BBC Radio and Public Value: the Governance of Public Service Radio in the United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As Filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on July 2, 1998

AS FILED WITH THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION ON JULY 2, 1998 REGISTRATION NO. 333-57283 - ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- - ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 --------------- AMENDMENT NO. 1 TO FORM S-1 REGISTRATION STATEMENT UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 --------------- CROWN CASTLE INTERNATIONAL CORP. (EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER) DELAWARE 4899 76-0470458 (STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION (PRIMARY STANDARD (I.R.S. EMPLOYER OF INCORPORATION OR INDUSTRIAL IDENTIFICATION NUMBER) ORGANIZATION) CLASSIFICATION NUMBER) 510 BERING DRIVE SUITE 500 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77057 (713) 570-3000 (ADDRESS, INCLUDING ZIP CODE, AND TELEPHONE NUMBER, INCLUDING AREA CODE, OF REGISTRANT'S PRINCIPAL EXECUTIVE OFFICES) --------------- MR. CHARLES C. GREEN, III EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT AND CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER CROWN CASTLE INTERNATIONAL CORP. 510 BERING DRIVE SUITE 500 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77057 (713) 570-3000 (NAME, ADDRESS, INCLUDING ZIP CODE, AND TELEPHONE NUMBER, INCLUDING AREA CODE, OF AGENT FOR SERVICE) --------------- COPIES TO: STEPHEN L. BURNS, ESQ. KIRK A. DAVENPORT, ESQ. CRAVATH, SWAINE & MOORE LATHAM & WATKINS 825 EIGHTH AVENUE 885 THIRD AVENUE NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 --------------- APPROXIMATE DATE OF COMMENCEMENT OF PROPOSED SALE TO THE PUBLIC: As soon as practicable after the effective date of this Registration Statement. If any of the securities being registered on this Form are to be offered on a delayed or continuous basis pursuant to Rule 415 under the Securities Act of 1933, check the following box. [_] If this Form is filed to register additional securities for an offering pursuant to Rule 462(b) under the Securities Act, check the following box and list the Securities Act registration statement number of the earlier effective registration statement for the same offering. -

Police and Crime Commissioner's Diary 2018 1St July – 31St July Date

Police and Crime Commissioner’s Diary 2018 1st July – 31st July Date Time Engagement Mon 2nd 07:00-07:30 BBC Radio Cambridgeshire Telephone Interview 09:00-11:30 South Cambridgeshire Public Surgery 13:00-14:00 Meeting with Weightmans 15:00-16:00 Strategic Advisory Group Meeting 16:00-16:30 Meeting re Motorbike Judging Tue 3rd-Thu All Day Local Government Association Annual Conference 5th Fri 6th 07:00-07:30 BBC Radio Cambridgeshire Telephone Interview 10:00-11:00 Telephone Meeting with Assistant Chief Constable 11:00-11:30 Meeting with Personal Assistant 12:00-13:00 Conference Call with APCC 13:30-14:00 Meeting with Senior Policy Officer 14:00-14:30 Heart FM Radio Telephone Interview 15:30-16:00 Connect FM Radio Telephone Interview Mon 9th 10:00-12:00 A14 Safety Campaign 13:00-14:00 Telephone Conference with Chair of Police and Crime Panel 14:00-16:00 Combined Authority Leaders Strategy Session 17:15-17:45 BBC Radio Cambridgeshire Telephone Interview 18:30-21:00 Ramsey Million Partnership – Celebrate the Difference Event Tue 10th 11:00-13:00 Eastern Regions Pre-Meeting 14:00-17:00 Eastern Regions Meeting Wed 11th 09:00-17:00 Chief Constable Interviews Thu 12th 07:00-07:30 BBC Radio Cambridge Telephone Interview 11:00-12:40 Criminology Course Visit – Queen Katharine’s Academy, Peterborough 14:00-15:30 Pre-Brief for Police and Crime Panel 18:30-00:00 Police Bravery Awards Fri 13th 09:30-11:30 Finance Sub Group 11:30-12:00 Meeting with Head of Strategic Partnerships & Commissioning 12:15-13:15 Meeting with Chief Constable 13:15-17:00 Annual -

BBC Radio Frequency Finder

BBC Radio Frequency Finder For transmitter details see: BBC RADIO 5 LIVE RADIOS 1, 2, 3 AND 4 FM FREQUENCIES Digital Multiplexes (98% stereo coverage, ~100% mono) FM Transmitters by Region Format: News, Sport and Talk; Based Manchester Area R1 R2 R3 R4 AM Transmitters by Region United Kingdom (BBC Mux) DABm 12B SOUTH AND SOUTH EAST ENGLAND FM and AM transmitter details are also included in the London and South East England AM 909 London & South East England 98.8 89.1 91.3 93.5 frequency-order lists. South East Kent AM 693 London area 98.5 88.8 91.0 93.2 East Sussex Coast AM 693 Purley & Coulsdon, London 98.0 88.4 90.6 92.8 National Brighton and Worthing area AM 693 Caterham, Surrey 99.3 89.7 91.9 94.1 South Hampshire and Wight AM 909 Leatherhead area, Surrey 99.3 89.7 91.9 94.1 Radios 1 to 4 are based in London. See tables at end for Bournemouth AM 909 West Surrey & NE Hampshire 97.7 88.1 90.3 92.5 details of BBC FM network. Stations broadcast 24 hours a day Devon, Cornwall and Dorset AM 693 Reading 99.4 89.8 92.0 94.2 except where stated otherwise. Exeter area AM 909 High Wycombe 99.6 90.0 92.2 94.4 West Cornwall AM 909 Newbury & West Berkshire 97.8 88.2 90.4 92.6 South Wales and West England AM 909 West Berkshire & East Wilts 98.4 88.9 91.1 93.3 ADIO BBC R 1 North Dyfed and SW Gwynedd AM 990 Basingstoke 99.7 90.1 92.3 94.5 Format: New Music and Contemporary Hit Music with Talk The Midlands AM 693 East Kent 99.5 90.0 92.4 94.4 United Kingdom (BBC Mux) DABs 12B Norfolk and Suffolk AM 693 Folkestone area 98.3 88.4 90.6 93.1 United Kingdom (see table) FM 97.1, 97.7 - 99.8 Yorkshire, NW England & Wales AM 909 Hastings 97.7 89.6 91.8 94.2 Satellite 0101/700, DTT 700, Cable 901 South Cumbria & N Lancashire AM 693 Bexhill 99.2 88.2 92.2 94.6 Airdate: 30/9/1967. -

BBC Local Radio, Local News & Current Affairs Quantitative Research

BBC Local Radio, Local News & Current Affairs Quantitative Research August - September 2015 A report by ICM on behalf of the BBC Trust Creston House, 10 Great Pulteney Street, London W1F 9NB [email protected] | www.icmunlimited.com | +44 020 7845 8300 (UK) | +1 212 886 2234 (US) ICM Research Ltd. Registered in England No. 2571387. Registered Address: Creston House, 10 Great Pulteney Street, London W1F 9NB A part of Creston Unlimited BBC Trust Local Services Review, 2015 - Report Contents Executive summary .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Background and methodology ................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Presentation and interpretation of the data ......................................................................... 7 2. BBC Local Radio ...................................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Types of local news and information consumed – unprompted ......................................... 11 2.4 Times of day BBC Local Radio is listened to, tenure with station and hours per week listened .......................................................................................................................................... -

BBC Radio Post-1967

1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Operated by BBC Radio 1 BBC Radio 1 Dance BBC Radio 1 relax BBC 1Xtra BBC Radio 1Xtra BBC Radio 2 BBC Radio 3 National BBC Radio 4 BBC Radio BBC 7 BBC Radio 7 BBC Radio 4 Extra BBC Radio 5 BBC Radio 5 Live BBC Radio Five Live BBC Radio 5 Live BBC Radio Five Live Sports Extra BBC Radio 5 Live Sports Extra BBC 6 Music BBC Radio 6 Music BBC Asian Network BBC World Service International BBC Radio Cymru BBC Radio Cymru Mwy BBC Radio Cymru 2 Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Cymru Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Gwent BBC Radio Wales Blaenau Gwent, Caerphilly, Monmouthshire, Newport & Torfaen BBC Radio Deeside BBC Radio Clwyd Denbighshire, Flintshire & Wrexham BBC Radio Ulster BBC Radio Foyle County Derry BBC Northern Ireland BBC Radio Ulster Northern Ireland BBC Radio na Gaidhealtachd BBC Radio nan Gàidheal BBC Radio nan Eilean Scotland BBC Radio Scotland BBC Scotland BBC Radio Orkney Orkney BBC Radio Shetland Shetland BBC Essex Essex BBC Radio Cambridgeshire Cambridgeshire BBC Radio Norfolk Norfolk BBC East BBC Radio Northampton BBC Northampton BBC Radio Northampton Northamptonshire BBC Radio Suffolk Suffolk BBC Radio Bedfordshire BBC Three Counties Radio Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire & North Buckinghamshire BBC Radio Derby Derbyshire (excl. -

Local Radio, with Only 15 out of the 39 Stations Currently Regularly Broadcasting Their Own Shows During This Slot

BBC Trust Changes to Local Radio Assessment of significance May 2012 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers BBC Trust / Assessment of significance Contents The Trust’s decision 1 Background to the Trust's consideration 2 Test of significant change 7 Impact 7 Financial implications 14 Novelty 15 Duration 15 May 2012 BBC Trust / Assessment of significance The Trust’s decision The Trust has considered the BBC's proposal to make changes to Local Radio provision, and has formed the view that the proposals do not constitute a significant change to the UK Public Services. It has therefore decided that a Public Value Test is not required in order to make a decision. In reaching this view the Trust considered the likely impact of the proposals on users of the services and on others, the financial impact, the novelty of the proposals and their proposed duration. • Impact on users – likely to be limited due to the off-peak nature of many of the proposals, and the nature of the new All England shared programming in the 19:00 – 22:00 weekday slot • Impact on others – likely to be negligible due to the off-peak nature of most of the changes and the service licence for Local Radio which requires it to provide a distinctive service targeting listeners aged 50 and over, who are not well-served elsewhere • Financial impact – the changes result in limited financial change • Novelty – the changes proposed are not novel • Duration – the proposed changes will be permanent, although the Trust is required to consider all the relevant factors under clause 25 and this alone does not mean the proposals constitute a significant change, taking account of the other factors. -

Business Wire Catalog

UK/Ireland Media Distribution to key consumer and general media with coverage of newspapers, television, radio, news agencies, news portals and Web sites via PA Media, the national news agency of the UK and Ireland. UK/Ireland Media Asian Leader Barrow Advertiser Black Country Bugle UK/Ireland Media Asian Voice Barry and District News Blackburn Citizen Newspapers Associated Newspapers Basildon Recorder Blackpool and Fylde Citizen A & N Media Associated Newspapers Limited Basildon Yellow Advertiser Blackpool Reporter Aberdeen Citizen Atherstone Herald Basingstoke Extra Blairgowrie Advertiser Aberdeen Evening Express Athlone Voice Basingstoke Gazette Blythe and Forsbrook Times Abergavenny Chronicle Australian Times Basingstoke Observer Bo'ness Journal Abingdon Herald Avon Advertiser - Ringwood, Bath Chronicle Bognor Regis Guardian Accrington Observer Verwood & Fordingbridge Batley & Birstall News Bognor Regis Observer Addlestone and Byfleet Review Avon Advertiser - Salisbury & Battle Observer Bolsover Advertiser Aintree & Maghull Champion Amesbury Beaconsfield Advertiser Bolton Journal Airdrie and Coatbridge Avon Advertiser - Wimborne & Bearsden, Milngavie & Glasgow Bootle Times Advertiser Ferndown West Extra Border Telegraph Alcester Chronicle Ayr Advertiser Bebington and Bromborough Bordon Herald Aldershot News & Mail Ayrshire Post News Bordon Post Alfreton Chad Bala - Y Cyfnod Beccles and Bungay Journal Borehamwood and Elstree Times Alloa and Hillfoots Advertiser Ballycastle Chronicle Bedford Times and Citizen Boston Standard Alsager -

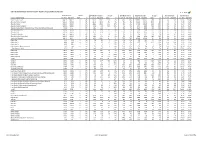

Hallett Arendt Rajar Topline Results - Wave 4 2016/Last Published Data

HALLETT ARENDT RAJAR TOPLINE RESULTS - WAVE 4 2016/LAST PUBLISHED DATA Population 15+ Change Weekly Reach 000's Change Weekly Reach % Total Hours 000's Change Average Hours Market Share LOCAL COMMERCIAL Last Pub W4 2016 000's % Last Pub W4 2016 000's % Last Pub W4 2016 Last Pub W4 2016 000's % Last Pub W4 2016 Last Pub W4 2016 Bauer Radio - Total 54029 54029 0 0% 17873 17597 -276 -2% 33% 33% 156567 157032 465 0% 8.8 8.9 15.1% 15.0% Absolute Radio Network 54029 54029 0 0% 4471 4530 59 1% 8% 8% 31401 33073 1672 5% 7.0 7.3 3.0% 3.2% Absolute Radio 54029 54029 0 0% 2643 2141 -502 -19% 5% 4% 17996 15520 -2476 -14% 6.8 7.2 1.7% 1.5% Absolute Radio (London) 12015 12015 0 0% 894 750 -144 -16% 7% 6% 4707 4125 -582 -12% 5.3 5.5 2.3% 2.0% Absolute Radio (West Midlands) (was Planet Rock (West Midlands)) 3728 3727 -1 0% 242 251 9 4% 6% 7% 1573 2066 493 31% 6.5 8.2 2.3% 3.1% Absolute Radio 70s 54029 54029 0 0% 280 270 -10 -4% 1% *% 1147 1288 141 12% 4.1 4.8 0.1% 0.1% Absolute 80s 54029 54029 0 0% 1458 1529 71 5% 3% 3% 8080 8955 875 11% 5.5 5.9 0.8% 0.9% Absolute Radio 90s 54029 54029 0 0% 703 727 24 3% 1% 1% 2716 2971 255 9% 3.9 4.1 0.3% 0.3% Absolute Radio Classic Rock 54029 54029 0 0% 646 703 57 9% 1% 1% 2856 3316 460 16% 4.4 4.7 0.3% 0.3% Bauer City Network 54029 54029 0 0% 6999 6947 -52 -1% 13% 13% 60344 60303 -41 0% 8.6 8.7 5.8% 5.8% Radio Aire 639 639 0 0% 79 86 7 9% 12% 13% 470 546 76 16% 6.0 6.4 4.1% 5.1% Radio Aire 2 988 988 0 0% 62 62 0 0% 6% 6% 857 735 -122 -14% 13.9 11.9 4.6% 4.2% Radio Aire 3 639 640 1 0% 4 3 -1 -25% 1% 1% 8 9 1 13% 2.0 2.6 0.1% 0.1% Radio Borders (Bauer Borders) 109 109 0 0% 54 51 -3 -6% 50% 47% 674 709 35 5% 12.4 13.8 34.3% 35.1% C.F.M. -

Opinion: the Future of AM Radio England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

Frequency Finder (www.frequencyfinder.org.uk) Opinion: The Future of AM Radio England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland Summary AM radio in the British Isles is now in terminal decline and may be discontinued completely during the mid-to-late 2020s. With the BBC subject to budget cuts and commercial stations vulnerable to a potential advertising recession, all broadcasters will be looking to reduce their AM transmission costs. Inevitably, those stations with a relatively small proportion of their listening via AM are likely to close their AM transmitters before those stations with much larger AM audiences. This article explores how this process could be managed smoothly so that AM transmission costs are gradually reduced in proportion to the number of listeners continuing to use AM. For high-power transmitters, substantial cost savings can be made by simply reducing the transmission power; a 50% reduction would have minimal impact on audience size. For low-power transmitters, there are two issues to consider: the audience size for each transmitter and the number of transmitters operating at that site. The more low-power transmitters that share a site, the lower the operating cost per transmitter. Thus, closure decisions should be based on cost per AM listener and coordination between different broadcasters is needed. With 26 major broadcasters’ AM transmitters closed in 2018, 33 closed in 2020 and at least 21 closing during 2021, this process has now begun. Background AM was the dominant listening medium for radio in the British Isles until the mid 1980s, when it was overtaken by FM. In the early 1990s, with improvements in FM coverage and wide access to FM radios, it was decided to mostly abandon simulcasting in the UK and launch new stations on AM. -

BBC Performance Tracker 2019 Questionnaire

GfK BBC Performance Tracker V37 272.201.20323 I. SAMPLE VARIABLES RESEARCHER: If there are questions or variables that are not quotas and you want to track them, list the variable name and type here, so programming knows that you want to monitor. II. QUOTA CHECK BASED ON SAMPLE VARIABLES RESEARCHER: Insert description of the quota based on sample information. Sample plan to be provided separately. III. INTRODUCTION We are conducting a study looking at people’s attitudes to television, radio and online services in the UK, and we are keen to know your views. This study is being carried out for Ofcom (the Office of Communications), which is responsible for overseeing broadcast services in the UK. Your answers to the survey will remain completely confidential. They will never be reported on at an individual level or be used to identify you in any way. The information collected by GfK is on behalf of, and will remain, the property of Ofcom and will not be passed on to any third parties. First, we will ask you a few questions about yourself and the media you use. This will only take a few minutes. This will allow us to see whether you qualify to complete the full survey. The full survey will take 20-25 minutes depending on the media you use. IV. SCREENER BASE: ALL RESPONDENTS INTERNET USE INTU [S] In the past week, how many hours have you spent using the internet? This includes email, social media, online shopping, online gaming, browsing/searching or using apps, or watching TV programmes, films and videos, or listening to music and radio programmes online. -

BBC Executive Priorities and Summary Workplan for 2011/12

Blaenoriaethau a chrynodeb o gynllun gwaith Bwrdd Gweithredol y BBC ar gyfer 2011/12 Datganiad gan yr Uwch Gyfarwyddwr Annibynnol Y cynllun gwaith hwn ar gyfer y BBC yw rhifyn cyntaf cyhoeddiad blynyddol newydd. Mae’n crynhoi strategaeth, amcanion a chyllideb amlinellol y BBC ar gyfer y flwyddyn sydd i ddod ynghyd â digwyddiadau unigol nodedig. Mae cyhoeddi’r cynllun gwaith hwn yn rhan o ymrwymiad y BBC i fod yn agored a thryloyw, i Ymddiriedolaeth y BBC ac i dalwyr ffi’r drwydded. Mae’r ddogfen hefyd yn rhan bwysig o’r ffordd y byddaf i, fel Uwch Gyfarwyddwr Annibynnol y BBC, ar y cyd â’m cyd-gyfarwyddwyr anweithredol ar Fwrdd Gweithredol y BBC, yn sicrhau bod y BBC yn cyflawni ei strategaeth a’i hymrwymiadau yn unol â disgwyliadau Ymddiriedolaeth y BBC a thalwyr ffi’r drwydded. Nid yw’r ddogfen hon yn lasbrint ar gyfer y flwyddyn sydd i ddod. Bydd y cynlluniau’n sir o newid mewn meysydd penodol gan addasu i wahanol ddigwyddiadau. Fodd bynnag, mae gan y BBC strategaeth glir yn Rhoi Ansawdd yn Gyntaf a, gyda setliad ffi’r drwydded ym mis Hydref 2010, mae ganddi fframwaith cyllidebol clir i weithio iddo. Pryd bynnag y bydd ein cynlluniau yn newid, mae’n rhaid iddynt barhau i ganolbwyntio ar gyflawni ein strategaeth, a hynny o fewn ein cyllideb. Bwriedir i’r cynllun gwaith blynyddol gynorthwyo i sicrhau bod ein gwaith o ddydd i ddydd yn cyd-fynd â’n strategaeth hirdymor a’n cyllideb. Mae aelodau anweithredol Bwrdd Gweithredol y BBC yn edrych ymlaen at weithio gyda’r Cyfarwyddwr Cyffredinol i roi cynnwys y cynllun gwaith hwn ar waith ac rwy’n ei gymeradwyo i Ymddiriedolaeth y BBC. -

News Articles Related to IVF Articles

Appendix 5: News articles related to IVF IVF decision made on: 05/09/2017 Articles 25/01/2019 Cambs Times Woman backs health campaign to get IVF reinstated on the NHS 25/01/2019 Wisbech Standard Woman backs health campaign to get IVF reinstated on the NHS 23/01/2019 The Hunts Post Lobby group calls for IVF funding cut to be reversed 17/01/2019 Peterborough Telegraph Call to reverse IVF cuts 14/01/2019 Wisbech Standard ‘It would destroy me if we couldn’t have a baby’: Wisbech woman backs Healthwatch campaign to get IVF reinstated on the NHS 11/01/2019 Peterborough Telegraph Peterborough health group calls for city IVF cuts to be reversed 20/01/2019 Healthwatch Fertility service suspension to be reviewed 01/01/2019 Daily Mail Hope for childless couples as MPs vote to end 'disgraceful' IVF postcode lottery 21/11/2018 Fenland Citizen NEWLY-WEDS IN IVF CROWD FUNDING BID 30/10/2018 Bourne Hall NHS IVF funding in the East of England 25/08/2018 Daily Mail Radical new approach to IVF 'DOUBLES the chance of getting pregnant to 62 per cent', say experts 26/07/2018 Cambridge News Gay couple’s struggle to have a child 25/07/2018 Cambridge News IVF is 40 – but desperate couples in Cambridgeshire still can't get NHS funding for it 20/07/2018 BBC News online IVF: NHS couples 'face social rationing' 30/06/2018 Daily Mail Postcode lottery for couples as IVF is axed by NHS as bosses cut costs with recommended three cycles of treatment being offered by just one in 10 areas in UK 29/06/2018 Guardian, The IVF services slashed in England as