Elgar Tying and Exclusive Dealing Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifying Monopolists' Illegal Conduct Under the Sherman Act

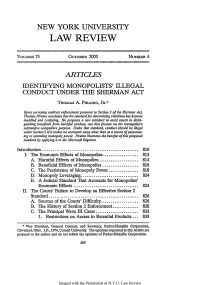

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 75 OCTOBER 2000 NUMBER 4 ARTICLES IDENTIFYING MONOPOLISTS' ILLEGAL CONDUCT UNDER THE SHERMAN ACT THOMAS A. Pmnn'io, JR.' Upon surveying antitrust enforcement pursuant to Section 2 of the Sherman Act, Thomas Pirainoconcludes that the standardfor determining violations has become muddled and confusing. He proposes a new standard to assist courts in distin- guishing beneficial from harmfid conduc; one that focuses on the monopolist's substantive competitive purpose. Under that standard, conduct should be illegal under Section 2 if it makes no economic sense other than as a means of perpetuat- ing or extending monopoly power. Pirainoillustrates the benefits of this proposed standard by applying it to the Microsoft litigation. Introduction .................................................... 810 I. The Economic Effects of Monopolies ................... 813 A. Harmful Effects of Monopolies ..................... 814 B. Beneficial Effects of Monopolies ................... 816 C. The Persistence of Monopoly Power ................ 818 D. Monopoly Leveraging ............................... 824 E. A Judicial Standard That Accounts for Monopolies' Economic Effects ................................... 824 II. The Courts' Failure to Develop an Effective Section 2 Standard ................................................ 826 A. Sources of the Courts' Difficulty .................... 826 B. The History of Section 2 Enforcement .............. 828 C. The Principal Wave III Cases ....................... 833 1. Restrictions on Access to Essential Products ... 833 * Vice President, General Counsel, and Secretary, Parker-Hannifin Corporation, Cleveland, Ohio. J.D., 1974, Cornell University. The opinions expressed in this Article are personal to the author and do not reflect the opinions of Parker-Hannifin Corporation. 809 Imaged with the Permission of N.Y.U. Law Review NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 75:809 2. Tying and Exclusive Dealing Arrangements ... -

A Comprehensive Economic and Legal Analysis of Tying Arrangements

A Comprehensive Economic and Legal Analysis of Tying Arrangements Guy Sagi* I. INTRODUCTION The law of tying arrangements as it stands does not correspond with modern economic analysis. Therefore, and because tying arrangements are so widely common, the law is expected to change and extensive aca- demic writing is currently attempting to guide its way. In tying arrangements, monopolistic firms coerce consumers to buy additional products or services beyond what they intended to purchase.1 This pressure can be applied because a consumer in a monopolistic mar- ket does not have the alternative to buy the product or service from a competing firm. In the absence of such choice, the monopolistic firm can allegedly force the additional purchase on the consumer at non-beneficial terms. The “tying product” is the one the consumer wants to buy, and the product the firm attaches to the tying product is termed the “tied prod- 2 uct.” * Lecturer, Netanya Academic College; Adjunct Lecturer, The Hebrew University School of Law; LL.B., The Hebrew University School of Law; LL.M. and J.S.D. Columbia University School of Law. 1. In a competitive market, consumers can choose to buy from firms that do not tie products, as opposed to ones that do. The tying firm, in such a case, would then lose out. At the same time, it is possible that in a competitive market, some products would still be offered together because it would be beneficial to both producers and consumers. 2. It can sometimes be difficult to differentiate between the tying of two separate products and the sale of two components forming a single whole product. -

Competition and Monopoly : Single-Firm Conduct Under Section

CHAPTER 8 EXCLUSIVE DEALING I. Introduction prohibiting one party from dealing with 5 Exclusive dealing describes an arrangement others, or the exclusive-dealing arrangement whereby one party’s willingness to deal with can take other forms, as when a seller enacts another is contingent upon that other party (1) policies effectively requiring customers to deal dealing with it exclusively or (2) purchasing a exclusively with it. large share of its requirements from it.1 Exclusive dealing is frequently procom- Exclusive dealing is common and can take petitive, as when it enables manufacturers and many forms.2 It often requires a buyer to deal retailers to overcome free-rider issues exclusively with a seller. For example, a misaligning the incentives for these vertically- manufacturer may agree to deal with a related firms to satisfy the demands of distributor only if the distributor agrees not to consumers most efficiently. For example, a carry the products of the manufacturer’s manufacturer may be unwilling to train its competitors.3 And many franchise outlets agree distributors optimally if distributors can take to buy certain products exclusively from a that training and use it to sell products of the franchisor.4 But it also may involve a seller manufacturer’s rivals. Other benefits can occur dealing exclusively with a single buyer. as well, as when an exclusivity arrangement assures a customer of a steady stream of a Exclusive dealing also occurs between necessary input. sellers and consumers, as when a consumer agrees to purchase all its requirements of a But exclusive dealing also can be particular product from a single supplier. -

A Proposal to Enhance Antitrust Protection Against Labor Market Monopsony Roosevelt Institute Working Paper

A Proposal to Enhance Antitrust Protection Against Labor Market Monopsony Roosevelt Institute Working Paper Ioana Marinescu, University of Pennsylvania Eric A. Posner, University of Chicago1 December 21, 2018 1 We thank Daniel Small, Marshall Steinbaum, David Steinberg, and Nancy Walker and her staff, for helpful comments. 1 The United States has a labor monopsony problem. A labor monopsony exists when lack of competition in the labor market enables employers to suppress the wages of their workers. Labor monopsony harms the economy: the low wages force workers out of the workforce, suppressing economic growth. Labor monopsony harms workers, whose wages and employment opportunities are reduced. Because monopsonists can artificially restrict labor mobility, monopsony can block entry into markets, and harm companies who need to hire workers. The labor monopsony problem urgently calls for a solution. Legal tools are already in place to help combat monopsony. The antitrust laws prohibit employers from colluding to suppress wages, and from deliberately creating monopsonies through mergers and other anticompetitive actions.2 In recent years, the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department have awoken from their Rip Van Winkle labor- monopsony slumber, and brought antitrust cases against employers and issued guidance and warnings.3 But the antitrust laws have rarely been used by private litigants because of certain practical and doctrinal weaknesses. And when they have been used—whether by private litigants or by the government—they have been used against only the most obvious forms of anticompetitive conduct, like no-poaching agreements. There has been virtually no enforcement against abuses of monopsony power more generally. -

Reconciling the Harvard and Chicago Schools: a New Antitrust Approach for the 21St Century

Indiana Law Journal Volume 82 Issue 2 Article 4 Spring 2007 Reconciling the Harvard and Chicago Schools: A New Antitrust Approach for the 21st Century Thomas A. Piraino Jr. Parker-Hannifin Corporation Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons Recommended Citation Piraino, Thomas A. Jr. (2007) "Reconciling the Harvard and Chicago Schools: A New Antitrust Approach for the 21st Century," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 82 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol82/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reconciling the Harvard and Chicago Schools: A New Antitrust Approach for the 21st Century THOMAS A. PIRAINO, JR.* INTRODUCTION: A NEW APPROACH TO ANTITRUST ANALYSIS ............................... 346 I. THE BATTLE FOR THE SOUL OF ANTITRUST .................................................. 348 A . The Harvard School ........................................................................... 348 B. The Chicago School ........................................................................... 350 II. THE PRINCIPAL CASES REFLECTING THE HARVARD/CHICAGO SCHOOL C ON FLICT .................................................................................................... -

Recent Development of Indonesian Competition Law and Agency

The Contribution of Competition Policy to Improving Regulatory Performance Ahmad Junaidi Bureau of Policy 1 Indonesia Competition Law • Competition is regulated by The Law No.5 Year 1999 Concerning Prohibition on Monopolistic Practices and Unfair Business Practices • The Law has been implemented for almost 11 year to enhance fair competition, since Indonesia economic policy and structure changes after crisis 1998. 2 PRINCIPLES AND PURPOSES The Principle (Article 2) Business activities of business actors in Indonesia must be based on economic democracy, with due observance of the equilibrium between the interests of business actors and the interests of the public The Purposes (Article 3) The purpose of enacting this Law shall be as follows: a. to safeguard the interests of the public and to improve national economic efficiency as one of the efforts to improve the people’s welfare; b. to create a conducive business climate through the stipulation of fair business competition in order to ensure the certainty of equal business opportunities for large-, middle- as well as small-scale business actors in Indonesia c. to prevent monopolistic practices and or unfair business competition that may be committed by business actors; and d. the creation of effectiveness and efficiency in business activities. 3 Structure of The Law Prohibited Agreements: Prohibited Dominant (rule of reason’s approach) Activities Position: (rule of reason’s (rule of reason’s Agreement with Foreigner approach) approach) Exclusive Dealing Monopoly Dominant Oligopsony Monopsony Position Trusts Share Ownership Vertical Intregation Market Control Cartel Conspiracy Interlocking Boycott Merger and Oligopoly Acquition Price Fixing 4 The Commission: KPPU • The Commission for the Supervision of Business Competition (KPPU) was established in 2000 with the authority mandated by the Law No. -

Exclusive Dealing: Before, Bork, and Beyond

Exclusive Dealing: Before, Bork, and Beyond The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation J. Mark Ramseyer & Eric B. Rasmusen, Exclusive Dealing: Before, Bork, and Beyond, 57 J. L. & Econ. S145 (2014). Published Version http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/680347;10.1086/680347 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:16952765 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 1 October 6, 2013 Address correspondence to: [email protected] [email protected] Goal: 5000-7500 words Currently: 6,465 words (including everything) Exclusive Dealing: Before Bork, and Beyond J. Mark Ramseyer and Eric B. Rasmusen* Abstract: Antitrust scholars have come to accept the basic ideas about exclusive dealing that Bork articulated in The Antitrust Paradox. Indeed, they have even extended his list of reasons why exclusive dealing can promote economic efficiency. Yet they have also taken up his challenge to explain how exclusive dealing could possibly cause harm, and have modelled a variety of special cases where it does. Some (albeit not all) of these are sufficiently plausible to be useful to prosecutors and judges. *J. Mark Ramseyer, Mitsubishi Professor, Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, 617-496-4878; Eric B. Rasmusen, Dan R. and Catherine M. Dalton Professor, Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 47405-1701, [email protected], 812-855-9219. -

The Use of Tying Requirements in Patent Licensing

Marquette University Law School Marquette Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1981 The seU of Tying Requirements in Patent Licensing Ramon A. Klitzke Marquette University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/facpub Part of the Law Commons Publication Information Ramon A. Klitzke, The sU e of Tying Requirements in Patent Licensing, 9 APLA Q.J. 333 (1981) Copyright, 1982, Ramon A. Klitzke Repository Citation Klitzke, Ramon A., "The sU e of Tying Requirements in Patent Licensing" (1981). Faculty Publications. Paper 539. http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/facpub/539 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TYING THE USE OF TYING REQUIREMENTS IN PATENT LICENSING BY RAMON A. KLITZKE* Tying is the sale or license of an item (the tying item) upon the condition that another item (the tied item) be purchased. When the tying item pos- sesses sufficient economic power, "to appreciably restrain free competition in the market for the tied product,"I the antitrust laws are violated. The requisite power is presumed when the tying product is patented or copy- righted.2 To tie a product or service to a patent therefore violates the anti- trust laws. The major patent tying cases will be examined in this article. The features of tying arrangements that are either violations of the antitrust statutes or pat- ent misuse will be sketched. -

Some Canadian Thoughts on Exclusive Dealing

Some Canadian Thoughts on Exclusive Dealing ICN Unilateral Conduct Working Group Teleseminar July 17, 2012 James Musgrove McMillan LLP with assistance from Devin Anderson Document # 6003961 LEGISLATION A. Section 77(1): For the purposes of this section, “exclusive dealing” means (a) any practice whereby a supplier of a product, as a condition of supplying the product to a customer, requires that customer to (i) deal only or primarily in products supplied by or designated by the supplier or the supplier’s nominee, or (ii) refrain from dealing in a specified class or kind of product except as supplied by the supplier or the nominee, and (b) any practice whereby a supplier of a product induces a customer to meet a condition set out in subparagraph (a)(i) or (ii) by offering to supply the product to the customer on more favourable terms or conditions if the customer agrees to meet the condition set out in either of those subparagraphs; 2 LEGISLATION B. Section 77(2): Where … the Tribunal finds that exclusive dealing ... because it is engaged in by a major supplier of a product in a market or because it is widespread in a market, is likely to (a) impede entry into or expansion of a firm in a market, (b) impede introduction of a product into or expansion of sales of a product in a market, or (c) have any other exclusionary effect in a market, with the result that competition is or is likely to be lessened substantially, the Tribunal may make an order directed to all or any of the suppliers against whom an order is sought prohibiting them from continuing to engage in that exclusive dealing … and containing any other requirement that, in its opinion, is necessary to overcome the effects thereof in the market or to restore or stimulate competition in the market. -

Tying and Consumer Harm Daniel A

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2012 Tying and Consumer Harm Daniel A. Crane University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/1374 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Communications Law Commons, and the Consumer Protection Law Commons Recommended Citation Crane, Daniel A. "Tying and Consumer Harm." Competition Pol'y. Int'l. 8, no. 2 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 8 | Number 2 | Autumn 2012 Tying and Consumer Harm Daniel Crane University of Michigan Law School Tying and Consumer Harm 27 TYING AND CONSUMER HARM Daniel Crane* ABSTRACT: Brantley raises important issues of law, economics, and policy about tying arrangements. Under current legal principles, Brantley was on solid ground in distinguishing between anticompetitive ties and those that might harm consumer interests without impairing competition. As a mat- ter of economics, the court was also right to reject the claim that the cable programmers forced consumers to pay for programs the customers didn’t want. The hardest question is a policy one - whether antitrust law should ever condemn the exploitation of market power in ways that extract surplus from consumers but do not create or enlarge market power. -

Exclusive Dealing and Competition: a US FTC View Alden F

Exclusive Dealing and Competition: A US FTC View Alden F. Abbott General Counsel, U.S. Federal Trade Commission ICN Workshop, Stellenbosch, South Africa, November 2, 2018 1 Introduction: Exclusive Dealing Basics • “An exclusive dealing contract is a contract under which a buyer promises to buy its requirements of one or more products exclusively from a particular seller.” Hovenkamp, Federal Antitrust Policy (2016) • Variations on “full scale” exclusive dealing (partial, de facto) • Loyalty discounts, discounts tied to percentage of purchases from a seller • Slotting allowances, supplier pays fee for preferred or exclusive shelf space • Requirements contracts, agreements to buy all needed units from one seller, also de facto agreements under which firms won’t buy from other sellers • Exclusive dealing may confer substantial procompetitive benefits but also may pose significant anticompetitive risks • case-specific analysis is key • Exclusive dealing assessed by most authorities under antitrust “rule of reason” 2 Evaluating Exclusive Dealing – ICN Review • 2013 ICN Unilateral Conduct Workbook, Chapter 5 – Exclusive Dealing • Outlines elements for flexible rule of reason analysis, focus on evidence • Potential exclusive dealing efficiencies include: • Encouraging distributors to promote a manufacturer’s products more vigorously • Encouraging suppliers to help distributors by providing key services of information • Addressing problems of free riding between suppliers • Addressing “hold up” problems for customer-specific investments • Allowing suppliers to control distribution quality more easily • Potential harms related to market foreclosure (including raising rivals’ costs) • Price increases due to output reduction, also overall reduction in market output • Increase in dominant firm’s market share unexplainable by quality, supply/demand • Exit of existing competitors due to an exclusive dealing arrangement • Entry deterrence (preventing deterrence by potential competitors) 3 Evaluating Exclusive Dealing – U.S. -

Exclusive Contracts and Market Dominance!

Exclusive contracts and market dominance Giacomo Calzolari University of Bologna and CEPR Vincenzo Denicolò University of Leicester, University of Bologna and CEPR November 7th, 2014 Abstract We propose a new theory of exclusive dealing. The theory is based on the assumption that a dominant …rm has a competitive advantage over its rivals, and that the buyers’willingness to pay for the product is private information. In this setting, we show that the dominant …rm can impose contractual restrictions on buyers without having to compensate them. This implies that exclusive dealing contracts can be both pro…table and anticompetitive. We discuss the general implications of the theory for competition policy and illustrate by example how it applies to real world antitrust cases. Keywords: Exclusive dealing; Non-linear pricing; Antitrust; Dominant …rm J.E.L. numbers: D42, D82, L42 We thank Glenn Ellison, Paolo Ramezzana, Helen Weeds, Chris Wallace, Mike Whinston, Piercarlo Zanchettin and seminar participants at MIT, Boston University, Essex, Leicester, Stavanger, Pittsburgh, Bocconi, University of Washington, CEMFI, the Economics of Con‡ict and Cooperation workshop at Bergamo, the SAET conference in Paris, the IIOC conference in Chicago, the CEPR applied industrial organization conference in Athens, the US DoJ, and the European Commission (DG Comp) for useful discussion and comments. The usual disclaimer apply. 1 1 Introduction Exclusive dealing contracts have long raised antitrust concerns. However, ex- isting anticompetitive theories rely on assumptions that do not always …t real antitrust cases. In this paper, we propose a new theory of competitive harm, which is arguably more broadly applicable than existing ones.