A Conversation with Bill Withers by Bill Demain (Puremusic.Com, 9/2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biu Withers by Rob Bowman He Was the Leading Figure in the Nascent Black Singer-Songwriter Movement of the Early 1970S

PERFORMERS BiU Withers By Rob Bowman He was the leading figure in the nascent black singer-songwriter movement of the early 1970s. BILL WITHERS WAS SIMPLY NOT BORN TO PLAY THE record industry game. His oft-repeated descriptor for A&R men is “antagonistic and redundant.” Not surprisingly, most A&R men at Columbia Records, the label he recorded for beginning in 1975, considered him “difficult.” Yet when given the freedom to follow his muse, Withers wrote, sang, and in many cases produced some of our most enduring classics, including “Ain’t No Sunshine,” “Lean on Me,” “Use Me,” “Lovely Day,” “Grandma’s Hands,” and “Who Is He (and What Is He to You).” ^ “Not a lot of people got me,” Withers recently mused. “Here I was, this black guy playing an acoustic guitar, and I wasn’t playing the gut-bucket blues. People had a certain slot that they expected you to fit in to.” ^ Withers’ story is about as improb able as it could get. His first hit, “Ain’t No Sunshine,” recorded in 1971 when he was 33, broke nearly every pop music rule. Instead of writing words for a bridge, Withers audaciously repeated “I know” twenty-six times in a row. Moreover, the two-minute song had no introduction and was released as a throwaway B-side. Produced by Stax alumni Booker T. Jones for Sussex Records, the single’s struc ture, sound, and sentiment were completely unprecedented and pos sessed a melody and lyric that tapped into the Zeitgeist of the era. Like much of Withers’ work, it would ultimately prove to be timeless. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Title Artist Name SUNTAN CITY AARON PRITCHETT SAVE A

Title Artist Name SUNTAN CITY AARON PRITCHETT SAVE A HORSE, RIDE A COWBOY BIG & RICH GOD'S COUNTRY BLAKE SHELTON BOYS 'ROUND HERE BLAKE SHELTON ALL ABOUT TONIGHT BLAKE SHELTON HONEY BEE BLAKE SHELTON A GUY WITH A GIRL BLAKE SHELTON REMIND ME BRAD PAISLEY & CARRIE UNDERWOOD LOVE SOMEONE BRETT ELDREDGE CECILIA BRETT KISSEL SOUTHBOUND CARRIE UNDERWOOD CHURCH BELLS CARRIE UNDERWOOD BLOWN AWAY CARRIE UNDERWOOD DIRTY LAUNDRY CARRIE UNDERWOOD BUY ME A BOAT CHRIS JANSON RAISED ON COUNTRY CHRIS YOUNG Hangin' On Chris Young NOTHING BUT SUMMER DALLAS SMITH SKY STAYS THIS BLUE DALLAS SMITH ALL TO MYSELF DAN + SHAY SPEECHLESS DAN + SHAY TEQUILA DAN + SHAY Wagon Wheel Darius Rucker feat. Lady Antebellu EVERYTHING'S GONNA BE ALRIGHT DAVID LEE MURPHY FEAT. KENNY CHESNEY CANADIAN GIRLS DEAN BRODY TIME DEAN BRODY DRUNK ON A PLANE DIERKS BENTLEY SOMEWHERE ON A BEACH DIERKS BENTLEY BURNING MAN DIERKS BENTLEY F. BROTHERS OSBORN GOOD GIRL DUSTIN LYNCH SOME OF IT ERIC CHURCH DRINK IN MY HAND ERIC CHURCH SPRINGSTEEN ERIC CHURCH Simple Florida Georgia Line ROUND HERE FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE CRUISE FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE SUN DAZE FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE GET YOUR SHINE ON FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE This Is How We Roll Florida Georgia Line feat. Luke Bryan LETS LAY DOWN AND DANCE GARTH BROOKS SHE'S WITH ME HIGH VALLEY DOWN TO THE HONKYTONK JAKE OWEN I WAS JACK (YOU WERE DIANE) JAKE OWEN REARVIEW TOWN JASON ALDEAN GIRL LIKE YOU JASON ALDEAN LIGHTS COME ON JASON ALDEAN THEY DON'T KNOW JASON ALDEAN DIRT ROAD ANTHEM JASON ALDEAN NIGHT SHIFT JON PARDI DIRT ON MY BOOTS JON PARDI SOMEBODY ELSE WILL JUSTIN MOORE YOU LOOK LIKE I NEED A DRINK JUSTIN MOORE HEAVEN KANE BROWN WE WERE KEITH URBAN SOMEWHERE IN MY CAR KEITH URBAN SOMEBODY LIKE YOU KEITH URBAN KISS A GIRL KEITH URBAN WASTED TIME KEITH URBAN WHO WOULDN'T WANT TO BE ME KEITH URBAN YOU LOOK GOOD IN MY SHIRT KEITH URBAN Coming Home Keith Urban feat. -

Dream Shake Song List

Dream Shake Song List My Stupid Mouth – John Mayer Nature Boy – Nat King Cole Africa – D’angelo On & On – Erykah Badu Aint No Sunshine – Bill Withers One Mo Gin’ – D’angelo Back in the Day – Erykah Badu Ordinary People – John Legend Banana Pancakes – Jack Johnson Roses – Outkast Brown Sugar – D’angelo Save Room – John Legend City Love – John Mayer Senorita – Justin Timberlake Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Seven Nation Army – White Stripes (Ben l Oncle Cruisin’ – D’angelo Soul) Don’t Worry Be Happy – Bobby Mcferrin Sitting, Waiting, Wishing – Jack Johnson Easy Like Sunday Morning – Lionel Richie Slow Dancing – John Mayer Fallin’ – Alicia Keys Stay With You – John Legend Feel Like Making Love – Roberta Flack (D’angelo) Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Georgia On My Mind – Ray Charles Sunday Morning – Maroon 5 Get Lucky – Daft Punk Sunny – Bobby Hebb Got to Give it up – Marvin Gaye Super Rich Kids – Frank Ocean Gravity – John Mayer Taylor – Jack Johnson Hey Ya – Outkast Thinkin Bout You - Frank Ocean Hit the Road Jack – Ray Charles Vallery – Amy Winehouse I Need a Dollar – Aloe Black Waiting in Vain – Bob Marley I Shot the Sheriff – Bob Marley What’s Going On – Marvin Gaye Isn’t She Lovely – Stevie Wonder When We get By – D’angelo Just Friends – Musiq Soulchild Why Georgia – John Mayer Lazy Song – Bruno Mars Wonderful World – Louis Armstrong Lean On Me – Bill Withers Your Body is a Wonderland – John Mayer Lovely Day – Bill Withers And many more… Man’s World – James Brown Mercy Mercy Me – Marvin Gaye Ms. Jackson – Outkast . -

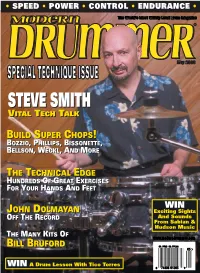

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

Keith Urban FAN TV

Presents KEITH URBAN Keith Lionel Urban (born October 26, 1967) is an Australian country music singer, songwriter and guitarist whose commercial success has been mainly in the United States and Australia. Urban was born in New Zealand and began his career in Brisbane having moved to Caboolture, Australia at an early age. In 1991, he released a self-titled debut album, and charted four singles in Australia before moving to the United States in 1992. Eventually, Urban found work as a session guitarist before starting a band known as The Ranch, which recorded one studio album on Capitol Records and charted two singles on the Billboard country charts. Still signed to Capitol, he made his solo American debut in 1999 with the album Keith Urban. Certified platinum in the U.S., it also produced his first American Number One in "But for the Grace of God". His breakthrough hit was the Number One "Somebody Like You", from his second Capitol album Golden Road (2002). This album also earned Urban his first Grammy Award win for "You'll Think of Me", its fourth single and the third Billboard Number One of his career. 2004's Be Here, his third American album, produced three more Number Ones, and became his highest-selling album, earning 4× Multi-Platinum certification. Love, Pain & the Whole Crazy Thing was released in 2006, producing the record-setting #17 country chart debut of "Once in a Lifetime", as well as Urban's second Grammy for the song "Stupid Boy", while a Greatest Hits package entitled Greatest Hits: 18 Kids followed in late 2007. -

Download This PDF File

Journal of Interdisciplinary Science Topics Lean on Me – Can Bill Withers stay true to his word? Jake Morris & Matt Perkins The Centre for Interdisciplinary Science, University of Leicester 27/03/2018 Abstract This paper aims to calculate the amount of force that Bill Withers would have to exert in order to support the people that have listened, or are listening to his song, Lean on Me, based upon the analytics from YouTube and Spotify. This will consider two scenarios: one in which everyone who has ever listened to his song leaned at him all at once, and another where all the concurrent listeners are leaning on him at any given time. These will be modelled through the use of component forces. The force that Bill Withers would have to exert when everyone leans on him at once, is calculated to equal 2.27×1010 N. The total force for the listeners at any given time is determined to be 19560 N. Introduction will be assumed that no sliding takes place. Bill The song Lean on Me was released in April 1972, by Withers is 1.87 m tall [4], and the average person’s the American singer songwriter Bill Withers [1]. In the height, representative of the constituents of the song Bill Withers sings “lean on me, when you’re not single mass being modelled, is 1.7 m tall [5]. If the strong”. This raises the question; what if everyone average head height, 23.9 cm [6] and neck length, that has listened, or is currently listening to the song 11 cm [7], for men, are taken away from Bill Withers’ took him up on his promise? This paper will height, the height that his shoulders are off the investigate the force Bill Withers would have to exert ground is found to be 1.52 m. -

Repertoire List

REPERTOIRE LIST Adele - Rolling in the Deep Jack Johnson - Better When We’re Together Outkast - Miss Jackson 90’S MEDLEY Alabama Shakes - Hold on Jackson 5 - ABC Outkast - Rosa Parks TLC Alicia Keys - Empire State of Mind James Brown - Get Up Oa That Thing Patrice Ruschen - Forget Me Nots Usher Alicia Keys - If I Ain’t Got You James and Bobby Purify - Shake A Tail Feather Percy Sledge - You Really Got a Hold On Me Montell Jordan Al Green - Let’s Stay Together James Blake - Limit To Your Love Pharrell – Happy Mark Morrison Al Green - Take Me to the River Jamie XX - Good Times Prince – I Wanna Be Your Lover Next Amy Whinehouse - Valerie Janelle Monae - Tightrope Prince - Kiss RIHANNA MEDLEY Beck – Where It’s At Jerry Lee Lewis - Great Balls of Fire Ray Charles - Georgia What’s My Name Beyonce – Crazy In Love Justin Timberlake - Can’t Stop The Feeling R Kelly - Remix to Ignition We Found Love Beyonce - Love on Top Justin Timberlake - Rock Your Body Sade - By Your Side Work Beyonce - Party Sade - Smooth Operator King Harvest - Dancing in the Moonlight MOTOWN MEDLEY Bill Withers - Ain’t No Sunshine Kendrick Lamar – If These Walls Could Talk Sade - Sweetest Taboo Your Love Keeps Lifting Me Higher and Higher Blondie – Rapture Leon Bridges - Coming Home Sam Cooke - Wonderful World You Really Got a Hold On Me Blood Orange - You’re Not Good Enough Lionel Richie - All Night Long Sam Cooke - Cupid Signed Sealed Delivered Bob Carlisle/Je Carson - Butterfly Kisses Little Richard - Good Golly Miss Molly Sam Cooke - Twistin’ Bruno Mars - 24k Magic Madonna -

Bill Withers Comes Back Into the Spotlight for Carnegie Hall Tribute (Downbeat.Com, 10/6/15)

Bill Withers Comes Back Into The Spotlight for Carnegie Hall Tribute (DownBeat.com, 10/6/15) Is there a happier refugee from the music business than singer-songwriter Bill Withers? The ex-Navy aircraft mechanic from dirt-poor Slab Fork, West Virginia, who got his first record contract in his thirties, was never a showbiz kid. He famously distrusted the business, keeping his day job as his first hit single, “Ain’t No Sunshine,” climbed the charts. Withers went on to write more hits, including the ubiquitous “Lean On Me.” By October 1972, a mere 15 months after he quit his day job, Withers was playing Carnegie Hall, a performance immortalized on the album Bill Withers Live at Carnegie Hall. Eventually he got disgusted with the record business, retired in 1985, and has lived contentedly at his home in the Hollywood Hills ever since, collecting a steady stream of royalties and, as he told Stephen Colbert recently, watching “Judge Judy.” This year has been very good to Withers. In April he was inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame. And on October 1, almost precisely 43 years to the day after his initial Carnegie Hall show, he was the subject of an all-star tribute concert at the same venue, a benefit for the Stuttering Association for Youth, or SAY (Withers stuttered until his mid-twenties). The concert producers, including City Winery’s Michael Dorf, assembled a parade of first-class R&B, pop and jazz talent to perform the Withers songbook, including Gregory Porter, Branford Marsalis, Ed Sheeran, Dr. -

Sensational Soul Cruisers Song List the Tramps

Sensational Soul Cruisers Song List The Tramps - Disco Inferno - Hold Back The Night KC and the Sunshine Band - Sound Your Funky Horn - Get Down Tonight - I‛m Your Boogie Man - Shake Your Booty - That‛s The Way I Like It - Baby Give It Up - Please Don‛t Go The Moments - Love On A Two Way Street The Bee Gees - You Should Be Dancin - Night Fever Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes - The Love I Lost - If You Don‛t Know Me By Now - Bad Luck - I Don‛t Love You Anymore The O‛Jays - Love Train - I Love Music - Back Stabbers - Used To Be My Girl The ChiLites - Have You Seen Her - Oh Girl Gladys Knight - The Best Thing That Ever Happened To Me - Midnight Train To Georgia Earth, Wind & Fire - September - Sing a Song - Shining Star - Let‛s Groove Main Ingredient - Everybody Plays The Fool Johnny Nash - I Can See Clearly Now Isley Brothers - Work To Do - It‛s Your Thing - Shout - Twist & Shout Tavares - It Only Takes a Minute - Free Ride - Heaven Must Be Missing an Angel - Don‛t Take Away The Music The Foundations - Now That I‛ve Found You Barry White - Can‛t Get Enough of You Babe - You‛re My First My Last My Everything - What Am I Gonna Do - Ecstasy (When You Lay Down Next To Me) Edwin Starr - 25 Miles The Platters - Only You Soul Survivors - Expressway Billy Ocean - Are You Ready George Benson - Turn Your Love Around Billy Ocean - Are You Ready Heat Wave - Boogie Nights - Always and Forever - Groove Line Bell & James - Livin It Up (Friday Night) Peter Brown - Dance With Me Jigsaw - Skyhigh Tyrone Davis - Turn Back the Hands of Time The Stylistics - -

Motwon/Disco/Soul/Funk

MOTWON/DISCO/SOUL/FUNK Ain’t No Mountain High Enough - Marvin Gaye Ain’t No Sunshine - Bill Withers Celebration - Kool & The Gang Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Easy Like Sunday Morning - The Commodores I Can See Clearly now - Johnny Nash Ladies Night-Kool & The Gang Let’s Get It On - Marvin Gaye Let’s Stay Together - Al Green Mustang Sally - Wilson Picket My Girl - The Temptations Proud Mary-Tina Turner September - Earth, Wind, & Fire Signed Sealed Delivered-Stevie Wonder Superstition - Stevie Wonder What’s Going On - Marvin Gaye 80s Africa - Toto All Night Long - Lionel Richie Call Me Al - Paul Simon Dancing In The Dark - Bruce Springsteen Don’t Stop Believing Journey Drive - The Cars Everybody Wants To Rule The World - Tears For Fears Footloose - Footloose Soundtrack Friday I’m In Love - The Cure Glory Days - Bruce Springsteen Head Over Heals - Tears For Fears How Soon Is Now - The Smiths Hungry Like The Wolf - Duran Duran Jack And Diane - John Cougar Just like Heaven - The Cure Living On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Love Song - The Cure New Sensation - INXS Pour Some Sugar On Me - Def Leppard Rosanna - Toto Sledgehammer - Peter Gabriel Still Haven’t Found What I'm Looking For - U2 Tempted - Squeeze This Charming Man - The Smiths What I Like About You - The Romantics Where The Streets Have No Name - U2 Wrapped Around Your Finger - The Police You Make My Dreams Come True - Hall & Oates CLASSIC ROCK American Girl - Tom Petty Bennie And The Jets - Elton John Black Magic Woman - Santana Born In The USA - Bruce Springsteen Born To Run - Bruce Springsteen -

Kevin's Solo Play List

Kevin’s Solo Play List 10cc - I'm Not In Love Ace - How Long (has this been going on) Al Green - Love & Happiness Al Green - Let's Stay Together Al Green - Take Me To The River Alan Parsons Project - Eye In The Sky Alan Parsons Project - Wouldn't Want To Be Like You Alan Parsons Project - Games People Play Allman Brothers - Melissa Allman Brothers - One Way Out Allman Brothers - Statesboro Blues April Wine - Just Between You and Me Atlanta Rhythm Section - So Into You B.B. King - Thrill Is Gone Bad Company - Can't Get Enough Badfinger - No Matter What Ben E. King - Stand By Me Bill Withers - Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers - Lean On Me Billy Joel - Only The Good Die Young Billy Joel - Vienna Waits For You Billy Joel - Honesty Billy Joel - You May Be Right Billy Preston - Will It Go Round In Circles Blondie - The Tide Is High Bobby Caldwell - What You Won't Do For Love Bob Dylan - Knockin' On Heavens Door Bob Marley / Eric Clapton - I Shot The Sheriff Bob Seger - Night Moves Bob Seger - Turn The Page Bob Seger - Against The Wind Boz Skaggs - Lowdown Bruce Springsteen - Fire Bruce Springsteen - Hungry Heart CCR - Down On The Corner CCR - Long As I Can See The Light Cream - Crossroads Cream - Sunshine Of Your Love Crosby Stills Nash - Love The One You're With Crowded House - Something So Strong Delbert McClinton - Givin' It Up For Your Love Delbert McClinton - Shakey Ground Duran Duran - Come Undone Earth Wind & Fire - Shining Star Earth Wind & Fire - Sing A Song Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood Eddie Money - Baby Hold On Elvis Presley - I Can't