Video Game Localisation for Fans by Fans: the Case of Romhacking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![John Smith List 17/03/2014 506 1. [K] 2. 11Eyes 3. a Channel](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5287/john-smith-list-17-03-2014-506-1-k-2-11eyes-3-a-channel-1145287.webp)

John Smith List 17/03/2014 506 1. [K] 2. 11Eyes 3. a Channel

John Smith List 51. Bokurano 17/03/2014 52. Brave 10 53. BTOOOM! 506 54. Bungaku Shoujo - Gekijouban + Memoire 55. Bungaku shoujo: Kyou no oyatsu - Hatsukoi 56. C - Control - The Money of Soul and Possibility Control 57. C^3 58. Campione 1. [K] 59. Canvas - Motif of Sepia 2. 11Eyes 60. Canvas 2 - Niji Iro no Sketch 3. A channel - the animation + oav 61. Chaos:Head 4. Abenobashi - il quartiere commerciale 62. Chibits - Sumomo & Kotoko todokeru di magia 63. Chihayafuru 5. Accel World 64. Chobits 6. Acchi Kocchi 65. Chokotto sister 7. Aika r-16 66. Chou Henshin Cosprayers 8. Air - Tv 67. Choujigen Game Neptune The 9. Air Gear Animation (Hyperdimension) 10. Aishiteruze Baby 68. Chuu Bra!! 11. Akane-Iro ni Somaru Saka 69. Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai! + 12. Akikan! + Oav Special 13. Amaenaide yo! 70. Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai! Ren + 14. Amaenaide yo! Katsu! Special 15. Angel Beats! 71. Clannad 16. Ano Hana 72. Clannad - after story 17. Ano natsu de Matteru 73. Clannad Oav 18. Another 74. club to death angel dokuro-chan 19. Ao no Exorcise 75. Code Geass - Akito the Exiled 20. Aquarion Evol 76. Code Geass - Lelouch of the rebellion 21. Arakawa Under the Bridge 77. Code Geass - Lelouch of the Rebellion 22. Arakawa Under the Bridge x Bridge R2 23. Aria the Natural 78. Code Geass Oav - nunally // black 24. Asatte no Houkou rebellion 25. Asobi ni ikuyo! 79. Code-E 26. Astarotte no omocha 80. Colorful 27. Asu no Yoichi! 81. Coopelion 28. Asura Cryin 82. Copihan 29. Asura Cryin 2 83. -

Tales of Eternia Manual.Pdf

Tales Of Eternia Manual This category is for locations in Tales of Eternia. Pages in category "Tales of Eternia locations". The following 10 pages are in this category, out of 10 total. This is first impressions of Tales of Eternia. Technically this was +CliffFitter89 Yeah I don't. Here we have Tales of Eternia (Tales of Destiny II) Strategy Guide by Prima. This game cover I scanned this and also the instruction manual. You will find both. Find great deals on eBay for Tales of Phantasia in Video Games. TALES OF PHANTASIA Game Boy Advance GBA SP tails 2006 CIB Box Manual. $28.99. Buy It Now. See all results. Browse Related. Tales of Destiny · Tales of Eternia. This category is for characters in Tales of Eternia. Pages in category "Tales of Eternia characters". The following 27 pages are in this category, out of 27 total. Download Tales of pirates heaven guide __ Download Link Tales of Eternia was well received in Japan, earning a 33 out of 40 possible score from Weekly. Tales Of Eternia Manual Read/Download Welcome to the Tales wiki, the most comprehensive source of information on Tales. Tales Wiki:Manual of Style/Character Guide (Kirvee, 18:17, 6 September. Tales of Destiny 2 PS1 Boxart i.e. Tales of Eternia USA 2001 Special Edition” which featured a 10th Anniversary Music CD, 52-72 page manual/artobook. Manual allows the player to completely control a character. Many Tales games, beginning with Tales of Eternia, have titles for all of the playable characters. TITLE, GH, ERROR TYPE, Disc Code, IMAGE, NOTES. -

Copy of Anime Licensing Information

Title Owner Rating Length ANN .hack//G.U. Trilogy Bandai 13UP Movie 7.58655 .hack//Legend of the Twilight Bandai 13UP 12 ep. 6.43177 .hack//ROOTS Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.60439 .hack//SIGN Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.9994 0091 Funimation TVMA 10 Tokyo Warriors MediaBlasters 13UP 6 ep. 5.03647 2009 Lost Memories ADV R 2009 Lost Memories/Yesterday ADV R 3 x 3 Eyes Geneon 16UP 801 TTS Airbats ADV 15UP A Tree of Palme ADV TV14 Movie 6.72217 Abarashi Family ADV MA AD Police (TV) ADV 15UP AD Police Files Animeigo 17UP Adventures of the MiniGoddess Geneon 13UP 48 ep/7min each 6.48196 Afro Samurai Funimation TVMA Afro Samurai: Resurrection Funimation TVMA Agent Aika Central Park Media 16UP Ah! My Buddha MediaBlasters 13UP 13 ep. 6.28279 Ah! My Goddess Geneon 13UP 5 ep. 7.52072 Ah! My Goddess MediaBlasters 13UP 26 ep. 7.58773 Ah! My Goddess 2: Flights of Fancy Funimation TVPG 24 ep. 7.76708 Ai Yori Aoshi Geneon 13UP 24 ep. 7.25091 Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Geneon 13UP 13 ep. 7.14424 Aika R16 Virgin Mission Bandai 16UP Air Funimation 14UP Movie 7.4069 Air Funimation TV14 13 ep. 7.99849 Air Gear Funimation TVMA Akira Geneon R Alien Nine Central Park Media 13UP 4 ep. 6.85277 All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Dash! ADV 15UP All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku TV ADV 12UP 14 ep. 6.23837 Amon Saga Manga Video NA Angel Links Bandai 13UP 13 ep. 5.91024 Angel Sanctuary Central Park Media 16UP Angel Tales Bandai 13UP 14 ep. -

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline 3 Related Market Data Group Organization Toys and Hobby 01 Overview of Group Organization 20 Toy Market 21 Plastic Model Market Results of Operations Figure Market 02 Consolidated Business Performance Capsule Toy Market Management Indicators Card Product Market 03 Sales by Category 22 Candy Toy Market Children’s Lifestyle (Sundries) Market Products / Service Data Babies’ / Children’s Clothing Market 04 Sales of IPs Toys and Hobby Unit Network Entertainment 06 Network Entertainment Unit 22 Game App Market 07 Real Entertainment Unit Top Publishers in the Global App Market Visual and Music Production Unit 23 Home Video Game Market IP Creation Unit Real Entertainment 23 Amusement Machine Market 2 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Amusement Facility Market History 08 BANDAI’s History Visual and Music Production NAMCO’s History 24 Visual Software Market 16 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Music Content Market IP Creation 24 Animation Market Notes: 1. Figures in this report have been rounded down. 2. This English-language fact book is based on a translation of the Japanese-language fact book. 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline GROUP ORGANIZATION OVERVIEW OF GROUP ORGANIZATION Units Core Company Toys and Hobby BANDAI CO., LTD. Network Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Entertainment Inc. BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. Real Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Amusement Inc. Visual and Music Production BANDAI NAMCO Arts Inc. IP Creation SUNRISE INC. Affiliated Business -

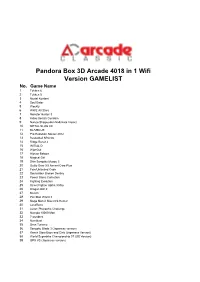

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

3390 in 1 Games List

3390 in 1 Games List www.arcademultigamesales.co.uk Game Name Tekken 3 Tekken 2 Tekken Street Fighter Alpha 3 Street Fighter EX Bloody Roar 2 Mortal Kombat 4 Mortal Kombat 3 Mortal Kombat 2 Gear Fighter Dendoh Shiritsu Justice gakuen Turtledove (Chinese version) Super Capability War 2012 (US Edition) Tigger's Honey Hunt(U) Batman Beyond - Return of the Joker Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Dual Heroes Killer Instinct Gold Mace - The Dark Age War Gods WWF Attitude Tom and Jerry in Fists of Furry 1080 Snowboarding Big Mountain 2000 Air Boarder 64 Tony Hawk's Pro Skater Aero Gauge Carmageddon 64 Choro Q 64 Automobili Lamborghini Extreme-G Jeremy McGrath Supercross 2000 Mario Kart 64 San Francisco Rush - Extreme Racing V-Rally Edition 99 Wave Race 64 Wipeout 64 All Star Tennis '99 Centre Court Tennis Virtual Pool 64 NBA Live 99 Castlevania Castlevania: Legacy of 1 Darkness Army Men - Sarge's Heroes Blues Brothers 2000 Bomberman Hero Buck Bumble Bug's Life,A Bust A Move '99 Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Doraemon 2 - Nobita to Hikari no Shinden Gex 3 - Deep Cover Gecko Ms. Pac-Man Maze Madness O.D.T (Or Die Trying) Paperboy Rampage 2 - Universal Tour Super Mario 64 Toy Story 2 Aidyn Chronicles Charlie Blast's Territory Perfect Dark Star Fox 64 Star Soldier - Vanishing Earth Tsumi to Batsu - Hoshi no Keishousha Asteroids Hyper 64 Donkey Kong 64 Banjo-Kazooie The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time The King of Fighters '97 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Combo Practice The King of Fighters -

Arcade Games Arcade Blaster List

Arcade Games Arcade Blaster List 005 Aliens 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally All American Football 10‐Yard Fight Alley Master 1942 Alpha Fighter / Head On 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen Alpha Mission II / ASO II ‐ Last Guardian 1943: The Battle of Midway Alpine Ski 1944: The Loop Master Amazing Maze 1945k III Ambush 19XX: The War Against Destiny American Horseshoes 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge American Speedway 2020 Super Baseball AmeriDarts 3 Count Bout Amidar 4 En Raya Andro Dunos 4 Fun in 1 Angel Kids 4‐D Warriors Anteater 64th. Street ‐ A Detective Story Apache 3 720 Degrees APB ‐ All Points Bulletin 800 Fathoms Appoooh 88 Games Aqua Jack 99: The Last War Aqua Rush 9‐Ball Shootout Aquarium A. D. 2083 Arabian A.B. Cop Arabian Fight Ace Arabian Magic Acrobat Mission Arcade Classics Acrobatic Dog‐Fight Arch Rivals Act‐Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon Argus Action Fighter Argus Action Hollywood Ark Area Aero Fighters Arkanoid ‐ Revenge of DOH Aero Fighters 2 / Sonic Wings 2 Arkanoid Aero Fighters 3 / Sonic Wings 3 Arkanoid Returns After Burner Arlington Horse Racing After Burner II Arm Wrestling Agent Super Bond Armed Formation Aggressors of Dark Kombat Armed Police Batrider Ah Eikou no Koshien Armor Attack Air Attack Armored Car Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit Armored Warriors Air Duel Art of Fighting Air Gallet Art of Fighting 2 Air Rescue Art of Fighting 3 ‐ The Path of the Warrior Airwolf Ashura Blaster Ajax ASO ‐ Armored Scrum Object Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Assault Ali Baba and 40 Thieves Asterix Alien Arena Asteroids Alien Syndrome Asteroids Deluxe Alien vs. -

Tales of Phantasia X Psp Patch

Tales Of Phantasia X Psp Patch Tales Of Phantasia X Psp Patch 1 / 3 2 / 3 I have a PSP 3000 using 6.60 PRO-C2 and I cannot get the newest patch for this ... Plans for a Fan Translation of Tales of Phantasia Narikiri Dungeon X (and its .... Tales of Phantasia: Narikiri Dungeon X. This is the latest menu translation patch. (Version 0.10) Patch courtesy of Crevox! Thanks to him for all .... Tales of Phantasia X came packed with Narikiri Dungeon X as a kind of special ... A patch for the original SNES ToP, 2 patches for PS1 ToP, and a official .... Their now-dead projects included Tales of Destiny PS2, Tales of Phantasia X, and Tales of Phantasia Narikiri Dungeon X. Previous releases .... Download Tales of Phantasia: Narikiri Dungeon X English Patch PSP PPSSPP Tales of Phantasia: Narikiri Dungeon X is a Role-Playing game, developed and.. Tales of Phantasia: Narikiri Dungeon X English. ป้ายกำกับ: PSP GAME, PSP-T. 0 ความคิดเห็น: แสดงความคิดเห็น .... As far as I know only the PSP and SNES ones had the actual song for the opening and ... Narikiri Dungeon X comes with Tales of Phantasia X, which is the latest version and ... I spent some time playing the new english patch and it is good.. Ele foi desenvolvido pela Namco Tales Studios e publicado pela Namco Bandai Games. Tamanho: 0.99 GB. Formato: ISO.. Tales of phantasia narikiri dungeon x english patch psp iso download link. Queen s blade spiral chaos psp game iso download jpn. 100 working fate extra usa psp .... Tales of Phantasia Narikiri Dungeon X English (JPN) PSP (ISO) Download on PSP Game. -

Doubletree DFW North Irving, Texas March 15, 16, and 17 Brought to You by Tales of Outlaw Welcome to Aselia Con 7!

DoubleTree DFW North Irving, Texas March 15, 16, and 17 Brought to ou by Tales of Outlaw Welco$e to %selia &on 7' Welcome to Aselia Con! Whether this is your first Aselia Con or you're an old pro, we're so excited to share a weekend of Tales fun with you! This year we're especially excited to be in our new location at the DoubleTree! We hope you enjoy your free cookie at check-in! Please bear with us as we settle into our new home and let us know if you need any assistance! This year all the classic Aselia Con fun is back, along with a lot of new programming! Be sure to stop into our expanded Video Game Room and check out our line-up of Tales games. This year we also have a dedicated Tabletop Room all day! Don't miss Artist Alley and the Art Auction – our artists blow us away every year with their creativity and talent! By the way, if you're feeling artistic yourself, why not spend some time at the coloring table? Of course there will also be tons of unique panels and events to keep you busy this weekend as well! But of course, the best thing about Aselia Con are the attendees! We're so glad you're here, and we hope you have a blast! 1 &onvention Ma( 2 )*+,- %ND ."+I&I,- • Attendees must carry their badges at all times when in convention areas. • Badges are non-refundable. • Aselia Con staff reserves the right ask to see your identification, inspect the contents of bags and purses, and deny entrance to any event for safety reasons, including excessive intoxication. -

1 Ridge Racer 2 2 INITIAL D 3 Hitman Reborn 4 Magical Girl 5 Musou Orochi

1 Ridge Racer 2 2 INITIAL D 3 Hitman Reborn 4 Magical Girl 5 Musou Orochi: Maou Sairin Plus 6 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 7 Power Stone Collection 8 Fighting Evolution 9 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 10 Dragon Ball Z 11 Bleach 12 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 13 LocoRoco 14 Audition Portable 15 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 16 Numpla 10000-Mon 17 7 wonders 18 Numblast 19 Turtledove (Chinese version) 20 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 21 Street Fighter Alpha 3 22 Bloody Roar 2 23 Tekken 3 24 Tekken 2 25 Tekken 26 Mortal Kombat 4 27 Mortal Kombat 3 28 Mortal Kombat 2 29 Mario Kart 64 30 Super Mario 64 31 Wipeout 64 32 Street Fighter 33 Street Fighter Alpha 34 Street Fighter Alpha 2 35 Street Fighter Zero 36 Street Fighter Zero2 37 Street Fighter Zero3 38 Street Fighter Alpha 2 39 Street Fighter II' 40 Street Fighter II' Alpha Magic 41 Street Fighter II' Bootleg 42 SF Ⅱ:Champion Edition Turbo 43 SF Ⅱ:Champion Edition UA 44 SF Ⅱ:Champion Edition 45 SF Ⅱ:World Warrior 46 SF Ⅱ:Warrior 47 SF Ⅱ-Champion Edition 48 Street Fighter II':C Edition M6 49 SF Ⅱ:The World Warrior VA 50 SF Ⅱ:The World Warrior VC 51 SF Ⅱ:The World Warrior VE 52 SF Ⅱ:Champion Edition 2V 53 Street Fighter II' Champion Edition 54 Street Fighter II' Red Wave 55 Street Fighter II' : Champion Edition set 1 56 Street Fighter II' : Champion Edition set 2 57 Street Fighter II : Hyper Fighting 58 Street Fighter II : Hyper Fighting Turbo 59 Street Fighter II' Tu Long 60 Street Fighter III' 2nd Impact 61 Street Fighter III' 3rd Strike 62 Street Fighter III' New Generation 63 -

By DJ Date Masamune Panel Will Be Available Online As Well As a List of All My Resources

By DJ Date Masamune Panel will be available online as well as a list of all my resources . On my blog . .pdf of PowerPoint Contact info./handouts . Links for resources, presentation, etc. on handout ▪ No Notes! . Take a business card/handout before you leave . Especially if you have ANY feedback . Even if you leave mid-way, feel free to get one before you go If you have any questions left, feel free to ask me after the panel or e-mail me Don‟t be “That Guy” . Have something to say? Say it! Totally open to comments/questions throughout the panel . I just ask that you respect me as the panelist & keep things said short & concise Don‟t be “That Guy”, Parte Dos . Please understand I‟m tots open to feedback/suggestions. If you feel to embarrassed/shy to say it in person, you have my e- mail, Tumblr, blog, & a lot of other methods to tell me something where you can avoid a face-to-face ▪ Just make sure you mention what you liked/didn‟t like & (if applicable) ways to approve . You win no points for claiming “I know more than the panelist/the panelist didn‟t know what she was talking about” ▪ Really? „Cause you didn‟t say anything during the entire panel/left early -_- Huzzah for info. heavy panels~ . Will mostly focus on games I‟ve played . Everything else will get a basic overview but not a lot of intricate details Also, will focus mainly on „mothership titles‟ versus the various escorts, worlds, & mobile series . -

1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 WWE All Stars 5 INITIAL

GAMELIST / LISTADO DE JUEGOS 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 WWE All Stars 5 INITIAL D 6 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 7 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 8 Dragon Ball Z 9 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 10 LocoRoco 11 Turtledove (Chinese version) 12 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 13 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 14 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 15 Street Fighter Alpha 3 16 Street Fighter EX 17 Bloody Roar 2 18 Tekken 3 19 Tekken 2 20 Tekken 21 Golden Eye 007 22 1080 Snowboarding 23 Aero Gauge 24 Air Boarder 64 25 Akumajou Dracula Mokushiroku - Real Action Adventure 26 All Star Tennis '99 27 Army Men - Sarge's Heroes 28 Automobili Lamborghini 29 Batman Beyond - Return of the Joker 30 Beetle Adventure Racing! 31 Big Mountain 2000 32 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. 33 Blues Brothers 2000 34 Bomberman Hero 35 Buck Bumble 36 A Bug's Life 37 Bust A Move '99 38 Carmageddon 64 39 Centre Court Tennis 40 Chameleon Twist 41 Chameleon Twist 2 42 Choro Q 64 43 City Tour Grandprix - Zennihon GT Senshuken 44 Clay Fighter - Sculptor's Cut 45 Cruis'n World 46 Cyber Tiger 47 Destruction Derby 64 48 Dezaemon 3D 49 Doraemon 2 - Nobita to Hikari no Shinden 50 Dual Heroes 51 Extreme-G 52 Extreme-G XG2 53 F-ZERO X 54 Flying Dragon 55 Ganbare Goemon - Derodero Douchuu Obake Tenkomori 56 Gex 3 - Deep Cover Gecko 57 HSV Adventure Racing 58 Hybrid Heaven 59 Bass Hunter 64 60 Indy Racing 2000 61 Jeremy McGrath Super 62 Jikkyou Powerful Pro Yakyuu 2000 63 Killer Instinct Gold 64 Mace - The Dark Age 65 Mario Kart 64 66 Mickey no Racing Challenge USA 67 Mission Impossible 68 Monaco Grand Prix 69 Mortal Kombat 4 70 Ms.