The Migration of Mary Haggerty Ferry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Proposed Dredging of the Navigation Channel at Sligo Harbour Vol

The Proposed Dredging of the Navigation Channel at Sligo Harbour Vol. 3: Natura Impact Statement, to inform Appropriate Assessment rpsgroup.com Sligo Harbour Dredging Natura Impact Statement An ecological impact assessment to support the Appropriate Assessment Process Produced by Aqua-Fact International Services Ltd On behalf of RPS Limited Issued October 2012 AQUA-FACT INTERNATIONAL SERVICES ltd 12 KILKERRIN park TUAM rd GALWAY city www.aquafact.ie [email protected] tel +353 (0) 91 756812 fax +353 (0) 91 756888 Sligo Harbour Dredging RPS Ireland Ltd Natura Impact Statement October 2012 ii /JN1075 Sligo Harbour Dredging RPS Ireland Ltd Natura Impact Statement October 2012 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 1.1. The requirement for an assessment under Article 6 ............................... 1 1.2. The aim of this report .............................................................................. 2 1.3. Background – an overview of the Sligo Harbour Dredging project.......... 2 1.4. Consultation ............................................................................................ 3 1.4.1. Government Departments ............................................................................. 3 1.4.2. Other Bodies ................................................................................................. 3 1.5. Constraints.............................................................................................. 4 2. The Appropriate -

The Freedom of a Road Trip the Wild Atlantic Way in Ireland Is One of the Most Scenic Coastal Roads in the World

newsroom Scene and Passion Jul 18, 2019 The freedom of a road trip The Wild Atlantic Way in Ireland is one of the most scenic coastal roads in the world. German travel blogger Sebastian Canaves from “Off the Path” visited this magical place with the Porsche 718 Cayman GTS. “Road trips are the ultimate form of travel — complete freedom,” says Sebastian Canaves. His eyes sweep over the almost endless rich green of Ireland, the steep cliffs and finally out to the open sea. A stiff breeze blows into the face of the travel blogger, who is exploring the Wild Atlantic Way in Ireland together with his partner Line Dubois and the Porsche 718 Cayman GTS. Sebastian Canaves has travelled the world. He has already seen all the continents of this earth, visited more than 100 countries, and runs one of the most successful travel blogs in Europe with “Off the Path”. And yet, at this moment, you can feel how impressed he is by the natural force of Ireland and the ever-present expanse of the country. “This is one of the most spectacular and beautiful road trips I know,” says the outdoor expert. He is referring to the Wild Atlantic Way. More than 2,600 km in length, this is one of the longest and oldest defined coastal roads in the world. From the far north and the sleepy villages of Donegal to the small coastal town of Kinsale in the south of County Cork, the road hugs the coast directly next to the ocean. “A new adventure awaits around every corner,” says Canaves. -

Donegal Bay North Catchment Assessment 2010-2015 (HA 37)

Donegal Bay North Catchment Assessment 2010-2015 (HA 37) Catchment Science & Management Unit Environmental Protection Agency September 2018 Version no. 3 Preface This document provides a summary of the characterisation outcomes for the water resources of the Donegal Bay North Catchment, which have been compiled and assessed by the EPA, with the assistance of local authorities and RPS consultants. The information presented includes status and risk categories of all water bodies, details on protected areas, significant issues, significant pressures, load reduction assessments, recommendations on future investigative assessments, areas for actions and environmental objectives. The characterisation assessments are based on information available to the end of 2015. Additional, more detailed characterisation information is available to public bodies on the EPA WFD Application via the EDEN portal, and more widely on the catchments.ie website. The purpose of this document is to provide an overview of the situation in the catchment and help inform further action and analysis of appropriate measures and management strategies. This document is supported by, and can be read in conjunction with, a series of other documents which provide explanations of the elements it contains: 1. An explanatory document setting out the full characterisation process, including water body, subcatchment and catchment characterisation. 2. The Final River Basin Management Plan, which can be accessed on: www.catchments.ie. 3. A published paper on Source Load Apportionment Modelling, which can be accessed at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3318/bioe.2016.22 4. A published paper on the role of pathways in transferring nutrients to streams and the relevance to water quality management strategies, which can be accessed at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.3318/bioe.2016.19.pdf 5. -

Sliabh Liag Peninsula / Slí Cholmcille

SLIABH LIAG PENINSULA / SLÍ CHOLMCILLE www.hikingeurope.net THE ROUTE: ABOUT: A scenic coastal hike along the Wild Atlantic Way taking in local culture and This tour is based around the spectacular coast between the towns of history Killybegs and Ardara in County Donegal. The area is home to Sliabh Liag HIGHLIGHT OF THE ROUTE: (Slieve League) one of the highest sea cliffs in Europe and also a key signature discovery point along the Wild Atlantic Way. The breathtaking Experience the spectacular views from one of Europe’s highest sea cliffs at views at Sliabh Liag rightly draw visitors from all four corners of the globe. Sliabh Liag Unlike most, who fail to stray far from the roads, you get the chance to see SCHEMATIC TRAIL MAP: the cliffs in all their glory. The walk follows the cliffs from the viewing point at Bunglass to the ruins of the early-Christian monastery of Saint Aodh McBricne. The views from around the monastery are simply jaw dropping, with the great sweep of land to the east and the ocean far below to the west. The tour follows much of “Slí Cholmcille” part of the Bealach Na Gaeltachta routes and takes in the village of Glencolmcille where wonderful coastal views across the bay to Glen head await and a number of pre and early- Christine sites in the valley can be visited. The route concludes in Ardara, a centre renowned for traditional Irish music and dance, local festivals and numerous bars and restaurants. NAME OF THE ROUTE: Sliabh Liag / Sli Cholmcille leaving the road to cross a low hill to take you to your overnight destination overlooking Donegal Bay. -

Rossnowlagh (2016)

Bathing Water Profile - Rossnowlagh (2016) Bathing Water: Rossnowlagh Bathing Water Code: IENWBWC010_0000_0200 Local Authority: Donegal County Council River Basin District: North Western Monitoring Point: 186120E, 367273N 1. Profile Details: Profile Id: BWPR00340 Toilets Available: Yes Year Of Profile: 2016 Car Parking Available: Yes Year Of Identification 1992 Disabled Access: Yes Version Number: 1 First Aid Available: Yes Sensitive Area: Yes Dogs Allowed: Yes Lifesaving Facilities: No Figure 1: Bathing Water 2. Bathing Water Details: Map 1: Bathing Water Location & Extent Bathing Water location and Rossnowlagh (Ros Neamhlach) Beach is located on the South Coast of Donegal, approximately 6 km from extent: Ballintra and Ballyshannon. The beach is situated in a rural area and not directly beside any towns or villages; but has become built up with an extensive network of houses and caravan parks. It is located in the Donegal Bay (Erne) Coastal waterbody (NW_010_0000) within the North Western River Basin District. The designated bathing area is approx. 0.9054km2 and the extent along the water is approximately is 2150m Main features of the Bathing Type of Bathing Water: Rossnowlagh beach consists of a long sandy beach; confined by the Coolmore Water: cliffs to the South and extends up to Inishfad at Durnesh Lake to the North. The Bay is West facing into the Atlantic Ocean and gets a strong wash of water from the Atlantic onto the beach. Flora/Fauna, Riparian Zone: The beach and catchment makes up only a small area. The riparian zone is semi-natural with reinforced banks at the extensive caravan sites and some scattered on off housing development in the catchment behind the beachfront. -

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

Why Donegal Slept: the Development of Gaelic Games in Donegal, 1884-1934

WHY DONEGAL SLEPT: THE DEVELOPMENT OF GAELIC GAMES IN DONEGAL, 1884-1934 CONOR CURRAN B.ED., M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SPORTS HISTORY AND CULTURE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY LEICESTER SUPERVISORS OF RESEARCH: FIRST SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MATTHEW TAYLOR SECOND SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MIKE CRONIN THIRD SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR RICHARD HOLT APRIL 2012 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations v Abstract vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Donegal and society, 1884-1934 27 Chapter 2 Sport in Donegal in the nineteenth century 58 Chapter 3 The failure of the GAA in Donegal, 1884-1905 104 Chapter 4 The development of the GAA in Donegal, 1905-1934 137 Chapter 5 The conflict between the GAA and association football in Donegal, 1905-1934 195 Chapter 6 The social background of the GAA 269 Conclusion 334 Appendices 352 Bibliography 371 ii Acknowledgements As a rather nervous schoolboy goalkeeper at the Ian Rush International soccer tournament in Wales in 1991, I was particularly aware of the fact that I came from a strong Gaelic football area and that there was only one other player from the south/south-west of the county in the Donegal under fourteen and under sixteen squads. In writing this thesis, I hope that I have, in some way, managed to explain the reasons for this cultural diversity. This thesis would not have been written without the assistance of my two supervisors, Professor Mike Cronin and Professor Matthew Taylor. Professor Cronin’s assistance and knowledge has transformed the way I think about history, society and sport while Professor Taylor’s expertise has also made me look at the writing of sports history and the development of society in a different way. -

Sainte Anne's (F94 A6N4)

Bridge Street Killybegs Co. Donegal Ireland CRO: 289989 PSRA Licence No: 002810 Tel: 074 97 31140 074 97 31291 Fax: 074 97 31988 Email: [email protected] Sainte Anne’s (F94 A6N4) St. John’s Point Asking Price: €345,000 Co. Donegal For Sale by Private Treaty: Sainte Anne’s is a unique coastal property of the highest calibre, which has been finished to an exceptionally high standard and offers beautifully proportioned accommodation over two levels extending to about 231 sq.m (2,330 sq.ft). Sainte Anne’s was originally a stone cottage, which has been significantly extended and upgraded in recent years to create the contemporary house presented today. This strikingly attractive family home has been lovingly designed by the current owners to create a truly beautiful haven orientated around the spectacular views over St. John’s Point Beach. Peached on compact site nestled above the beach the property also enjoys open aspect views into Inver Bay from the west and from the east views into Donegal Bay where you can catch a glimpse of the passing maritime traffic on route to Killybegs Harbour. All in all, Sainte Anne’s is undoubtedly one of Donegal’s finest coastal home’s and offers an extremely rare opportunity to acquire a family home or holiday home with a beach literally on your doorstep. www.dngdorrian.ie AUCTIONEERS ESTATE AGENTS VALUERS LETTING AGENTS MORTGAGES St. John’s Point Beach & Lighthouse: Another Donegal treasure on one of Ireland’s longest peninsulas, majestic St. John’s Point Lighthouse has been a guiding light for Donegal Bay, Killybegs Harbour and Rotten Island since 1833. -

Donegal: COUNTY GEOLOGY of IRELAND 1

Donegal: COUNTY GEOLOGY OF IRELAND 1 DONEGAL AREA OF COUNTY: 4,841 square kilometres or 1,869 square miles COUNTY TOWN: Lifford OTHER TOWNS: Bundoran, Donegal, Letterkenny, Stranorlar GEOLOGY HIGHLIGHTS: Precambrian metamorphic rocks, granites, Lower Carboniferous sandstones and limestones, building materials AGE OF ROCKS: Precambrian; Devonian to Carboniferous Malin Head Precambrian metamorphic schists and quartzite at Malin Head. In the distance is Inishtrahull, composed of the oldest rocks in Ireland. 2 COUNTY GEOLOGY OF IRELAND: Donegal Geological Map of County Donegal Pale Purple: Precambrian Dalradian rocks; Bright blue: Precambrian Gneiss and Schists; Pale yellow: Precambrian Quartzite; Red: Granite; Beige:Beige:Beige: Devonian sandstones; Dark blue: Lower Carboniferous sandstones; Light blue: Lower Carboniferous limestone. Geological history The geology of Co. Donegal most closely resembles that of Co. Mayo, and the county contains the oldest rocks in Ireland, around 1780 million years old, exposed on the offshore island of Inishtrahull. 1000 million years ago [Ma] sediments were deposited in an ocean and an Ice Age that affected the Earth at this time produced glacial till of cobbles of rock set in a matrix of crushed rock. Between 470 and 395 Ma the whole area was subjected to a mountain- building event called the Caledonian Orogeny and the rocks were metamorphosed or altered into gneiss, schists and quartzites now known as the Dalradian Group. Errigal Mountain is composed of this quartzite which weathers to a 'sugarloaf' shape. The metamorphosed glacial deposits are called Tillites. In the late phase of the orogeny two continents collided and the north-east to south-west trend of the rocks in Donegal was produced. -

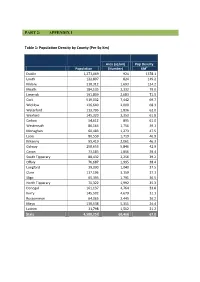

APPENDIX I Table 1: Population Density by County (Per Sq

PART 2: APPENDIX I Table 1: Population Density by County (Per Sq Km) Area (sq km) Pop Density Population (Number) KM2 Dublin 1,273,069 924 1378.1 Louth 122,897 824 149.2 Kildare 210,312 1,693 124.2 Meath 184,135 2,332 79.0 Limerick 191,809 2,683 71.5 Cork 519,032 7,442 69.7 Wicklow 136,640 2,000 68.3 Waterford 113,795 1,836 62.0 Wexford 145,320 2,353 61.8 Carlow 54,612 895 61.0 Westmeath 86,164 1,756 49.1 Monaghan 60,483 1,273 47.5 Laois 80,559 1,719 46.9 Kilkenny 95,419 2,061 46.3 Galway 250,653 5,846 42.9 Cavan 73,183 1,856 39.4 South Tipperary 88,432 2,256 39.2 Offaly 76,687 1,995 38.4 Longford 39,000 1,040 37.5 Clare 117,196 3,159 37.1 Sligo 65,393 1,791 36.5 North Tipperary 70,322 1,992 35.3 Donegal 161,137 4,764 33.8 Kerry 145,502 4,679 31.1 Roscommon 64,065 2,445 26.2 Mayo 130,638 5,351 24.4 Leitrim 31,798 1,502 21.2 State 4,588,252 68,466 67.0 Table 2: Private households in permanent housing units in each Local Authority area, classified by motor car availability. Four or At least One Two Three more one No % of motor motor motor motor motor motor HHlds All hhlds car cars cars cars car car No Car Dublin City 207,847 85,069 36,255 5,781 1,442 128,547 79,300 38.2% Limerick City 22,300 9,806 4,445 701 166 15,118 7,182 32.2% Cork City 47,110 19,391 10,085 2,095 580 32,151 14,959 31.8% Waterford City 18,199 8,352 4,394 640 167 13,553 4,646 25.5% Galway City 27,697 12,262 7,233 1,295 337 21,127 6,570 23.7% Louth 43,897 18,314 13,875 2,331 752 35,272 8,625 19.6% Longford 14,410 6,288 4,548 789 261 11,886 2,524 17.5% Sligo 24,428 9,760 -

North West Pocket Guide

North West Pocket Guide FREE COPY THINGS TO DO PLACES TO SEE FAMILY FUN EVENTS & MAPS AND LOTS MORE... H G F GET IN TOUCH! DONEGAL Donegal Discover Ireland Centre The Quay, Donegal Town, Co. Donegal T 074 9721148 E [email protected] Letterkenny Tourist Office Neil T. Blaney Road, Letterkenny, Co. Donegal T 074 9121160 E [email protected] SLIGO Sligo Tourist Office O’Connell Street, Sligo Town, Co. Sligo T 071 9161201 E [email protected] Visit our website: Follow us on: H G F F CONTENTS Contents Get in Touch Inside Cover Wild Atlantic Way 2 Donegal 10 Leitrim 30 Sligo 44 Adventure & Water Sports 60 Angling 66 Beaches 76 Driving Routes 80 Equestrian 86 Family Fun 90 Food and Culinary 96 Gardens 100 Golf 104 Tracing Ancestry 108 Travel Options 110 Walking & Cycling 114 Festivals & Events 120 Regional Map 144 Family Friendly: This symbol Fáilte Ireland Development Team: denotes attractions that are suitable Editors: Aisling Gillen & Stephen Duffy. for families. Research & Contributors: Amanda Boyle, Aoife McElroy, Claire Harkin, Geraldine Wheelchair Friendly: This symbol McGrath, Lorraine Flaherty, Shona Mehan, denotes attractions that are Patsy Burke wheelchair accessible. Artwork & Production: Photography: TOTEM, The Brewery, Fairlane, Dungarvan, Front Cover: Malin Head, Co Donegal Co Waterford Courtesy of Bren Whelan T: +353 (58) 24832 (www.wildatlanticwayclimbing.com) W: www.totem.ie Internal: Aisling Gillen, Arlene Wilkins, Bren Whelan, Donal Hackett, Publishers: Fáilte Ireland Donegal Golf Club, Donegal Islands, Fáilte 88-95 Amiens Street, Ireland, Inishowen Tourism, Dublin 1. Jason McGarrigle, Pamela Cassidy, T: 1800 24 24 73. Raymond Fogarty, Sligo Fleadh Cheoil, W: www.failteireland.ie Stephen Duffy, Tourism Ireland, Yeats2015 3 Every care has been taken in the compilation of this guidebook to ensure accuracy at the time of publication. -

Donegal West & South. Wild Cats Summer Cruise 2015 Or Close

Donegal West & South. Wild Cats Summer Cruise 2015 Or Close Encounters of the Clutch Kind 20 -26 June 2015 Fahan- Tory Is - Teelin - Killybegs - Portnoo – Burtonport – (Fahan) The 2015 summer cruise was planned as an exploration of my local waters. Despite over 14 years in the northwest of Ireland, I had not ventured much beyond the Northern coast of Donegal. Although the Donegal coast had been calling for some time, other coasts had won over and our own home waters had been somewhat neglected. So 2015 was time to put it right and we would gain Donegal bay. It was also to be a “back to basics” or "Riddle of the Sands" adventure. The mast on my Westerly Falcon, Viking Lord, had been damaged so she was out of commission for 2015. Wild cat is an International H boat which is normally raced on Lough Swilly. Based on the folk boat design & with a 50% ballast ratio she is a capable sea boat but boasts few, if any, home comforts. Still with a couple of snug bunks, a single stove, a selection of buckets and a credible drinks locker what more would one need. Auxiliary power was via a 4HP outboard and is not much use in a sea. Basically we would be sailing wherever we wanted to go. Another novel experience on a cruise ! Wild Cat under the Torrs of Tory Sat 20 June Mid summers day Myself and Eimile, my eldest daughter returned from uni, slipped our lines in Fahan and set off for Tory. Very soon we had a following breeze.