An Exploration of Age-Gap Relationships in Western Society" (2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

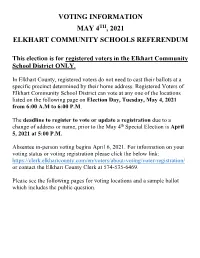

Voting Information May 4 , 2021 Elkhart Community

VOTING INFORMATION MAY 4TH, 2021 ELKHART COMMUNITY SCHOOLS REFERENDUM This election is for registered voters in the Elkhart Community School District ONLY. In Elkhart County, registered voters do not need to cast their ballots at a specific precinct determined by their home address. Registered Voters of Elkhart Community School District can vote at any one of the locations listed on the following page on Election Day, Tuesday, May 4, 2021 from 6:00 A.M to 6:00 P.M. The deadline to register to vote or update a registration due to a change of address or name, prior to the May 4th Special Election is April 5, 2021 at 5:00 P.M. Absentee in-person voting begins April 6, 2021. For information on your voting status or voting registration please click the below link: https://clerk.elkhartcounty.com/en/voters/about-voting/voter-registration/ or contact the Elkhart County Clerk at 574-535-6469. Please see the following pages for voting locations and a sample ballot which includes the public question. Voting Locations 1. Trinity United Methodist Church 9. Osolo Township Fire Station 2715 E. Jackson Street 24936 Buddy Street Elkhart, IN 46516 Elkhart, IN 46514 Interurban Trolley Route-Blue 2. St. James AME Church 10. Granger Community Church 122 Dr. Martin Luther King Dr. Elkhart Campus, 2701 E. Bristol St. Elkhart, IN 46516 Elkhart, IN 46514 Interurban Trolley Route-Green/Red/Orange 3. River of Life Community Church 11. Fraternal Order of Police FOP #52 2626 Prairie Street 1003 Industrial Parkway Elkhart, IN 46517 Elkhart, IN 46516 Interurban Trolley Route-Green/Red/Orange Interurban Trolley Route-Orange 4. -

An Interdisciplinary Study of Economic History, Anthropology, and Queer Theory

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Fall 11-30-2012 Transgressing Sexuality: An Interdisciplinary Study of Economic History, Anthropology, and Queer Theory Jason Gary Damron Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Damron, Jason Gary, "Transgressing Sexuality: An Interdisciplinary Study of Economic History, Anthropology, and Queer Theory" (2012). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 622. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.622 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Transgressing Sexuality: An Interdisciplinary Study of Economic History, Anthropology, and Queer Theory by Jason Gary Damron A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Thesis Committee: Michele R. Gamburd, Chair Mary C. King Leerom Medovoi DeLys Ostlund Portland State University 2012 ©2012 Jason Gary Damron Abstract This interdisciplinary thesis examines the concept of sexuality through lenses provided by economic history, anthropology, and queer theory. A close reading reveals historical parallels from the late 1800s between concepts of a desiring, utility-maximizing economic subject on the one hand, and a desiring, carnally decisive sexological subject on the other. Social constructionists have persuasively argued that social and economic elites deploy the discourse of sexuality as a technique of discipline and social control in class- and gender-based struggles. -

This Project Brings Together Girls' Studies, Feminist Psychology, And

1 Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ______________ Kelly H. Ball Date “So Powerful a Form”: Rethinking Girls’ Sexuality By Kelly H. Ball Doctor of Philosophy Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies _______________________________________ Lynne Huffer, Ph.D. Advisor _______________________________________ Elizabeth A. Wilson, Ph.D. Advisor ________________________________________ Cynthia Willett, Ph.D. Committee Member ________________________________________ Mary E. Odem, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date “So Powerful a Form”: Rethinking Girls’ Sexuality By Kelly H. Ball M.A. The Ohio State University, 2008 B.A. Transylvania University, 2006 Advisor: Lynne Huffer, Ph.D. Advisor: Elizabeth A. Wilson, Ph.D. An abstract of A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies 2014 Abstract “So Powerful a Form”: Rethinking Girls’ Sexuality By: Kelly H. -

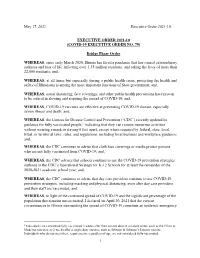

Bridge Phase Executive Order

May 17, 2021 Executive Order 2021-10 EXECUTIVE ORDER 2021-10 (COVID-19 EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 79) Bridge Phase Order WHEREAS, since early March 2020, Illinois has faced a pandemic that has caused extraordinary sickness and loss of life, infecting over 1.35 million residents, and taking the lives of more than 22,000 residents; and, WHEREAS, at all times but especially during a public health crisis, protecting the health and safety of Illinoisans is among the most important functions of State government; and, WHEREAS, social distancing, face coverings, and other public health precautions have proven to be critical in slowing and stopping the spread of COVID-19; and, WHEREAS, COVID-19 vaccines are effective at preventing COVID-19 disease, especially severe illness and death; and, WHEREAS, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (“CDC”) recently updated its guidance for fully vaccinated people,1 indicating that they can resume numerous activities without wearing a mask or staying 6 feet apart, except where required by federal, state, local, tribal, or territorial laws, rules, and regulations, including local business and workplace guidance; and, WHEREAS, the CDC continues to advise that cloth face coverings or masks protect persons who are not fully vaccinated from COVID-19; and, WHEREAS, the CDC advises that schools continue to use the COVID-19 prevention strategies outlined in the CDC’s Operational Strategy for K-12 Schools for at least the remainder of the 2020-2021 academic school year; and, WHEREAS, the CDC continues to advise that -

Competing for Love: Applying Sexual Economics Theory to Mating Contests ⇑ Roy F

Journal of Economic Psychology 63 (2017) 230–241 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Economic Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/joep Competing for love: Applying sexual economics theory to mating contests ⇑ Roy F. Baumeister a,b, , Tania Reynolds a, Bo Winegard a, Kathleen D. Vohs c a Florida State University, United States b University of Queensland, Australia c University of Minnesota, United States article info abstract Article history: Sexual economics theory analyzes the onset of heterosexual sex as a marketplace deal in Received 21 May 2016 which the woman is the seller and the man is the buyer, with the price paid in nonsexual Received in revised form 16 July 2017 resources. We extend that theory to analyze same-gender contests in that marketplace, Accepted 27 July 2017 and to elaborate the idea that what the woman sells is not just sex but exclusive access Available online 29 July 2017 to her sexual charms. Women compete on sex appeal and on the promise of exclusiveness (faithfulness), with the goal of getting a man who will provide material resources. Men Keywords: compete to amass material resources, with the goal of getting a good sex partner. Sex Female competition includes showing off her sexual charms, offering sex at a lower price Sexuality Mating than rivals, seeking to improve her physical assets (e.g., by dieting), and use of informa- Gender tional warfare to sully rivals’ reputations while defending her own reputation against mali- Competition cious gossip. We review evidence of these patterns, including evidence that female body Sexual economics dissatisfaction and pathological eating patterns increase when women perceive an unfa- Contest vorable sex ratio (i.e., shortage of eligible men). -

![PSY 306 #43115 Syllabus 1.10.16[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2313/psy-306-43115-syllabus-1-10-16-1-552313.webp)

PSY 306 #43115 Syllabus 1.10.16[1]

Intro to Human Sexuality (PSY 306): Overview Cindy M. Meston, Ph.D. & David M. Buss, Ph.D. Introduction. Welcome to Intro to Human Sexuality. In this course, you will learn about all the stages of the human sexual response including: sexual attraction, sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm. You will learn what enhances and what inhibits each of these stages from psychological (e.g., relationships, mood, past experiences), evolutionary (e.g., how mating strategies evolved), and physiological (e.g., hormonal, neurological) perspectives. You will become familiar with different sexual problems that are clinically diagnosable, and how they are treated either with psychotherapy, medical intervention, or both. You will learn about sexual motivation and the many factors that influence sexual decision making such as jealousy, mate guarding, competition, duty, and economics. Our goal is to give you a broad overview of how humans function sexually. Two key perspectives in this course will be an evolutionary perspective and a clinical perspective, although multiple theoretical perspectives on human sexuality will be covered. Human sexuality has been a core research interest of both professors for many years. We are excited about co-teaching this course, and hope you will be excited about taking it. Sex in the news. Sexual topics frequently make the news. News often deal with topics such as infidelity or other sexual improprieties by high status individuals such as politicians; internet dating sites that become popular or are hacked; prostitution, pornography, polyamory, and other new scientific findings about human sexuality. A unique feature of this course is a ‘sex in the news’ segment that will occur regularly throughout the course where relevant and as sex appears in the news. -

PRAC Recommendations on Signals Adopted at the 3-6 May 2021 PRAC Meeting

31 May 20211 EMA/PRAC/250777/2021 Corr 2 Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) PRAC recommendations on signals Adopted at the 3-6 May 2021 PRAC meeting This document provides an overview of the recommendations adopted by the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) on the signals discussed during the meeting of 3-6 May 2021 (including the signal European Pharmacovigilance Issues Tracking Tool [EPITT]3 reference numbers). PRAC recommendations to provide supplementary information are directly actionable by the concerned marketing authorisation holders (MAHs). PRAC recommendations for regulatory action (e.g. amendment of the product information) are submitted to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) for endorsement when the signal concerns Centrally Authorised Products (CAPs), and to the Co-ordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures – Human (CMDh) for information in the case of Nationally Authorised Products (NAPs). Thereafter, MAHs are expected to take action according to the PRAC recommendations. When appropriate, the PRAC may also recommend the conduct of additional analyses by the Agency or Member States. MAHs are reminded that in line with Article 16(3) of Regulation No (EU) 726/2004 and Article 23(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC, they shall ensure that their product information is kept up to date with the current scientific knowledge including the conclusions of the assessment and recommendations published on the European Medicines Agency (EMA) website (currently acting as the EU medicines webportal). For CAPs, at the time of publication, PRAC recommendations for update of product information have been agreed by the CHMP at their plenary meeting (17-20 May 2021) and corresponding variations will be assessed by the CHMP. -

Calendar of Events May – August 2021

CALENDAR OF EVENTS MAY – AUGUST 2021 281-FREE FUN (281-373-3386) | milleroutdoortheatre.com Photo by Nash Baker INFORMATION Picnics Location A picnic on the hill is a tradition at Miller. Bring your own or purchase food 6000 Hermann Park Drive, Houston, TX 77030 and beverages from the Miller concession stand and help support the theatre: credit cards only. Go to milleroutdoortheatre.com for a complete menu. Something for Everyone Glass containers are prohibited in all City of Houston parks. If you are seated Miller offers the most diverse season of professional entertainment of any Houston in the covered seating area, please ensure that your cooler is small enough to performance venue — musical theater, traditional and contemporary dance, opera, fit under your seat in case an emergency exit is required. classical and popular music, multicultural performances, daytime shows for young audiences, and more! Oh, and it’s always FREE! Smoking Smoking is prohibited in Hermann Park and at Miller Outdoor Theatre, including Seating the hill. Tickets for evening performances are available online!! Tickets will be available at milleroutdoortheatre.com beginning at 9 a.m., one week prior to the performance Recording, Photography, & Remote Controlled Vehicles date until noon on the day of performance. All seating will be socially distanced. Audio/visual recording and/or photography of any portion of Miller Outdoor Theatre Seating is extremely limited due to COVID-19 capacity restrictions. All ticket holders presentations require the express written consent of the City of Houston. Launching, will have temperatures checked prior to entry to the covered seating area. landing, or operating unmanned or remote controlled vehicles (such as drones, quadcopters, etc.) within Miller Outdoor Theatre grounds— including the hill and Face coverings/masks are required for all attendees.. -

List of Religious Holidays Permitting Student Absence from School

Adoption Resolution May 5, 2021 RESOLUTION The List of Religious Holidays Permitting Student Absence from School WHEREAS, according to N.J.S.A. 18A:36-14 through 16 and N.J.A.C. 6A:32-8.3(j), regarding student absence from school because of religious holidays, the Commissioner of Education, with the approval of the State Board of Education, is charged with the responsibility of prescribing such rules and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the purpose of the law; and WHEREAS, the law provides that: 1. Any student absent from school because of a religious holiday may not be deprived of any award or of eligibility or opportunity to compete for any award because of such absence; 2. Students who miss a test or examination because of absence on a religious holiday must be given the right to take an alternate test or examination; 3. To be entitled to the privileges set forth above, the student must present a written excuse signed by a parent or person standing in place of a parent; 4. Any absence because of a religious holiday must be recorded in the school register or in any group or class attendance record as an excused absence; 5. Such absence must not be recorded on any transcript or application or employment form or on any similar form; and 6. The Commissioner, with the approval of the State Board of Education, is required to: (a) prescribe such rules and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the purposes of this act; and (b) prepare a list of religious holidays on which it shall be mandatory to excuse a student. -

Examining the Relationship Between Human Sexuality Training and Therapist Comfort with Addressing Sexuality with Clients

Smith ScholarWorks Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2011 Examining the relationship between human sexuality training and therapist comfort with addressing sexuality with clients Cari Lee Merritt Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Merritt, Cari Lee, "Examining the relationship between human sexuality training and therapist comfort with addressing sexuality with clients" (2011). Masters Thesis, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/549 This Masters Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cari Donovan Examining the Relationship between Human Sexuality Training and Therapist Comfort with Addressing Sexuality with Clients ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between human sexuality training and clinical social workers’ comfort with addressing sexuality issues with clients. A mixed methods survey was responded to by 90 participants who had graduated from Smith SSW between the years 2000 and 2009. Participants were asked questions pertaining to their level of comfort with discussions about sexuality; their attitudes about sexuality; and their knowledge and comfort with issues regarding erotic transference. The results of this study indicate that participants who received human sexuality training had a greater degree of comfort with discussing sexuality issues with their clients than those who had not received training. Respondents who had received some sort of human sexuality training reported that they initiate sexuality related discussions with clients and viewed such discussions as necessary more often than those with no training. -

The Application of Sexual Social Exchange Theory to Date Rape

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Psychology Psychology 2013 Great Sexpectations: The Application of Sexual Social Exchange Theory to Date Rape Kellie R. Lynch University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lynch, Kellie R., "Great Sexpectations: The Application of Sexual Social Exchange Theory to Date Rape" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--Psychology. 18. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/psychology_etds/18 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Psychology by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Evolutionary and Psychological Insights Into the Suppression of Female Sexuality

Evolutionary and psychological insights into the suppression of female sexuality Dax Joseph Kellie A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Evolution & Ecology Research Centre School of Biological, Earth, and Environmental Sciences Faculty of Science September 2019 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Kellie First Name: Dax Other name/s: Joseph Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: School of Biological, Earth & Environmental Sciences; Faculty: Science Evolution & Ecology Research Centre Title: Evolutionary and psychological insights into the suppression of female sexuality Abstract 350 words maximum: A number of competing theories spanning multiple disciplines currently exist on who restricts female sexuality, most positing that men, and some positing that women are responsible for its suppression. In this thesis, I explore female sexual suppression, drawing from current multiple evolutionary and psychological theories, to understand who may benefit from female sexual suppression. In Experiment 1, I investigated whether men and women anticipate lying more often to their family, friends, colleagues, acquaintances or partners about their sexual history. I find that women and men tell their biggest and most frequent lies to their parents, especially women to their fathers, suggesting parents strongly enforce sexual restriction on their daughters. In Chapters 3 and 4 I investigate which appearance-based judgements increase men and women’s objectifying perceptions of others. Results show that while positive judgements of women’s attractiveness can mitigate negative perceptions of them, negative judgements of women pursuing casual sex increase men and women’s objectification.