Pac Plan Review Rpt 2013 Vol 2 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 October 2008

Votes and Proceedings Of the Eighteenth Parliament No. 8 First Sitting of the Sixth Meeting 10.00 a.m. Thursday, 9th October 2008 1. The House met at 10 a.m. in accordance with the resolution of the House made on Friday, 5th September 2008. 2. Hon. Riddel Akua, M.P., Speaker of Parliament, took the Chair and read Prayers. 3. Statement from the Chair Hon. Riddel Akua, M.P., Speaker of Parliament, made a statement on House Matters which reads as follows:- ‘Honourable Members, I need to make a few remarks as follow-up to the statements I have made in previous sittings. Firstly, Ms. Katy LeRoy’s contract as Parliamentary Counsel has been signed and duly ratified by the House Committee. She will begin her duties on October 13, this year. Secondly, as Members would have noticed construction work is being carried out in the main Parliament building. Office configuration work is carried out where the Committee Room has been moved and will be situated on the top floor where the dining room is now. That floor will serve 3 purposes. It shall remain as a diner for Parliament dinner functions, the other two offices shall serve as committee rooms. When these offices are completed, committee work can run simultaneously depending on the need. What used to be the Committee and library rooms, upon completion will serve as offices for the Parliament Secretariat staff. The former library will hold the Hansard staff while the latter, the Committee room will hold the supporting staff. The PAC office is also reconfigured to staff the Chairman and his supporting staff. -

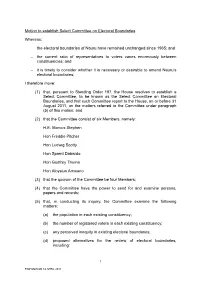

Whereas: Motion to Establish Select Committee on Electoral Boundaries – the Electoral Boundaries of Nauru Have Remained Uncha

Motion to establish Select Committee on Electoral Boundaries Whereas: – the electoral boundaries of Nauru have remained unchanged since 1965; and – the current ratio of representatives to voters varies enormously between constituencies; and – it is timely to consider whether it is necessary or desirable to amend Nauru’s electoral boundaries; I therefore move: (1) that, pursuant to Standing Order 197, the House resolves to establish a Select Committee, to be known as the Select Committee on Electoral Boundaries, and that such Committee report to the House, on or before 31 August 2011, on the matters referred to the Committee under paragraph (5) of this motion; and (2) that the Committee consist of six Members, namely: H.E. Marcus Stephen Hon Freddie Pitcher Hon Ludwig Scotty Hon Sprent Dabwido Hon Godfrey Thoma Hon Aloysius Amwano (3) that the quorum of the Committee be four Members; (4) that the Committee have the power to send for and examine persons, papers and records; (5) that, in conducting its inquiry, the Committee examine the following matters: (a) the population in each existing constituency; (b) the number of registered voters in each existing constituency; (c) any perceived inequity in existing electoral boundaries; (d) proposed alternatives for the review of electoral boundaries, including: 1 FWP MOTION 14 APRIL 2011 (i) the possibility of separating certain constituencies into separate constituencies for each district in order to create a more equitable and relevant division of electorates; (ii) the possibility in particular -

Political Reviews

Political Reviews michael lujan bevacqua, elizabeth (isa) ua ceallaigh bowman, zaldy dandan, monica c labriola, nic maclellan, tiara r na'puti, gonzaga puas peter clegg, lorenz gonschor, margaret mutu, salote talagi, forrest wade young 187 political reviews • micronesia 213 Nauru protest. Not surprisingly, a further focus of media criticism has been the Over the past two years, Nauru has Nauru government’s combative rela- raised its regional and international tions with overseas journalists and profile, as the government led by restrictions on access for many media President Baron Divavesi Waqa and organizations, including the Australian Minister for Finance and Justice David Broadcasting Corporation (abc). Adeang sought to address a range of The Micronesian nation of eleven economic, political, and social chal- thousand people faces many devel- lenges at home. opment challenges. A quarter of the In January 2018, Nauru celebrated population lives below the national its fiftieth anniversary of independence poverty line, according to data from as a sovereign nation. A key part of the Asian Development Bank (adb the anniversary year was hosting the 2018). forty-ninth Pacific Islands Forum in Education standards and truancy September. The government’s unity, continue to be major problems. In however, ended with national elections 2018, only 60 percent of students in August 2019, when Waqa lost his attended school for the midyear exam- seat in the Boe constituency, opening inations, and of these, less than half the way for a new era of governance. of the students in years 1–8 passed the Throughout 2018–2019, the Waqa examinations. Of year 8 students, only government was engaged in domestic 14 percent passed mathematics, 32 reforms, introducing new economic percent passed science, and 54 percent policies, major changes to superan- passed English (Nauru Bulletin 2018c, nuation, and fundamental reforms 7). -

Votes and Proceedings of the Twentieth Parliament No. 3 First Sitting of the Third Meeting Monday, 1 November 2010 10:00 A.M. 1

Votes and Proceedings Of the Twentieth Parliament No. 3 First Sitting of the Third Meeting Monday, 1st November 2010 10:00 a.m. 1. The House met at 10:00a.m pursuant to the advice given by His Excellency the President Hon. Marcus Stephen, M.P. 2. Hon. Landon Deireragea M.P (Deputy Speaker) took the Chair and read Prayers. 3. Election of Speaker The Deputy Speaker called for nominations for the Speakership. His Excellency the President, nominated Mr. Scotty (Anabar/Ijuw/Anibare) to be the Speaker of the House. Mr. Thoma (Aiwo) seconded the nomination. Mr. Scotty accepted his nomination. There being no other nominations forthcoming, Mr. Scotty was duly elected Speaker of the House. The mover and seconder of the motion escorted Mr. Scotty to the Chair. The Speaker made a short statement to the House and thanked Members for the honoured conferred upon him. 4. Election of President The Chair called for nominations for the election of President of the Republic of Nauru. Mr. Deireragea (Ewa/Anetan) nominated Mr. Stephen (Ewa/Anetan) to be President. Dr. Keke (Yaren) seconded. Mr. Stephen accepted his nomination. Mr. Thoma (Aiwo) nominated Mr. Dube (Aiwo) to be President. Mr. Waqa (Boe) seconded. 1 Mr. Dube accepted the nomination. There being no other nominations forthcoming, voting by secret ballot took place. Result: Mr. Stephen 11 votes Mr. Dube 6 votes Mr. Stephen was duly elected President of the Republic. At the request of the President and with the consent of the House, the Chair then suspended the sitting, to resume when the bell rings. -

Nauru Bulletin Issue 9-2016/141 29 July 2016 Nauru 2016 Elections Wrap Up

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Nauru Bulletin Issue 9-2016/141 29 July 2016 Nauru 2016 elections wrap up he Nauru General Elections on 9 Boe also lost their seats. Roland TJuly 2016 returned the majority of Kun did not contest these elections the sitting MPs with six new members therefore the second seat for Buada joining the parliament and making was won by new comer Jason their debut in the Twenty-Second Bingham Agir. This was Mr Agir’s Parliament. second effort at running in the Long serving member of parliament Elections for his constituency. Also and former president and speaker first time candidate Asterio Appi Ludwig Scotty lost his seat in his replaced Mr Batsiua in Boe. The two Constituency of Anabar/Ijuw/Anibare Menen seats were won by another as well as another former president second time candidate and former Marcus Stephen in the neighbouring secretary for justice Lionel Aingimea Constituency of Ewa/Anetan. and new candidate Vodrick Detsiogo. Mr Scotty was replaced by new comer Members for Aiwo, Ubenide and Jaden Dogireiy who stood for elections Yaren remain unchanged. a second time and Mr Stephen to first The numbers alongside each time candidate Sean Oppenheimer. candidate name in the following table Suspended MPs Squire Jeremiah and Polling station in Baitsi district indicate the points attained by each former president Sprent Dabwido both candidate. They do not represent the from Menen and Mathew Batsiua of number of individual votes. Cont pg 2... President Waqa announces cabinet ministers even of the eight constituencies cast their vote at the General SElections on 9 July except for Aiwo which had its polling postponed until Monday 11 July. -

Republic of Nauru

ASIA/PACIFIC GROUP ON MONEY LAUNDERING Nauru ME1 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism Republic of Nauru July 2012 Nauru is a member of the Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG). This evaluation was conducted by the APG and was adopted as a 1st mutual evaluation by its Plenary on 18 July 2012. 2012 ASIA/PACIFIC GROUP ON MONEY LAUNDERING. All rights reserved. No reproduction or translation of this publication may be made without prior written permission. Requests for permission to further disseminate, reproduce or translate all or part of this publication should be obtained from the APG Secretariat, Locked Bag A3000, Sydney South, NSW 1232, Australia. (Telephone: +612 9277 0600 Fax: +612 9277 0606 Email: [email protected]) 2 CONTENTS Page Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 7 1. GENERAL ..................................................................................................................................... 15 1.1. General information on Nauru ........................................................................................ 15 Structural elements -

By Paul D. Miller the NAURU ELEGIES the NAURU ELEGIES NAURU

THE NAURU ELEGIES By Paul D. Miller THE NAURU ELEGIES THE NAURU ELEGIES NAURU All Money is a matter of belief Adam Smith, Book III, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations 1776 In the realm of the senses, finance doesn’t count for much. It’s hard to quantify emotions and the nuanced complexities of human perception. Since antiquity, governments, emperors, presidents, prime ministers, kings and queens have set up bankers, traders and investors with special extra-territorial zones that create respite from the norms of regulations and import-export tax regimes and in return have asked for a steady stream of highly valued revenue for the public purse. On the other hand, human behavior in large numbers has all the hallmarks of what both mathematicians and behavioral economists like to call “emergent complexity” - we think, live, and exist in a world of numbers. And economics, the “dismal science” is a reflection of when we attempt to assign value to human activity. “Extra-territoriality” is a kind of no-place that mirrors early ideas of “eu- topos” (the operative word, topos, meaning land/scape): it’s a kind of place that could only exist in the absence of contingencies - at the interplay of the “special economic zone” and the “core” there is a mirror process of an extended choreography of storage and retrieval. It’s important to think of the broad contours of this structure as a repetoire of effects whose moving parts constitute an hyper abstract machinery of commerce whose core elements are derived from global trade routes and their interaction with the digital “network economy.” Before modernity, “extra-territorial” domains were concentrated in the Mediterranean basin, because of the many nations that competed for limited resources near Delos in Greco- Roman times, and in Venice, Genoa, Luxembourg and Marseilles during the Middle Ages. -

News and Updates Wednesday, 30 March 2016

Project SafeCom News and Updates Wednesday, 30 March 2016 Subscribe and become a member here: http://www.safecom.org.au/ref-member.htm 1. The Saturday Paper: Love Makes a Way members sit down and speak up 2. Guy Rundle: The end of Tony Abbott and the conservatives 3. Hugh de Kretser: NSW anti-protest laws are part of a corrosive national trend 4. Doctor protest in Greece boosts calls for Australian detention centre boycott 5. Seventy-year-old asylum seeker released from detention centre 6. MEDIA RELEASE: Immigration panics as Manus Court challenge looms 7. Manus detainees told they will be separated and resettled or repatriated 8. Manus Island detainees say PNG authorities preparing to clear out detention centre 9. Abbott's Sri Lanka comments 'excuse war crimes', Tamil refugee advocates say 10. New Film soon to be screened: Chasing Asylum 11. Taxpayers charged $6 million for Immigration Department telemovie 12. 'Hard to watch': Afghans react to $6m Australian film aimed at asylum seekers 13. Powerful Nauru families benefiting from Australian-funded refugee processing centre 14. Turnbull government accused of ineptitude as refugee visa scheme stumbles 15. Malcolm Turnbull linking refugee crisis to bombings 'dangerous', Belgian ambassador says 16. Julie Bishop faces criticism over refugees 17. Bali Process regional refugee summit overshadowed by Brussels terror attacks 18. Bali Process concludes successfully with new ministerial declaration on refugees 19. Iraqi Christians say relatives lives are at risk due to Australia's slow resettlement process 20. Fed Govt flags some refugees as security risks, while Iraqi and Syrian families wait for relatives 21. -

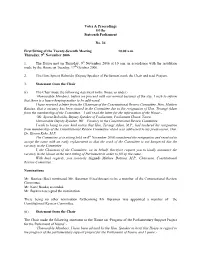

Votes & Proceedings

Votes & Proceedings Of the Sixteenth Parliament No. 34 First Sitting of the Twenty-Seventh Meeting 10.00 a.m. Thursday, 9th November 2006 1. The House met on Thursday, 9th November 2006 at 10 a.m. in accordance with the resolution made by the House on Tuesday, 17th October 2006. 2. The Hon. Sprent Dabwido (Deputy Speaker of Parliament) took the Chair and read Prayers. 3. Statement from the Chair (i) The Chair made the following statement to the House as under:- ‘Honourable Members, before we proceed with our normal business of the day, I wish to inform that there is a house-keeping matter to be addressed. I have received a letter from the Chairman of the Constitutional Review Committee, Hon. Mathew Batsiua, that a vacancy has been caused in the Committee due to the resignation of Hon. Terangi Adam from the membership of the Committee. I will read the letter for the information of the House:- ‘Mr. Sprent Dabwido, Deputy Speaker of Parliament, Parliament House, Yaren. Honourable Deputy Speaker, RE – Vacancy in the Constitutional Review Committee. I wish to bring to your kind notice that Hon. Terangi Adam, M.P., had tendered his resignation from membership of the Constitutional Review Committee which was addressed to my predecessor, Hon. Dr. Kieren Keke, M.P. The Committee at is sitting held on 6th November 2006 considered the resignation and resolved to accept the same with an early replacement so that the work of the Committee is not hampered due the vacancy in the Committee. I, the Chairman of the Committee, on its behalf, therefore request you to kindly announce the vacancy in the House at the next sitting of Parliament in order to fill up the same. -

18 April 2013 10.00Am

Votes and Proceedings of the 20th Parliament No. 30 Second sitting of the 20th meeting 18 April 2013 10.00am 1 Meeting of House The House met at 10.00am according to the resolution of the House made on 16 April 2013. Hon Ludwig Scotty (Speaker of Parliament) took the Chair and read Prayers. 2 Statement from Chair The Chair made the following statement: Gentlemen, very good morning to you all. Please give me time because I have two statements to present to the House this morning. My first statement is about the new Clerk, it is appropriate if I make it official because I have decided to appoint the new Clerk. Honourable members, I wanted to make it known that I have appointed Ms. Ann-Marie Thoma as the substantive Clerk of Parliament. You may have already been aware that Ann-Marie has done many years of good service to the Parliament and in other public roles of the Republic. And as of late, when Parliament had regretfully lost the service of our late Freddie Cain and the retirement of John Garabwan, both due to health reasons, she assisted myself and the top officials in our Parliament to put things into shape and ensure the smooth progress of this separate entity of the government of our country to operate business as usual and for the better. Ann-Marie has also worked closely in assisting her late brother, attending to official parliamentary duties in many areas. Hence, in considering her attentive reports and her knowledge of parliamentary work, and also my observance of her current role as acting clerk will leave me with no compunction but to be satisfied enough to appoint her to the highest post in the Parliament. -

Current Affairs Questions & Answers

CURRENT AFFAIRS QUESTIONS & ANSWERS PDF – MAY 2019 1. ______________, director of the groundbreaking 1991 movie about US inner city life “Boyz n the Hood,” died at the age of 51. a) Mose Se Sengo b) John Singleton c) Prospero Nograles d) Fatimih Dávila Answer b) John Singleton. John Singleton, director of the groundbreaking 1991 movie about US inner city life “Boyz n the Hood,” died Monday at the age of 51. Singleton directed “Boyz n the Hood” as a 22-year-old fresh out of film school. The flick described youth and violence in South Central Los Angeles, the bleak, gang-ridden neighborhood of his childhood. 2. Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman attended a key conclave of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in_____________. a) China b) Kazakhstan c) India d) Kyrgyzstan Answer d) Kyrgyzstan. Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman on Monday attended a key conclave of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in Kyrgyzstan and held bilateral meetings on its sidelines, including with her Chinese counterpart. 3. ____________was the world’s fourth biggest military spender in 2018 after United States, China and Saudi Arabia. a) Bhutan b) Nepal c) India d) Russia Answer c) India . India was the world’s fourth biggest military spender in 2018 after United States, China and Saudi Arabia, according to data released by Stockholm International Peace Research Institute on Tuesday. The institute report said the total world military expenditure rose to $1,822 billion in 2018, an increase of 2.6% from 2017. 4. _______________ to sell two-wheeler policies via WhatsApp. a) Bajaj Allianz Life Insurance b) Aviva India c) Bharti AXA General Insurance d) Birla Sun Life Insurance Answer c) Bharti AXA General Insurance . -

Legislative Council

New South Wales Legislative Council PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Fifty-Seventh Parliament First Session Wednesday, 5 June 2019 Authorised by the Parliament of New South Wales TABLE OF CONTENTS Motions .................................................................................................................................................... 57 Dr Don Weatherburn............................................................................................................................ 57 Documents ............................................................................................................................................... 57 Unproclaimed Legislation .................................................................................................................... 57 Tabling of Papers ................................................................................................................................. 57 Auditor-General ................................................................................................................................... 57 Reports ............................................................................................................................................. 57 Budget ..................................................................................................................................................... 57 Budget Estimates 2019 Timetable ....................................................................................................... 57 Bills