January 3, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

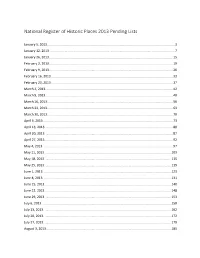

National Register of Historic Places 2013 Pending Lists

National Register of Historic Places 2013 Pending Lists January 5, 2013. ............................................................................................................................................ 3 January 12, 2013. .......................................................................................................................................... 7 January 26, 2013. ........................................................................................................................................ 15 February 2, 2013. ........................................................................................................................................ 19 February 9, 2013. ........................................................................................................................................ 26 February 16, 2013. ...................................................................................................................................... 33 February 23, 2013. ...................................................................................................................................... 37 March 2, 2013. ............................................................................................................................................ 42 March 9, 2013. ............................................................................................................................................ 48 March 16, 2013. ......................................................................................................................................... -

2019 Most Endangered Historic Places in Illinois

2019 MOST ENDANGERED HISTORIC PLACES IN ILLINOIS 1 12 4 9 5 6 2 8 1 Greek Housing at James R. Thompson Center 3 Chicago, Cook County University of Illinois Urbana, Champaign County 10 2 11 Sheffield National Register Ray House Historic District Rushville, Schuyler County Chicago, Cook County 11 12 3 10 Washington Park National Bank Rock Island County Chicago, Cook County Courthouse Rock Island, Rock Island County 9 4 7 St. Mary’s School Chancery & Piety Hill Galena, Jo Daviess County Properties Rockford, Winnebago County 5 8 6 7 Booth Cottage Hill Motor Sales Building Glencoe, Cook County Oak Park, Cook County Hoover Estate Millstadt Milling & Feed Company Glencoe, Cook County Millstadt, St. Clair County LANDMARKS ILLINOIS 2019 Most Endangered Historic Places in Illinois JAMES R. THOMPSON CENTER MILLSTADT MILLING & FEED COMPANY 100 W Randolph Street, Chicago, Cook County 419 S Jefferson Street, Millstadt, St. Clair County For the third year in a row, LI is including the one-of-a-kind, state-owned Built in 1857 with a grain elevator added in 1880, the property is one of building in Chicago’s Loop on its Most Endangered list. Designed by the oldest continually operating grain elevators in the state and Helmut Jahn in 1985, the Thompson Center remains threatened as the represents a critical piece of Illinois’ industrial and agricultural past. State of Illinois continues to pursue a sale of the building that could allow Despite its historic significance and sound condition, Millstadt village new development on the site. In March 2019, Gov. JB Pritzker signed officials have declared the site a “public nuisance” and given the current legislation that outlines a two-year plan for the building’s sale. -

Rehabilitation of Galena's 1858 Historic Post Office and Customhouse: Relocation of the Galena-Jo Daviess Historical Society and Museum

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2003 Rehabilitation of Galena's 1858 historic post office and customhouse: relocation of the Galena-Jo Daviess Historical Society and Museum Matthew Thomas Lundh Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Lundh, Matthew Thomas, "Rehabilitation of Galena's 1858 historic post office and customhouse: relocation of the Galena-Jo Daviess Historical Society and Museum" (2003). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19489. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19489 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rehabilitation of Galena's 1858 historic Post Office and Customhouse: Relocation of the Galena-Jo Davies Historical Society and Museum by Matthew Thomas Lundh A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE Major: Architecture Program of Study, Committee: Bruce Basler, Major Professor Arvid Osterberg Robert Harvey Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2003 Copyright ©Matthew Thomas Lundh, 2003. A11 rights reserved. 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that -

List of National Register Properties

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES IN ILLINOIS (As of 11/9/2018) *NHL=National Historic Landmark *AD=Additional documentation received/approved by National Park Service *If a property is noted as DEMOLISHED, information indicates that it no longer stands but it has not been officially removed from the National Register. *Footnotes indicate the associated Multiple Property Submission (listing found at end of document) ADAMS COUNTY Camp Point F. D. Thomas House, 321 N. Ohio St. (7/28/1983) Clayton vicinity John Roy Site, address restricted (5/22/1978) Golden Exchange Bank, Quincy St. (2/12/1987) Golden vicinity Ebenezer Methodist Episcopal Chapel and Cemetery, northwest of Golden (6/4/1984) Mendon vicinity Lewis Round Barn, 2007 E. 1250th St. (1/29/2003) Payson vicinity Fall Creek Stone Arch Bridge, 1.2 miles northeast of Fall Creek-Payson Rd. (11/7/1996) Quincy Coca-Cola Bottling Company Building, 616 N. 24th St. (2/7/1997) Downtown Quincy Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire, Jersey, 4th & 8th Sts. (4/7/1983) Robert W. Gardner House, 613 Broadway St. (6/20/1979) S. J. Lesem Building, 135-137 N. 3rd St. (11/22/1999) Lock and Dam No. 21 Historic District32, 0.5 miles west of IL 57 (3/10/2004) Morgan-Wells House, 421 Jersey St. (11/16/1977) DEMOLISHED C. 2017 Richard F. Newcomb House, 1601 Maine St. (6/3/1982) One-Thirty North Eighth Building, 130 N. 8th St. (2/9/1984) Quincy East End Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire, 24th, State & 12th Sts. (11/14/1985) Quincy Northwest Historic District, roughly bounded by Broadway, N. -

National Register of Historic Places Single Property Listings Illinois

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES SINGLE PROPERTY LISTINGS ILLINOIS FINDING AID One LaSalle Street Building (One North LaSalle), Cook County, Illinois, 99001378 Photo by Susan Baldwin, Baldwin Historic Properties Prepared by National Park Service Intermountain Region Museum Services Program Tucson, Arizona May 2015 National Register of Historic Places – Single Property Listings - Illinois 2 National Register of Historic Places – Single Property Listings - Illinois Scope and Content Note: The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the official list of the Nation's historic places worthy of preservation. Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources. - From the National Register of Historic Places site: http://www.nps.gov/nr/about.htm The Single Property listing records from Illinois are comprised of nomination forms (signed, legal documents verifying the status of the properties as listed in the National Register) photographs, maps, correspondence, memorandums, and ephemera which document the efforts to recognize individual properties that are historically significant to their community and/or state. Arrangement: The Single Property listing records are arranged by county and therein alphabetically by property name. Within the physical files, researchers will find the records arranged in the following way: Nomination Form, Photographs, Maps, Correspondence, and then Other documentation. Extent: The NRHP Single Property Listings for Illinois totals 43 Linear Feet. Processing: The NRHP Single Property listing records for Illinois were processed and cataloged at the Intermountain Region Museum Services Center by Leslie Matthaei, Jessica Peters, Ryan Murray, Caitlin Godlewski, and Jennifer Newby. -

National Historic Landmarks Program

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS PROGRAM LIST OF NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS BY STATE July 2015 GEORGE WASHINGTOM MASONIC NATIONAL MEMORIAL, ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA (NHL, JULY 21, 2015) U. S. Department of the Interior NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS PROGRAM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE LISTING OF NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS BY STATE ALABAMA (38) ALABAMA (USS) (Battleship) ......................................................................................................................... 01/14/86 MOBILE, MOBILE COUNTY, ALABAMA APALACHICOLA FORT SITE ........................................................................................................................ 07/19/64 RUSSELL COUNTY, ALABAMA BARTON HALL ............................................................................................................................................... 11/07/73 COLBERT COUNTY, ALABAMA BETHEL BAPTIST CHURCH, PARSONAGE, AND GUARD HOUSE .......................................................... 04/05/05 BIRMINGHAM, JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA BOTTLE CREEK SITE UPDATED DOCUMENTATION 04/05/05 ...................................................................... 04/19/94 BALDWIN COUNTY, ALABAMA BROWN CHAPEL A.M.E. CHURCH .............................................................................................................. 12/09/97 SELMA, DALLAS COUNTY, ALABAMA CITY HALL ...................................................................................................................................................... 11/07/73 MOBILE, MOBILE COUNTY, -

US Route 20 (FAP 301) Jodaviess and Stephenson Counties

RECORD OF DECISION US Route 20 (FAP 301) JoDaviess and Stephenson Counties FHWA-IL-EIS-00-03-F September 22, 2005 1. BACKGROUND History: For more than forty years, a formal public interest in improving U.S. Route 20 in northwestern Illinois has been evident. The Illinois State Legislature, in 1963, established the Transportation Study Commission (TSC) in order to study statewide transportation system needs and develop a long-range program for improvements. A 1967 TSC report identified a freeway location between Dubuque, Iowa and Rockford, Illinois. This freeway location was in response to an identified need to provide access to adjacent interstates and to improve east-west traffic service in northwestern Illinois. The Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) continued detailed study of potential locations for the freeway during the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. The Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA) established a National Highway System (NHS) to continue the development of a prioritized national roadway network. The U.S. Route 20 is a NHS route, and this study was identified in ISTEA as a demonstration project. Purpose and Need: The purpose of the proposed action is to provide an improved transportation system in JoDaviess and Stephenson Counties, to provide a facility that will properly address existing and projected system deficiencies, and to improve the safety and efficiency of the existing roadway system. The proposed action will address the needs of accommodating continuing development, increasing inadequate system capacity, addressing travel safety, improving community access and providing system continuity. The growth in travel demand along existing U.S. -

City of Galena, Illinois

Page 1 of 101 City of Galena, Illinois AGENDA REGULAR CITY COUNCIL MEETING TUESDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2019 6:30 P.M. – CITY HALL 101 GREEN STREET ITEM DESCRIPTION 19C‐0400. Call to Order by Presiding Officer 19C‐0401. Roll Call 19C‐0402. Establishment of Quorum 19C‐0403. Pledge of Allegiance 19C‐0404. Reports of Standing Committees 19C‐0405. Citizens Comments Not to exceed 15 minutes as an agenda item Not more than 3 minutes per speaker PUBLIC HEARINGS None. LIQUOR COMMISSION None. CONSENT AGENDA CA19‐21 ITEM DESCRIPTION PAGE 19C‐0406. Approval of the Minutes of the Regular City Council Meeting of September 23, 4‐8 2019 19C‐0407. Approval of Budget Amendment BA20‐06 for Waterworks Sidewalk Construction 9‐10 and Gear Street Project Costs 19C‐0408. Approval of Galena Balloon Glow on the East and West Side Levee (Ground 11‐12 Conditions Permitting) on Friday, October 25 from 6:00 P.M. to 9:00 P.M. 19C‐0409. Approval of Revised Site Boundaries for School Section Archery Deer Hunting 13‐14 Site Page 1 of 3 Page 2 of 101 UNFINISHED BUSINESS ITEM DESCRIPTION PAGE 17C‐0322. Discussion and Possible Action on an Appeal of a Decision by the Historic 15‐57 Preservation Commission to Deny an Application by Carle and Robert Egger, 309 Franklin Street, to Paint their House 19C‐0390. Second Reading and Possible Approval of an Ordinance to Rezone 624 Spring 58 Street from Low Density Residential District to Neighborhood Commercial District 19C‐0392. Second Reading and Possible Approval of an Ordinance Amending Article 0, 59‐78 Section §154.015 – Definitions and Article 4, Table 154.403.1 – Permitted Land Uses and Section §154.406 – Detailed Land Use Descriptions of the Code of Ordinances (Adult‐Use Recreational Cannabis Zoning Ordinance) NEW BUSINESS ITEM DESCRIPTION PAGE 19C‐0410. -

2019 Most Endangered Historic Places in Illinois

2019 MOST ENDANGERED HISTORIC PLACES IN ILLINOIS 1 12 4 9 5 6 2 8 1 Greek Housing at James R. Thompson Center 3 Chicago, Cook County University of Illinois Urbana, Champaign County 10 2 11 Sheffield National Register Ray House Historic District Rushville, Schuyler County Chicago, Cook County 11 12 3 10 Washington Park National Bank Rock Island County Chicago, Cook County Courthouse Rock Island, Rock Island County 9 4 7 St. Mary’s School Chancery & Piety Hill Galena, Jo Daviess County Properties Rockford, Winnebago County 5 8 6 7 Booth Cottage Hill Motor Sales Building Glencoe, Cook County Oak Park, Cook County Hoover Estate Millstadt Milling & Feed Company Glencoe, Cook County Millstadt, St. Clair County LANDMARKS ILLINOIS 2019 Most Endangered Historic Places in Illinois JAMES R. THOMPSON CENTER MILLSTADT MILLING & FEED COMPANY 100 W Randolph Street, Chicago, Cook County 419 S Jefferson Street, Millstadt, St. Clair County For the third year in a row, LI is including the one-of-a-kind, state-owned Built in 1857 with a grain elevator added in 1880, the property is one of building in Chicago’s Loop on its Most Endangered list. Designed by the oldest continually operating grain elevators in the state and Helmut Jahn in 1985, the Thompson Center remains threatened as the represents a critical piece of Illinois’ industrial and agricultural past. State of Illinois continues to pursue a sale of the building that could allow Despite its historic significance and sound condition, Millstadt village new development on the site. In March 2019, Gov. JB Pritzker signed officials have declared the site a “public nuisance” and given the current legislation that outlines a two-year plan for the building’s sale. -

Vii. Appendices

VII. APPENDICES PRELIMINARY CULTURAL LANDSCAPE ASSESSMENT OF KENT COUNTY, MARYLAND Figure 7-1: Jesse Spencer House, or Chesterville Brick House, shortly after being saved and moved for restoration, ca. 1978 photo A. LIST OF NATIONAL REGISTER, EASEMENT, AND MIHP PROPERTIES Preliminary Cultural Landscape Assessment of Kent County, MD MIHP National # NationalRegisterSiteinKentCounty,MD Address County Town No. RegisterRef MiddleHallWashingtonCollege(Middle 1 K1 79001138 WashingtonAvenue Kent Chestertown College) 2 K2 EastHallWashingtonCollege(EastCollege) 79001138 WashingtonAvenue Kent Chestertown 3 K3 WestHallWashingtonCollege(WestCollege) 79001138 WashingtonAvenue Kent Chestertown 4 K10 Widehall(WaterLot#16) 72000584 101N.WaterStreet Kent Chestertown RiverHouse(SmythLetherburyHouse,Denton 5 K12 71000377 107N.WaterStreet Kent Chestertown WeeksHouse) 6 K79 Lauretum(VickersHouse) 97000926 954HighStreet(MD20) Kent Chestertown 7 K88 GodlingtonManor 72000583 7201WilkinsLane(MD664) Kent Chestertown 8 K90 TheReward(Tilden'sFarm) 76001004 WalnutPointRoad Kent Johnsontown 9 K92 Clark'sConveniency 75000906 QuakerNeckRoad(MD289) Kent Johnsontown 10 K94 AiryHill 96001478 7909AiryHillRoad Kent Chestertown Hinchingham(HinchinghamontheBay,Bay 11 K101 75000907 20874HinchinghamLane Kent RockHall ShoreFarm,WilmerFarm,GaleFarm) 12 K105 FairleeManorCamp(FareLee,HandyFarm) 73000931 22242BayShoreRoad Kent Georgetown Shepherd'sDelight(Houseonpartof 13 K111 76001007 11818StillPondRoad(MD292) Kent Hepbron Camelsworthmore) 14 K112 Hebron 78001471 12591StillPondRoad(MD292) -

Illinois July 2010 NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC

SEC II – IL Tech Guide Cultural Resources - 1 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES IN ILLINOIS Adams County Camp Point F. D. Thomas House, 321 N. Ohio St. (7-28-83) Clayton vicinity Lewis Round Barn, northwest of Clayton (8-16-84) John Roy Site, south of Clayton (5-22-78) Golden Exchange Bank, Quincy St. (2-12-87) Golden vicinity Ebenezer Methodist Episcopal Chapel and Cemetery, northwest of Golden (6-4-84) Mendon vicinity Lewis Round Barn, 2007 E. 1250th St. (1-29-03) Payson vicinity Fall Creek Stone Arch Bridge, 1.2 mi. northeast of Fall Creek-Payson Rd. (11-7-96) Quincy Coca-Cola Bottling Company Building, 616 N. 24th St. (2-7-97) Downtown Quincy Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire, Jersey, Fourth, and Eighth Sts. (4-7-83) Robert W. Gardner House, 613 Broadway St. (6-20-79) S. J. Lesem Building, 135-37 N. Third St. (11-22-99) Lock and Dam No. 21 Historic District32, .5 mi W of IL 57 (3-10-04) Morgan-Wells House, 421 Jersey St. (11-16-77) Richard F. Newcomb House, 1601 Maine St. (6-3-82) One-Thirty North Eighth Building, 130 N. Eighth St. (2-9-84) Quincy East End Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire,24th, State, and Twelfth Sts. (11-14-85) Quincy Northwest Historic District, roughly bounded by Broadway and N. Second, Locust, and N. Twelfth Sts. (5-11-00) South Side German Historic District, roughly bounded by Sixth,Twelfth, Washington, Jersey, and York Sts. (5-22-92). Boundary increase, roughly bounded by Jefferson, S. -

Illinois March 2008 NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC PLACES

SEC II – IL Tech Guide Cultural Resources - 1 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES IN ILLINOIS Adams County Camp Point F. D. Thomas House, 321 N. Ohio St. (7-28-83) Clayton vicinity Lewis Round Barn, northwest of Clayton (8-16-84) John Roy Site, south of Clayton (5-22-78) Golden Exchange Bank, Quincy St. (2-12-87) Golden vicinity Ebenezer Methodist Episcopal Chapel and Cemetery, northwest of Golden (6-4-84) Mendon vicinity Lewis Round Barn, 2007 E. 1250th St. (1-29-03) Payson vicinity Fall Creek Stone Arch Bridge, 1.2 mi. northeast of Fall Creek-Payson Rd. (11-7-96) Quincy Coca-Cola Bottling Company Building, 616 N. 24th St. (2-7-97) Downtown Quincy Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire, Jersey, Fourth, and Eighth Sts. (4-7-83) Robert W. Gardner House, 613 Broadway St. (6-20-79) S. J. Lesem Building, 135-37 N. Third St. (11-22-99) Lock and Dam No. 21 Historic District32, .5 mi W of IL 57 (3-10-04) Morgan-Wells House, 421 Jersey St. (11-16-77) Richard F. Newcomb House, 1601 Maine St. (6-3-82) One-Thirty North Eighth Building, 130 N. Eighth St. (2-9-84) Quincy East End Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire,24th, State, and Twelfth Sts. (11-14-85) Quincy Northwest Historic District, roughly bounded by Broadway and N. Second, Locust, and N. Twelfth Sts. (5-11-00) South Side German Historic District, roughly bounded by Sixth,Twelfth, Washington, Jersey, and York Sts. (5-22-92). Boundary increase, roughly bounded by Jefferson, S.