Bill Williams River NWR Draft Hunting and Fishing EA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona Fishing Regulations 3 Fishing License Fees Getting Started

2019 & 2020 Fishing Regulations for your boat for your boat See how much you could savegeico.com on boat | 1-800-865-4846insurance. | Local Offi ce geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | Local Offi ce See how much you could save on boat insurance. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. TowBoatU.S. is the preferred towing service provider for GEICO Marine Insurance. The GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2017. © 2017 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 2 12/4/2018 1:14:48 PM AdPages2019.indd 3 12/4/2018 1:17:19 PM Table of Contents Getting Started License Information and Fees ..........................................3 Douglas A. Ducey Governor Regulation Changes ...........................................................4 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH COMMISSION How to Use This Booklet ...................................................5 JAMES S. ZIELER, CHAIR — St. Johns ERIC S. SPARKS — Tucson General Statewide Fishing Regulations KURT R. DAVIS — Phoenix LELAND S. “BILL” BRAKE — Elgin Bag and Possession Limits ................................................6 JAMES R. AMMONS — Yuma Statewide Fishing Regulations ..........................................7 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT Common Violations ...........................................................8 5000 W. Carefree Highway Live Baitfish -

Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona

Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1360-D DEC 10 1956 Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona By H. N. WOLCOTT, H. E. SKIBITZKE, and L. C. HALPENNY CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1360-D An investigation of the availability of water in the area of the Artillery Mountains manganese deposits UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1956 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 45 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract....................................................................................................................................... 291 Introduction................................................................................................................................. 292 Purpose.................................................................................................................................... 292 Location................................................................................................................................... 292 Climatological data............................................................................................................... 292 History of development........................................................................................................ -

Movements of Sonic Tagged Razorback Suckers Between Davis and Parker Dams (Lake Havasu) 2007–2010

Movements of Sonic Tagged Razorback Suckers between Davis and Parker Dams (Lake Havasu) 2007–2010 May 2012 Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Program Steering Committee Members Federal Participant Group California Participant Group Bureau of Reclamation California Department of Fish and Game U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service City of Needles National Park Service Coachella Valley Water District Bureau of Land Management Colorado River Board of California Bureau of Indian Affairs Bard Water District Western Area Power Administration Imperial Irrigation District Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Palo Verde Irrigation District Arizona Participant Group San Diego County Water Authority Southern California Edison Company Arizona Department of Water Resources Southern California Public Power Authority Arizona Electric Power Cooperative, Inc. The Metropolitan Water District of Southern Arizona Game and Fish Department California Arizona Power Authority Central Arizona Water Conservation District Cibola Valley Irrigation and Drainage District Nevada Participant Group City of Bullhead City City of Lake Havasu City Colorado River Commission of Nevada City of Mesa Nevada Department of Wildlife City of Somerton Southern Nevada Water Authority City of Yuma Colorado River Commission Power Users Electrical District No. 3, Pinal County, Arizona Basic Water Company Golden Shores Water Conservation District Mohave County Water Authority Mohave Valley Irrigation and Drainage District Native American Participant Group Mohave Water Conservation District North Gila Valley Irrigation and Drainage District Hualapai Tribe Town of Fredonia Colorado River Indian Tribes Town of Thatcher Chemehuevi Indian Tribe Town of Wickenburg Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District Unit “B” Irrigation and Drainage District Conservation Participant Group Wellton-Mohawk Irrigation and Drainage District Yuma County Water Users’ Association Ducks Unlimited Yuma Irrigation District Lower Colorado River RC&D Area, Inc. -

Razorback Suckers Are Making a Comeback in the Upper Colorado River Basin

Winter 13 Razorback suckers are making a comeback in the upper Colorado River basin iologists are thrilled that the recovery programs’ stocking Hatchery programs have been very successful. In the upper efforts are bearing fruit and razorback suckers are becom- basin, razorback suckers are being raised by the Ouray National Bing more numerous throughout the upper Colorado River Fish Hatchery, Randlett and Grand Valley units near Vernal, Utah basin. “We catch so many razorbacks these days; it takes us lon- and Grand Junction, Colorado. Following analysis of razorback ger to complete our Colorado pikeminnow sampling trips,” says sucker stocking and survival by Colorado State University’s Larval U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) researcher Travis Francis. Fish Lab, the Recovery Program increased the size of razorback Historically, the razorback sucker occurred throughout warm- sucker for stocking from an average of about 11 inches to about 14 water reaches of the Colorado River Basin from Mexico to Wyoming. PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY UDWR-MOAB inches and is stocking the fish in the fall when fish survive better. When this species was listed in 1991, its numbers were much reduced To increase growth, the Program raises the fish in a combination and biologists were worried it might become extinct. Thanks to of outdoor ponds during warmer months and indoor tanks in the the efforts of the San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation winter. Program and the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery This past summer, many wild-spawned razorback larvae drift- Program, these fish are making a real comeback today. Hatchery- ed from a middle Green River spawning bar into the Stewart Lake produced fish are being stocked to re-establish the species in the JUVENILE RAZORBACK SUCKER, MAY, 2013 wetland about 11 miles downstream. -

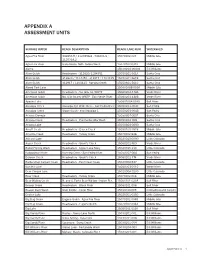

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Fishes As a Template for Reticulate Evolution

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Fishes as a Template for Reticulate Evolution: A Case Study Involving Catostomus in the Colorado River Basin of Western North America Max Russell Bangs University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Evolution Commons, Molecular Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Bangs, Max Russell, "Fishes as a Template for Reticulate Evolution: A Case Study Involving Catostomus in the Colorado River Basin of Western North America" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1847. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fishes as a Template for Reticulate Evolution: A Case Study Involving Catostomus in the Colorado River Basin of Western North America A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology by Max Russell Bangs University of South Carolina Bachelor of Science in Biological Sciences, 2009 University of South Carolina Master of Science in Integrative Biology, 2011 December 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _____________________________________ Dr. Michael E. Douglas Dissertation Director _____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Marlis R. Douglas Dr. Andrew J. Alverson Dissertation Co-Director Committee Member _____________________________________ Dr. Thomas F. Turner Ex-Officio Member Abstract Hybridization is neither simplistic nor phylogenetically constrained, and post hoc introgression can have profound evolutionary effects. -

March 1988 Vol

March 1988 Vol. XIII No. 3 Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Technical Bulletin Service, Washington, D.C. 20204 Help Is On the Way for Rare Fishes of the Upper Colorado River Basin Sharon Rose and John Hamill Denver Regional Office On January 21-22, 1988, the Governors of Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah joined Secretary of the Interior Model and the Administrator of the Western Area Power Administration in signing a cooperative agreement to implement a recovery pro- gram for rare and endangered species of fish in the Upper Colorado River Basin. The recovery program is a milestone effort that coordinates Federal, State, and private actions to conserve the fish in a manner compatible with States' water rights allocation systems and the various interstate compacts that guide water al- location, development, and management in the Upper Colorado River Basin. The Colorado River is over 1,400 miles long, passes through two countries, and has a drainage basin of 242,000 square miles in the United States, yet it provides less water per square mile in its basin than any other major river system in the United States. Demands on this limited resource are high. The Colorado River serves 15 million people by supplying water for irrigation, hydroelectric power generation, industrial and municipal pur- poses, recreation, and fish and wildlife enhancement. The headwater streams of the Upper Colorado River originate in the Rocky and Uinta Mountains. Downstream, the main- stem river historically was characterized by silty, turbulent flows with large varia- tions in annual discharge. The native warmwater fishes adapted to this de- manding environment; however, to meet 'J. -

The Colorado River: Lifeline Of

4 The Colorado River: lifeline of the American Southwest Clarence A. Carlson Department of Fishery and Wildlife Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523 Robert T. Muth Larval Fish Laboratory, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523 1 Carlson, C. A., and R. T. Muth. 1986. The Colorado River: lifeline of the American Southwest. Can. J. Fish. Aguat. Sci. In less than a century, the wild Colorado River has been drastically and irreversibly transformed into a tamed, man-made system of regulated segments dominated by non-native organisms. The pristine Colorado was characterized by widely fluctuating flows and physico-chemical extremes and harbored unique assemblages of indigenous flora and fauna. Closure of Hoover Dam in 1935 marked the end of the free-flowing river. The Colorado River System has since become one of the most altered and intensively controlled in the United States. Many main-stem and tributary dams, water diversions, and channelized river sections now exist in the basin. Despite having one of - the most arid drainages in the world, the present-day Colorado River supplies more water for consumptive use than any river in the United States. Physical modification of streams and introduction of non-native species have adversely impacted the Colorado's native biota. This paper treats the Colorado River holistically as an ecosystem and summarizes current knowledge on its ecology and management. "In a little over two generations, the wild Colorado has been harnessed by a series of dams strung like beads on a thread from the Gulf of California to the mountains of Wyoming. -

Analysis of Sediment Dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona

Analysis of sediment dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona Andrew C. Wilcox and Franklin Dekker Department of Geosciences Center for Riverine Science and Stream Renaturalization University of Montana Missoula, MT 59812-1296 Paul Gremillion (Northern Arizona University) and David Walker (University of Arizona) Collaborators: Patrick Shafroth (USGS), Cliff Riebe (University of Wyoming), Kyle House (USGS), John Stella (State University of New York) Report prepared for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, via Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) February 6, 2013 DRAFT FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 Catchment Erosion Rates and Sediment Mixing in a Dammed Dryland River ............................. 11 Dryland River Grain-Size Variation due to Damming, Tributary Confluences, and Valley Confinement ................................................................................................................................. 28 Analysis of Sediment Dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona: Hydroacoustic Surveys and Sediment Coring ............................................................................................................................ 46 Coupled Hydrogeomorphic and Woody-Seedling Responses to Controlled Flood -

Salinity of Surface Water in the Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area

Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River- Salton Sea Area By BURDGE IRELAN WATER RESOURCES OF LOWER COLORADO RIVER SALTON SEA AREA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72 610761 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Price 50 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract . _.._.-_. ._...._ ..._ _-...._ ...._. ._.._... El Ionic budget of the Colorado River from Lees Ferry to Introduction .._____. ..... .._..__-. - ._...-._..__..._ _.-_ ._... 2 Imperial Dam, 1961-65 Continued General chemical characteristics of Colorado River Tapeats Creek .._________________.____.___-._____. _ E26 water from Lees Ferry to Imperial Dam ____________ 2 Havasu Creek __._____________-...- _ __ -26 Lees Ferry .._._..__.___.______.__________ 4 Virgin River ..__ .-.._..-_ --....-. ._. 26 Grand Canyon ................._____________________..............._... 6 Unmeasured inflow between Grand Canyon and Hoover Dam ..........._._..- -_-._-._................-._._._._... 8 Hoover Dam .__-.....-_ .... .-_ . _. 26 Lake Havasu - -_......_....-..-........ .........._............._.... 11 Chemical changes in Lake Mead ............-... .-.....-..... 26 Imperial Dam .--. ........_. ...___.-_.___ _.__.__.._-_._.___ _ 12 Bill Williams River ......._.._......__.._....._ _......_._- 27 Mineral burden of the lower Colorado River, 1926-65 . -

Razorback Sucker (Xyrauchen Texanus) Recovery Plan

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) Depository) 1998 Razorback Sucker (Xyrauchen texanus) Recovery Plan Harold M. Tyus University of Colorado at Boulder Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons Recommended Citation Tyus, Harold M., "Razorback Sucker (Xyrauchen texanus) Recovery Plan" (1998). All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository). Paper 467. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs/467 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Razorback Sucker (Xyraucben texanus) Recovery Plan RAZORBACK SUCKER (Xyrauchen texanus) Recovery Plan Prepared by: Harold M. Tyus Center for Limnology University of Colorado at Boulder Boulder, CO 80309-0334 for Region 6 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Denver, Colorado Approved: Regiobal urector, ‘Regionjb, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service DISCLAIMER PAGE Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and or protect listed species. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service publishes these plans, which may be prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Attainment of the objectives, and provision of any necessary funds are subject to priorities, budgetary, and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. -

Supplemental Materials and Information: CRB Geography

Supplemental Materials and Information: CRB Geography Study Area Detail The 283,384 km2 Upper Colorado River Basin (UCRB) drains the West Slope of the Rocky Mountains and the stratigraphically largely undeformed Colorado Plateau section of the Rocky Mountains geologic province. Colorado Plateau strata range in age from early Proterozoic (1.84 billion years ago) metamorphic crystalline basement rock, to Precambrian through early Cenozoic sedimentary strata, with late Cenozoic basalts [32], and ranging in elevation from 4352 m down to 350 m on Lake Mead Reservoir. Every natural CRB tributary we have examined thus far arises from springs, springfed wetlands, or small groundwater-fed lakes e.g., [21]. For example, UCRB mainstream flow arises from two primary sources [12,13]. The 1112 km-long Green River sources at an unnamed springfed fen 2 km southwest of Mt. Wilson in the Wind River Range in Sublette County, Wyoming, and also receives surface snowmelt water from Minor Glacier and other snowfields near Gannet Peak (4087 m). Along its course, the Green River receives flow from the Yampa and White Rivers, and delivers a long-term mean discharge at its mouth of 173 m3/sec. Similarly, the upper Colorado River similarly arises from a springfed fen at La Poudre Pass in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, and receives flow downstream from the Gunnison, Dolores, and other rivers and streams [13]. Downstream from the Green and Colorado Rivers confluence in Canyonlands National Park, Utah the mainstream is joined by the flows of: the Fremont/Muddy, San Juan, and Escalante Rivers in Lake Powell Reservoir, and the Paria River near Lees Ferry, Arizona.