Local Attitudes to Changing Land Use – Narrabri Shire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Region Contract a School Bus Routes

Route Code Route Description N0127 SAN JOSE - BOOMI - EURAL N0128 CLAREMONT - BOOMI N1799 MALLEE - BOGGABRI N0922 'YATTA' - BELLATA N0078 GOORIANAWA TO BARADINE N1924 WARIALDA - NORTH STAR N1797 CRYON - BURREN JUNCTION N1341 COLLARENEBRI - TCHUNINGA N1100 GLENROY - TYCANNAH CREEK N0103 ROWENA - OREEL N2625 BOOMI ROAD - GOONDIWINDI N0268 KILLAWARRA-PALLAMALLAWA N0492 FEEDER SERVICE TO MOREE SCHOOLS N0553 BOGGABRI - GUNNEDAH NO 1 N0605 WARRAGRAH - BOGGABRI N2624 OSTERLEY-BOGGABILLA-GOONDIWINDI N2053 GOOLHI - GUNNEDAH N2235 GUNNEDAH - MULLALEY - TAMBAR SPRINGS N2236 GUNNEDAH - BLACK JACK ROAD N0868 ORANGE GROVE - NARRABRI N2485 BLUE NOBBY - YETMAN N2486 BURWOOD DOWNS - YETMAN N0571 BARDIN - CROPPA CREEK N0252 BAAN BAA - NARRABRI N0603 LINDONFIELD - KYLPER - NARRABRI N0532 GUNNEDAH - WEAN N0921 GUNNEDAH - WONDOBAH ROAD - BOOL N1832 FLORIDA - GUNNEDAH N2204 PIALLAWAY - GUNNEDAH N2354 CARROLL - GUNNEDAH N2563 WILLALA - GUNNEDAH N2134 GWABEGAR TO PILLIGA SCHOOL BUS N0105 NORTH STAR/NOBBY PARK N0524 INVERELL - ARRAWATTA ROAD N0588 LYNWOOD - GILGAI N1070 GLEN ESK - INVERELL N1332 'GRAMAN' - INVERELL N1364 BELLVIEW BOX - INVERELL N1778 INVERELL - WOODSTOCK N1798 BISTONVALE - INVERELL N2759 BONANZA - NORTH STAR N2819 ASHFORD CENTRAL SCHOOL N1783 TULLOONA BORE - MOREE N1838 CROPPA CREEK - MOREE N0849 ARULUEN - YAGOBIE - PALLAMALLAWA N1801 MOREE - BERRIGAL CREEK N0374 MT NOMBI - MULLALEY N0505 GOOLHI - MULLALEY N1345 TIMOR - BLANDFORD N0838 NEILREX TO BINNAWAY N1703 CAROONA - EDGEROI - NARRABRI N1807 BUNNOR - MOREE N1365 TALLAWANTA-BENGERANG-GARAH -

OGW-30-20 Werris Creek

Division / Business Unit: Safety, Engineering & Technology Function: Operations Document Type: Guideline Network Information Book Hunter Valley North Werris Creek (inc) to Turrawan (inc) OGW-30-20 Applicability Hunter Valley Publication Requirement Internal / External Primary Source Local Appendices North Volume 4 Route Access Standard – Heavy Haul Network Section Pages H3 Document Status Version # Date Reviewed Prepared by Reviewed by Endorsed Approved 2.1 18 May 2021 Configuration Configuration Manager GM Technical Standards Management Manager Standards Administrator Amendment Record Amendment Date Clause Description of Amendment Version # Reviewed 1.0 23 Mar 2016 Initial issue 1.1 12 Oct 2016 various Location Nea clause 2.5 removed and Curlewis frame G updated. Diagrams for Watermark, Gap, Curlewis, Gunnedah, Turrawan & Boggabri updated. © Australian Rail Track Corporation Limited (ARTC) Disclaimer This document has been prepared by ARTC for internal use and may not be relied on by any other party without ARTC’s prior written consent. Use of this document shall be subject to the terms of the relevant contract with ARTC. ARTC and its employees shall have no liability to unauthorised users of the information for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of an unauthorised user using or relying upon the information in this document, whether caused by error, negligence, omission or misrepresentation in this document. This document is uncontrolled when printed. Authorised users of this document should visit ARTC’s intranet or extranet (www.artc.com.au) to access the latest version of this document. CONFIDENTIAL Page 1 of 54 Werris Creek (inc) to Turrawan (inc) OGW-30-20 Table of Contents 1.2 11 May 2018 Various Gunnedah residential area signs and new Boggabri Coal level crossings added. -

Railway Safety Investigation Report Baan Baa 4 May 2004

Railway Safety Investigation Report Baan Baa 4 May 2004 Road Motor Vehicle Struck by Countrylink Xplorer Service NP23a on Baranbah Street Level Crossing (530.780kms). 4 May 2004: Road Motor Vehicle Struck by Countrylink Xplorer Passenger Service NP23a on Baranbah Street Level Crossing (530.780kms) 3 Investigation Report Railway Safety Investigation – Baan Baa Published by The Office of Transport Safety Investigation (OTSI) Issue Date: 24th February 2005 Reference Number: 02048 4 May 2004: Road Motor Vehicle Struck by Countrylink Xplorer Passenger Service NP23a on Baranbah Street Level Crossing (530.780kms) 2 Contents Page CONTENTS ............................................................................................................... 3 TABLE OF FIGURES ................................................................................................ 4 PART 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.......................................................................... 5 PART 2 TERMS OF REFERENCE........................................................................ 6 PART 3 INVESTIGATION METHODOLOGY ........................................................ 7 PART 4 FACTUAL INFORMATION ...................................................................... 8 OVERVIEW.............................................................................................................................................8 SEQUENCE OF EVENTS ..........................................................................................................................9 LOSS, -

Outback NSW Regional

TO QUILPIE 485km, A THARGOMINDAH 289km B C D E TO CUNNAMULLA 136km F TO CUNNAMULLA 75km G H I J TO ST GEORGE 44km K Source: © DEPARTMENT OF LANDS Nindigully PANORAMA AVENUE BATHURST 2795 29º00'S Olive Downs 141º00'E 142º00'E www.lands.nsw.gov.au 143º00'E 144º00'E 145º00'E 146º00'E 147º00'E 148º00'E 149º00'E 85 Campground MITCHELL Cameron 61 © Copyright LANDS & Cartoscope Pty Ltd Corner CURRAWINYA Bungunya NAT PK Talwood Dog Fence Dirranbandi (locality) STURT NAT PK Dunwinnie (locality) 0 20 40 60 Boonangar Hungerford Daymar Crossing 405km BRISBANE Kilometres Thallon 75 New QUEENSLAND TO 48km, GOONDIWINDI 80 (locality) 1 Waka England Barringun CULGOA Kunopia 1 Region (locality) FLOODPLAIN 66 NAT PK Boomi Index to adjoining Map Jobs Gate Lake 44 Cartoscope maps Dead Horse 38 Hebel Bokhara Gully Campground CULGOA 19 Tibooburra NAT PK Caloona (locality) 74 Outback Mungindi Dolgelly Mount Wood NSW Map Dubbo River Goodooga Angledool (locality) Bore CORNER 54 Campground Neeworra LEDKNAPPER 40 COUNTRY Region NEW SOUTH WALES (locality) Enngonia NAT RES Weilmoringle STORE Riverina Map 96 Bengerang Check at store for River 122 supply of fuel Region Garah 106 Mungunyah Gundabloui Map (locality) Crossing 44 Milparinka (locality) Fordetail VISIT HISTORIC see Map 11 elec 181 Wanaaring Lednapper Moppin MILPARINKA Lightning Ridge (locality) 79 Crossing Coocoran 103km (locality) 74 Lake 7 Lightning Ridge 30º00'S 76 (locality) Ashley 97 Bore Bath Collymongle 133 TO GOONDIWINDI Birrie (locality) 2 Collerina NARRAN Collarenebri Bullarah 2 (locality) LAKE 36 NOCOLECHE (locality) Salt 71 NAT RES 9 150º00'E NAT RES Pokataroo 38 Lake GWYDIR HWY Grave of 52 MOREE Eliza Kennedy Unsealed roads on 194 (locality) Cumborah 61 Poison Gate Telleraga this map can be difficult (locality) 120km Pincally in wet conditions HWY 82 46 Merrywinebone Swamp 29 Largest Grain (locality) Hollow TO INVERELL 37 98 For detail Silo in Sth. -

Structure and Tectonics of the Gunnedah Basin, N.S.W: Implications for Stratigraphy, Sedimentation and Coal Resources, with Emphasis on the Upper Black Jack Group

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Structure and tectonics of the Gunnedah Basin, N.S.W: implications for stratigraphy, sedimentation and coal resources, with emphasis on the Upper Black Jack group N. Z Tadros University of Wollongong Tadros, N.Z, Structure and tectonics of the Gunnedah Basin, N.S.W: implications for stratigraphy, sedimentation and coal resources, with emphasis on the Upper Black Jack group, PhD thesis, Department of Geology, University of Wollongong, 1995. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/840 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/840 CHAPTER 4 STRUCTURAL ELEMENTS 4.1 Introduction 161 4.2 Basement morphology 161 4.3 Major structural elements 163 4.3.1 Longitudinal and associated structures 163 A. Ridges 163 i) Boggabri Ridge 163 ii) Rocky Glen Ridge 169 B. Shelf areas 169 C. Sub-basins 171 i) Maules Creek Sut)-basin 171 ii) Mullaley Sub-basin 173 iii) Gilgandra Sub-basin 173 4.3.2 Transverse structures and troughs 174 i) Moree and Narrabri Highs; Bellata Trough 174 ii) Walla Walla Ridge; Baradine High; Bohena, Bando, Pilliga and Tooraweena Troughs 176 iii) Breeza Shelf; Bundella and Yarraman Highs 177 iv) Liverpool Structure 180 v) Murrurundi Trough 180 vi) Mount Coricudgy Anticline 182 4.4 Faults 184 4.4.1 Hunter-Mooki Fault System 184 4.4.2 Boggabri Fault 184 4.4.3 Rocky Glen Fault 186 4.5 Minor structures 186 Please see print copy for image Please see print copy for image P l e a s e s e e p r i n t c o p y f o r i m a g e 161 CHAPTER 4 STRUCTURAL ELEMENTS 4.1 INTRODUCTION It has already been mentioned in the previous chapter that the present Gunnedah Basin forms the middle part of the Sydney - Bowen Basin, a long composite stmctural basin, consisting of several troughs defined by bounding basement highs and ridges. -

Attachment Draft 2019/2020 Capital Works Prog

CONSULTATION FOR DRAFT NARRABRI SHIRE COUNCIL'S 2019/2020 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE Capital Funded from: PROGRAM Expenditure Restricted Restricted R/A VPA Draw down Grants & Proceeds from Rates/Chgs, Budget Assets (Int) Assets (Ext) Contributions Loan Funds Contributions Sale of Assets Untied Grants CORPORATE SERVICES Information Services Replace Desktop Computers with Laptops 20,000 20,000 Connect Depot with Fibre Optic 100,000 100,000 Smart Board 7,500 7,500 Upgrade Desktop Computers in Narrabri, Wee Waa and Boggabri Libraries 37,800 37,800 Upgrade CAD Computers 15,000 15,000 Connect Narrabri Waste Facilities to Admin via Wireless Link (Microwave) 25,000 25,000 Upgrade Narrabri CBD CCTV System (carryover 2018/19 + grant funding) 150,505 70,000 80,505 Total Information Services 355,805 205,300 0 70,000 0 80,505 0 0 Property Services Council Rental Property Improvements 15,000 15,000 Energy Sustainability Project – Stage 2 120,000 120,000 97 Cowper Street, Wee Waa – Relevelling of Building 15,000 15,000 Key Management System – Stage 2 & 3 10,000 10,000 Narrabri Library External Painting 15,000 15,000 Administration Building Refurbishment – Stage 2 (Western Wing) 160,000 160,000 Loan Repayments (Staff Housing & Toilets) 77,162 77,162 Total Property & Assets 412,162 205,000 0 0 0 0 0 207,162 Depots Narrabri Depot – Office Workplace Improvements 150,000 150,000 Boggabri & Wee Waa CCTV Cameras 20,000 20,000 Wee Waa Depot – Wash Bay 30,000 30,000 Total Depots 200,000 200,000 0 0 0 0 0 0 Airport CONSULTATION Replace Aerodrome Frequency Response Unit -

NAR-CCC Meeting Minutes and Environmental Monitoring Report 2020 3.6 MB

Narrabri Mine Community Consultative Committee Meeting # 48 Date: Tuesday 04th March 2020 Time: 5:00pm Location: Narrabri Mine office Present: Russel Stewart (RS) Peter Webb (PW) James Steiger (JS) Allan Grumley (AG) Ian Duffy (ID) Charlie Melbourne (CM) Steve Bow (SB) – Narrabri Coal – General Manager David Ellwood (DE) – Narrabri Coal – Director Stage 3 Project Brent Baker (BB) – Narrabri Coal - Environmental Superintendent Gerald Linde (GL)- Narrabri Coal- General Manager Apologies: Mark Foster Cameron Staines 1. DECLARATION OF PECUNIARY INTEREST AG advised he leases properties from Narrabri Coal Operations (NCO) 2. PREVIOUS MINUTES RS moved that previous minutes are accepted as an accurate record. Moved: JS Seconded: PW 2.1 BUSINESS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MINUTES Nil 3. OPERATIONS PROGRESS REPORT AND SAFETY UPDATE Presented by GL Mine Progress Report (01 December 2019 – 29 February 2020) Coal produced (t): February 2020 638,836 FY-to-date 3,587,576 Coal Railed (t): February 2020 767,541 FY-to-date 3,723,728 Narrabri Coal Operations Pty Ltd ABN 76 107 813 963 10 Kurrajong Road, Baan Baa NSW 2390 | P 02 6794 4755 | F 02 6794 4753 WHITEHAVENCOAL.COM.AU Locked Bag 1002, Narrabri NSW 2390 Workforce Average workforce numbers (February 2020): NCO Waged – 152 Salary – 125 Total – 277 Contractors Total – 191 Since January 2019 we have transitioned the following from contractor firms to Whitehaven; - 7 Fitters - 3 Electricians - 30 Operators (3 indigenous workers) Latest clean-skin recruitment program; - December 2019 – Inexperienced Operator advertisement attracted 1257 applicants Australia wide - January 2020 – 27 people shortlisted for assessment - February 2020 – 21 persons invited to interview. -

Information Pack MANAGER PROPERTY SERVICES CONTACT Gemma Sheridan | Talent Consultant, Leading Roles

Information Pack MANAGER PROPERTY SERVICES CONTACT Gemma Sheridan | Talent Consultant, Leading Roles M: 0407 009 243 E: [email protected] www.leadingroles.com.au ABN: 53 142 460 357 Privacy Information: Leading Roles is collecting your personal information in accordance with the Information Privacy Act for the purpose of assessing your skills and experience against the position requirements. The information you provide in your application will only be used by employees of Leading Roles. Your information will be provided to authorised Council Ofcers, including Human Resources and the relevant selection panel members. But it will not be given to any other person or agency unless you have given us permission, or we are required by law. CONTENTS THE PERSON AND THE POSITION 6 KEY SELECTION CRITERIA 9 SELECTION AND SHORTLISTING 10 ORGANISATIONAL CHART 11 COUNCIL VISION 12 OUR STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS 12 OUR COUNCILLORS 15 OUR SHIRE 17 BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY 18 EDUCATION 22 LIFESTYLE 23 LOCAL FESTIVALS AND EVENTS 24 SPORT IN OUR SHIRE 25 OTHER TOWNS 28 Narrabri Shire Information Pack Manager Property Services 3 A NOTE FROM THE General Manager 4 Narrabri Shire Information Pack Manager Property Services Narrabri Shire has taken the first steps into an unprecedented period of growth and never seen before levels of investment. It is exciting times! We have a strong and proud agricultural history that has water meter fleet has operated wirelessly for a number seen numerous major industries develop and expand of years now and we have expended this network to in the Shire, the latest being a greater than $90 million include a series of remote weather stations, and we have redevelopment of the Cotton Seed Distributors site implemented an online training platform that integrates encompassing processing plants with world leading with the HR modules of TechnologyOne. -

New South Wales Centenary of Federation Project

0292 New South Wales Centenary of Federation Project ‘Preserving People’s Parishes’ Undertaken by the Society of Australian Genealogists With permission of The Diocesan Council, Anglican Diocese of Armidale Registers of the Anglican Parish of Baradine Frame Numbers 1. Baptisms: 22nd February, 1920 – 4th January, 1931 006-028 NOTE: In this register the name changes from ‘Pilliga’ to ‘Baradine’ 1926/1927. This register is housed at the Anglican Church, Wee Waa 2. Baptisms: 1st March, 1915 – 22nd February, 1931 030-057 NOTE: There is a gap in the register after April, 1921 and before February, 1924 This register is housed at the Anglican Church, Wee Waa 3. Marriages: 1920 – 1930 058-073 At: Union Church, Baradine; St Paul’s Church, Baradine; St John’s Church, Pillaga; Church of England, Burren Junction; Presbyterian Church, Gwabegar; St Peter’s Cathedral, Armidale; The Aborigines Mission Station, Pilliga Private Residences: ‘Anawa’, Baradine; ‘Kanowana’, Baradine; Bugaldie; ‘Cumbil’, Baradine; Baradine; Pillaga; ‘Kyogle’, Pillaga; Come by Chance Hall This register is housed at the Anglican Church, Wee Waa Microfilmed by W & F Pascoe for the Society of Australian Genealogists 2001 This microfilm is supplied for information and research purposes only. Copying of individual frames is permitted. New South Wales Centenary of Federation Project ‘Preserving People’s Parishes’ Registers of the Anglican Parish of Baradine (continued) Frame Numbers 4. Burials: 23rd February, 1920 – 31st October, 1942 074-089 No records to be found c. 1931-1936 ie [Last record for 1931 is 19th August; First record for 1936 is 15th June] Plus: Certificate of Coroner or Justice of the Peace ordering burial 089 23rd October, 1942 of Robert James Turvey Places of Burial Include: Coonabarabran; Pilliga; Gwabegar; Pilliga Aboriginal Missions Cemetery This register is housed at the Anglican Church, Wee Waa 5. -

Woodsreef State Conservation Area (331 Hectares) Locationlocation of Woodsreef CCA Zone 3 State Conservation Area

Woodsreef State Conservation Area (331 hectares) LocationLocation of Woodsreef CCA Zone 3 State Conservation Area Moree ! Bingara ! Pilliga ! Narrabri ! Woodsreef ! Gwabegar Baradine ! Gunnedah ! ! Tamworth ! Coonabarabran Quirindi ! ! Dubbo ! Woodsreef State Conservation Area Other Zone 3 State Conservation Areas 0 Km 60 Spatial data courtesy of Office of Environment and Heritage. ± Ref: U:\MXDS\Brigalow Nandewar project 2014-18\REPORT\CCAZ3 location\Woodsreef - Location - Brigalow and Nandewar.mxd 238 Natural Resources Commission Woodsreef State Conservation Area AerialWoodsreef State Conservation Area Aerial Woodsreef State Conservation Area boundary ADS40 Airborne Digital Sensor data. Spatial data courtesy of Office of Environment and Heritage. 0 Km 0.5 Spatial analysis by Remote Census Pty Ltd (2014). ± Ref: U:\MXDS\Brigalow Nandewar project 2014-18\REPORT\Aerial - ADS40 - RGB TIFF\Woodsreef - ADS40 RGB TIFF - Brigalow and Nandewar.mxd Profiles - Brigalow and Nandewar State Conservation Areas (Zone 3) 239 Woodsreef State Conservation Area Predicted location - white cypress pine Woodsreef State Conservation Area Predicted location - white cypress pine Relative probability (%) of white cypress pine occurence 0 - 10 10 - 20 20 - 30 30 - 40 40 - 50 50 - 60 60 - 70 70 - 80 80 - 90 90 - 100 Woodsreef State Conservation Area boundary Spatial data courtesy of Office of Environment and Heritage. 0 Km 0.5 Spatial analysis by Eco Logical Australia Pty Ltd. ± Document Path: U:\MXDS\Brigalow Nandewar project 2014-18\FINAL REPORT\WCP - Predicted\Woodsreef - WCP - Predicted location - Ecological - Brigalow and Nandewar.mxd 240 Natural Resources Commission Woodsreef State Conservation Area Predicted location - black cypress pine Woodsreef State Conservation Area Predicted location - black cypress pine Relative probability (%) of black cypress pine occurence 0 - 10 10 - 20 20 - 30 30 - 40 40 - 50 50 - 60 60 - 70 70 - 80 Woodsreef State Conservation Area boundary Spatial data courtesy of Office of Environment and Heritage. -

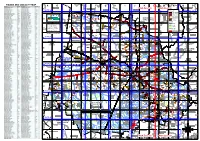

Roads and Locality Map 1010 1111 Oo

ROADS AND LOCALITY MAP AA BB CC DD EE FF GG HH II JJ KK LL MM NN OO PP ROWENAROWENA MGAMGA ZoneZone 5555 MGAMGA ZoneZone 5656 GRAGRAVESENDVESEND 11 MAMALLOWALLOWA MGAMGA ZoneZone 5555 MGAMGA ZoneZone 5656 11 29.75°29.75° SS MILLIEMILLIE GURLEYGURLEY 29.75°29.75° SS GURLEYGURLEY TransportTransport StateState HighwayHighway SR221 StateState HighwayHighway POISON GATE ROAD Creek MajorMajor SealedSealed SR1 Doorabeeba SR255 MILLIE ROAD MinorMinor SealedSealed CLARENDON ROAD TERRYTERRY Creek Thalaba SR80 RBulyeroi Millie GUNADOO LANE MajorMajor UnsealedUnsealed Creek Bore Creek Creek HIEHIE Bumble HIEHIE MinorMinor UnsealedUnsealed ELCOMBEELCOMBE Creek MinorMinor UnsealedUnsealed ELCOMBEELCOMBE Waterloo SH17 MinorMinor UnsealedUnsealed ELCOMBEELCOMBE Millie SR1 BULYEROIBULYEROI MILLIE ROAD Little NEWELL HIGHWAY MOREE PLAINS SR45 Pidgee SR269 NaturalNatural SurfaceSurface Waterhole HIEHIE NaturalNatural SurfaceSurface 22 NOWLEY ROAD BRIGALOW LANE 22 Thalaba Creek RailwayRailway Millie Waterloo SHIRE COUNCIL RailwayRailway Creek Creek LocalityLocality SR4 R Bunna SPRING PLAINS ROAD Creek SR280 #2 Bore JEWSJEWS LAGOONLAGOON SR107 Creek MANAMOI ROAD RegionRegion SR197 Gehan Tookey WAIWERA LANE DISCLAIMER SUNNYSIDE ROAD BANGHEETBANGHEET SR278 All care is taken in the preparation CAMERONS SR9 StateState ForestForest of this plan, however, Narrabri Shire Council BALD HILL ROAD StateState ForestForest LANE SR283 Gehan accepts no responsibility for any misprints, SR1 MILTON DOWNS ROAD SR113 errors, omissions or inaccuracies. MILLIE ROAD RegionRegion -

Submission from Stop CSG Sydney on the Santos Narrabri Project Environmental Impact Statement

Submission from Stop CSG Sydney on the Santos Narrabri Project Environmental Impact Statement About Stop CSG Sydney Stop Coal Seam Gas Sydney was formed in 2011 by residents of the inner west suburbs of Sydney following their discovery that Dart Energy was about to explore for coal seam gas in St Peters, just 7kms from the CBD. The company had an exploration licence (PEL 463) covering not only the whole of metropolitan Sydney but as far as Gosford in the north and Sutherland in the south. The licence was cancelled by the Baird government in March 2015 following a strong community campaign against coal seam gas exploration and mining in the region. Stop CSG Sydney has continued to campaign against unconventional gas development in NSW and we strongly object to the Santos Narrabri Project. Grounds for our opposition to the Project The project would cause trauma to the traditional custodians of the Pilliga This proposal exposes the company’s misconception about the importance of the Pilliga to the Gomeroi/Gamilaraay people. We support the submissions of the traditional owners of the land that the Pilliga as a whole is central to preservation of their culture and connection to country. The company may pretend the situation is one where “heritage” sites and artefacts need to be “avoided” by their operations. Protecting Aboriginal sacred sites and the forest as a whole from mining and invasive infrastructure is critical to the Gamilaraay people and to their future. Industrialisation of the Pilliga would be totally contrary to the rights, cultural responsibilities and needs of the Gamilaraay people.