Choppin It up Lawrence BW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What a Caused Quite a Chuckle Since Being Released Online a Few Weeks Back

LAUGHING STOCK BY ED CHRISTMAN ® Inspired by the daytime talk show "Maury," where paternity tests are re- vealed on -air, rapper Shawty Putt's comical single "Dat Baby (Don't Look Like Me)," produced by Lil Jon, has What A caused quite a chuckle since being released online a few weeks back. With minimal promotion, the track Exclusive Journe from the Atlanta native's currently un- releases from Best Buy, left, and titled debut album entered the Bub- Journey! Wal -Mart sold 126,000 copies combined. bling Under R &B /Hip -Hop Singles Exclusive Deals Propel The results have been nothing short opted to make lemons into lemonade. ered on YouTube]." chart nine weeks ago at No. 24. It is Classic Rockers Up of spectacular: Sources say it sold In addition to the Best Buy exclusive, The Wal -Mart package acknowl- currently No. 5 on the tally as well as The Charts 28,000 on street date and, according the label put the Journey catalog on edges the material has been re- No. 34 on the Rap Airplay chart. to Nielsen SoundScan, moved almost deal, using its usual tactic of offering recorded and shows a picture of the The accompanying video has al- It's been a long time since retail has 105,000 in its first week, good enough discounts aligned with how much re- band with IDs for the members. So ready garnered more than 1 million rolled out the red carpet for Journey, for a No. 5 debut on the Billboard 200. tail was willing to do for a promotion. -

Army Recently, Saying Deserved Heroes' Welcome When They Re- Was to Free Kuwait

Point of honor 93rd Evacuation Hospital claims record in setting up for Operation Desert Storm By Bill Roche was one of them. He said that while at Camp ESSAYONS Contributor Shelby, the members of the 93rd had only one chance to set up the On the face of it, the 93rd Evacuation Hos- 384-bed DEPMEDS. It was difficult, pital's mission during Operation Desert he said, but ultimately it was enough. Storm sounds routine: provide medical sup- "In Saudi, it was hard to remember port to the 82nd Airborne Division. how (to set it up) at first, but we got But ask the unit to carry out their mission better," he said. with an entirely new hospital configuration, So much better, claimed his commander, and ask them to augment their ranks with Col. George Sampson, that of the five evacua- personnel they've never met, and it doesn't tion hospitals supporting the XVIIIth Air- sound so simple any more. borne Corps, the 93rd set up its DEPMEDS The 93rd is a Medical Unit, Self-contained fastest, and was operational in record time. Transportable (MUST) hospital outfit. Its nor- Sgt. Kevin Harris, an operating room spe- mal field hospital facility is made up of a se- cialist, heard that claim as well. "I heard we ries of inflatable quonset hut-like wards kept set up fastest of any hospital in the theater," erect by huge, jet fuel-powered blowers. he said. "Of course, I can't verify that." When not in use, the 93rd keeps its blow-up But Harris added that it was teamwork, not hospital packed in shipping containers, ready speed, that was important. -

Leisure Guide

LEISURE 23_5_18.qxp_Layout 1 17/05/2018 10:40 Page 1 Leisure Guide PRIZE Thesp’s Theatre Talk CROSSWORD CRYPTIC CLUES: OPERA BOYS COMING TO CREWE ACROSS DOWN 1 Day starts and finishes 1 Questionnaires about eading men from For the last 5 years The Making opera accessible to Song Contest, performing to a among pals (7) fashions (5) 5 Novice and expert died 2 Fashionable Northern London’s West End Opera Boys have been delighting the masses, The Opera Boys global audience of 200 million, intertwined (5) hostelry (3) combine in a audiences all over the world with combine their exceptional and placing a very respectable 8 Performance that has one in 3 Not one or the other is in Lpowerhouse of vocal their unique show combining classically trained voices with 4th in the competition! dirt (9) 9 Mr Thumb is half a drum (3) there (7) harmony to deliver a beautiful, powerful and their experience, showmanship Together the boys have 4 Holds on to some wood (6) 10 Cut some lovers’ initials on stunning blend of music emotional music with funny, and personality to deliver a performed in theatres and tree (5) 5 He needs to take on a great 12 King has old wizard tossed deal to become a knight (5) ranging from Opera to Pop, engaging and light-hearted wonderfully entertaining show concert halls throughout the UK into Russian citadel (7) 6 Directory contains a clue: and everything in between. entertainment. not to be missed! and have been lucky enough to 13 Singers heard among the goat is confused (9) The boys trained at some of travel all over the world paper (6) 7 Calls for Mad Ned’s the UK’s finest schools including performing their show. -

Middlebrow Mystics: Henri Bergson and British Culture, 1899-1939

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Green, Helen (2015) Middlebrow Mystics: Henri Bergson and British Culture, 1899-1939. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/27319/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html Middlebrow Mystics: Henri Bergson and British Culture, 1899-1939 Helen L. Green PhD 2015 Middlebrow Mystics: Henri Bergson and British Culture, 1899-1939 Helen Louise Green A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design and Social Sciences. May 2015 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. -

Ts'msyen Revolution: the Op Etics and Politics of Reclaiming Robin R

University of Massachusetts - Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 2014-current Dissertations and Theses 2015 Ts'msyen Revolution: The oP etics and Politics of Reclaiming Robin R. R. Gray Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 2014-current by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TS’MSYEN REVOLUTION: THE POETICS AND POLITICS OF RECLAIMING A Dissertation Presented By ROBIN R. R. GRAY (T’UU’TK) Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2015 Department of Anthropology © Copyright by Robin R. R. Gray (T’uu’tk) 2015 All Rights Reserved TS’MSYEN REVOLUTION: THE POETICS AND POLITICS OF RECLAIMING A Dissertation Presented By ROBIN R. R. GRAY (T’UU’TK) Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________________ Jane Anderson, Chair _____________________________________________ Sonya Atalay, Chair _____________________________________________ Demetria Shabazz, Member __________________________________________ Thomas Leatherman, Department Chair Department of Anthropology DEDICATION To the Nine Allied Tribes and the people of Lax Kw’alaams—past, present and future. In honor of my late grandmothers—through them my family has a place to stand in Waap Liyaa’mlaxha, Gisbutwada, Gitaxangiik. We reclaim to honor their lives. My grandmother Norah Rita Gray, My great-grandmother Elizabeth nee Gulbrandsen, nee Wright Dorothy Gulbrandsen, nee Wright, (1937 – 1977) nee Moody (1905 – 1983) Finally, dedicated to one of my research partners and teachers from Lax Kw’alaams—the late Smooygit Xyuup, Wayne Ryan (1930-2013). -

2015 Annual Magazine

Junior School 120 Junior School headmistress’ address 120 Goodbye 123 Academic staff 124 Administrative staff 125 The Open Door team 125 Little Saints 126 Grade classes 128 Grade 7 memories 170 Grade 0-7 171 Grahamstown 2015 171 Grade 4 tour 172 Grade 5 tour 173 Grade 6 tour 174 Grade 7 tour 175 Environmental club 176 Chess club 176 Nativity play 177 Junior Primary production 178 Senior Primary production 180 Music 182 Sports 186 The St Mary’s Foundation 192 Community affairs 194 Parent Teacher Association 202 St Mary’s Old Girls’ Association 206 School prayer 212 2 Chairman’s address Prizegiving address by Nigel Carman 16 October 2015 To our guest of honour, Mr Frederick Swaniker, founder and and enthusiasm, and for the diverse special skills and experience chairperson of the African Leadership Academy, Ms Deanne which each of you brings so willingly for the benefit of the school. King, head of St Mary’s, Mrs Des Hugo and the staff of St Mary’s, colleagues on the Board of the school, and on the Board of the Last year, on this occasion, I asked the question: so what makes St Mary’s Foundation, parents, a great school? How do we know friends, girls of St Mary’s and most when we have been successful? Is it especially, the matric class of 2015 sufficient to have excellent matric – welcome to this assembly of the and sporting results? Or is it about school in celebration of the year the sort of people we help the girls that is drawing to a close and the to become when they leave the achievements of many girls who, school? in one way or another, and on their own terms, have excelled. -

Coventry & Warwickshire Cover

Coventry & Warwickshire Cover November 2017 .qxp_Coventry & Warwickshire Cover 20/10/2017 15:20 Page 1 KATHERINE RYAN AT COVENTRY & WARWICKSHIRE WHAT’S ON NOVEMBER 2017 2017 ON NOVEMBER WHAT’S WARWICKSHIRE & COVENTRY Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands WARWICK ARTS CENTRE Coventry & Warwickshire ISSUE 383 NOVEMBER 2017 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On warwickshirewhatson.co.uk PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART TWITTER: @WHATSONWARWICKS @WHATSONWARWICKS FACEBOOK: @WHATSONWARWICKSHIRE WARWICKSHIREWHATSON.CO.UK (IFC) Warwickshire.qxp_Layout 1 23/10/2017 17:46 Page 1 Contents November Warwicks_Worcs.qxp_Layout 1 23/10/2017 17:29 Page 2 November 2017 Contents The Hairy Bikers - cook up a treat at the BBC Good Food Show - page 49 Alison Moyet Patrick Monahan The Stick Man the list stops off at Warwick Arts Centre headlines the Desi Central children’s favourite visits Your 16-page to promote new album Other Comedy Show at the Belgrade Malvern Theatres week-by-week listings guide page 15 page 23 page 30 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 15. Music 22. Comedy 24. Theatre 40. Film 44. Visual Arts 47. Events fb.com/whatsonwarwickshire fb.com/whatsonworcestershire @whatsonwarwicks @whatsonworcs Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Managing Director: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 -

Literary Theory, an Introduction Second Edition

Literary Theory Second Edition For Charles Swann and Raymond Williams Literary Theory An Introduction SECOND EDITION Terry Eagleton St Catherine '5 College Oxford Blackwell Publishing © 1983,1996 by Terry Eagleton BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020,USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Terry Eagleton to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, . photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 1983 Second edition 1996 10 2005 Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Eagleton, Terry, 1943- Literary Theory: an introduction / Terry Eagleton - 2nd ed. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-20188-2 (pbk: alk. paper) 1. Criticism-History-20th Century. 2. Literature-History and criticism- Theory, etc. 1.Title PN94.E2 1996 96-4572 801'.95'0904-dc20 CIP ISBN-13:978-0-631-20188-5(pbk: alk. paper) A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10.5 on 12.5 pt Ehrhardt by Best-set Typesetter Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt Ltd, Kundli The publisher's policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. -

Specials Under $10!!!

Specials Under $10!!! 8 Mile (2002) DVD M Drama Cat#: 8200676 RRP $19.95 SALE $9.45 ☺ 8 Mile explores a week in the lives of a group of young people struggling to find their way in the urban decay of 1995 Detroit. For people like Jimmy ... Ε Eminem, Kim Basinger, Brittany Murphy, Mekhi Phifer Ali (2001) DVD M Drama Cat#: R-108340-9 RRP $19.95 SALE $9.45 ☺ Loved, reviled, underestimated and oversimplified, Muhammad Ali was anything but ordinary. One thing though was indisputable: he was "The Greatest". This ... Ε Will Smith, Jamie Foxx, Jon Voight, Mario Van Peebles, Jeffrey Wright, Mykelti Williamson, Jada Pinkett Smith Amelia (2009) DVD PG Drama Cat#: 41780SDO RRP $39.95 SALE $9.45 ☺ An extraordinary life of adventure, celebrity and continuing mystery comes to light in Amelia, a vast, thrilling account of legendary aviation pioneer ... Ε Hilary Swank, Richard Gere, Ewan McGregor Blindness (2008) DVD MA15+ Drama Cat#: R-107543-9 RRP $19.95 SALE $9.45 ☺ A city is ravaged by an epidemic of instant "white blindness". Those first afflicted are quarantined by the authorities in an abandoned mental hospital ... Ε Mark Ruffalo, Julianne Moore Blow (2000) DVD MA15+ Drama Cat#: R-103241-9 RRP $19.95 SALE $9.45 ☺ He was just a small town boy who became the most powerful drug lord in the United States. His name was George Jung, the man first responsible for bringing ... Ε Johnny Depp, Penelope Cruz, Franka Potente, Rachel Griffiths, Ray Liotta, Paul Reubens Boogie Nights (1998) DVD R18+ Drama Cat#: R-101728-9 RRP $19.95 SALE $9.45 ☺ In 1977, a kid from nowhere had a dream of becoming somebody. -

3. Literary Theory: an Introduction, Terry Eagleton

Literary Theory For Charles Swann and Raymond Williams Literary Theory An Introduction SECOND EDITION Terry Eagleton Copyright Terry Eagleton 1983, 1996 First published in this second edition in Great Britain by Blackwell Publishers Ltd. First published in 1996 in this second edition in the United States by The University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Fourth printing, 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, widiout the prior written permission of die publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Eagleton, Terry, 1943- Literary theory: an introduction / Terry Eagleton. - 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8166-1251-X (pbk: alk paper) 1. Criticism—History—20th century. 2. Literature—History and criticism—Theory, etc. I. Tide PN94.E2 1996 801'.95'0904 —dc20 Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Preface to the Second Edition vii Preface ix Introduction: What is Literature? 1 1 The Rise of English 15 2 Phenomenology, Hermeneutics, Reception Theory 47 3 Structuralism and Semiotics 79 4 Post-Structuralism 110 5 Psychoanalysis 131 Conclusion: Political Criticism 169 Afterword 190 Notes 209 Bibliography 217 Index 224 This page intentionally left blank Preface to the Second Edition This book is an attempt to make modern literary theory intelligible and attractive to as wide a readership as possible. -

Synopsis CPL 1

General and PG titles Call: 1-800-565-1996 Criterion Pictures 30 MacIntosh Blvd., Unit 7 • Vaughan, Ontario • L4K 4P1 800-565-1996 Fax: 866-664-7545 • www.criterionpic.com 10,000 B.C. 2008 • 108 minutes • Colour • Warner Brothers Director: Roland Emmerich Cast: Nathanael Baring, Tim Barlow, Camilla Belle, Cliff Curtis, Joel Fry, Mona Hammond, Marco Khan, Reece Ritchie A prehistoric epic that follows a young mammoth hunter's journey through uncharted territory to secure the future of his tribe. The 11th Hour 2007 • 93 minutes • Colour • Warner Independent Pictures Director: Leila Conners Petersen, Nadia Conners Cast: Leonardo DiCaprio (narrated by) A look at the state of the global environment including visionary and practical solutions for restoring the planet's ecosystems. 13 Conversations About One Thing 2001 • 102 minutes • Colour • Mongrel Media Director: Jill Sprecher Cast: Matthew McConaughey, David Connolly, Joseph Siravo, A.D. Miles, Sig Libowitz, James Yaegashi In New York City, the lives of a lawyer, an actuary, a house-cleaner, a professor, and the people around them intersect as they ponder order and happiness in the face. of life's cold unpredictability. 16 Blocks 2006 • 102 minutes • Colour • Warner Brothers Director: Richard Donner Cast: Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David Morse, Alfre Woodard, Nick Alachiotis, Brian Andersson, Robert Bizik, Shon Blotzer, Cylk Cozart Based on a pitch by Richard Wenk, the mismatched buddy film follows a troubled NYPD officer who's forced to take a happy, but down-on- his-luck witness 16 blocks from the police station to 100 Centre Street, although no one wants the duo to make it. -

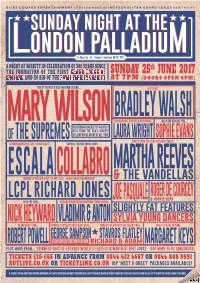

Collabro Escala

GILES COOPER ENTERTAINMENT LTD BY ARRANGEMENT WITH METROPOLITAN GRAND LODGE PROUDLY PRESENTS eeeeSUNDAYSUNDAY NIGHTNIGHT ATAT THETHEeeee LL ONDONONDON PALLADIUPALLADIUMM 8 Argyll St, Soho, London W1F 7TE A NIGHT OF VARIETY IN CELEBRATION OF 300 YEARS SINCE th THE FORMATION OF THE FIRST GRAND LODGE OF SUNDAY 25 JUNE 2017 ENGLAND AND IN AID OF THE ROYAL VARIETY CHARITY AT 7PM (DOORS OPEN 6PM) DIRECT FROM THE USA! MOTOWN LEGEND... HOSTED BY... BRADLEY WALSH MARY WILSON CLASSICAL NUMBER 1 ALBUM SELLING MEZZO SOPRANO... WEST-END MUSICAL STAR... PERFORMING A MEDLEY OF GREATEST HITS FROM THE USA’S BIGGEST of the supremes SELLING VOCAL GROUP OF ALL-TIME LAURA WRIGHT SOPHIE EVANS DIRECT FROM THE USA! MOTOWN LEGEND... GROUNDBREAKING ELECTRIC STRING QUARTET... MUSICAL THEATRE SUPER-GROUP... ESCALA COLLABRO MARTHA REEVES WINNER OF BRITAIN’S GOT TALENT 2016... MAGICIAN EXTRAORDINAIRE! & THE VANDELLAS LCPL RICHARD JONES roger de courcey & nookie bear 80’S POP ICON... ‘DUELLING’ VIOLIN VIRTUOSO BROTHERS FROM SLOVAKIA... SLIGHTLY FAT FEATURES NICK HEYWARD VLADIMIR & ANTON SYLVIA YOUNG DANCERS TV AND MOVIE STAR... WINNER OF BRITAIN’S GOT TALENT 2008... FINALISTS OF BRITAIN’S GOT TALENT 2009... IRISH CLASSICAL SOPRANO... GEORGE SAMPSON STAVROS FLATLEY ROBERT POWELL FINALISTS OF BRITAIN’S GOT TALENT 2013... RICHARD & ADAM MARGARET KEYS PLUS MORE FROM... GUINNESS BOOK OF RECORDS WORLD’S FASTEST HUMAN BEAT BOX! JC001 · AND MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED! TICKETS £15-£65 IN ADVANCE FROM 0844 412 4657 OR 0844 888 9991 RUTLIVE.CO.UK OR TICKETLINE.CO.UK VIP ‘MEET & GREET’ PACKAGES AVAILABLE! ALL PROCEEDS TO THE ROYAL VARIETY CHARITY (REGISTERED CHARITY NUMBER 206451) AND THE METROPOLITAN GRAND CHARITY’S TERCENTENARY APPEAL | SUBJECT TO AVAILABILITY.