The Third Space of Fatih Akin's Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beşiktaş-Beyoğlu-Fatih Kağithane-Şişli Ilçeleri Heyelan Farkindalik Kitapçiği

1 Deprem Risk Yönetimi ve Kentsel İyileştirme Daire Başkanlığı Deprem ve Zemin İnceleme Müdürlüğü İSTANBUL İLİ BEŞİKTAŞ-BEYOĞLU-FATİH KAĞITHANE-ŞİŞLİ İLÇELERİ HEYELAN FARKINDALIK KİTAPÇIĞI PROJE BİLGİLERİ “İstanbul İli, Beşiktaş, Beyoğlu, Fatih, Kağıthane, Şişli İlçeleri Heyelan Farkındalık Kitapçığı”, Beşiktaş, Beyoğlu, Fatih, Kağıthane ve Şişli ilçe sınırları içerisindeki heyelan alanlarının mekânsal dağılımlarını, depremsiz ve depremli durum için tehlike analizlerini, heyelanların hareket etme biçimi ile aktivite durumlarını sunmak amacıyla “İstanbul İli, Heyelan Bilgi Envanteri Projesi (2020)” bilgileri kullanılarak, 2020 yılında İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi, Deprem Risk Yönetimi ve Kentsel İyileştirme Daire Başkanlığı, Deprem ve Zemin İnceleme Müdürlüğü (DEZİM) tarafından hazırlanmıştır. İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Deprem Risk Yönetimi ve Kentsel İyileştirme Daire Başkanlığı Deprem ve Zemin İnceleme Müdürlüğü: Harita Tek. Nurcan SEYYAR Jeofizik Yük. Müh. Yasin Yaşar YILDIRIM (Dai. Bşk. Danışmanı) Jeoloji Müh. Esra FİTOZ Jeoloji Müh. Nilüfer YILMAZ Jeoloji Müh. Pınar AKSOY Jeoloji Müh. Tarık TALAY Jeoloji Müh. İsra BOSTANCIOĞLU (Müdür Yrd.) Jeofizik & Geoteknik Yük. Müh. Kemal DURAN (Müdür) Dr. Tayfun KAHRAMAN (Daire Başkanı) HAZİRAN 2020, İSTANBUL Kıymetli Hemşehrilerim; Dünyada deprem riski en yüksek kentlerin başında, hem nüfus ve yapı yoğunluğu hem de fay hatlarına yakınlığı nedeniyle, maalesef İstanbul geliyor. Kadim kentimizde, değişmeyen öncelikte ve önemdeki birinci konu deprem riski ve beraberinde getireceği yıkımlardır. -

The Protection of Historical Artifacts in Ottoman Empire: the Permanent Council for the Protection of Ancient Artifactsi

Universal Journal of Educational Research 7(2): 600-608, 2019 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2019.070233 The Protection of Historical Artifacts in Ottoman Empire: The Permanent Council for the i Protection of Ancient Artifacts Sefa Yildirim*, Fatih Öztop Department of History, Faculty of Science and Letters, Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen University, Turkey Copyright©2019 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The historical artifacts that reveal the social, establishment, functioning, duties and activities of the political, aesthetic, moral, architectural, etc. stages, before-said council are tried to be explained. through which the human beings have been; which transfer and reveal information from past to present and Keywords Historical Artifacts, Protection of future; which have an artistic, historical or archaeological Historical Artifacts, Council importance are very important physical elements that the present-day civilized societies protect or must protect as cultural values. Such works both strengthen the ties to the past due to the transfer of cultural heritage to existing and 1 . Introduction future generations and plays a very important role in the writing of the past through the data provided to the The first initiative for the protection of the historical researchers. The protection of the historical artifacts was artifacts in the Ottoman Empire can be considered as the under sharia laws until 1858 in Ottoman Empire, since beginning of the storage of two collections of old weapons then, some regulations were done about this issue, in the and artifacts since 1846 in the Hagia Irene Church end, The Permanent Council for the Protection of Ancient (Sertoğlu & Açık, 2013, p.160). -

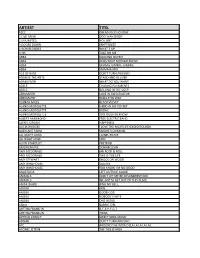

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

A View of the History of the Istanbul Faculty of Medicine

A VIEW OF THE HISTORY OF THE ISTANBUL FACULTY OF MEDICINE Prof. Dr. Nuran Yıldırım The Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, the Department of History of Medicine and Ethics Attributing the roots of the Istanbul Faculty of Medicine to the Fatih Darüşşifa after a great deal of discussion, the 500th anniversary of medical education in Istanbul was celebrated in 1970. The soundest documents showing that medical education was carried out in the Fatih Dârüşşifa were the appointment papers (rüus) of medical students for the dârüşşifa in the 60 years between 1723 and 1783. These nine rüus, which were recently published, clarify that there were positions for six medical students in the dârüşşifa, and that whenever a vacancy came up, a new medical student would be appointed by the chief physician to undergo a systematic medical training. 1-Archival document concerning Ismail Efendi‟s appointment in place of Derviş Mehmet in Fatih Darüşşifa after his death. With the opening of the Süleymaniye Medical Medrese, medical education in Istanbul, which had started with the Fatih Dârüşşifa, became institutionalized. The opening of a medical medrese for the first time in the Ottoman State is accepted as being an important step in our history of medical education. The Süleymaniye Medical Medrese (Süleymaniye Tıp Medresesi) was a medrese for specializing, or a “post-graduate” course, as only students who had completed their classic medrese education could continue. Not only did the physicians that were trained join the scholarly classes, but at the same time they could be qadi or rising even to the level of sheikh-ul-Islam or grand vizier. -

Fatih University Info Sheet

Fatih University Info Sheet Year of Foundation : 1996 City : Istanbul, Turkey Type (Public or Foundation) : Foundation Language of Instruction : Some programs are completely in English : Some programs are completely in Turkish (Please see course catalogue for further information) Web : www.fatih.edu.tr Course catalogue : http://erasmus.fatih.edu.tr Contact : [email protected] Fatih University was founded by Turkish Association of Health and Medical Treatment in 1996. Despite its young age, its envision is to become a leading university, that aims at theoretical and practical education, research and development, by participating in global developments and issues while remaining attentive to local perspectives. The main campus is located on the European side of Istanbul but our research hospital and Vocational School of Medical Sciences is located on the Asian side of the city. Additionally, there are two polyclinics in Istanbul. Fatih University prepares platforms for students to mix with different cultures, enjoying multiculturalism with international students on the campus. Brief History http://www.fatih.edu.tr/?tarihce&language=EN Faculties: 1. Medicine 2. Law 3. Engineering 4. Economics and Administrative Sciences 5. Arts and Science 6. Fine Arts, Design and Architecture 7. Education 8. Theology 9. Conservatory Institutes (Graduate Schools) 1. Science and Engineering 2. Social Sciences 3. Health Sciences 4. Biomedical Engineering 5. BioNano Technology Vocational Schools 1. Vocational School of Medical Sciences 2. Vocational School -

Tuzla Müftülüğü 2016 Yili Ramazan Ayinda Mukabele Okunanan Camiler Ve Mukabele Okuma Vakitleri Mukabele Okuma C a M I N I N Vakitleri

TUZLA MÜFTÜLÜĞÜ 2016 YILI RAMAZAN AYINDA MUKABELE OKUNANAN CAMİLER VE MUKABELE OKUMA VAKİTLERİ MUKABELE OKUMA C A M İ N İ N VAKİTLERİ S.NO İLÇESİ ADI ADRESİ SABAH ÖĞLEDEN ÖNCE ÖĞLEDEN SONRA İKİNDİDE N ÖNCE İKİNDİDE N SONRA 1 TUZLA ABDULLAH PEHLİVANLI C. POSTANE MAHALLESİ KILIÇ CADDESİ NO:6 TUZLA İSTANBUL X 2 TUZLA AKFIRAT KİRAZLI MH. BEHİCE ÇİZMECİ C. TEPEÖREN MAHALLESİ KİRAZLI CADDE ERTUĞRUL SOKAK NO:7 TUZLA İSTANBUL X X 3 TUZLA AKFIRAT MERKEZ C. AKFIRAT MAHALLESİ AKFIRAT CADDESİ 16. SOKAK NO:5 TUZLA İSTANBUL X 4 TUZLA AKFIRAT MH.ŞİFA C. AKFIRAT MAHALLESİ FIRAT CADDESİ TUZLA İSTANBUL X 5 TUZLA AYDINLI EBUBEKİR C. AYDINLI MAHALLESİ SÜHEYLA SOKAK NO 100 TUZLA İSTANBU X 6 TUZLA AYDINLI MH.DERİ SANAYİ C. ORHANLI MAHALLESİ ORGANİZE DERİ SANAYİ BÖLGESİ KAZLI ÇEŞME CADDESİ 1.YOL TUZLA İSTANBUL X 7 TUZLA AYDINLI MH.HACILAR C. AYDINLI MAHALLESİ AYÇİÇEĞİ SOKAK NO:19 TUZLA İSTANBUL X 8 TUZLA AYDINLI MH.HÜDA C. AYDINLI MAHALLESİ DERSAADET CADDESİ AKTAR SOKAK NO:10 TUZLA İSTANBUL X 9 TUZLA AYDINLI MH.YUNUSEMRE C. AYDINLI MAHALLESİ TOKİ EVLERİ 2. ETAP BURÇAK SOKAK TUZLA İSTANBUL X 10 TUZLA AYDINLI YILDIZ C. AYDINLI MAHALLESİ GÜLEN SOKAK TUZLA / İSTANBUL X 11 TUZLA AYDINTEPE MERKEZ C. AYDINTEPE MAHALLESİ DOSTLAROĞLU SOKAK NO 12 TUZLA İSTANBUL X 12 TUZLA AYDINTEPE MH.YEŞİLDERE MERKEZ C. AYDINTEPE MAHALLESİ YAVUZ CADDESİ ŞEHİT MURAT MATUZ SOKAK NO:2 TUZLA İSTANBUL X 13 TUZLA BİRMES SANAYİ SİTESİ MESCİDİ SS.BİRMES TOPLU İŞYERİ YAPI KOOP.ORHANLI MERKEZ MAH.ATATÜRK CAD.9 TUZLA İSTANBUL X 14 TUZLA ELİYA ÇELEBİ MH.HZ.ÖMER C. -

SS1 for Ebook

Hot Plasma on the Rocks IF ONLY Hot Plasma on the Rocks Another Chance the lesson Another Chance A Brush with the Dark Side The Perfect Gift A Brush with the Dark Side In Control Roland Fish Rises up In Control Waiting in the Wings There’s Nothing Like a Good Book Waiting in the Wings The Main Event Hot Plasma on the Rocks The Main Event Going Ballistic Another Chance Going Ballistic IF ONLY A Brush with the Dark Side IF ONLY the lesson In Control the lesson The Perfect Gift Waiting in the Wings The Perfect Gift Roland Fish Rises up The Main Event Roland Fish Rises up There’s Nothing Like a GoodSTORIES Book Going Ballistic There’s 1 Nothing Like a Good Book STORIESIF ONLY 1 Hot Plasma on theSHORT Rocks Hot Plasma on the Rocks Another ChanceSHORT the lesson The Perfect Gift Another Chance A Brush with the Dark Side A Brush with the Dark Side In ControlREADINGRoland AGES Fish 10 Rises - 16 up YEARSIn Control Waiting in the Wings There’s Nothing Like a Good Book Waiting in the Wings The Main Event HotAnother Plasma on Chance the Rocks The Main Event GoingIF ONLY Ballistic GoingIF ONLY Ballistic the lesson A Brush with the Dark Side the lesson The Perfect Gift In Control The Perfect Gift Waiting in the Wings Roland Fish Rises up The Main Event Roland Fish Rises up There’s Nothing Like a Good Book Going Ballistic There’s Nothing Like a Good Book Hot Plasma on the Rocks IF ONLY Hot Plasma on the Rocks Another Chance the lesson Another Chance A Brush with the Dark Side The Perfect Gift A Brush with the Dark Side In Control Roland Fish Rises up -

Magazine Over the Past Year, Especially Our Regular Contributors! We Look Forward to All Your Future Articles

VIEWLANDS REVIEW - Issue 70 Summer 2019 Hello everyone, The Annexe is open to use at last! We will have an official opening later in the year. Residents enjoyed afternoon tea there recently and admired the building. Art class sessions are taking place there. Several meeting and training sessions have also taken place. Please feel free to give us suggestions on what you want to use this facility for. Games afternoons have been suggested. We will be having a Summer Fair on the 24th August organised by the Friends of Viewlands to raise funds for activities for residents. These funds are used to pay for things like the bus for outings, ice-creams and for concerts in the House. We normally have a lovely afternoon with stalls and afternoon tea. An unannounced inspection was carried out by the Care Inspectorate at Viewlands house on the 16th and 17th July. The final Inspection Report has still to be published – it will be put on the noticeboard when received. We have been awarded grade five (very good) for ‘How well do we support people’s wellbeing?’ and grade 4 (good) for ‘How well is our care and support planned? Going forward the company is looking at using a digital system for care planning. Stan has gone home to the Czech Republic but says he will keep in touch with us. Carl has started as maintenance person and is fitting in well. We also welcomed Kenny, chef, he is also fitting in well to our staff team as Alan left to run his own business. -

Aproximações Entre O Cinema De Fatih Akin E O Neuer Deutscher Film De Três Décadas Atrás

Revista Contingentia | Gabriela Wondracek Linck “Eine Kneipe ist wie ein Film” - Aproximações entre o cinema de Fatih Akin e o Neuer Deutscher Film de três décadas atrás Gabriela Wondracek Linck recebido em 19/09/2010 e aceito em 21/10/2010 Fatih Akin has been the subject of much research in the academic world, especially regarding his portrayal of young Turkish Germans, Turkey and the borders between Europe and the Middle East. This article presents a critical evaluation of these approaches and then looks into Akin’s relation with music, literature and the New German Cinema from the 1970’s and 80’s. Keywords: Fatih Akin; Rainer Werner Fassbinder; Wim Wenders Literature; Jasmin Ramadan; Germany; Media; Cinema; Music. “Lar é onde nascemos e não onde nossos pais nasceram” Fatih Akin. 1 1 Introdução Neste artigo, pretendo apresentar o cineasta “turco-alemão” Fatih Akin como representante das tendências do cinema alemão contemporâneo. Considero os filmes de Fatih Akin em comparação ao cinema da Alemanha surgido a partir do Manifesto de Oberhausen, que em 1966 inaugurou o Neuer Deutscher Film, apregoando “a morte do cinema do papai” (Papas Kino ist Tot). Partindo da afirmação de Fatih Akin de que o filme Contra a Parede (2004) seria o seu equivalente ao filme O Medo Devora a Alma (Fassbinder, 1974) - por analogia, seu Neuer Deutscher Film - e que Soul Kitchen (2009) seria seu Heimat Film - bem como outras referenciações do diretor ao representante do Cinema Novo Alemão Rainer Werner Fassbinder - serão aqui brevemente esmiuçadas as proximidades entre os temas e a prática fílmica dos dois diretores. -

Copyright by Berna Gueneli 2011

Copyright by Berna Gueneli 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Berna Gueneli Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CHALLENGING EUROPEAN BORDERS: FATIH AKIN’S FILMIC VISIONS OF EUROPE Committee: Sabine Hake, Supervisor Katherine Arens Philip Broadbent Hans-Bernhard Moeller Pascale Bos Jennifer Fuller CHALLENGING EUROPEAN BORDERS: FATIH AKIN’S FILMIC VISIONS OF EUROPE by Berna Gueneli, B.A., M.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication For my parents Mustafa and Günay Güneli and my siblings Ali and Nur. Acknowledgements Scholarly work in general and the writing of a dissertation in particular can be an extremely solitary endeavor, yet, this dissertation could not have been written without the endless support of the many wonderful people I was fortunate to have in my surroundings. First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation advisor Sabine Hake. This project could not have been realized without the wisdom, patience, support, and encouragement I received from her, or without the intellectual exchanges we have had throughout my graduate student life in general and during the dissertation writing process in particular. Furthermore, I would like to thank Philip Broadbent for discussing ideas for this project with me. I am grateful to him and to all my committee members for their thorough comments and helpful feedback. I would also like to extend my thanks to my many academic mentors here at the University of Texas who have continuously guided me throughout my intellectual journey in graduate school through inspiring scholarly questions, discussing ideas, and encouraging my intellectual quest within the field of Germanic and Media Studies. -

Uction of Ordinance to Force Clearing of Lots Is Approved

-......... ---~- . ~' UCTION OF ORDINANCE TO FORCE CLEARING OF LOTS IS APPROVED 0>-------- upport Your Favorite Baby THENE KPOST In Cont.e t ~ -------------~ School R egi s tration The Newark Board of Edu SWIMMING Active On "Dollar Days" Committee cotion has issued a second no MERCHANTS NEW LOCAL tice to paren ts and guardians relative to the registration of COSTS ARE I children for entrance in local SATISFIED LAW HOLDS public schools in September. Early regist.ration is being PONDERED urged. WITH SALE $10 FINE It is particularly important, states the notice, that children Pool Committee entering the first grade be reg PilDick Holds AS THREAT istered without delay so that Faces Deficit; school officials can complete "Returns Good" arrangements for handling Donations Down Packing Plant new students. Following Event It is necessary for all pupils . T~e problem of finances, embrac- Following a survey of Main Street To Cooperate; who have not attended pubUc mg mcome and operating expenses, business houses that participated in schools in Newark to register was the principal item discussed at the Tuesday and Wednesday "Dollar Council Meets before entering. This rule ap- a special meeting of the Newark Days" sales event, Meyer Pilnick, plies in particular to children Swimming Pool Committee Tuesday chairman of the mercantile section In "Darkness" who have just become of evening. The session was held at of the Chamber of Commerce, which The Council of Newark at the Au- school age and to children the residence of Dr. J. S. Gould, sponsored the affair, expressed satis- gust session Monday night voiced who have I' e c e n t I y been president of the Newark P arent- faction this morning on the part of unanimous approval to the first and brought to Newark, but have Teacher Association and chairman participants and buyers in kind. -

Soul Kitchen

presenta Soul Kitchen un film di Fatih Akin uscita 8 gennaio durata 99 minuti www.soulkitchen-ilfilm.it ufficio stampa Federica de Sanctis 335.1548137 [email protected] Con il supporto del Programma MEDIA dell’Unione Europea BIM DISTRIBUZIONE Via Marianna Dionigi 57 00193 ROMA Tel. 06-3231057 Fax 06-3211984 www.bimfilm.com SOUL KITCHEN un film di Fatih Akin con Adam Bousdoukos, Moritz Bleibtreu, Birol Ünel, Pheline Roggan, Anna Bederke, Dorka Gryllus, Lucas Gregorowicz, Wotan Wilke Möhring e altri! LA VITA È QUELLO CHE TI SUCCEDE MENTRE SEI IMPEGNATO A FARE ALTRI PROGETTI (John Lennon) SOUL KITCHEN parla di famiglia e di amici, di amore, di fiducia e di lealtà e della lotta per proteggere un luogo chiamato casa in un mondo sempre più imprevedibile. Per raccontare questa storia Fatih Akin ha radunato i migliori attori dei suoi film precedenti - Adam Bousdoukos (KURZ UND SCHMERZLOS, LA SPOSA TURCA), Moritz Bleibtreu (SOLINO, IM JULI), Birol Ünel (LA SPOSA TURCA, IM JULI). la storia Zinos, giovane proprietario del ristorante “Soul Kitchen”, sta attraversando un periodo sfortunato. Nadine, la sua ragazza, si è trasferita a Shanghai, i suoi clienti abituali boicottano il nuovo chef e ha problemi alla schiena! La situazione sembra migliorare quando un giro giusto di persone abbraccia la sua nuova filosofia culinaria, ma non basta a guarire il cuore spezzato di Zinos. Decide di volare in Cina per raggiungere Nadine, consegnando il ristorante all'inaffidabile fratello Illias, un ex detenuto. Entrambe le decisioni si riveleranno catastrofiche: Illias si gioca il ristorante che finisce nelle mani di un losco agente immobiliare e Nadine si è trovata un nuovo amante! Ma, forse, i fratelli Zinos e Illias hanno un'ultima possibilità di riprendersi il Soul Kitchen, sempre che riescano a smettere di litigare e si decidano a fare un gioco di squadra.