Digital Scenography in Opera in the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soprano NICOLETA ARDELEAN Universitary Associate Professor At

Soprano NICOLETA ARDELEAN Universitary Associate Professor at the Faculty of Arts from the Ovidius University of Constanța, professor doctor in music Nicoleta Ardelean graduated, with bachelor’s degree, the specializations Musical Pedagogy-Religious music and Canto-Canto professor, masteral and doctoral studies , all of these at the Music Academy G.Dima from Cluj-Napoca. She has been awarded the Great Prize at the National Vocal Interpretation Contest Sabin Drăgoi at Timişoara in 1999 and the Third Prize at the International Canto Contest Hariclea Darclee at Brăila in 1999. In 2000 she was awarded the N. Bretan Prize at the International Vocal Interpretation Contest Nicolae Bretan at Cluj Napoca and at the International Contest of Canto from Bilbao, Spain, Second Prize and the Music Critics Prize . In 2001, after her international debut on the stage of the Strasbourg Opera, she was awarded the Prize of recognition of artistic talent, by the European Culture Foundation from the European Parliament. After her international debut at Strasbourg in 2001, with Micaela from Bizet’s “Carmen”, she was hired to sing the part of Antonia from “Hoffmann’s Stories” by Jacques Offenbach and that of Ines from „L’Africaine” by Giacomo Meyerbeer. The Opera from Marseille, France, invited her for Mimi in “La Boheme” and for Liu in “Turandot”, and the Theatre from Toulouse for Nedda in „Pagliacci” by Leoncavallo. In 2001, Nicoleta Ardelean performs for the first time in Germany, in the New Year’s Concert with the Berlin Symphonic Orchestra, followed by the roles of Micaela and Antonia at the Opera in Leipzig. -

THE 42Nd COMPARATIVE DRAMA CONFERENCE the Comparative Drama Conference Is an International, Interdisciplinary Event Devoted to All Aspects of Theatre Scholarship

THE 42nd COMPARATIVE DRAMA CONFERENCE The Comparative Drama Conference is an international, interdisciplinary event devoted to all aspects of theatre scholarship. It welcomes papers presenting original investigation on, or critical analysis of, research and developments in the fields of drama, theatre, and performance. Papers may be comparative across disciplines, periods, or nationalities, may deal with any issue in dramatic theory and criticism, or any method of historiography, translation, or production. Every year over 170 scholars from both the Humanities and the Arts are invited to present and discuss their work. Conference participants have come from over 35 countries and all fifty states. A keynote speaker whose recent work is relevant to the conference is also invited to address the participants in a plenary session. The Comparative Drama Conference was founded by Dr. Karelisa Hartigan at the University of Florida in 1977. From 2000 to 2004 the conference was held at The Ohio State University. In 2005 the conference was held at California State University, Northridge. From 2006 to 2011 the conference was held at Loyola Marymount University. Stevenson University was the conference’s host from 2012 through 2016. Rollins College has hosted the conference since 2017. The Conference Board Jose Badenes (Loyola Marymount University), William C. Boles (Rollins College), Miriam M. Chirico (Eastern Connecticut State University), Stratos E. Constantinidis (The Ohio State University), Ellen Dolgin (Dominican College of Blauvelt), Verna Foster (Loyola University, Chicago), Yoshiko Fukushima (University of Hawai'i at Hilo), Kiki Gounaridou (Smith College), Jan Lüder Hagens (Yale University), Karelisa Hartigan (University of Florida), Graley Herren (Xavier University), William Hutchings (University of Alabama at Birmingham), Baron Kelly (University of Louisville), Jeffrey Loomis (Northwest Missouri State University), Andrew Ian MacDonald (Dickinson College), Jay Malarcher (West Virginia University), Amy Muse (University of St. -

June 17 – Jan 18 How to Book the Plays

June 17 – Jan 18 How to book The plays Online Select your own seat online nationaltheatre.org.uk By phone 020 7452 3000 Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 8pm In person South Bank, London, SE1 9PX Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 11pm Other ways Friday Rush to get tickets £20 tickets are released online every Friday at 1pm Saint George and Network Pinocchio for the following week’s performances. the Dragon 4 Nov – 24 Mar 1 Dec – 7 Apr Day Tickets 4 Oct – 2 Dec £18 / £15 tickets available in person on the day of the performance. No booking fee online or in person. A £2.50 fee per transaction for phone bookings. If you choose to have your tickets sent by post, a £1 fee applies per transaction. Postage costs may vary for group and overseas bookings. Access symbols used in this brochure CAP Captioned AD Audio-Described TT Touch Tour Relaxed Performance Beginning Follies Jane Eyre 5 Oct – 14 Nov 22 Aug – 3 Jan 26 Sep – 21 Oct TRAVELEX £15 TICKETS The National Theatre Partner for Innovation Partner for Learning Sponsored by in partnership with Partner for Connectivity Outdoor Media Partner Official Airline Official Hotel Partner Oslo Common The Majority 5 – 23 Sep 30 May – 5 Aug 11 – 28 Aug Workshops Partner The National Theatre’s Supporter for new writing Pouring Partner International Hotel Partner Image Partner for Lighting and Energy Sponsor of NT Live in the UK TBC Angels in America Mosquitoes Amadeus Playing until 19 Aug 18 July – 28 Sep Playing from 11 Jan 2 3 OCTOBER Wed 4 7.30 Thu 5 7.30 Fri 6 7.30 A folk tale for an Sat 7 7.30 Saint George and Mon 9 7.30 uneasy nation. -

Curriculum-Nicola-Pamio.Pdf

NICOLA PAMIO TENORE 0039 338312157 [email protected] Apprezzato per le sue doti sceniche è di particolare interesse la sua collaborazione con il Teatro alla Scala, iniziata nel 1999. Nel teatro milanese è stato impegnato neI Matrimonio di Musorgskij, in Manon di Massenet con la direzione di Gary Bertini e la regia di Nicolas Joel, in Peter Grimes,nel ruolo di Rev.Horace con la direzione di Jeffrey Tate e la regia di John Schlesinger, in Tatjana di Azio Corghi con la regia di Peter Stein e la direzione di Will Humburg e in Pagliacci diretto da Daniel Harding con la regia di Mario Martone. Ha interpretato Il Barbiere di Siviglia con la regia di Carlo Verdone al Teatro dell’Opera di Roma. Alle spalle ha circa trenta produzioni Scaligere , tra le più recenti Otello di Rossini, Rigoletto , Fedora, Traviata, Adriana Lecouvreur, Nozze di Figaro , Andrea Chénier, Tatiana di Azio Corghi, Volpe Astuta , Gli Stivaletti , Boris G. , lavorando con i massimi esponenti della musica Lirica Internazionale come il Maestro Muti , Valerie Gergiev, J. Tate, J. Conlon, Sir. Andrew Davis, Dudamel, Harding, Gatti, Rustioni, Renzetti, e Registi del calibro di Zeffirelli, Puggelli, Ronconi , Stein, Pizzi, Michieletto, Moshe Leiser. Nel 2011 è stato invitato a New York alla Carnagie Hall per Adriana lecouvreur (Abate) con J. Kaufman, A. Gheorghiu , e nel 2013 all’ Avery Fisher Hall nell’opera Andrea Chénier (Incredibile), con Roberto Alagna , riscuotendo grande interesse dalla critica del New York Times . Da due anni lavora con Cecilia Bartoli prima a Zurigo poi a Parigi e al Festival di Salisburgo nell’Otello di Rossini, effettuando la registrazione per la Decca. -

Thursday 17 January 2019 National Theatre: February

Thursday 17 January 2019 National Theatre: February – July 2019 Inua Ellams’ Barber Shop Chronicles will play at the Roundhouse, Camden for a limited run from July as part of a UK tour Gershwyn Eustache Jnr, Leah Harvey and Aisling Loftus lead the cast of Small Island, adapted by Helen Edmundson from Andrea Levy’s prize-winning novel, directed by Rufus Norris in the Olivier Theatre Justine Mitchell joins Roger Allam in Rutherford and Son by Githa Sowerby, directed by Polly Findlay Phoebe Fox takes the title role of ANNA in Ella Hickson and Ben and Max Ringham’s tense thriller directed by Natalie Abrahami Further casting released for Peter Gynt, directed by Jonathan Kent, written by David Hare, after Henrik Ibsen War Horse will return to London as part of the 2019 UK and international tour, playing at a new venue, Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre, for a limited run in October Olivier Theatre SMALL ISLAND adapted by Helen Edmundson based on the novel by Andrea Levy Previews from 17 April, press night 1 May, in repertoire until 10 August Andrea Levy’s epic, Orange Prize-winning novel bursts into new life on the Olivier Stage. A cast of 40 tell a story which journeys from Jamaica to Britain through the Second World War to 1948, the year the HMT Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury. Adapted for the stage by Helen Edmundson Small Island follows the intricately connected stories of two couples. Hortense yearns for a new life away from rural Jamaica, Gilbert dreams of becoming a lawyer, and Queenie longs to escape her Lincolnshire roots. -

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time Embarks on a Third Uk and Ireland Tour This Autumn

3 March 2020 THE NATIONAL THEATRE’S INTERNATIONALLY-ACCLAIMED PRODUCTION OF THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME EMBARKS ON A THIRD UK AND IRELAND TOUR THIS AUTUMN • TOUR INCLUDES A LIMITED SEVEN WEEK RUN AT THE TROUBADOUR WEMBLEY PARK THEATRE FROM WEDNESDAY 18 NOVEMBER 2020 Back by popular demand, the Olivier and Tony Award®-winning production of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time will tour the UK and Ireland this Autumn. Launching at The Lowry, Salford, Curious Incident will then go on to visit to Sunderland, Bristol, Birmingham, Plymouth, Southampton, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Dublin, Belfast, Nottingham and Oxford, with further venues to be announced. Curious Incident will also play for a limited run in London at Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre in Brent - London Borough of Culture 2020 - following the acclaimed run of War Horse in 2019. Curious Incident has been seen by more than five million people worldwide, including two UK tours, two West End runs, a Broadway transfer, tours to the Netherlands, Canada, Hong Kong, Singapore, China, Australia and 30 cities across the USA. Curious Incident is the winner of seven Olivier Awards including Best New Play, Best Director, Best Design, Best Lighting Design and Best Sound Design. Following its New York premiere in September 2014, it became the longest-running play on Broadway in over a decade, winning five Tony Awards® including Best Play, six Drama Desk Awards including Outstanding Play, five Outer Critics Circle Awards including Outstanding New Broadway Play and the Drama League Award for Outstanding Production of a Broadway or Off Broadway Play. -

Read the 2015/2016 Financial Statement

ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 National Theatre Page 1 of 87 PUBLIC BENEFIT STATEMENT In developing the objectives for the year, and in planning activities, the Trustees have considered the Charity Commission’s guidance on public benefit and fee charging. The repertoire is planned so that across a full year it will cover the widest range of world class theatre that entertains, inspires and challenges the broadest possible audience. Particular regard is given to ticket-pricing, affordability, access and audience development, both through the Travelex season and more generally in the provision of lower price tickets for all performances. Geographical reach is achieved through touring and NT Live broadcasts to cinemas in the UK and overseas. The NT’s Learning programme seeks to introduce children and young people to theatre and offers participation opportunities both on-site and across the country. Through a programme of talks, exhibitions, publishing and digital content the NT inspires and challenges audiences of all ages. The Annual Report is available to download at www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/annualreport If you would like to receive it in large print, or you are visually impaired and would like a member of staff to talk through the publication with you, please contact the Board Secretary at the National Theatre. Registered Office & Principal Place of Business: The Royal National Theatre, Upper Ground, London. SE1 9PX +44 (0)20 7452 3333 Company registration number 749504. Registered charity number 224223. Registered in England. Page 2 of 87 CONTENTS Public Benefit Statement 2 Current Board Members 4 Structure, Governance and Management 5 Strategic Report 8 Trustees and Directors Report 36 Independent Auditors’ Report 45 Financial Statements 48 Notes to the Financial Statements 52 Reference and Administrative Details of the Charity, Trustees and Advisors 86 In this document The Royal National Theatre is referred to as “the NT”, “the National”, and “the National Theatre”. -

Dossier De Presse

dessin William Kentridge — graphisme Jérôme Le Scanff Jérôme Le — graphisme Kentridge William dessin DOSSIER DE PRESSE sommaire 5 Entretien avec Hortense Archambault 76 kornél mundruczó et Vincent Baudriller up DISGRÂCE DE J. M. COETZEE 8 c / COMPLICITE artiste associé simon m burney 79 steven cohen u LE MAÎTRE ET MARGUERITE DE MIKHAÏL BOULGAKOV c p SANS TITRE. POUR RAISONS LÉGALES ET ÉTHIQUES 13 john berger c p LE BERCEAU DE L’HUMANITÉ u DE A À X 83 romeo castellucci / SOCÌETAS RAFFAELLO SANZIO u EST-CE QUE TU DORS ? u THE FOUR SEASONS RESTAURANT 16 sophie calle 86 markus öhrn / institutet / nya rampen È RACHEL, MONIQUE up CONTE D’AMOUR 19 arthur nauzyciel 89 jérôme bel / theater hora u2 LA MOUETTE D’ANTON TCHEKHOV uc DISABLED THEATER 23 / LA COLLINE - THÉÂTRE NATIONAL stéphane braunschweig 92 sandrine buring & stéphane olry / LA REVUE ÉCLAIR u SIX PERSONNAGES EN QUÊTE D’AUTEUR cu2 CH(OSE) / HIC SUNT LEONES D’APRÈS LUIGI PIRANDELLO 96 christian rizzo.. / L’ASSOCIATION.. FRAGILE 26 forced entertainment c SAKINAN GOZE ÇOP BATAR u LES FÊTES DE DEMAIN 98 / EASTMAN u L’ORAGE À VENIR sidi larbi cherkaoui .. c2 PUZ/ZLE 30 katie mitchell / SCHAUSPIEL KOLN 101 u LES ANNEAUX DE SATURNE D’APRÈS LE ROMAN DE W. G. SEBALD olivier dubois c TRAGÉDIE 32 katie mitchell & stephen emmott DIX MILLIARDS 104 josef nadj .. c ATEM LE SOUFFLE 34 thomas ostermeier / SCHAUBUHNE BERLIN 107 u UN ENNEMI DU PEUPLE D’HENRIK IBSEN nacera belaza c LE TRAIT 37 william kentridge 109 régine chopinot / CORNUCOPIAE & le wetr u2cp LA NÉGATION DU TEMPS c2 VERY WETR ! ÈDA CAPO 112 romeu runa & miguel moreira / LES BALLETS C DE LA B 40 suzanne andrade & paul barritt / 1927 c THE OLD KING u2p LES ANIMAUX ET LES ENFANTS ENVAHIRENT LA RUE 115 komplexkapharnaüm 43 christoph marthaler / THEATER BASEL up2 PLACE PUBLIC u2 MY FAIR LADY. -

2019 EVITA Lloyd Webber & Rice the Marriage of Figaro Mozart the Manchurian Candidate Puts & Campbell Oklahoma! Rodgers & Hammerstein

seagle music colony 2019 EVITA Lloyd Webber & Rice The Marriage of Figaro Mozart The Manchurian Candidate Puts & Campbell Oklahoma! Rodgers & Hammerstein Vespers Monkey & Francine Concerts in the City of Tigers * seaglecolony.org Bringing Music to the Adirondacks Since 1915 The Beechwood Group of Wells Fargo Advisors is proud to support The Seagle Music Colony Joseph Steiniger Senior Vice President - Investment Officer CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ [email protected] Mary E. McDonald First Vice President - Investments [email protected] The Beechwood Group 845-483-7943 www.thebeechwoodgroup.com Investment and Insurance Products: NOT FDIC Insured NO Bank Guarantee MAY Lose Value Wells Fargo Advisors, LLC, Member SIPC, is a registered broker-dealer and a separate non-bank affiliate of Wells Fargo & Company. ©2013 Wells Fargo Advisors, LLC. All rights reserved. 1113-02329 [74127-v4] Table of Contents General Information About Seagle Music Colony Restrooms are located in the Shames Rehearsal Notes from the Directors 3 Studio. Handicapped accessible restroom Seagle Music Colony Board of Directors 4 is at the rear of the theatre lobby. Seagle Music Colony Guild 4 History of Seagle Music Colony 7 Refreshments are provided in the theatre lobby 2018-2019 Seagle Music Colony Donors 8 by the Seagle Music Colony Guild. Donor Opportunities 12 2018-19 Alumni Updates 35 So that all our patrons may enjoy the performance, please turn all cell phones and pagers The Seagle Music Colony Gala 17 to the silent or off positions. The Productions Thank you for attending today’s performance. Evita 14 Monkey & Francine in the City of Tigers 16 The Marriage of Figaro 18 The Manchurian Candidate 22 Seagle Music Colony Oklahoma! 24 999 Charley Hill Road 2019 Fall Season 26 PO Box 366 Schroon Lake, NY 12870 2019 Faculty/Staff & Emerging Artists (518) 532-7875 Faculty & Staff 27 Emerging Artists 33 seaglecolony.org [email protected] Our Mission To identify, train and develop gifted singers and to present quality opera and musical theatre performances to the public. -

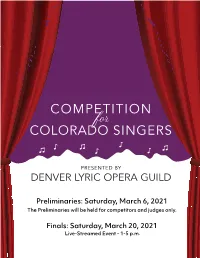

2021 Competition Program

Preliminaries: Saturday, March 6, 2021 The Preliminaries will be held for competitors and judges only. Finals: Saturday, March 20, 2021 Live-Streamed Event - 1-5 p.m. The objective of the Denver Lyric Opera Guild is the encouragement and support of young singers and the continuing education of members in the appreciation and knowledge of opera. For more information on DLOG Membership and Member Events www.denverlyricoperaguild.org Denver Lyric Opera Guild Denver Lyric Opera Guild is a non-profit membership organization of over 180 members. DLOG was founded in 1965 to help support the Denver Lyric Opera Company. The opera company was forced to close in 1968, but the Guild pursued other programs in keeping with its purpose to encourage and support young singers and provide continuing education to the members in the appreciation and knowledge of opera. Competition for Colorado Singers In 1984, the Guild inaugurated its signature event, the Competition for Colorado Singers, to support singers ages 23-32 in pursuing their operatic careers. Since then, the Guild has awarded over $850,000 to Competition winners. Hundreds of young singers have successfully launched their operatic and musical careers since winning the Competition. Grants The Guild provides grants to Colorado’s colleges and universities for vocal scholarships, and to apprentice opera programs. Over the years, these grants have totaled over $812,000 from the earnings on our endowment. Grants are given to the voice performance programs at Colorado State University, Metro State University of Denver, University of Colorado, University of Denver, University of Northern Colorado, and young artist apprentice programs of Central City Opera, Opera Colorado, Opera Fort Collins, and Opera Theatre of the Rockies in Colorado Springs. -

Preliminaries: Saturday, March 6, 2021 Finals

Preliminaries: Saturday, March 6, 2021 The Preliminaries will be held for competitors and judges only. Finals: Saturday, March 20, 2021 Live-Streamed Event - 1-5 p.m. The objective of the Denver Lyric Opera Guild is the encouragement and support of young singers and the continuing education of members in the appreciation and knowledge of opera. For more information on DLOG Membership and Member Events www.denverlyricoperaguild.org Denver Lyric Opera Guild Denver Lyric Opera Guild is a non-profit membership organization of over 180 members. DLOG was founded in 1965 to help support the Denver Lyric Opera Company. The opera company was forced to close in 1968, but the Guild pursued other programs in keeping with its purpose to encourage and support young singers and provide continuing education to the members in the appreciation and knowledge of opera. Competition for Colorado Singers In 1984, the Guild inaugurated its signature event, the Competition for Colorado Singers, to support singers ages 23-32 in pursuing their operatic careers. Since then, the Guild has awarded over $850,000 to Competition winners. Hundreds of young singers have successfully launched their operatic and musical careers since winning the Competition. Grants The Guild provides grants to Colorado’s colleges and universities for vocal scholarships, and to apprentice opera programs. Over the years, these grants have totaled over $812,000 from the earnings on our endowment. Grants are given to the voice performance programs at Colorado State University, Metro State University of Denver, University of Colorado, University of Denver, University of Northern Colorado, and young artist apprentice programs of Central City Opera, Opera Colorado, Opera Fort Collins, and Opera Theatre of the Rockies in Colorado Springs. -

FY19 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2018–19 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 6 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 20 Our Patrons On the cover: Yannick Nézet-Séguin takes a bow after his first official performance as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director PHOTO: JONATHAN TICHLER / MET OPERA 2 Introduction The 2018–19 season was a historic one for the Metropolitan Opera. Not only did the company present more than 200 exiting performances, but we also welcomed Yannick Nézet-Séguin as the Met’s new Jeanette Lerman- Neubauer Music Director. Maestro Nézet-Séguin is only the third conductor to hold the title of Music Director since the company’s founding in 1883. I am also happy to report that the 2018–19 season marked the fifth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so, as we recorded a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Saint-Saëns’s epic Samson et Dalila and also included three other new productions, as well as three exhilarating full cycles of Wagner’s Ring and a full slate of 18 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 13th season, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office, media, and presentations) totaled $121 million. As in past seasons, total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. The new productions in the 2018–19 season were the work of three distinguished directors, two having had previous successes at the Met and one making his company debut.