Affected Environment Chapter 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Block Island Sound Rhode Island Sound Inner Continental Shelf

Ecology of the Ocean Special Area Management Plan Area: Block Island Sound Rhode Island Sound Inner Continental Shelf Alan Desbonnet Carrie Byron with help from Elise Desbonnet, Barry Costa-Pierce, Meredith Haas and the PELL LIBRARY STAFF and MANY, MANY Researchers The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf GEOLOGY 2,500 km2 31 m average 60 m max 1,350 km2 40 m averageAcadian vs. Virginian 100 m maxecoregions The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf Boothroyd 2008 SLR 2.5-3.0 mm per year (1/10th inch) Glacial Origins--- a key element E. Uchupi, N.W. Driscoll, R.D. Ballard, and S.T. Bolmer, 2000 The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf Boothroyd 2009 Downwelling – Combined Flow Circulation/currents shaped by the geology Bottom habitats are dynamic/ever changing The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf Boothroyd 2008 Winter = NW (stronger) Summer = SW (milder) WINDS NOT a major driver of circulation Av.Big Wave implications height for stratification = 1-3 m Max = 7 m (9 m 100 yr. wave) The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf Spaulding 2007 Most recent Cat3 = Esther in 1961 Most recent = Bob (Cat2) in 1991 No named hurricane 18 years 17 RI hurricanes: 7 Category 1 8 Category 2 2 Category 3 The Ecology of Rhode Island Sound, Block Island Sound and the Inner Continental Shelf NOAA Hurricane Center online data 2010 Important -

RI State Pilotage Commission Rules and Regulations

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS STATE PILOTAGE COMMISSION RULES AND REGULATIONS State Pilotage Commission C/o Division of Law Enforcement 235 Promenade Street Providence, RI 02908 Telephone (401) 222-3070 Fax (401) 222-6823 Commission Members: Capt. E. Howard McVay, Jr., Chairman Larry Mouradjian, Member Steven Hall., Member Capt. J. Peter Fritz, Member Ms. Joanne Scorpio, Secretary Gary E. Powers, Esq., Legal Counsel 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description of Pilotage Commission and Members RULE 1 ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURES ACT42-35 AS AMENDED RULE 2 ORGANIZATIONS AND METHOD OF OPERATIONS RULE 3 PRACTICE BEFORE THE COMMISSION RULE 4 PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS RULE 5 HEARINGS RULE 6 PETITIONS FOR RULE MAKING, AMENDMENT OR REPEAL RULE 7 DECLARATORY RULINGS RULE 8 PUBLIC INFORMATION RULE 9 APPRENTICE PILOT PROGRAM FOR BLOCK ISLAND SOUND RULE 10 APPRENTICE PILOT PROGRAM FOR NARRAGANSETT BAY RULE 11 CLASSIFICATION OF BLOCK ISLAND PILOTS RULE 12 CLASSIFICATION OF RHODE ISLAND PILOTS FOR WATERSNORTH OF LINE FROM POINT JUDITH TO SAKONNET POINT RULE 13 PILOTAGE SYSTEM FOR THE WATERS OF NARRAGANSETT BAY AND ITS TRIBUTARIES RULE 14 PILOT BOATS RULE 15 PILOTS RULE 16 RATES OF PILOTAGE FEES, WHICH SHALL BE PAID TO STATE LICENSED PILOTS IN BLOCK ISLAND SOUND RHODE ISLAND STATE PILOTAGE COMMISSION The State Pilotage Commission consists of four (4) members appointed by the Governor for a term of three (3) years one of whom shall be the Associate Director of the Bureau of Natural Resources of the Department of Environmental Management, ex officio; one shall be the Director of the Department of Environmental Management, ex officio; one shall be a State Licensed Pilot with five (5) years of active service on the waters of this State; and one shall represent the public. -

RI DEM/Water Resources

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS July 2006 AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted in accordance with Chapter 42-35 pursuant to Chapters 46-12 and 42-17.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws of 1956, as amended STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS RULE 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................ 1 RULE 2. LEGAL AUTHORITY ........................................................................................ 1 RULE 3. SUPERSEDED RULES ...................................................................................... 1 RULE 4. LIBERAL APPLICATION ................................................................................. 1 RULE 5. SEVERABILITY................................................................................................. 1 RULE 6. APPLICATION OF THESE REGULATIONS .................................................. 2 RULE 7. DEFINITIONS....................................................................................................... 2 RULE 8. SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS............................................... 10 RULE 9. EFFECT OF ACTIVITIES ON WATER QUALITY STANDARDS .............. 23 RULE 10. PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING ADDITIONAL REQUIREMENTS FOR EFFLUENT LIMITATIONS, TREATMENT AND PRETREATMENT........... 24 RULE 11. PROHIBITED -

Coastal Lakes

A publication of the North American Lake Management Society LAKELINEVolume 33, No. 4 • Winter 2013 Coastal Lakes Permit No. 171 No. Permit Bloomington, IN Bloomington, 47405-1701 IN Bloomington, PAID 1315 E. Tenth Street Tenth E. 1315 US POSTAGE US MANAGEMENT SOCIETY MANAGEMENT NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT NORTH AMERICAN LAKE AMERICAN NORTH Winter 2013 / LAKELINE 1 2 Winter 2013 / LAKELINE AKE INE Contents L L Published quarterly by the North American Lake Management Society (NALMS) as a medium for exchange and communication among all those Volume 33, No. 4 / Winter 2013 interested in lake management. Points of view expressed and products advertised herein do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of NALMS or its Affiliates. Mention of trade names and commercial products shall not constitute 4 From the Editor an endorsement of their use. All rights reserved. Standard postage is paid at Bloomington, IN and 5 From the President additional mailing offices. 2013 NALMS Symposium Highlights NALMS Officers 6 President 12 2013 NALMS Awards Terry McNabb 17 2013 NALMS Photo Contest Winnters Immediate Past-President Ann Shortelle 2013 NALMS Election Results 18 President-Elect Reed Green Secretary Coastal Lakes Sara Peel Fresh, Salt, or Brackish: Managing Water Quality in a Treasurer 20 Michael Perry Coastal Massachusetts Pond NALMS Regional Directors 23 The Coastal Lagoons of Southern Rhode Island Region 1 Wendy Gendron Region 2 Chris Mikolajczyk Region 3 Imad Hannoun 28 Climatic Influence on the Hydrology of Florida’s Coastal Region 4 [vacant] Region 5 Melissa Clark Dune Lakes Region 6 Julie Chambers Region 7 Jennifer Graham 32 Tenmile Lake: Life and Limnology on the Oregon Coast Region 8 Craig Wolf Region 9 Todd Tietjen 36 Cleawox Lake, Oregon: The Coastal Sands of Cultural Region 10 Frank Wilhelm Region 11 Anna DeSellas Omission Region 12 Ron Zurawell At-Large Jason Yarbrough 45 Nitinat Lake – A British Columbia Tidal Lake Student At-Large Lindsey Witthaus LakeLine Staff Editor: William W. -

2021 Connecticut Boater's Guide Rules and Resources

2021 Connecticut Boater's Guide Rules and Resources In The Spotlight Updated Launch & Pumpout Directories CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION HTTPS://PORTAL.CT.GOV/DEEP/BOATING/BOATING-AND-PADDLING YOUR FULL SERVICE YACHTING DESTINATION No Bridges, Direct Access New State of the Art Concrete Floating Fuel Dock Offering Diesel/Gas to Long Island Sound Docks for Vessels up to 250’ www.bridgeportharbormarina.com | 203-330-8787 BRIDGEPORT BOATWORKS 200 Ton Full Service Boatyard: Travel Lift Repair, Refit, Refurbish www.bridgeportboatworks.com | 860-536-9651 BOCA OYSTER BAR Stunning Water Views Professional Lunch & New England Fare 2 Courses - $14 www.bocaoysterbar.com | 203-612-4848 NOW OPEN 10 E Main Street - 1st Floor • Bridgeport CT 06608 [email protected] • 203-330-8787 • VHF CH 09 2 2021 Connecticut BOATERS GUIDE We Take Nervous Out of Breakdowns $159* for Unlimited Towing...JOIN TODAY! With an Unlimited Towing Membership, breakdowns, running out GET THE APP IT’S THE of fuel and soft ungroundings don’t have to be so stressful. For a FASTEST WAY TO GET A TOW year of worry-free boating, make TowBoatU.S. your backup plan. BoatUS.com/Towing or800-395-2628 *One year Saltwater Membership pricing. Details of services provided can be found online at BoatUS.com/Agree. TowBoatU.S. is not a rescue service. In an emergency situation, you must contact the Coast Guard or a government agency immediately. 2021 Connecticut BOATER’S GUIDE 2021 Connecticut A digest of boating laws and regulations Boater's Guide Department of Energy & Environmental Protection Rules and Resources State of Connecticut Boating Division Ned Lamont, Governor Peter B. -

CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: Washington County, RI 71.251684W

41.669103N 41.670104N 72.038382W 2010 CENSUS - CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: Washington County, RI 71.251684W West Warwick Greenwich Bay 3 LEGEND v 2 i town 78440 0 5 R 0 Coventry town 18640 401 0 g 0 i Warwick° T T B N R 136 Mount Hope Bay SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE E 74300 O 401 K Bristol P omut B otow Riv N Federal American Indian P W R towomut R E town 09280 o iv E I L'ANSE RES 1880 P W S Bristol Hbr Reservation N T P O S nt Rd c O Poi h L o Off-Reservation Trust Land, c o ja l R o h 0 P o T1880 u T 0 s 1 Hawaiian Home Land Fo e 0 rg R e d Rd 05 Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area, 114 Alaska Native Village Statistical Area, KAW OTSA 5340 102 East Greenwich Tribal Designated Statistical Area town 22240 501.04 State American Indian arbro d Bri ok R West Greenwich town 77720 r Tama Res 4125 KENT 003 402 e Reservation 1 Dr h Essex Rd tc le F 403 Sanford Rd State Designated Tribal 403 Post Rd t er Rd S Perimet Lumbee STSA 9815 ol Statistical Area 4 o Potter h Dr Sc Dahlia Rd Rte 6 4 Rd Rte 6 1 le Alaska Native Regional Davisvillesvil Construction Battalion Ctr avi Rd Portsmouth town 57880 NANA ANRC 52120 2 D Jones Corporation Narragansett Bay 24 24 State (or statistically 403 403 NEW YORK 36 Beach Pond KENT 003 Roger equivalent entity) 102 D N 501.03 State Park e a A Ln H r la i o r n d r o p p o r o 9 w R C 0 e a 102 Fa k INGTON 0 mp C r l ASH t allahan Rd i W k t c n on L Dr s County (or statistically s a Seaview S R n o i u t C dg H Ave Belver B e ny Ln P ERIE 029 o Q P d a i t r la R Dr ll S Ave equivalent entity) o in m A 501.02 -

Field Guide to Coastal Environmental Geology of Rhode Island's Barrier Beach Coastline

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository New England Intercollegiate Geological NEIGC Trips Excursion Collection 1-1-1981 Field Guide to Coastal Environmental Geology of Rhode Island's Barrier Beach Coastline Fisher, John J. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips Recommended Citation Fisher, John J., "Field Guide to Coastal Environmental Geology of Rhode Island's Barrier Beach Coastline" (1981). NEIGC Trips. 297. https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips/297 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the New England Intercollegiate Geological Excursion Collection at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NEIGC Trips by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 153 Trip B-6 Field Guide to Coastal Environmental Geology of Rhode Island's Barrier Beach Coastline fcy John J. Fisher Department of Geology University of Rhode Island Kingston, RI 02881 Introduction The Rhode Island southern coastline, 30 km in length, can he classified as a barrier beach complex shoreline. Developed from a mainland consisting pri marily of a glacial outwash plain, it has been submerged by recent sea level rise. Headlands (locally called "points") composed of till and outwash plain deposits separate a series of lagoon-like hays (locally called "ponds") that are drowned glacial outwash channels. Interconnecting baymouth harriers (locally called "harrier "beaches") with several inlets make up the major shoreform of this coast (Figure l). This field guide is an introduction to the coastal environmental geology features of the Rhode Island harrier beach coast. -

Town of Westerly Harbor Management Plan 2016 Revised 10/28/19

Town of Westerly Harbor Management Plan 2016 Revised 10/28/19 As Adopted by the Westerly Town Council, October 28, 2019 1 Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 3 WESTERLY HMC MISSION STATEMENT ................................................................... 4 PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION .............................................................................................. 5 HISTORY ......................................................................................................................... 18 WATER QUALITY.......................................................................................................... 20 NATURAL RESOURCES ............................................................................................... 30 THE BEACHES................................................................................................................ 36 SHORELINE PUBLIC ACCESS ................................................................................... 41 HARBOR FACILITIES AND BOAT RAMPS ............................................................... 53 MOORING MANAGEMENT.......................................................................................... 60 STORM PREPAREDNESS.............................................................................................. 75 WESTERLY HARBOR MANAGEMENT PLAN-ORDINANCE ................................. 81 2 INTRODUCTION The Westerly Harbor Plan is formulated in order to -

Chapter 7: Marine Transportation, Navigation, and Infrastructure

Ocean Special Area Management Plan Chapter 7: Marine Transportation, Navigation, and Infrastructure Table of Contents List of Figures.............................................................................................................................. 3 List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... 4 700 Introduction.......................................................................................................................... 5 710 History of Marine Transportation in the Ocean SAMP Area ......................................... 7 720 Navigation Features in the Ocean SAMP Area............................................................... 11 720.1 Area Overview..................................................................................................... 11 720.2 Shipping Lanes, Traffic Separation Schemes, and Precautionary Areas...... 13 720.3 Recommended Vessel Routes............................................................................. 14 720.4 Ferry Routes........................................................................................................ 14 720.5 Pilot Boarding Areas........................................................................................... 14 720.6 Anchorages .......................................................................................................... 15 720.7 Navy Restricted Areas ....................................................................................... -

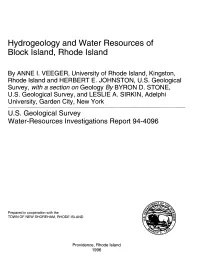

Hydrogeology and Water Resources of Block Island, Rhode Island

Hydrogeology and Water Resources of Block Island, Rhode Island By ANNE I. VEEGER, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, Rhode Island and HERBERT E. JOHNSTON, U.S. Geological Survey, with a section on Geology By BYRON D. STONE, U.S. Geological Survey, and LESLIE A. SIRKIN, Adelphi University, Garden City, New York U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 94-4096 Prepared in cooperation with the TOWN OF NEW SHOREHAM, RHODE ISLAND Providence, Rhode Island 1996 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GORDON P. EATON, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: Subdistrict Chief U.S. Geological Survey Massachusetts - Rhode Island District Earth Science Information Center U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports Section Water Resources Division Box 25286, MS 517 275 Promenade Street, Suite 150 Denver Federal Center Providence, Rl 02908 Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Abstract.............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction.......................................................^^ 2 Purpose and Scope.................................................................................................................................................. 2 Previous Investigations.......................................................................................................................................... -

The Sounds Conservancy

QUEBEC-LABRADOR FOUNDATION Atlantic Center for the Environment 1995-2014 The Sounds Conservancy . QLF MISSION STATEMENT QLF exists to promote global leadership development, to support the rural communities and environment of eastern Canada and New England, and to create models for stewardship of natural resources and cultural heritage that can be shared worldwide. QUEBEC-LABRADOR FOUNDATION TABLE OF CONTENTS The Ven. Robert A. BrYan Letter From The President . 2 Founding Chairman LaWrence B. Morris Acknowledgements . 3 President The Sounds Conservancy . 4 EliZabeth Alling Executive Vice President The Quebec-Labrador Foundation . 5 Managing Editor Rivers and Watersheds . 7 HenrY Hatch Charles Hildt Bays and Estuaries . 17 Grace Weatherall Writers Coastal Marshes . 33 Adrianne Brand Constance de BrUn Intertidal Zone . 45 Writers Sounds Conservancy Publication (2000) Subtidal Zone . 51 Agnes Simon Education . 61 Editor Species Conservation . 77 Christopher O’Book KeVin Porter Marine Legislation . 97 Photography Editors QUebec-Labrador FoUndation Appendix– Atlantic Center for the EnVironment 55 SoUth Main Street Grantees Listed by Sound . 104 IpsWich, MassachUsetts 01938 Grantees Listed by Subject . 115 Phone 978.356.0038 FaX 978.356.7322 Grantees Listed by Year . 129 ......... 1 Index . 146 QLF Canada 606, rUe Cathcart Glossary of Terminology . 159 BUreaU 430 Montréal, QUébec H3B 1K9 References: Photography and Illustration . 163 Canada Phone 514.395.6020 Cover Photograph: Looking toward Rhode Island Sound from the Aquinnah FaX 514.395.4505 Cliffs at the western end of Vineyard Sound, Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts WWW.QLF.org Photograph bY Candace Cochrane ......... Inside Cover Photograph: Boardwalks along the coast preserve ecosystems and make the Sounds accessible to the public. -

10. Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of Narragansett Bay, Block Island

Ocean Special Area Management Plan 10. Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of Narragansett Bay, Block Island Sound, Rhode Island Sound, and Nearby Waters: An Analysis of Existing Data for the Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan by Robert D. Kenney and Kathleen J. Vigness-Raposa University of Rhode Island, June 22, 2010 June 22, 2010 Technical Report #10 Page 1 of 337 Ocean Special Area Management Plan Executive Summary All available sources of information on the occurrence of marine mammals and sea turtles in the waters of the Rhode Island study area—encompassing Narragansett Bay, Block Island Sound, Rhode Island Sound, and nearby coastal and continental shelf areas—were combined to assess the distribution and relative abundance of those species with respect to the Rhode Island Special Area Management Plan. Thirty-six species of marine mammals (30 cetaceans, 5 seals, 1 manatee) and four species of sea turtles are known to occur in the area. Sixteen were categorized as common to abundant (>100 total records from all sources combined), six as regular (10–100 records), and eighteen as rare to accidental (<10 records). Eleven of those species—six whales, the manatee, and four sea turtles—are listed as Endangered or Threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. One other species was present historically but is now extinct in the North Atlantic—the gray whale. Eight additional species, including one Endangered sea turtle, are considered to be hypothetical in the study area—with one or more records nearby. The forty marine mammal and sea turtle species that occur in the study area have been ranked into five levels of conservation priority relative to the SAMP, taking into account such factors as overall abundance of the population, abundance in the study area, likelihood of occurrence in the SAMP area, ESA-listing status, sensitivity to specific anthropogenic activities, and existence of other known threats to the population.