Finance Committee 10 Health & Social Services 12 Cultural Committee 13 National Women's Committee 14 Justice & Civil Liberties 16 Economic Affairs Committee 18 Publicity & Communications 22 National Youth Committee 24 Northern Ireland 26 Education Committee 27 International Affairs 29 Electoral & Recruitment 32 Conclusion 35 Members of Ard Comhairle/CEC and members of EPC, EMC and Chairpersons of Specialist Committees The Ard Comhairle/ CEC met on four occasions, three of which were of two days duration. The following officers were elected by the CEC, Tomas Mac Giolla having been elected Party President at the Ard Fheis. -

Six Girls in Armagh Jail Lihood

DEMOCRAT FOUNDED IN 1939f THE PAPER THAT SHOWS THE WAY FORWARD No. 349 JULY 1973 7p NOW THEY ARE FISHERMEN HOLD DUBLIN CONFERENCE ISHERMEN from all parts of the F country met in Dublin in May 10 organise against the E.E.C. hreat to their livelihood. The secre- tary of the National Fishermen's Defence Association, Mr Jimmy 0 Conor, said that the meeting in- dicated the beginning of an aware- ness among Irish fishermen of the »ery real danger to our fishing waters caused by E.E.C. member ship. A message of solidarity was sent 10 the Icelandic fishermen engaged n the so-called "Cod War" on be- half of their stand for a 50-mile INFLATION limit to protect theirsource of live- Six girls in Armagh Jail lihood. The message stated that Irish fishermei of the EMPTIES ALL 'act that the le were H E infamies of the Heath Government in the six counties have totally depen Ns in" iustry for nd we T seemingly no end. OUR POCKETS wish to expi it «n# They have six young Irish wash for several days, and Margaret Shannon's. When she - BUT NOT THEIRS sledge our si in their women incarcerated in Armagh Stowed her hideous photographs heard the fracas she tried to reach spirited efforts their Jail without any charge o* thft of young |$ft whose bodies the other girl, bujt was seized, her main national THE rate of inflation which is were horribly ntlrtilated, imply- head banged on the wall, and • the greatest in Europe is to be The message" a trial. -

Fianna Fail Cannot Deliver the Goods

UNITED IRISHMAN AN tElREANNACH AONTA UIL (JULY) 1977 Vol. 35 No. 7. lOp (30c) Monthly Newspaper of Sinn Fein The Workers' Party A new generatioFiannn of voters made itsa difficulFait task inl re-establishin cannog itself as tessentiall delivey this is all Brownre cathn offere, whicgoodh for workerss woul d mean a return voice heard loud and clear on June a party of the working-class. The party Workers will also be looking for To the 'guaranteed Irish' hardship of 16th last. In throwing out the which failed to add even a social- something more than a sudden fit of the Thirties. 'Government of all the talents' hun• democratic flavour to the Coalition socialist fervour from Labour leaders. So, while the 'nationally-minded' dreds of thousands of young voters Government will be hard pushed to Already the unseemly scramble to the Provisionals and IRSP celebrate the showed they wanted jobs not excuses. convince workers that its' 'soul' is 'Left' has begun as the O'Learys and victory of Fianna Fail, the organised And they will be just as decisive in socialist. The debonair Michael Halligans brush up their old working-class must prepare for victory telling Fianna Fail that promises must O'Leary may cut a fine figure as a socialist speeches. But it will not go in the years ahead. The response to be kept. socialist in the rarefied environs of unnoticed that the Labour Party is socialist policies in this election was This worries Jack Lynch. Fianna Grafton Street but it won't wash with 'socialist' only when in opposition. -

Putting Up, and Taking Down, the Barricades

Reflections on 1969 Lived Experiences & Living History (Discussion 2) Putting up, and taking down, the barricades compiled by Michael Hall ISLAND 119 PAMPHLETS 1 Published December 2019 by Island Publications 132 Serpentine Road, Newtownabbey BT36 7JQ © Michael Hall 2019 [email protected] http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/islandpublications The Fellowship of Messines Association gratefully acknowledge the assistance they have received from their supporting organisations. Printed by Regency Press, Belfast 2 Introduction The Fellowship of Messines Association was formed in May 2002 by a diverse group of individuals from Loyalist, Republican and other backgrounds, united in their realisation of the need to confront sectarianism in our society as a necessary means of realistic peace-building. The project also engages young people and new citizens on themes of citizenship and cultural and political identity. Among the different programmes initiated by the Messines Project was a series of discussions entitled Reflections on 1969: Lived Experiences & Living History. These discussions were viewed as an opportunity for people to engage positively and constructively with each other in assisting the long overdue and necessary process of separating actual history from some of the myths that have proliferated in communities over the years. It was felt important that current and future generations should hear, and have access to, the testimonies and the reflections of former protagonists while these opportunities still exist. Access to such evidence would hopefully enable younger generations to evaluate for themselves the factuality of events, as opposed to some of the folklore that passes for history in contemporary society. The subject of this publication is the second discussion – out of a planned series of six – which was held in the Irish Congress of Trade Unions premises in Donegall Street, Belfast, on 21 September 2019. -

Gerry Adams and the Modernisation of Republicanism

Conflict Quarterly Gerry Adams and the Modernisation of Republicanism by Henry Patterson INTRODUCTION: AN OVERVIEW OF PROVO MODERNISATION Twenty years after its formation in 1970 the Provisional IRA is arguably the most formidable terrorist group in the world. Its active service units are able to strike regularly on the British mainland and against British military personnel in Europe as well as in the streets and country lanes of Northern Ireland. It has a daunting arsenal of weaponry and Semtex explosive given it by Libya in 1985- 1986 and, although the security forces in the Irish Republic have uncovered some of this material, it is reckoned that the IRA has enough hardware to sustain it to the end of this decade. Yet all is not well with the Provisionals. Their supporters are increasingly war-weary and the wild optimism of the early 1980s has given way to circumstances where leading republicans can openly contem plate defeat. This essay will attempt to locate the present problems of the Provisional movement within the new strategic perspective developed by a group of Belfast republicans in the mid-1970s. The key figure in this group was Gerry Adams and by an examination of Adam's project it hopes to throw light on the present dilemmas of Irish republicanism. Gerry Adams, current president of Sinn Fein and since 1983 MP for West Belfast, is recognized as the central figure in the development of the strategy of the Provisional republican movement since the mid-1970s. ' He was associated with an increasing emphasis on the need to "broaden the battlefield" from the almost pure militarism of the early Provisionals to incorporate a new active role for the political wing of the movement, Sinn Fein. -

Ballymurphy News : May Day Call

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Materials Workers' Party of Ireland 1975 Ballymurphy News : May Day Call Republican Clubs Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/workerpmat Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Republican Clubs, "Ballymurphy News : May Day Call" (1975). Materials. 49. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/workerpmat/49 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Workers' Party of Ireland at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Materials by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Organ of ORR--GRAY Rep.qub ClARKE--lARKIN Rep.Club~ CASEMENT Rep. Club TRACEY Rep. CliJb '. THE SOCIALIST REPUBLIC Ol"e 11 .a Cia-·c:e e""""c:_.'.. Volunleer Paul Crawford Wp,comrades,are in a morf' dangf'r ou~ pf'riod today thaIl ;;.t. any other HmI-' in the past six years, but we have not built our prganisation frozn Cork to Belfast,frozn Newry to Galway,to perznit its destruction by a handful of ultra-left terrorists. We have ouUined the yath to revolut ionary victorY'P'3.ul Crawford was playing his role in that struggle:fore most in Housing A ction in his area, he died because he was engaged in one of the zno st impo rtant diznensions in revolutionary activity--education, bringing the Republican understanding and solution to the people. Paul Crawford died for a Deznocratic Socialist Republic.