The Odisha Liveable Habitat Mission: the Process and Tools Behind the World’S Largest Slum Titling Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HIGHSCHOOLS in GANJAM DISTRICT, ODISHA, INDIA Block Type of High Sl

-1- HIGHSCHOOLS IN GANJAM DISTRICT, ODISHA, INDIA Block Type of High Sl. Block G.P. Concerned Village Name of the School Sl. School 1 1 Aska Aska NAC Aska Govt. Girl's High School, Aska Govt. 2 2 Aska Aska NAC Aska Harihar High School, Aska Govt. 3 3 Aska Aska NAC Aska Tech High School, Aska Govt. 4 4 Aska Munigadi G. P. Munigadi U. G. Govt. High School, Munigadi Govt. U.G. 5 5 Aska Mangalpur G. P. Mangalpur Govt. U. G. High School, Mangalpur Govt. U.G. 6 6 Aska Khaira G. P. Babanpur C. S. High School, Babanpur New Govt. 7 7 Aska Debabhumi G. P. Debabhumi G. P. High School, Debabhumi New Govt. 8 8 Aska Gunthapada G. P. Gunthapada Jagadalpur High School, Gunthapada New Govt. 9 9 Aska Jayapur G. P. Jayapur Jayapur High School, Jayapur New Govt. 10 10 Aska Bangarada G. P. Khukundia K & B High School, Khukundia New Govt. 11 11 Aska Nimina G. P. Nimina K. C. Girl's High School, Nimina New Govt. 12 12 Aska Kendupadar G. P. Kendupadar Pragati Bidyalaya, Kendupadar New Govt. 13 13 Aska Baragam Baragam Govt. U.G. High School, Baragam NUG 14 14 Aska Rishipur G.P. Rishipur Govt. U.G. High School, Rishipur NUG 15 15 Aska Aska NAC Aska N. A. C. High School, Aska ULB 16 16 Aska Badakhalli G. P. Badakhalli S. L. N. High School, Badakhalli Aided 17 17 Aska Balisira G. P. Balisira Sidheswar High School, Balisira Aided 18 18 Aska GangapurG. P. K.Ch. Palli Sudarsan High School, K.Ch. -

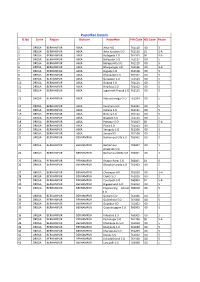

Post Offices of Odisha Circle Covered Under "Core Operation"

Postoffice Details Sl.No Circle Region Division Postoffice PIN Code ND Code Phase 1 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Aska H.O 761110 00 3 2 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Aska Junction S.O 761110 01 5-A 3 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Badagada S.O 761109 00 5-A 4 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Ballipadar S.O 761117 00 5 5 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Bellagunhta S.O 761119 00 5 6 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Bhanjanagar HO 761126 00 3-A 7 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Buguda S.O 761118 00 5 8 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Dharakote S.O 761107 00 5 9 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Gangapur S.O 761123 00 5 10 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Gobara S.O 761124 00 5 11 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Hinjilicut S.O 761102 00 5 12 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Jagannath Prasad S.O 761121 00 5 13 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Kabisuryanagar S.O 761104 00 5 14 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Kanchuru S.O 761101 00 5 15 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Kullada S.O 761131 00 5 16 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Nimina S.O 761122 00 5 17 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Nuagam S.O 761111 00 5 18 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Pattapur S.O 761013 00 5-A 19 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Pitala S.O 761103 00 5 20 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Seragada S.O 761106 00 5 21 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Sorada SO 761108 00 2 22 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Berhampur City S.O 760002 00 5 23 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Berhampur 760007 00 5 University S.O 24 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Berhampur(GM) H.O 760001 00 3 25 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Bhapur Bazar S.O 760001 03 6 26 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Bhatakumarada S.O 761003 00 5 27 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Chatrapur HO 761020 00 3-A 28 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Chikiti S.O 761010 00 5 -

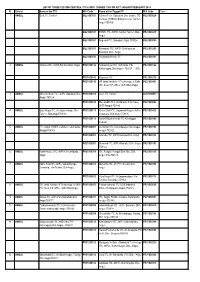

Ganjam District

CHATRAPUR SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 CHATRAPUR 72 2 GANJAM 10 3 RAMBHA 106 4 CHAMAKHANDI 27 5 KHALLIKOTE 120 6 MARINE 02 TOTAL 337 PURUSOTAMPUR SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 PURUSOTAMPUR 56 2 KODALA 75 3 POLOSARA 39 4 KABISURYANAGAR 103 TOTAL 273 ASKA SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 ASKA 606 2 HINJILI 110 3 SHERAGAD A 39 4 PATTAPUR 75 5 DHARAKOTE 109 6 BADAGADA 107 7 SORODA 84 TOTAL 1130 BHANJANAGAR SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 BHANJANAGAR 245 2 BUGUDA 64 3 GANGAPUR 57 4 J.N.PRASAD 37 5 TARASINGH 66 TOTAL 469 NAME OF SUB-DIVISION TOTAL CHATRAPUR SUB-DIVISION 337 PURUSOTAMPUR SUB-DIVISION 273 ASKA SUB-DIVISION 1130 BHANJANAGAR SUB-DIVISION 469 TOTAL 2209 GANJAM PS Sl No. NBW REF NAME THE FATHERS NAME ADDRESS THE CASE REF WARRANTEE WARRANTEE 1. ADDL SESSION Ramuda Krishna Rao S/O- Roga Rao vill- Malada PS/Dist Ganjam ST-75/13 U/S- 147/148/149/307 JUDGE CTR Ganjam . /323/324/337/294/506/34 IPC . 2. 2nd Addl Dist and Bhalu @ Susanta S/O- Bhakari Gouda vill Maheswar Colony SC- 42/07(A) Session Judge , Gouda PS/Dist Ganjam SC—119/05 Chatrapur 3. ASST SESSION Shyam Sundar Behera S/O- Balaram Behera vill- Kalyamar PS/Dist SC-6/96(3) U/S-147/148/294/307/ JUDGE CHATRAPUR @Babula Ganjam . 506/and 7 crl Amendment Act 4. S.D.J. -

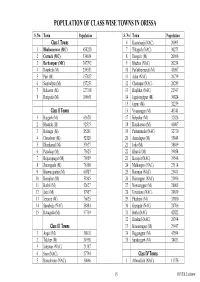

Population of Class Wise Towns in Orissa

POPULATION OF CLASS WISE TOWNS IN ORISSA S. No. Town Population S. No. Town Population Class I Towns 6 Kantabanji (NAC) 20095 1 Bhubaneswar (MC) 658220 7 Titlagarh (NAC) 30273 2 Cuttack (MC) 534654 8 Deogarh (M) 20096 3 Berhampur (MC) 307792 9 Bhuban (NAC) 20234 4 Rourkela (M) 259553 10 Parlakhemundi (M) 43097 5 Puri (M) 157837 11 Aska (NAC) 20739 6 Sambalpur (M) 157253 12 Chatrapur (NAC) 20289 7 Balasore (M) 127358 13 Hinjlikat (NAC) 21347 8 Baripada (M) 100651 14 Jagatsinghpur (M) 30824 15 Jajpur (M) 32239 Class II Towns 16 Vyasanagar (M) 40741 1 Bargarh (M) 63678 17 Belpahar (M) 32826 2 Bhadrak (M) 92515 18 Kendrapara (M) 41407 3 Bolangir (M) 85261 19 Pattamundai (NAC) 32730 4 Choudwar (M) 52528 20 Anandapur (M) 35048 5 Dhenkanal (M) 57677 21 Joda (M) 38689 6 Paradeep (M) 73625 22 Khurda (M) 39054 7 Brajarajnagar (M) 76959 23 Koraput (NAC) 39548 8 Jharsuguda (M) 76100 24 Malkangiri (NAC) 23114 9 Bhawanipatna (M) 60787 25 Karanjia (NAC) 21441 10 Keonjhar (M) 51845 26 Rairangpur (NAC) 21896 11 Barbil (M) 52627 27 Nowrangpur (M) 28005 12 Jatni (M) 57957 28 Umarkote (NAC) 24859 13 Jeypore (M) 76625 29 Phulbani (M) 33890 14 Sunabeda (NAC) 58884 30 Gunupur (NAC) 24706 15 Rayagada (M) 57759 31 Burla (NAC) 42822 32 Hirakud (NAC) 26394 Class III Towns 33 Biramitrapur (M) 29447 1 Angul (M) 38018 34 Rajgangpur (M) 43594 2 Talcher (M) 34998 35 Sundargarh (M) 38421 3 Jaleswar (NAC) 21387 4 Soro (NAC) 27794 Class IV Towns 5 Basudevpur (NAC) 30006 1 Athmallick (NAC) 11376 15 RCUES, Lucknow S. -

(Ttcs) with TAGGED ITIS for AITT JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 Sl

LIST OF TRADE TESTING CENTRES (TTCs) WITH TAGGED ITIS FOR AITT JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 Sl. District Name of the TTC MIS Code Name of the Tagged ITI MIS Code Trade 1 ANGUL Govt. ITI, Talcher GU21000531 Talcher Tech. Education Dev. Centre, ITC PU21000024 Tentulei, (TTEDC) Bidyut Colony, Talcher, Angul-759106. GU21000531 ESSEL ITC, At/PO- Kaniha Talcher, Dist.- PR21000219 Angul, GU21000531 Regional ITC, Banarpal, Angul-759128 PU21000005 GU21000531 Biswanath ITC, At/PO - Budhapanka PR21000209 Banarpal, Dist.- Angul, GU21000531 Sivananda Private ITI PR21000501 2 ANGUL Adarsha ITC, At/PO-Rantalei,Dist- Angul, PR21000142 Satyanarayan ITC, At-Boinda, PO- PR21000122 Kishoreganj, Dist-Angul – 759127 (105) PR21000142 Gayatree ITC PR21000218 PR21000142 OP Jindal Institute of Technology & Skills PU21000453 ITC, Near S.P. Office, At/Po/Dist-Angul, 3 ANGUL Akhandalmani ITC , At/Po. Banarpal, Dist- PR21000410 Govt. ITI, Talcher GU21000531 Angul- 759128. PR21000410 Maa Budhi ITC,l. At-Maratira,P.O-Tubey, PU21000086 DIST-Anugul-759145. 4 ANGUL Guru Krupa ITC, At-Jagannathpur, Via- PR21000113 Shree Dhriti ITC, Jagannath Nagar, At/Po- PR21000323 Talcher, Dist-Angul-759101. Gotamara, Dist-Angul-759135 PR21000113 Swami Nigamananda ITC Narsingpur PR21000400 Cuttack 5 ANGUL ITC, Angul, RCMS, Campus, Hakimpada, PU21000001 Aluminium ITC At-kandasara, Nalconagar, PR21000104 Anugul-759143. Anugul-759122. PU21000001 Adarsha ITC, At/PO-Rantalei,Dist- Angul, PR21000142 PU21000001 Diamond ITC, At/PO-Rantalei, Dist- Angul- PR21000192 759122, 6 ANGUL Kaminimayee ITC, At/Po-Chhendipada, PR21000368 ITC, Rengali, Rengali Dam Site, Dist. PR21000335 Angul. Angul, PIN-759105. 7 ANGUL Matru Sakti ITC, At/Po-Samal Barage, PR21000422 Maharshi ITC, At / PO - Kosala, Dist. - PR21000228 Township, Via-Talcher, Dist-Angul, Angul PR21000422 Guru Krupa ITC, At-Jagannathpur, Via- PR21000113 Talcher, Dist-Angul-759101. -

Orissa High Court Filing Report As on :18/08/2021

ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :18/08/2021 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 1 BLAPL/0006839/2021 SAMUEL HANTAL TUKUNA KUMAR MISHRA JEYPORE TOWN /158 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 2 BLAPL/0006840/2021 DURGA PRASAD PANDA BISWARANJAN DALAI JAGATSINGPUR /345 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 3 BLAPL/0006841/2021 PRADEEP PUJHARI@ PRADEEP KUMAR PUJHARITRILOCHAN NANDA NAWAPARA /165 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 4 BLAPL/0006842/2021 KALIA NAIK GOPAL KRISHNA NAYAK BUGUDA /232 /2014 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 5 BLAPL/0006843/2021 PRASANTA CHOUDHURY @ PRASANTA SAHOOSARADA PRASAD DASH KHANDAPARA /100 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 6 BLAPL/0006844/2021 SAGAR BEHERA BHABANI SANKAR DAS RAMBHA (CHATRAPUR) /303 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 7 BLAPL/0006845/2021 SAGAR BEHERA BHABANI SANKAR DAS RAMBHA (CHATRAPUR) /235 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 8 BLAPL/0006846/2021 HARMEET SINGH ARORA SUMIT KUMAR MOHANTY CANTONMENT ROAD /87 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 9 BLAPL/0006847/2021 SANTOSH BEHERA PRASANNA KUMAR MISHRA GUNUPUR /46 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 10 BLAPL/0006848/2021 UMESH GUNTHA ARIJEET MISHRA NANDAPUR /28 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 11 BLAPL/0006849/2021 ABHIJEET MAHURIA @ JEET MAHURIA ARIJEET MISHRA BORIGUMMA /144 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // Page 1/65 ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :18/08/2021 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 12 BLAPL/0006850/2021 ASHISH IMANUL TAKRI TUKUNA -

Directorate of Indian Medicines & Homoeopathy, Orissa, Bhubaneswar Listof the Homoeopathic Dispensaries GANJAM

Annexure-I Directorate of Indian Medicines & Homoeopathy, Orissa, Bhubaneswar Listof the Homoeopathic Dispensaries GANJAM Sl. Name of the Dispensary Name of G. P. Name of the Block Tribal/Non-Tribal No. 1 Kaniari Kaniari Kabisuryanagar Remote rural area 2 B. Nuapali Baunsia Kabisuryanagar Remote rural area 3 Sodak Sodak Polsara Remote rural area 4 Bagadi Belgaon Polsara Remote rural area 5 Budheisuni Belgaon Polsara Remote rural area 6 Kalamba Kalamba Polsara Remote rural area 7 Mathura Mathura Polsara Remote rural area 8 Khojapali Vikapada Khalikote Remote rural area 9 Langaleswar Langaleswar Khalikote Remote rural area 10 Rajapur Bluttagarsingi Purusottampur Remote rural area 11 Chingudighai Sama Purusottampur Remote rural area 12 Badagudiali Mundamekhala Kodel Remote rural area 13 Beruanbadi Baruanbadi Kodel Remote rural area 14 Malud Malud Ganjam Remote rural area 15 Podangi Podangi Hinjilicut Remote rural area 16 Chemakhandi Chemakhandi Chhatrapupr Rural area 17 Kullad Kullad Bhanjanagar Rural area 18 Badakodanda Badakodanda Bhanjanagar Rural area 19 Birikote Balibeti Bhanjanagar Rural area 20 Domuhani Hariguda Bhanjanagar Rural area 21 Jillundi Jillundi Bhanjanagar Rural area 22 Dadralunda Dadralunda Bhanjanagar Rural area 23 Munigadi Munigadi Aska Rural area 24 Nimapadar Khamarpali Jagannathprasad Rural area 25 Solsola Dhabalpur Sargarh Rural area 26 B.karadabadi B.karadabadi Buguda Rural area 27 Lambhai Lambhai Belguntha Rural area 28 Benipali Benipali Belguntha Rural area 29 Kulangi Kulangi Belguntha Rural area 30 Jharpari Jharpari -

Report on Business Register, Odisha, Khadi and Village Industries Board

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA Report on Business Register, Odisha (Khadi & Village Industries Board ) Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Odisha Bhubaneswar SURESH CHANDRA MAHAPATRA,IAS Tel : 0674-2536882 (O) Development Commissioner-Cum- : 0674-2322617 Additional Chief Secretary & Secy. to Govt. Fax : 0674-2536792 P & C Department Email : [email protected] MESSAGE I am glad to know that Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Odisha has brought out the final Report of "District wise Enterprises Registered under Khadi & Village Industries Board" for publication of Business Register, 2013-14 in the State. It is an important source of information for the statistical analysis of the business population and its demography. The gigantic task of Survey on Business Register undertaken by the officers and staff of DE&S is praiseworthy. I hope this publication would be useful for policy making in the Government. (Suresh Chandra Mahapatra) ସଙ୍କର୍ଷଣସ ାହୁ, ଭା.ପ.ସେ ଅର୍ଥନୀତି ଓ ପରିସଂ孍ୟାନ ଭବନ ନିସଦେଶକ Arthaniti ‘O’ Parisankhyan Bhawan ଅର୍େନୀତି ଓ ପରିେଂଖ୍ୟାନ HOD Campus, Unit-V Sankarsana Sahoo, ISS Bhubaneswar -751001, Odisha Director Phone : 0674 -2391295 Economics & Statistics e-mail : [email protected] Foreword Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India have introduced for preparation of National Business Register. Preparation of Business Register at State Level is a part of it. It aims to verify the physical existence of the establishments registered under seven Registering Authorities in the State. Directorate of Economics & Statistics (DE&S),Odisha conducted field survey on Business Register,2013 throughout the State on complete enumeration basis for collection of data on establishments and enterprises registered under seven Registering Authorities as on 2011-12 and functioning in the areas. -

LIST of Districts, Blocks and Gps User1/Compcell/Mpr/Databank/Apr-Gplist Sh

LIST OF DISTRICTs, BLOCKs AND GPs user1/compcell/mpr/databank/apr-Gplist sh. Agril Range Revenue DAO/ ADAO CIRCLE Block No. of No. of farm District GPs families as per Census '91 1 BALASORE 1 BALASORE DAO BALASORE 1 Balasore 27 21299 2 Basta 22 21255 3 Remuna 28 14349 ADAO JALESWAR 1 Jaleswar 27 22679 2 Bhograi 32 36493 3 Baliapal 27 24700 ADAO NILAGIRI * 1 Nilagiri 25 10948 2 Oupada 11 8510 ADAO SORO 1 Soro 22 14851 2 Bahanaga 21 12627 ADAO SIMULIA 1 Simulia 17 14971 2 Khaira 30 22591 5 12 289 225273 2 BHADRAK DAO BHADRAK 1 Bhadrak 31 22042 2 Bhandaripokhari 19 16900 3 Dhamnagar 30 19936 4 Tihidi 26 21575 5 Chandbali 33 30799 6 Basudevpur 32 28187 ADAO AGARPARA 1 Bonth 22 17378 2 7 193 156817 2 BOLANGIR 3 BOLANGIR DAO BOLANGIR 1 Bolangir 23 12780 2 Deogaon 23 13711 3 Gudvella (Tentulikhunti) 12 9213 4 Puintala 24 16409 5 Loisinga 18 13281 6 Agalpur 18 14811 DAO TITLAGARH 1 Titlagarh 22 17289 2 Saintala 20 16029 3 Bangamunda 22 17004 4 Muribahal 18 17156 5 Tureikela 19 11825 ADAO PATNAGARH 1 Patnagarh 26 16855 2 Belpara 22 14682 3 Khaprakhol 18 15343 3 14 285 206388 4 SONEPUR DAO SONEPUR 1 Sonepur 13 10422 2 Tarva 18 11032 ADAO BIRMAHARAJPUR 1 Biramaharajpur 13 13968 2 Ullunda 16 11756 ADAO DUNGRIPALI 1 Dunguripalli 21 19477 2 Binka 15 15104 3 6 96 81759 3 CUTTACK 5 CUTTACK DAO CUTTACK 1 Cuttack 21 6976 2 Barang 16 4824 3 Niali 23 17916 4 Kantapada 14 8153 ADAO SALIPUR 1 Salipur 32 11669 2 Nischintakoili 40 15184 3 Mahanga 34 19207 4 Tangi-Choudwar 20 11840 DAO ATHGARH 1 Athgarh 29 14011 2 Tigiria 10 6482 3 Badamba 36 15323 4 Narsinghpur -

Orissa High Court Filing Report As on :30/06/2021

ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :30/06/2021 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 1 BLAPL/0004961/2021 MANGAL SINGH MUNDARY BIREN SANKAR TRIPATHY K.BALANG /51 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 2 BLAPL/0004962/2021 DIPTIMAYA SAMANTARAY SATYA RANJAN MULIA DHENKANAL SADAR /403 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 3 BLAPL/0004963/2021 MITHILESH GUPTA SATYA RANJAN MULIA BANARAPAL /186 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 4 BLAPL/0004964/2021 AJIT KUMAR SINGH PRASANNA KUMAR MISHRA S.P.(CID-CRL),CUTTACK /33 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 5 BLAPL/0004965/2021 NABIR SK. @ NOBIR SK. SHAKTI PRASAD DAS JHUMPURA /26 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 6 BLAPL/0004966/2021 TUKUNA SAHU ASHOK KUMAR SARANGI BANTALA /126 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 7 BLAPL/0004967/2021 ABODH KUMAR SETHY SUSHANTA HARICHANDAN / /0 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 8 BLAPL/0004968/2021 SAMI ULLHA SIDDIQUI JAGANNATH KAMILA KORAPUT TOWN /222 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 9 BLAPL/0004969/2021 PRAKASH CHANDRA BEHERA BHABANI SANKAR DAS NUAGAM (DIGAPAHANDI) /125 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 10 BLAPL/0004970/2021 BIJAY MOHANTY DASRATHI DASH SPL.TASK FORCE /15 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 11 BLAPL/0004971/2021 HEMANTA KUMAR BEHERA CHANDAN SAMANTARAY K.NUAGAON /280 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // Page 1/37 ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :30/06/2021 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 12 BLAPL/0004972/2021 GHANASHYAM RANA SATYABRATA PANDA KANTAMAL -

District Statistical Hand Book, Ganjam, 2018

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK GANJAM 2018 DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS, ODISHA ARTHANITI ‘O’ PARISANKHYAN BHAWAN HEADS OF DEPARTMENT CAMPUS, BHUBANESWAR PIN-751001 Email : [email protected]/[email protected] Website : desorissa.nic.in [Price : Rs.25.00] ସଙ୍କର୍ଷଣ ସାହୁ, ଭା.ପ.ସେ ଅର୍ଥନୀତି ଓ ପରିସଂ孍ୟାନ ଭବନ ନିସଦେଶକ Arthaniti ‘O’ Parisankhyan Bhawan ଅର୍େନୀତି ଓ ପରିେଂଖ୍ୟାନ HOD Campus, Unit-V Sankarsana Sahoo, ISS Bhubaneswar -751005, Odisha Director Phone : 0674 -2391295 Economics & Statistics e-mail : [email protected] Foreword I am very glad to know that the Publication Division of Directorate of Economics & Statistics (DES) has brought out District Statistical Hand Book-2018. This book contains key statistical data on various socio-economic aspects of the District and will help as a reference book for the Policy Planners, Administrators, Researchers and Academicians. The present issue has been enriched with inclusions like various health programmes, activities of the SHGs, programmes under ICDS and employment generated under MGNREGS in different blocks of the District. I would like to express my thanks to Dr. Bijaya Bhusan Nanda, Joint Director, DE&S, Bhubaneswar for his valuable inputs and express my thanks to the officers and staff of Publication Division of DES for their efforts in bringing out this publication. I also express my thanks to the Deputy Director (P&S) and his staff of DPMU, Ganjam for their tireless efforts in compilation of this valuable Hand Book for the District. Bhubaneswar (S. Sahoo) May, 2020 Dr. Bijaya Bhusan Nanda, O.S. & E.S.(I) Joint Director Directorate of Economics & Statistics Odisha, Bhubaneswar Preface The District Statistical Hand Book, Ganjam’ 2018 is a step forward for evidence based planning with compilation of sub-district level information. -

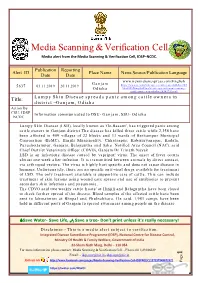

Media Scanning & Verification Cell

Media Scanning & Verification Cell Media alert from the Media Scanning & Verification Cell, IDSP-NCDC. Publication Reporting Alert ID Place Name News Source/Publication Language Date Date www.newindianexpress.com/English Ganjam 5637 03.11.2019 20.11.2019 https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/odisha/201 Odisha 9/nov/03/lumpy-skin-disease-spreads-panic-among- cattle-owners-in-odisha-2056375.html Lumpy Skin Disease spreads panic among cattle owners in Title: district –Ganjam, Odisha Action By CSU, IDSP Information communicated to DSU- Ganjam, SSU- Odisha –NCDC Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD), locally known as ‘Go-Basant’, has triggered panic among cattle owners in Ganjam district.The disease has killed three cattle while 2,356 have been affected in 409 villages of 22 blocks and 33 wards of Berhampur Municipal Corporation (BeMC), Hinjili Municipality, Chhatrapur, Kabisuryanagar, Kodala, Purushottampur, Ganjam, Belaguntha and Aska Notified Area Council (NAC), said Chief District Veterinary Officer (CDVO), Ganjam Dr Trinath Nayak. LSD is an infectious disease caused by ‘capripox’ virus. The onset of fever occurs almost one week after infection. It is transmitted between animals by direct contact, via arthropod vectors. The virus is highly host specific and does not cause disease in humans. Unfortunately, there are no specific anti-viral drugs available for treatment of LSD. The only treatment available is supportive care of cattle. This can include treatment of skin lesions using wound care sprays and use of antibiotics to prevent secondary skin infections and pneumonia. The CDVO said two weekly cattle ‘haats’ at Hinjili and Belaguntha have been closed to check further spread of the disease.