Net Art's Alternative Currencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

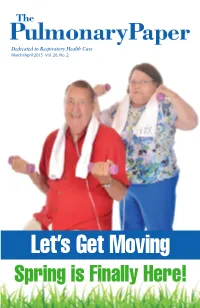

Let's Get Moving

The PulmonaryPaper Dedicated to Respiratory Health Care March/April 2015 Vol. 26, No. 2 Let’s Get Moving Spring is Finally Here! Table of Contents We are hiding The Pulmonary Paper logo on our front cover. Can you find it? On the Cover: Friends Jerry Featuring Knotts from Florida and Alma 03 | Editor‘s Note McCann from South Carolina get in shape for Spring! 04 | Calling Dr. Bauer 06 | Ask Mark For Fun 08 | The Ryan Report Your Health 17 | A New Recipe to Try! 10 | Fibrosis File 28 | SeaPuffer Cruises: 13 | People: The Plus in Alaska, Panama 18 | Sharing the Health Pulmonary Rehab Canal, Mexico … 30 | Respiratory News 15 | CDC Advice on Where do you want Pneumonia to go? Vaccinations 22 | Have a Plan to Manage Your Health 25 | Radon in Your Home: A Second Opinion Live Longer! Breathe Easier! Improve Quality of Life! Even Look Better! Talk to your doctor now about the benefits of Transtracheal Oxygen Therapy! • Improved mobility • Greater exercise capacity • Reduced shortness of breath • Improved self-image • Longer lasting portable oxygen sources • Eliminated discomfort of the nasal cannula • Improved survival compared to the nasal cannula You’ve suffered long enough. Ask your doctor about TTO2! For information call: 1-800-527-2667 or e-mail [email protected] 2 www.pulmonarypaper.org Volume 26, Number 2 Editor’s Note aving chronic lung problems, you not only have to deal with your medical symptoms but also the “social” symptoms. HYou know your limitations but it is hard to watch your friends do things you can no longer physically do. -

Laura Olson Laura Olson Photographer in His Grace Photography

308 North Street Easton, MD 21601 (410) 714- 0000 [email protected] 2013/2014 (Effective October 1st 2013) Dear Bride and Groom, Thank you for contacting me. I am excited to tell you that I have your date available. I wish to congratulate you once again on your recent proposal. What an exciting time! I know planning may be a stressful time but do take every opportunity to enjoy these moments that will lead up to one of the most significant days of your life. When it comes to planning your wedding, finding a photographer is one of the most important decisions you will make. Style, personality and design options are all important. My style is mostly documentary and photojournalism. I love my job and the opportunity to capture real moments. You will never have the opportunity again to get back every emotion and feeling that you feel on your wedding day. I try to give some of that back to you. I consider myself an artist and love my craft! It is such a wonderful opportunity to be a part and capture the moments of your day, but will do some relaxed posed shots as well as the need arises. Please feel free to contact me at any time with questions and concerns you may have. Booking season is upon us, and dates fill up quickly. If you have not already, I encourage you to take a look at my portfolio online at http://www.inhisgracephotography.com. You may also see some of my full weddings at http://inhisgracephotography.com/index.php. -

Making Metadata: the Case of Musicbrainz

Making Metadata: The Case of MusicBrainz Jess Hemerly [email protected] May 5, 2011 Master of Information Management and Systems: Final Project School of Information University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 Making Metadata: The Case of MusicBrainz Jess Hemerly School of Information University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 [email protected] Summary......................................................................................................................................... 1! I.! Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2! II.! Background ............................................................................................................................. 4! A.! The Problem of Music Metadata......................................................................................... 4! B.! Why MusicBrainz?.............................................................................................................. 8! C.! Collective Action and Constructed Cultural Commons.................................................... 10! III.! Methodology........................................................................................................................ 14! A.! Quantitative Methods........................................................................................................ 14! Survey Design and Implementation..................................................................................... -

The Oxford Democrat : Vol. 72. No.47

The Oxford NUMBER 47. VOLUME 72. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 1905. "Wants lue to pay ber fare! I see dredge, wan situated In a hollow close come out of the car. That woman at M STEWART, M. D., Supply of Birds. 1». AMONG THE FARMERS, i myself doln* it! I've got ways enough to the house. In a few moments the the house is the real Marthy Snow all to spend iny money without payln' three were inside, with a sawhorse right, and we've got to go right up WILL PBOBABLY BE MUCH " TURKEYS OUR WEEKLY BfEKD TH* FLOW." fares for Nantucket folke." against the door. there and nee her. Come on!" and Surgvon, LAST SEASON. Physician THE SAME AS "If you and she vigu urticles, as sh· They heard the rattle o( a heavy car- But Captain Jerry mutinied outright. culls it, you'll have to pay more than riage, and, crowding together at the He declared that the eight of that dar- on prmcUc&i agricultural topic· Maxim Block, South Puis. Correspondence be of in α mut- cobwebbed saw the black him of for- U solicite· t Address all communications In- Already the proud turk, gaudy fares," said Captain Perez window, ky had sickened marrying NEW YORK LETTER tended for this department to Hknsy D. plumage, is aware of the shadow which ter of fact tone. "I think same as Erl shaj>e of the depot wagon rock past ever and thut he would not see the Agricultural Editor Oxford Dent is a fore- » C. -

FOREVER Indie’S Biggest Platform Hero Makes His Bloody Return

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES SUPER MEAT BOY FOREVER Indie’s biggest platform hero makes his bloody return Issue 17 £3 wfmag.cc Prison Architect Story mode Introversion’s dramatic How games generate fall and triumphant rise atmosphere with words UPGRADE TO LEGENDARY AG273QCX 2560x1440 As originally intended e’re in trouble. Slowly, every day, we Emulators, then, are pixel-perfect to the point of lose a little bit of our history. Another imperfection. They’ve tricked us all into believing they’re capacitor pops. Another laser dims. right. But there’s another, more invisible, and more W Another cathode ray tube fails. It’s deadly trick that emulators play on us: input lag. becoming increasingly hard for future generations to Emulators inherently introduce additional time from accurately trace how we got to today. WILL LUTON an input being made to the result being displayed on Yet, it’s a better time than ever to play retro games. the screen. Emulator lag is often in the realm of two Will Luton is a veteran Following Nintendo’s little NES and SNES consoles, we or three frames, or 0.04 seconds. While that might not game designer and have an onslaught of chibi, HDMI-compliant devices. product manager seem like much, especially considering human reaction Sega’s Mega Drive Mini is nearly with us, and we have who runs Department times to visual stimulus are 0.25 seconds, you notice it. news of a baby PC Engine gestating. But they all sit atop of Play, the games Consciously or not. -

The Breeze, Was First Published in October 1982

James Madison University Thursday, September 6,1864 Vol.62 No. 3 Police praise policefile By Sandy Stone staff writer Campus ' drunken driving arrests at JMU decreased 24 percent from 1982 to 1983 — and campus police attribute the drop in part to policefile. Policefile, which publishes the names of students charged with offenses such as drunken driving and public drunkenness in a weekly column in The Breeze, was first published in October 1982. Although it first sparked criticism from campus administrators, police now support policefile because they think it acts as a deterrent. "The first real measureable decrease in drunken driving ar- rests occurred after policefile started being published," said Alan MacNutt, director of cam- pus police. "The fact that names were published, plus in- creased attention paid to speakers and programs on campus that focused on drunken driving, had a significant impact on the decrease," MacNutt said. From 1982 to 1983, the number of drunken driv- ing arrests on campus went from 74 to 56, Mac- Nutt said. Conversely, the number of people charged with drunken driving by city police in Harrisonburg and Rockingham County during the same two years in- creased by 14 percent, according to Capt. M.L. Stroble of the Harrisonburg police department. The number of arrests made in 1982 was 390, compared with 445 in 1983. The Daily News- Record, Harrisonburg's local newspaper, does not publish drunken driving arrests or convictions. During/the summer, MacNutt recommended to the Hamsonburg-Rockingham Task Force on Drunk Driving that names of those charged with drunken driving be published by local media. -

Richardjamesburgessdoctorald

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY: THE EVOLVING ROLE OF THE MUSICIAN RICHARD JAMES BURGESS A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2010 ii Copyright © 2010 by Richard James Burgess All Rights Reserved ii 1 Structural Change in the Music Industry The Evolving Role of the Musician Abstract The recording industry is little more than one hundred years old. In its short history there have been many changes that have redefined roles, enabled fortunes to be built and caused some to be dissipated. Recording and delivery formats have gone through fundamental conceptual developments and each technological transformation has generated both positive and negative effects. Over the past fifteen years technology has triggered yet another large-scale and protracted revision of the business model, and this adjustment has been exacerbated by two serious economic downturns. This dissertation references the author’s career to provide context and corroboration for the arguments herein. It synthesizes salient constants from more than forty years’ empirical evidence, addresses industry rhetoric and offers methodologies for musicians with examples, analyses, and codifications of relevant elements of the business. The economic asymmetry of the system that exploits musicians’ work can now be rebalanced. Ironically, the technologies that triggered the industry downturn now provide creative entities with mechanisms for redress. This is a propitious time for ontologically reexamining music business realities to determine what is axiological as opposed to simply historical axiom. The primary objective herein is to contribute to the understanding of applied fundamentals, the rules of engagement that enable aspirants and professionals alike to survive and thrive in this dynamic and capricious vocation. -

January 2003 Modern Drummer January 2003 5 Contents Contentsvolume 27, Number 1 Cover Photo by Alex Solca Inset Photo by Paul La Raia PAUL MCCARTNEY’S ABE LABORIEL JR

RINGO’S TOP-15 • ADEMA • ALAN WHITE PLAYBACK ABE LABORIEL JR. MASTERFUL WITH MCCARTNEY PLUS, SIR PAUL CHATS WITH MD! ROBBY AMEEN MAKING HISTORY WITH ”EL NEGRO“ RASHIED ALI A CONVERSATION WITH BOB MOSES DAVE WECKL’S HOTTEST LATIN LICKS $4.99US $6.99CAN 01 IT’S SHOWTIME! OOKS T TICK WIRLING MD LOOKS AT STICK TWIRLING 0 74808 01203 9 For an Alan White poster, send $4.00 to Ludwig Industries, Alan White poster, P.O. Box 310, Elkhart, IN 46515 Web site: www.ludwig-drums.com CLASSIC MAPLE SERIES. THE BEST SOUNDING DRUMS. Alan White Photographed By Dennis J. Slagle 4 Modern Drummer January 2003 Modern Drummer January 2003 5 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 1 Cover photo by Alex Solca Inset photo by Paul La Raia PAUL MCCARTNEY’S ABE LABORIEL JR. One of drumming’s hottest stars of the studio and stage, Abe Laboriel Jr. seems to be everywhere these days—Paul McCartney, Vanessa Carlton, Sting…. One good listen, and you’ll know why. by Robyn Flans EXCLUSIVE! Sir Paul Talks Drums With MD 54 Alex Solca UPDATE 24 LATIN GREAT Def Leppard’s RICK ALLEN ROBBY AMEEN 74 Adema’s KRIS KOHLS Alex Solca As good a tutorial as Funkifying The Clave is, it Phish’s JON FISHMAN gives little indication of how powerful a drum- Counting Crows’ BEN MIZE mer its author is. A killer new album with the equally gifted Horacio “El Negro” Hernandez STEVE HOUGHTON gives us ample reason to pick this guy’s brain. Southside Johnny’s LOUIE APPEL by Ken Micallef NEW COLUMN! FREE-JAZZ TRAILBLAZER PLAYBACK 154 RASHIED ALI 90 ALAN WHITE When John Coltrane asks a drummer to join Before he joined one of the blazingest pro- his band—with Elvin Jones—it should come gressive bands ever, dynamic Yes stick man as no surprise when he’s soon acknowl- Alan White worked with British rock’s royal- edged as a player of enormous talent and ty. -

Turbulent Mixing in Experimental Ecosystem Studies

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 161: 265-293. 1997 Published December 31 Mar Ecol Prog Ser REVIEW Turbulent mixing in experimental ecosystem studies Lawrence P. Sanford* University of Maryland, Center for Environmental Science, Horn Point Laboratory, PO Box 775, Cambridge. Maryland 21613, USA ABSTRACT. Turbulent mixing is an integral aspect of aquatic ecosystems Turbulence affects eco- system features ranglng from phytoplankton blooms at large scales through microscale interactions in the plankton. Enclosed experimental ecosystems, if they are to mimic the function of natural ecosys- tems, also must mimic natural turbulence and its effects. Large-scale velocity gradients and unstable buoyancy fluxes generate turbulent mixing in nature, most often at the surface and bottom boundaries and in the pycnocline. Large eddy sizes are controlled by the mixed layer depth, boundary layer thick- ness, or overturning length in the pycnocl~ne.Turbulent energy cascades through smaller and smaller eddy scales until it can be dissipated by molecular viscosity at the smallest scales. In contrast, artificial apparatuses frequently are used to generate turbulent m~xingin the interior of experimental ecosystem enclosures Large eddy sizes are controlled by the size of the generation apparatus, and they usually are much smaller than in nature Mismatched large eddy length scales and differences in turbulence generation mechanisms are responsible for the difficulties in mimicking natural turbulent mixing in experimental enclosures. The 2 most important turbulence parameters to consider in experimental ecosystem research are overall mixing time, T,,,, and turbulence dissipation rate, E. If the levels, spatial dlstribut~ons,and temporal variability of T,,, and E can be matched between an enclosure and the nat- ural system it IS to model, then potential mixing artifacts can be minimized. -

Night; in Another:1

�1!I'J'ABLlIiHEJ). 111"6"3. PAGES WEEKL"l_. VOL. X;l:IV;No. 48. } TOPEKA, KANSAS, DECEMBER ·.1, 1886'. {SIXTEENPRICE. 81.50 A YEAR.. betng composed almost enttrely of Indlges- Ing a thousand·pounds while kllPt o� !tood sick; In another eleven out of twenty-three IND.IGES·TION IN CATTLE. tible eullulose and woody fiber. Even the food. Very rich food may be digested with died within two weeks; and in still another buft'alo grass, which in times gone by was a1esser quantity. The more dry and Innu- twenty-three out of forty-seven dl� wltbhi [Bynonyms.-Dry Murrain, Bloody Mur- considered a superior article of winter food tr.itious the food the greater must be the sup- four weeks.· These are by no means exeep- Imnactlon of the Stomach rain, Stomacll, of Its for cattle; has, of late years, lost much Diy of water. Cornstalks and poor prairie tlonal cases. , Staggers, Maw-bound, Enteritis.] vaunted to the late autumn the of from an animal has for a DEFINITION!I reputation owing hay require consumption nlnet;v When been kept Jong rains washing out the most of its nutritious to one hundred pounds of water per day for time on poor coarse food the sym-pto.ms the head of I are Under indigestion propose elements. each animal of a thousand pounds. This more slowly developed and death not so sud- to treat of all those of the di- derangements Such food, poor In beat-producing ole- Immense mass of water must be raised to the den. -

Bronchiectasis Basics Airway Wall Eople with Bronchiectasis Have a Con Pstant Battle with Raising Secretions

The PulmonaryPaper Dedicated to Respiratory Health Care January/February 2015 Vol. 26, No. 1 Happy Valentines Day! Table of Contents We are hiding The Pulmonary Paper logo on our front cover. Can you find it? Featuring For Fun 03 | Editor‘s Note 13 | Two Recipes to Try! 04 | Calling Dr. Bauer 28 | SeaPuffer Cruises Plan a vacation and 06 | The Ryan Report leave your cares 08 | Ask Mark Your Health behind you! 10 | Fibrosis File 12 | Maintaining Weight with COPD 18 | Sharing the Health 15 | Bronchiectasis 30 | Respiratory News Basics 17 | New Quiz! 22 | 2014 Tax News 25 | Flu News 26 | Testing for Radon Gas in Your Home Live Longer! Breathe Easier! Improve Quality of Life! Even Look Better! Talk to your doctor now about the benefits of Transtracheal Oxygen Therapy! • Improved mobility • Greater exercise capacity • Reduced shortness of breath • Improved self-image • Longer lasting portable oxygen sources • Eliminated discomfort of the nasal cannula • Improved survival compared to the nasal cannula You’ve suffered long enough. Ask your doctor about TTO2! For information call: 1-800-527-2667 or e-mail [email protected] www.pulmonarypaper.org Volume 25, Number 6 Editor’s Note artha from Virginia recently wrote saying, “I know I should exercise and have made it my number one Mresolution.” We hope you achieve your goal, Martha! The three things on our goal list are to educate, empower and encourage you to continue to enjoy life despite obstacles that you may have to overcome. Bob McCoy RRT of Valley Inspired Oxygen in Apple Valley, MN, put things into perspective recently when he talked about people’s reluctance to wear oxygen at an American Association of Respira tory Care meeting.