Nowitna National Wildlife Refuge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Alaska Fire Season

2012 ALASKA FIRE SEASON Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report – AICC Photo Courtesy of Don York Table of Contents 1 Index 2 2012 Alaska Fire Season Summary 11 2012 Fires over 1,000 acres 12 2012 Statewide Fires and Acres Burned by Protection Agency and Management Option 13 2012 Statewide Fires and Acres Burned by Landowner and Management Option 14 2012 Fires Burned by Landowner and Management Graph 15 2012 Acres Burned by Landowner and Management Graph 16 2012 Statewide Acres Burned by Landowner in Critical Management Option Graph 17 2012 Statewide Acres Burned by Landowner in Full Management Option Graph 18 2012 Statewide Acres Burned by Landowner in Modified Management Option Graph 19 2012 Statewide Acres Burned by Landowner in Limited Management Option Graph 20 2012 Alaska Fire Service Protection Fires and Acres Burned by Zone and Management Option 20 2012 USFS Fire and Acres burned by Forest 21 2012 State of Alaska Protection Fires and Acres burned by Region and Management Option 22 2012 BLM Fires and Acres Burned by landowner and Management Option 22 2012 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fires and Acres Burned by Refuge and Management Option 23 2012 National Park Service Fire and Acres burned by Park ort preserve and Management Option 24 2012 Wildfires by Cause and Size Class 25 2012 EFF wages 1 2012 Alaska Fire Season Summary APRIL/MAY The 2012 Alaska fire Season started with a warm and dry April, burning less than 12 acres with 20 fires by month’s end. A cool May, with precipitation at the end of the month, slowed Alaska’s pace to 200 acres burned, whereas in 2011 nearly 140,000 acres had burned in May. -

COURSE NAME CITY STATE ALBERTVILLE GOLF & COUNTRY CLUB Albertville Alabama MOUNTAIN VIEW GOLF COURSE Alden Alabama LAKEWINDS

COURSE NAME CITY STATE ALBERTVILLE GOLF & COUNTRY CLUB Albertville Alabama MOUNTAIN VIEW GOLF COURSE Alden Alabama LAKEWINDS GOLF COURSE Alex City Alabama WILLOW POINT COUNTRY CLUB Alex City Alabama ALPINE BAY GOLF CLUB Alpine Alabama WHIPPORWHILL GOLF COURSE Altoona Alabama ANDALUSIA COUNTRY CLUB Andalusia Alabama EVANS BARNES GOLF COURSE Andalusia Alabama ANDERSON CREEK GOLF COURSE Anderson Alabama ANNISTON COUNTRY CLUB Anniston Alabama ANNISTON MUNICIPAL GOLF COURSE Anniston Alabama B & J GOLF CENTER Anniston Alabama CANE CREEK GOLF COURSE Anniston Alabama CIDER RIDGE GOLF CLUB Anniston Alabama INDIAN OAKS GOLF CLUB Anniston Alabama PINE HILL COUNTRY CLUB Anniston Alabama BROOKSIDE GOLF COURSE Arab Alabama TWIN LAKES GOLF CLUB Arab Alabama UNION SPRINGS COUNTRY CLUB Armstrong Alabama CLAY COUNTY PUBLIC GOLF COURSE Ashland Alabama ATHENS GOLF & COUNTRY CLUB Athens Alabama CANEBRAKE GOLF CLUB Athens Alabama CHRISWOOD GOLF COURSE Athens Alabama SOUTHERN GALES GOLF CLUB Athens Alabama WOODLAND GOLF COURSE Athens Alabama ATMORE COUNTRY CLUB Atmore Alabama WILLS CREEK COUNTRY CLUB Attalla Alabama AUBURN LINKS AT MILL CREEK Auburn Alabama INDIAN PINES RECREATIONAL AUTHORITY Auburn Alabama MOORE'S MILL GOLF CLUB Auburn Alabama MOORE'S MILL GOLF CLUB Auburn Alabama PIN OAKS GOLF CLUB Auburn Alabama EUFAULA COUNTRY CLUB Bakerhill Alabama LAKEPOINT RESORT GOLF COURSE Bakerhill Alabama RED EAGLE GOLF COURSE Bakerhill Alabama WARRIOR POINT GOLF CLUB Barney Alabama HOLLY HILLS COUNTRY CLUB Bay Minette Alabama BENT BROOK GOLF COURSE Bess Alabama -

Fishery Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Yukon Management Area, 2012

Fishery Management Report No. 14-31 Fishery Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Yukon Management Area, 2012 by John Burr June 2014 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative all standard mathematical deciliter dL Code AAC signs, symbols and gram g all commonly accepted abbreviations hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. base of natural logarithm e kilometer km all commonly accepted catch per unit effort CPUE liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., coefficient of variation CV meter m R.N., etc. common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) milliliter mL at @ confidence interval CI millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient east E (multiple) R Weights and measures (English) north N correlation coefficient cubic feet per second ft3/s south S (simple) r foot ft west W covariance cov gallon gal copyright degree (angular ) ° inch in corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df mile mi Company Co. expected value E nautical mile nmi Corporation Corp. -

March 1St, 2021 Snow Water Equivalent

March 1, 2021 The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service cooperates with the following organizations in snow survey work: Federal State of Alaska U.S. Depart of Agriculture - U.S. Forest Service Alaska Department of Fish and Game Chugach National Forest Alaska Department of Transportation and Tongass National Forest Public Facilities U.S. Department of Commerce Alaska Department of Natural Resources NOAA, Alaska Pacific RFC Division of Parks U.S. Department of Defense Division of Mining and Water U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Division of Forestry U.S. Department of Interior Alaska Energy Authority Bureau of Land Management Alaska Railroad U.S. Geological Survey Soil and Water Conservation Districts U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Homer SWCD National Park Service Fairbanks SWCD Salcha-Delta SWCD Municipalities University of Alaska Anchorage Geophysical Institute Juneau Water and Environment Research Private Alaska Public Schools Alaska Electric, Light and Power, Juneau Mantanuska-Susitna Borough School Alyeska Resort, Inc. District Alyeska Pipeline Service Company Eagle School, Gateway School District Anchorage Municipal Light and Power Chugach Electric Association Canada Copper Valley Electric Association Ministry of the Environment Homer Electric Association British Columbia Ketchikan Public Utilities Department of the Environment Prince William Sound Science Center Government of the Yukon The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, nation- al origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. -

Identification and Characterization of Inconnu Spawning Habitat in the Sulukna River, Alaska

Identification and characterization of inconnu spawning habitat in the Sulukna River, Alaska Item Type Thesis Authors Gerken, Jonathon D. Download date 01/10/2021 17:30:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/6994 IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF INCONNU SPAWNING HABITAT IN THE SULUKNA RIVER, ALASKA By Jonathon Gerken RECOMMENDED: Mr. Randy Bpown h jM k i - ____________________ Dr. David Verbyla C9/ts Dr. Christian Zimmerman _________ , .///A , l Dr. Joseph Margraf, Advisory Committee C^iair 7 fU > Dr. Shannon Atkinson, Interim Director, Fisheries Division APPROVED: Dr. Denis Wiesenburg Dean, SchoaUef Fisheries and Ocean Sciences /Sr DfTLawrence Duffy, Dean of the Graduate School Date IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF INCONNU SPAWNING HABITAT IN THE SULUKNA RIVER, ALASKA A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Jonathon D. Gerken, B.S. Fairbanks, Alaska December 2009 Ill Abstract InconnuStenodus leucichthys are present throughout much of the Yukon Rlver drainage in Alaska, but only five spawning areas have been identified. Spawning habitat requlrements are therefore thought to be very speclflc; however, the physlcal qualltles of these habitats have only been characterized in general terms. The Sulukna River is one of five identified inconnu spawning areas within the Yukon River drainage. A systematic sampling design was used in September and October of 2007-2008 to define Sulukna River spawning locations. Presence of inconnu was identified using hook and line sampling methods and spawning was verified by catching broadcast eggs in plankton nets. Small-scale, large-scale, and chemical habitat variables were sampled at transects located every 1.8 river kilometer (rkm). -

Fishery Management Report No. 00-7

Fishery Management Report No. 00-7 Fishery Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim Management Area from 1995 to 1997 by John Burr June 2000 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Sport Fish FISHERY MANAGEMENT REPORT NO. 00-7 FISHERY MANAGEMENT REPORT FOR SPORT FISHERIES IN THE ARCTIC-YUKON-KUSKOKWIM MANAGEMENT AREA FROM 1995 TO 1997 by John Burr Division of Sport Fish Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Sport Fish, Policy and Technical Services 333 Raspberry Road, Anchorage, Alaska, 99518-1599 June 2000 This investigation was partially financed by the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act (16 U.S.C. 777-777K) under Project F-10-9, F-10-10. The Fishery Management Reports series was established in 1989 for the publication of an overview of Division of Sport Fish management activities and goals in a specific geographic area. Fishery Management Reports are intended for fishery and other technical professionals, as well as lay persons. Fishery Management Reports are available through the Alaska State Library and on the Internet: http://www.sf.adfg.state.ak.us/statewide/divreports/html/intersearch.cfm This publication has undergone regional peer review. John Burr Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Sport Fish 1300 College Rd. Fairbanks, AK 99701-1599, USA This document should be cited as: Burr, J. 2000. Fishery Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim Management Area, 1995 to 1997. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Fishery Management Report No. 00-7, Anchorage. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game administers all programs and activities free from discrimination on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, sex, religion, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. -

Straddling the Arctic Circle in the East Central Part of the State, Yukon Flats Is Alaska's Largest Interior Valley

Straddling the Arctic Circle in the east central part of the State, Yukon Flats is Alaska's largest Interior valley. The Yukon River, fifth largest in North America and 2,300 miles long from its source in Canada to its mouth in the Bering Sea, bisects the broad, level flood- plain of Yukon Flats for 290 miles. More than 40,000 shallow lakes and ponds averaging 23 acres each dot the floodplain and more than 25,000 miles of streams traverse the lowland regions. Upland terrain, where lakes are few or absent, is the source of drainage systems im- portant to the perpetuation of the adequate processes and wetland ecology of the Flats. More than 10 major streams, including the Porcupine River with its headwaters in Canada, cross the floodplain before discharging into the Yukon River. Extensive flooding of low- land areas plays a dominant role in the ecology of the river as it is the primary source of water for the many lakes and ponds of the Yukon Flats basin. Summer temperatures are higher than at any other place of com- parable latitude in North America, with temperatures frequently reaching into the 80's. Conversely, the protective mountains which make possible the high summer temperatures create a giant natural frost pocket where winter temperatures approach the coldest of any inhabited area. While the growing season is short, averaging about 80 days, long hours of sunlight produce a rich growth of aquatic vegeta- tion in the lakes and ponds. Soils are underlain with permafrost rang- ing from less than a foot to several feet, which contributes to pond permanence as percolation is slight and loss of water is primarily due to transpiration and evaporation. -

Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change: Main Report

Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate change Main Report Published By Global Environment Centre, Kuala Lumpur & Wetlands International, Wageningen First Published in Electronic Format in December 2007 This version first published in May 2008 Copyright © 2008 Global Environment Centre & Wetlands International Reproduction of material from the publication for educational and non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior permission from Global Environment Centre or Wetlands International, provided acknowledgement is provided. Reference Parish, F., Sirin, A., Charman, D., Joosten, H., Minayeva , T., Silvius, M. and Stringer, L. (Eds.) 2008. Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change: Main Report . Global Environment Centre, Kuala Lumpur and Wetlands International, Wageningen. Reviewer of Executive Summary Dicky Clymo Available from Global Environment Centre 2nd Floor Wisma Hing, 78 Jalan SS2/72, 47300 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Tel: +603 7957 2007, Fax: +603 7957 7003. Web: www.gecnet.info ; www.peat-portal.net Email: [email protected] Wetlands International PO Box 471 AL, Wageningen 6700 The Netherlands Tel: +31 317 478861 Fax: +31 317 478850 Web: www.wetlands.org ; www.peatlands.ru ISBN 978-983-43751-0-2 Supported By United Nations Environment Programme/Global Environment Facility (UNEP/GEF) with assistance from the Asia Pacific Network for Global Change Research (APN) Design by Regina Cheah and Andrey Sirin Printed on Cyclus 100% Recycled Paper. Printing on recycled paper helps save our natural -

Annual Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim Region, 1987

Fishery Management Report No. 91-1 Annual Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim Region, 1987 William D. Arvey, Michael J. Kramer, Jerome E. Hallberg, James F. Parker, and Alfred L. DeCicco April 1991 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Sport Fish FISHERY MANAGEMENT REPORT NO. 91-1 ANNUAL MANAGEMENT REPORT FOR SPORT FISHERIES IN THE ARCTIC-YUKON-KUSKOKWIM REGION, 1987l William D. Arvey, Michael J. Kramer, Jerome E. Hallberg, James F. Parker, and Alfred L. DeCicco Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Sport Fish Anchorage, Alaska April 1991 Some of the data included in this report were collected under various jobs of project F-10-3 of the Federal Aid in Fish Restoration Act (16 U.S.C. 777-777K). TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES............................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES.............................................. V LIST OF APPENDICES ........................................... vii ABSTRACT ..................................................... 1 PREFACE...................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION................................................. 3 TANANA AREA DESCRIPTION ...................................... 3 Geographic and Geologic Setting ......................... 3 Lake and Stream Development ............................. 10 Climate................................................. 13 Primary Species for Sport Fishing ....................... 13 Status and Harvest Trends of Wild Stocks ................ 13 Chinook Salmon .................................... -

Yukon River Sheefish

Fishery Management Report No. 15-51 Fishery Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Yukon Management Area, 2014 by April Behr Brendan Scanlon and Klaus Wuttig December 2015 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative all standard mathematical deciliter dL Code AAC signs, symbols and gram g all commonly accepted abbreviations hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. base of natural logarithm e kilometer km all commonly accepted catch per unit effort CPUE liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., coefficient of variation CV meter m R.N., etc. common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) milliliter mL at @ confidence interval CI millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient east E (multiple) R Weights and measures (English) north N correlation coefficient cubic feet per second ft3/s south S (simple) r foot ft west W covariance cov gallon gal copyright degree (angular ) ° inch in corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df mile mi Company Co. -

Muskeg (Global Rank G4G5; State Rank S4)

Muskeg (Global Rank G4G5; State Rank S4) Overview: Distribution, Abundance, times present, and these may be ringed by narrow aprons of Environmental Setting, Ecological Processes Poor Fen where the vegetation has direct contact with sur- “Muskeg” is a term of Algonquian origin translating roughly face waters and Muskeg (or conifer swamp) farther from the to “grassy bog” or “moss bog.” It does not have a precise sci- water’s edge. Stands of Muskeg vary in size from a few acres entific meaning, but as defined here it is an ombrotrophic to huge peatland complexes encompassing thousands of acres or very weakly minerotrophic acid peatland community and are most often associated with landforms such as glacial characterized by a substrate of moss hummocks and a thin outwash or lakebeds and sometimes ground moraine. scattering of stunted swamp conifers. Muskeg is floristically As peat accumulates, the plant community is increasingly similar to Open Bog but differs structurally in the greater isolated from mineral-enriched groundwater, and conditions presence and higher cover of conifers. Extensive openings favorable for the persistence of more nutrient-demanding devoid of trees are absent. This basic structural difference vascular herbs and tree growth decline. Unless site hydrology plays an important role in providing preferred habitat for is significantly altered, highly acidic sphagnum peat increases many animals, for example, birds and invertebrates. Shading while tree cover is likely to very slowly diminish. See Crum is higher in Muskeg than in Open Bog or in any of the open (1988) for a detailed discussion of fen to bog succession. Few northern fen communities, which affects the proportions data from Wisconsin are available on water chemistry and of the plant species comprising the community. -

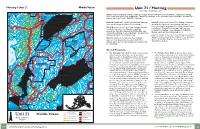

Hunting / Unit 21 Middle Yukon Unit 21 / Hunting (See Unit 21 Middle Yukon Map)

(See Unit 21 Middle Yukon map) +XJKHV Unit 21 consists of drainages into the Yukon River upstream from Paimiut to (but excluding) the Tozitna River drainage &DQGOH %XFNODQG on the north bank; and to (but excluding) the Tanana River drainage on the south bank; and excluding the Koyukuk River drainage upstream from the Dulbi River drainage. +XVOLD Unit 21A consists of the Innoko River drainage upstream Unit 21D consists of the Yukon River drainage from (and from (and including) the Iditarod River drainage. including) the Blackburn Creek drainage upstream to Ruby; including the area west of the Ruby-Poorman Road; Unit 21B consists of the Yukon River drainage upstream excluding the Koyukuk River drainage upstream from from Ruby and east of the Ruby-Poorman Road; 7DQDQD the Dulbi River drainage; and excluding the Dulbi River downstream from (but excluding) the Tozitna River and drainage upstream from Cottonwood Creek. Tanana River drainages; and excluding the Melozitna River drainage upstream from Grayling Creek. Unit 21E consists of the Yukon River drainage from Paimiut .R\XN upstream to (but excluding) the Blackburn Creek drainage; .R\XNXN Unit 21C consists of the Melozitna River drainage and the Innoko River drainage downstream from the upstream from Grayling Creek; and the Dulbi River 1XODWR *DOHQD Iditarod River drainage. 5XE\ drainage upstream from (and including) the Cottonwood Creek drainage. 6KDNWRROLN .DOWDJ Special Provisions ● The Koyukuk Controlled Use Area is closed during ● The Paradise Controlled Use Area is closed during 3RRUPDQ moose hunting seasons to the use of aircraft for moose hunting seasons to the use of aircraft for hunting hunting moose, including transportation of any moose moose, including transportation of any moose hunter 8QDODNOHHW hunter or moose part.