Pas De Deux Between Dance and Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

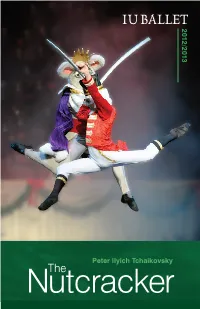

Nutcracker Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season ______Indiana University Ballet Theater Presents

2012/2013 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky NutcrackerThe Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents its 54th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann Michael Vernon, Choreography Andrea Quinn, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Patrick Mero, Lighting Designer Gregory J. Geehern, Chorus Master The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Thirtieth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December First, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December First, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Second, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Doricha Sales, Children’s Ballet Mistress The children in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music’s Pre-College Ballet Program. Act I Party Scene (In order of appearance) Urchins . Chloe Dekydtspotter and David Baumann Passersby . Emily Parker with Sophie Scheiber and Azro Akimoto (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Maura Bell with Eve Brooks and Simon Brooks (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Maids. .Bethany Green and Liara Lovett (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Carly Hammond and Melissa Meng (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Tradesperson . Shaina Rovenstine Herr Drosselmeyer . .Matthew Rusk (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Gregory Tyndall (Dec. 1 mat.) Iver Johnson (Dec. -

Doctor Atomic

John Adams Doctor Atomic CONDUCTOR Opera in two acts Alan Gilbert Libretto by Peter Sellars, PRODUCTION adapted from original sources Penny Woolcock Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm SET DESIGNER Julian Crouch COSTUME DESIGNER New Production Catherine Zuber LIGHTING DESIGNER Brian MacDevitt CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Doctor Atomic was made Andrew Dawson possible by a generous gift from Agnes Varis VIDEO DESIGN and Karl Leichtman. Leo Warner & Mark Grimmer for Fifty Nine Productions Ltd. SOUND DESIGNER Mark Grey GENERAL MANAGER The commission of Doctor Atomic and the original San Peter Gelb Francisco Opera production were made possible by a generous gift from Roberta Bialek. MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Doctor Atomic is a co-production with English National Opera. 2008–09 Season The 8th Metropolitan Opera performance of John Adams’s Doctor Atomic Conductor Alan Gilbert in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Edward Teller Richard Paul Fink J. Robert Oppenheimer Gerald Finley Robert Wilson Thomas Glenn Kitty Oppenheimer Sasha Cooke General Leslie Groves Eric Owens Frank Hubbard Earle Patriarco Captain James Nolan Roger Honeywell Pasqualita Meredith Arwady Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from the Neubauer Family Foundation. Additional support for this Live in HD transmission and subsequent broadcast on PBS is provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera Gerald Finley Chorus Master Donald Palumbo (foreground) as Musical Preparation Linda Hall, Howard Watkins, Caren Levine, J. -

Sex and Sin: the Magic of Red Shoes | Hilary Davidson

13. SEX AND SIN THE MAGIC OF RED SHOES1 hilary davidson The enduring potency of red shoes, both as real items of footwear and as sym- bol and cultural force, has fascinated people of different cultures in very diverse ways. The “power” of red shoes is not recent. The prestige of red heels in seven- teenth- and eighteenth-century European courts is well known. Subsequently, red shoes have taken on other charges. This chapter will focus on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale, The Red Shoes (1845).2 This literary work created symbolic associations which have become part of everyday cultural “usage” today. The power of Andersen’s fairy tale lies in its capacity to “dematerialize” red shoes by replacing their physicality with a symbolic meaning (Figure 13.1). This infusion of meaning into an object is a significant example of how dress and shoes are far from trivial and trivializing affairs. It established a template for the way in which red shoes were appreciated and comprehended in the twentieth century, especial- ly by women. 272 / HILARY DAVIDSON The understanding of red shoes proposed by Andersen was not just the result of a literary imagination. The writer was informed by precise ideas and concepts related to red footwear that had been developed in the period before he wrote his story. The peculiar psychological intensity of red shoes must also be further examined by considering Andersen’s life and personality. The Danish author’s neurotic self-obsession remained a constant feature of his literary production. Many of the features included in The Red Shoes have a psychological endurance in contemporary culture. -

The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance

Gordon 1 Jessica Gordon 29 March 2010 Honors Thesis Everything was Beautiful at the Ballet: The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance During the mid-1860s, a ballet troupe from Paris was brought to the Academy of Music in lower Manhattan. Before the company’s first performance, however, the theatre in which they were to dance was destroyed in a fire. Nearby, producer William Wheatley was preparing to begin performances of The Black Crook, a melodrama with music by Charles M. Barras. Seeing an opportunity, Wheatley conceived the idea to combine his play and the displaced dance company, mixing drama and spectacle on one stage. On September 12, 1866, The Black Crook opened at Niblo’s Gardens and was an immediate sensation. Wheatley had unknowingly created a new American art form that would become a tradition for years to come. Since the first performance of The Black Crook, dance has played an important role in musical theatre. From the dream ballet in Oklahoma to the “Dance at the Gym” in West Side Story to modern shows such as Movin’ Out, dance has helped tell stories and engage audiences throughout musical theatre history. Dance has not always been as integrated in musicals as it tends to be today. I plan to examine the moments in history during which the role of dance on the Broadway stage changed and how those changes affected the manner in which dance is used on stage today. Additionally, I will discuss the important choreographers who have helped develop the musical theatre dance styles and traditions. As previously mentioned, theatrical dance in America began with the integration of European classical ballet and American melodrama. -

Twyla Tharp Th Anniversary Tour

Friday, October 16, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 17, 2015, 8pm Sunday, October 18, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour r o d a n a f A n e v u R Daniel Baker, Ramona Kelley, Nicholas Coppula, and Eva Trapp in Preludes and Fugues Choreography by Twyla Tharp Costumes and Scenics by Santo Loquasto Lighting by James F. Ingalls The Company John Selya Rika Okamoto Matthew Dibble Ron Todorowski Daniel Baker Amy Ruggiero Ramona Kelley Nicholas Coppula Eva Trapp Savannah Lowery Reed Tankersley Kaitlyn Gilliland Eric Otto These performances are made possible, in part, by an Anonymous Patron Sponsor and by Patron Sponsors Lynn Feintech and Anthony Bernhardt, Rockridge Market Hall, and Gail and Daniel Rubinfeld. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PROGRAM Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour “Simply put, Preludes and Fugues is the world as it ought to be, Yowzie as it is. The Fanfares celebrate both.”—Twyla Tharp, 2015 PROGRAM First Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers The Practical Trumpet Society Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company Antiphonal Fanfare for the Great Hall by John Zorn. Used by arrangement with Hips Road. PAUSE Preludes and Fugues Dedicated to Richard Burke (Bay Area première) Choreography Twyla Tharp Music Johann Sebastian Bach Musical Performers David Korevaar and Angela Hewitt Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company The Well-Tempered Clavier : Volume 1 recorded by MSR Records; Volume 2 recorded by Hyperi on Records Ltd. INTERMISSION PLAYBILL PROGRAM Second Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers American Brass Quintet Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. -

Andersen's Fairy Tales

HTTPS://THEVIRTUALLIBRARY.ORG ANDERSEN’S FAIRY TALES H. C. Andersen Table of Contents 1. The Emperor’s New Clothes 2. The Swineherd 3. The Real Princess 4. The Shoes of Fortune 1. I. A Beginning 2. II. What Happened to the Councillor 3. III. The Watchman’s Adventure 4. IV. A Moment of Head Importance—an Evening’s “Dramatic Readings”—a Most Strange Journey 5. V. Metamorphosis of the Copying-clerk 6. VI. The Best That the Galoshes Gave 5. The Fir Tree 6. The Snow Queen 7. Second Story. a Little Boy and a Little Girl 8. Third Story. of the Flower-garden at the Old Woman’s Who Understood Witchcraft 9. Fourth Story. the Prince and Princess 10. Fifth Story. the Little Robber Maiden 11. Sixth Story. the Lapland Woman and the Finland Woman 12. Seventh Story. What Took Place in the Palace of the Snow Queen, and What Happened Afterward. 13. The Leap-frog 14. The Elderbush 15. The Bell 16. The Old House 17. The Happy Family 18. The Story of a Mother 19. The False Collar 20. The Shadow 21. The Little Match Girl 22. The Dream of Little Tuk 23. The Naughty Boy 24. The Red Shoes THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES Many years ago, there was an Emperor, who was so excessively fond of new clothes, that he spent all his money in dress. He did not trouble himself in the least about his soldiers; nor did he care to go either to the theatre or the chase, except for the opportunities then afforded him for displaying his new clothes. -

Twyla Tharp Goes Back to the Bones

HARVARD SQUARED ture” through enchanting light displays, The 109th Annual dramatizes the true story of six-time world decorations, and botanical forms. Kids are Christmas Carol Services champion boxer Emile Griffith, from his welcome; drinks and treats will be available. www.memorialchurch.harvard.edu early days in the Virgin Islands to the piv- (November 24-December 30) The oldest such services in the country otal Madison Square Garden face-off. feature the Harvard University Choir. (November 16- Decem ber 22) Harvard Wind Ensemble Memorial Church. (December 9 and 11) https://harvardwe.fas.harvard.edu FILM The student group performs its annual Hol- The Christmas Revels Harvard Film Archive iday Concert. Lowell Lecture Hall. www.revels.org www.hcl.harvard.edu/hfa (November 30) A Finnish epic poem, The Kalevala, guides “A On Performance, and Other Cultural Nordic Celebration of the Winter Sol- Rituals: Three Films By Valeska Grise- Harvard Glee Club and Radcliffe stice.” Sanders Theatre. (December 14-29) bach. The director is considered part of Choral Society the Berlin School, a contemporary move- www.harvardgleeclub.org THEATER ment focused on intimate realities of rela- The celebrated singers join forces for Huntington Theatre Company tionships. She is on campus as a visiting art- Christmas in First Church. First Church www.huntingtontheatre.org ist to present and discuss her work. in Cambridge. (December 7) Man in the Ring, by Michael Christofer, (November 17-19) STAFF PICK:Twyla Tharp Goes music of Billy Joel), and, in 2012, the ballet based on George MacDonald’s eponymous tale The Princess and the Goblin. Back to the Bones Yet “Minimalism and Me” takes the audience back to New York City in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and the emergence of a rigor- Renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp, Ar.D. -

MARK MORRIS DANCE GROUP and MUSIC ENSEMBLE Wed, Mar 30, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

2015 // 16 SEASON Northrop Presents MARK MORRIS DANCE GROUP AND MUSIC ENSEMBLE Wed, Mar 30, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage DIDO AND AENEAS Dear Friends of Northrop, Northrop at the University of Minnesota Presents I count myself lucky that I’ve been able to see a number of Mark Morris Dance Group’s performances over the years—a couple of them here at Northrop in the 90s, and many more in New York as far back as the 80s and as recently as last MARK MORRIS year. Aside from the shocking realization of how quickly time flies, I also realized that the reason I am so eager to see Mark Morris’ work is because it always leaves me with a feeling of DANCE GROUP joy and exhilaration. CHELSEA ACREE SAM BLACK DURELL R. COMEDY* RITA DONAHUE With a definite flair for the theatrical, and a marvelous ability DOMINGO ESTRADA, JR. LESLEY GARRISON LAUREN GRANT BRIAN LAWSON to tell a story through movement, Mark Morris has always AARON LOUX LAUREL LYNCH STACY MARTORANA DALLAS McMURRAY been able to make an audience laugh. While most refer to BRANDON RANDOLPH NICOLE SABELLA BILLY SMITH his “delicious wit,” others found his humor outrageous, and NOAH VINSON JENN WEDDEL MICHELLE YARD he earned a reputation as “the bad boy of modern dance.” *apprentice But, as New York Magazine points out, “Like Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, and Twyla Tharp, Morris has Christine Tschida. Photo by Patrick O'Leary, gone from insurgent to icon.” MARK MORRIS, conductor University of Minnesota. The journey probably started when he was eight years old, MMDG MUSIC ENSEMBLE saw a performance by José Greco, and decided to become a Spanish dancer. -

Helen Wagner Donald

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 1972 Programs 1972 9-19-1972 The Lion in inW ter starring Helen Wagner and Donald May Little Theatre on the Square Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/little_theatre_1972_programs Part of the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Little Theatre on the Square, "The Lion in Winter starring Helen Wagner and Donald May" (1972). 1972 Programs. 12. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/little_theatre_1972_programs/12 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1972 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1972 Programs by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Central Illinois' Only Star Music and Drama Theatre" Sixteenth Season 8 April through October .a Sullivan, Illinois Guy S. Little, Jr. Presents HELEN WAGNER and DONALD MAY "he Lion In Winter" September 19 - October 1, 1972 6uy S. Little, Jr., Presents HELEN DONALD WAGNER MAY "THE LION IN WINTER" By James Goldman with FLOYD KING ALLAN CARLSEN THOMAS LONG KATHY TAYLOR J. P. DOUGHERTY Directed by STUART BISHOP Production ~esignedby ROBERT D. SMLE Costumes Designed by MATHEW JOHN HOFFMAN Ill Lighting Designed by NOEL C. PAYNE Production Stage Manager Assistant to the Costumer Technical Director ROBERT NEU CHRISTINE MEDVE C. G. CARLSON ENTIRE PRODUCTION UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF GUY O. LITTLE, JR. I I CAST Henry II, King of England .......................... :. ............ DONALD MAY Alais, A French Princess ........................................ KATHY TAYLOR John, The Youngest Son ...................................... J. P. DOUGHERTY Geoffrey, The Middle Son ..........................................FLOYD KING Richard Lionheart, The Oldest Son ........................ THOMAS H. LONG, JR. -

The New Hampshire, Vol. 69, No. 18

,,............ ~m.pshire Volume 69 Number 18 Durham, N.H. Proposed rule change draws students'. fire By Rosalie H. Davis this for years. It has been the Student lTovernment leaders backbone of .(Student> Caucus. yesterday criticized a proposal That is the one thing that you can limiting their power to allocate point to and say 'This is what Student Activity Tax money. Caucus does,' " Beckingham said. The propQ_sal, dated Oct. 27, Bill Corson, chairman of the was submitted to student Caucus, said that the new clause organization presidents _for concerning SAT monies removes review by Jeff Onore, chairman direct jurisdiction from students of the Student Organizations and places it in administrators' Committee, and calls for SAT hands. organizations to gain approval of "But," Corson said, ' "this funding from the Student Ac proposal is just a first draft. tivities Office, and the Student J.Gregg <Sanborn) said that it Organizations Committee, two isn't cast in granite. The meeting non-student groups. on the 15th will gauge reaction to The present system allows SAT the proposal better than we can groups to have fundi~ allocated right now," he said. directly by the Student Caucus. The proposal will be discussed Jay Beckingham, Student at an open hearing that SAT Government vice president for organiz~tion presidents have commuter affairs, said he was been invited to attend on Nov. 15. insulted by the proposal's clause Both Onore and Sanborn, the (11.13(s)) which changes the director of Student Affairs, were method of approving the SAT attending a conference in Hyan funds. According to Beckingham, nis, Mass. -

The Wearing and Shedding of Enchanted Shoes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade do Algarve The Wearing and Shedding of Enchanted Shoes THE WEARING AND SHEDDING OF ENCHANTED SHOES Isabel Cardigos* It is now accepted by most that women have played a large role in the transmission of fairytales. Research carried out by Marina Warner1 and also by Ines Köhler- Zülch2 are landmarks on the subject. However, the argument remains that, despite the strength of the female voice throughout women’s renderings of traditional fairytales, it would somehow appear that the genre is inextricably bound with a patriarchal worldview and is, therefore, becoming more and more obsolete. Try as we may, the fairytale perishes with the dew of consciousness-raising. I know that I am not alone in mourning the passing of fairytales. Research into them is not unlike taking part in a wake. But while doing so, let me share with you – with the help of a handful of Portuguese versions – not the hope of bringing fairytales back to life, nor indeed the denial that they are outrageously patriarchal, but the suggestion that we can perhaps detect in them an old beat which is surprisingly modern and adequate. In order to do so, I have chosen the motif of women’s shoes. We are all aware of the rich cluster of sexual imagery that relates the shoe to the foot. We may call to mind Cinderella’s classic glass shoes, a signal of the easily broken nature of virginity,3 and, in the happy outcome of the story, the couple’s perfect union mirrored in the image of the shoe that perfectly matches the foot.4 It is less obvious, however, that shoes are paradoxical objects in that they constrict feet and yet free them to cover greater distances in space. -

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Tuesday through Friday, April 10 –13, 2018, 8pm Saturday, April 14, 2018, 2pm and 8pm Sunday, April 15, 2018, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Alvin Ailey, Founder Judith Jamison, Artistic Director Emerita Robert Battle , Artistic Director Masazumi Chaya, Associate Artistic Director CompAny memBeRs Hope Boykin Jacquelin Harris Akua Noni Parker Jeroboam Bozeman Collin Heyward Danica Paulos Clifton Brown Michael Jackson, Jr. Belén Pereyra-Alem Sean Aaron Carmon Megan Jakel Jamar Roberts Sarah Daley-Perdomo Yannick Lebrun Samuel Lee Roberts Ghrai DeVore Renaldo Maurice Kanji Segawa Solomon Dumas Ashley Mayeux Glenn Allen Sims Samantha Figgins Michael Francis McBride Linda Celeste Sims Vernard J. Gilmore Rachael McLaren Constance Stamatiou Jacqueline Green Chalvar Monteiro Jermaine Terry Daniel Harder Fana Tesfagiorgis Matthew Rushing, Rehearsal Director and Guest Artist Bennett Rink, Executive Director Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts; the New York State Council on the Arts; the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs; American Express; Bank of America; BET Networks; Bloomberg Philanthropies; BNY Mellon; Delta Air Lines; Diageo, North America; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; FedEx; Ford Foundation; Howard Gilman Foundation; The William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; The Prudential Foundation; The SHS Foundation; The Shubert Foundation; Southern Company; Target; The Wallace Foundation; and Wells Fargo. Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. pRoGRAm A k