Metamorphosis Issn 1018- 6409

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetic Relationships and Historical Biogeography of Tribes and Genera in the Subfamily Nymphalinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKBIJBiological Journal of the Linnean Society 0024-4066The Linnean Society of London, 2005? 2005 862 227251 Original Article PHYLOGENY OF NYMPHALINAE N. WAHLBERG ET AL Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2005, 86, 227–251. With 5 figures . Phylogenetic relationships and historical biogeography of tribes and genera in the subfamily Nymphalinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) NIKLAS WAHLBERG1*, ANDREW V. Z. BROWER2 and SÖREN NYLIN1 1Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Zoology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331–2907, USA Received 10 January 2004; accepted for publication 12 November 2004 We infer for the first time the phylogenetic relationships of genera and tribes in the ecologically and evolutionarily well-studied subfamily Nymphalinae using DNA sequence data from three genes: 1450 bp of cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) (in the mitochondrial genome), 1077 bp of elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1-a) and 400–403 bp of wing- less (both in the nuclear genome). We explore the influence of each gene region on the support given to each node of the most parsimonious tree derived from a combined analysis of all three genes using Partitioned Bremer Support. We also explore the influence of assuming equal weights for all characters in the combined analysis by investigating the stability of clades to different transition/transversion weighting schemes. We find many strongly supported and stable clades in the Nymphalinae. We are also able to identify ‘rogue’ -

Title Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Amet, Consectetur Adipiscing Elit

Volume 26: 102–108 METAMORPHOSIS www.metamorphosis.org.za ISSN 1018–6490 (PRINT) LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY OF AFRICA ISSN 2307–5031 (ONLINE) Classification of the Afrotropical butterflies to generic level Published online: 25 December 2015 Mark C. Williams 183 van der Merwe Street, Rietondale, Pretoria, South Africa. E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © Lepidopterists’ Society of Africa Abstract: This paper applies the findings of phylogenetic studies on butterflies (Papilionoidea) in order to present an up to date classification of the Afrotropical butterflies to genus level. The classification for Afrotropical butterflies is placed within a worldwide context to subtribal level. Taxa that still require interrogation are highlighted. Hopefully this classification will provide a stable context for researchers working on Afrotropical butterflies. Key words: Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea, Afrotropical butterflies, classification. Citation: Williams, M.C. (2015). Classification of the Afrotropical butterflies to generic level. Metamorphosis 26: 102–108. INTRODUCTION Suborder Glossata Fabricius, 1775 (6 infraorders) Infraorder Heteroneura Tillyard, 1918 (34 Natural classifications of biological organisms, based superfamilies) on robust phylogenetic hypotheses, are needed before Clade Obtectomera Minet, 1986 (12 superfamilies) meaningful studies can be conducted in regard to their Superfamily Papilionoidea Latreille, 1802 (7 evolution, biogeography, ecology and conservation. families) Classifications, dating from the time of Linnaeus in the Family Papilionidae Latreille, 1802 (32 genera, 570 mid seventeen hundreds, were based on morphology species) for nearly two hundred and fifty years. Classifications Family Hedylidae Guenée, 1858 (1 genus, 36 species) based on phylogenies derived from an interrogation of Family Hesperiidae Latreille, 1809 (570 genera, 4113 the genome of individual organisms began in the late species) 20th century. -

African Butterfly News Can Be Downloaded Here

LATE SUMMER EDITION: JANUARY / AFRICAN FEBRUARY 2018 - 1 BUTTERFLY THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY OF AFRICA NEWS LATEST NEWS Welcome to the first newsletter of 2018! I trust you all have returned safely from your December break (assuming you had one!) and are getting into the swing of 2018? With few exceptions, 2017 was a very poor year butterfly-wise, at least in South Africa. The drought continues to have a very negative impact on our hobby, but here’s hoping that 2018 will be better! Braving the Great Karoo and Noorsveld (Mark Williams) In the first week of November 2017 Jeremy Dobson and I headed off south from Egoli, at the crack of dawn, for the ‘Harde Karoo’. (Is there a ‘Soft Karoo’?) We had a very flexible plan for the six-day trip, not even having booked any overnight accommodation. We figured that finding a place to commune with Uncle Morpheus every night would not be a problem because all the kids were at school. As it turned out we did not have to spend a night trying to kip in the Pajero – my snoring would have driven Jeremy nuts ... Friday 3 November The main purpose of the trip was to survey two quadrants for the Karoo BioGaps Project. One of these was on the farm Lushof, 10 km west of Loxton, and the other was Taaiboschkloof, about 50 km south-east of Loxton. The 1 000 km drive, via Kimberley, to Loxton was accompanied by hot and windy weather. The temperature hit 38 degrees and was 33 when the sun hit the horizon at 6 pm. -

Duke University Dissertation Template

Evolutionary trends in phenotypic elements of seasonal forms of the tribe Junoniini (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) by Jameson Wells Clarke Department of Biology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ H. Fred Nijhout, Ph.D., Supervisor ___________________________ V. Louise Roth, Ph.D. ___________________________ Sonke Johnsen, Ph.D. Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Biology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 i v ABSTRACT Evolutionary trends in phenotypic elements of seasonal forms of the tribe Junoniini (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) by Jameson Wells Clarke Department of Biology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ H. Fred Nijhout, Ph.D., Supervisor ___________________________ V. Louise Roth, Ph.D. ___________________________ Sonke Johnsen, Ph.D. An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Biology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Jameson Wells Clarke 2017 Abstract Seasonal polyphenism in insects is the phenomenon whereby multiple phenotypes can arise from a single genotype depending on environmental conditions during development. Many butterflies have multiple generations per year, and environmentally induced variation in wing color pattern phenotype allows them to develop adaptations to the specific season in which the adults live. Elements of butterfly -

The Butterflies of Taita Hills

FLUTTERING BEAUTY WITH BENEFITS THE BUTTERFLIES OF TAITA HILLS A FIELD GUIDE Esther N. Kioko, Alex M. Musyoki, Augustine E. Luanga, Oliver C. Genga & Duncan K. Mwinzi FLUTTERING BEAUTY WITH BENEFITS: THE BUTTERFLIES OF TAITA HILLS A FIELD GUIDE TO THE BUTTERFLIES OF TAITA HILLS Esther N. Kioko, Alex M. Musyoki, Augustine E. Luanga, Oliver C. Genga & Duncan K. Mwinzi Supported by the National Museums of Kenya and the JRS Biodiversity Foundation ii FLUTTERING BEAUTY WITH BENEFITS: THE BUTTERFLIES OF TAITA HILLS Dedication In fond memory of Prof. Thomas R. Odhiambo and Torben B. Larsen Prof. T. R. Odhiambo’s contribution to insect studies in Africa laid a concrete footing for many of today’s and future entomologists. Torben Larsen’s contribution to the study of butterflies in Kenya and their natural history laid a firm foundation for the current and future butterfly researchers, enthusiasts and rearers. National Museums of Kenya’s mission is to collect, preserve, study, document and present Kenya’s past and present cultural and natural heritage. This is for the purposes of enhancing knowledge, appreciation, respect and sustainable utilization of these resources for the benefit of Kenya and the world, for now and posterity. Copyright © 2021 National Museums of Kenya. Citation Kioko, E. N., Musyoki, A. M., Luanga, A. E., Genga, O. C. & Mwinzi, D. K. (2021). Fluttering beauty with benefits: The butterflies of Taita Hills. A field guide. National Museums of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya. ISBN 9966-955-38-0 iii FLUTTERING BEAUTY WITH BENEFITS: THE BUTTERFLIES OF TAITA HILLS FOREWORD The Taita Hills are particularly diverse but equally endangered. -

Acacia Flat Mite (Brevipalpus Acadiae Ryke & Meyer, Tenuipalpidae, Acarina): Doringboomplatmyt

Creepie-crawlies and such comprising: Common Names of Insects 1963, indicated as CNI Butterfly List 1959, indicated as BL Some names the sources of which are unknown, and indicated as such Gewone Insekname SKOENLAPPERLYS INSLUITENDE BOSLUISE, MYTE, SAAMGESTEL DEUR DIE AALWURMS EN SPINNEKOPPE LANDBOUTAALKOMITEE Saamgestel deur die MET MEDEWERKING VAN NAVORSINGSINSTITUUT VIR DIE PLANTBESKERMING TAALDIENSBURO Departement van Landbou-tegniese Dienste VAN DIE met medewerking van die DEPARTEMENT VAN ONDERWYS, KUNS EN LANDBOUTAALKOMITEE WETENSKAP van die Taaldiensburo 1959 1963 BUTTERFLY LIST Common Names of Insects COMPILED BY THE INCLUDING TICKS, MITES, EELWORMS AGRICULTURAL TERMINOLOGY AND SPIDERS COMMITTEE Compiled by the IN COLLABORATION WiTH PLANT PROTECTION RESEARCH THE INSTITUTE LANGUAGE SERVICES BUREAU Department of Agricultural Technical Services OF THE in collaboration with the DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, ARTS AND AGRICULTURAL TERMINOLOGY SCIENCE COMMITTEE DIE STAATSDRUKKER + PRETORIA + THE of the Language Service Bureau GOVERNMENT PRINTER 1963 1959 Rekenaarmatig en leksikografies herverwerk deur PJ Taljaard e-mail enquiries: [email protected] EXPLANATORY NOTES 1 The list was alphabetised electronically. 2 On the target-language side, ie to the right of the :, synonyms are separated by a comma, e.g.: fission: klowing, splyting The sequence of the translated terms does NOT indicate any preference. Preferred terms are underlined. 3 Where catchwords of similar form are used as different parts of speech and confusion may therefore -

Rediscovery of the Threatened Stoffberg Widow Butterfly, Dingana Fraterna: the Value of Citizen Scientists for African Conservation

Rediscovery of the threatened Stoffberg Widow butterfly, Dingana fraterna: The value of citizen scientists for African conservation James M. Lawrence Research Fellow Department of Environmental Sciences, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, University of South Africa email: [email protected] Abstract The Stoffberg Widow, Dingana fraterna (Lepidoptera: Satyrinae), was only known from a single highly localised population near Stoffberg, South Africa. This butterfly is univoltine, with historical records indicating that adults fly for approximately 10 days in early October. It was last seen in 2002 and was Red-Listed as Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct). The cause of the extirpation of the type population was inappropriate burning of its habitat during the adult flight period. A new colony was recently discovered in October 2014 at a site 46 km N of the type locality by citizen scientists from the Lepidopterists' Society of Africa. This study clearly highlights that developing countries, which are often limited in resources, can benefit hugely from the contributions of citizen scientists to conservation initiatives. Keywords Conservation; COREL; Critically Endangered; Lepidopterests' Society of Africa Insects form the most species-rich group of land animals. Following increased awareness of the vital functions they perform in many ecosystems, their conservation has assumed considerable worldwide importance (New 2012). Butterflies, being the most popular of the invertebrate groups, have often 1 been the focus of such conservation projects. South Africa, with its high levels of invertebrate endemism, has not lagged far behind these worldwide initiatives (Ball 2012). Following the establishment of the Lepidopterists' Society of Africa (LepSoc) in 1983, the conservation of African butterflies, especially those endemic to southern Africa, has been well publicised (e.g. -

The Biodiversity of Atewa Forest

The Biodiversity of Atewa Forest Research Report The Biodiversity of Atewa Forest Research Report January 2019 Authors: Jeremy Lindsell1, Ransford Agyei2, Daryl Bosu2, Jan Decher3, William Hawthorne4, Cicely Marshall5, Caleb Ofori-Boateng6 & Mark-Oliver Rödel7 1 A Rocha International, David Attenborough Building, Pembroke St, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, UK 2 A Rocha Ghana, P.O. Box KN 3480, Kaneshie, Accra, Ghana 3 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum A. Koenig (ZFMK), Adenauerallee 160, D-53113 Bonn, Germany 4 Department of Plant Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3RB, UK 5 Department ofPlant Sciences, University ofCambridge,Cambridge, CB2 3EA, UK 6 CSIR-Forestry Research Institute of Ghana, Kumasi, Ghana and Herp Conservation Ghana, Ghana 7 Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, Invalidenstr. 43, 10115 Berlin, Germany Cover images: Atewa Forest tree with epiphytes by Jeremy Lindsell and Blue-moustached Bee-eater Merops mentalis by David Monticelli. Contents Summary...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Recent history of Atewa Forest................................................................................................................................... 9 Current threats -

Running Head 1 the AGE of BUTTERFLIES REVISITED

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/259184; this version posted February 2, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Running head 2 THE AGE OF BUTTERFLIES REVISITED (AND TESTED) 3 Title 4 The Trials and Tribulations of Priors and Posteriors in Bayesian Timing of 5 Divergence Analyses: the Age of Butterflies Revisited. 6 7 Authors 8 NICOLAS CHAZOT1*, NIKLAS WAHLBERG1, ANDRÉ VICTOR LUCCI FREITAS2, 9 CHARLES MITTER3, CONRAD LABANDEIRA3,4, JAE-CHEON SOHN5, RANJIT KUMAR 10 SAHOO6, NOEMY SERAPHIM7, RIENK DE JONG8, MARIA HEIKKILÄ9 11 Affiliations 12 1Department of Biology, Lunds Universitet, Sölvegatan 37, 223 62, Lund, Sweden. 13 2Departamento de Biologia Animal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de 14 Campinas (UNICAMP), Cidade Universitária Zeferino Vaz, Caixa postal 6109, 15 Barão Geraldo 13083-970, Campinas, SP, Brazil. 16 3Department of Entomology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, U.S.A. 17 4Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian 18 Institution, Washington, DC 20013, USA; Department of Entomology and BEES 19 Program, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20741; and Key Lab of Insect 20 Evolution and Environmental Change, School of Life Sciences, Capital Normal 21 University, Beijing 100048, bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/259184; this version posted February 2, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Download Document

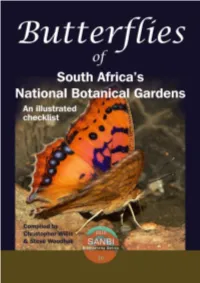

SANBI Biodiversity Series 16 Butterflies of South Africa’s National Botanical Gardens An illustrated checklist compiled by Christopher K. Willis & Steve E. Woodhall Pretoria 2010 SANBI Biodiversity Series The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) was established on 1 Sep- tember 2004 through the signing into force of the National Environmental Manage- ment: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA) No. 10 of 2004 by President Thabo Mbeki. The Act expands the mandate of the former National Botanical Institute to include responsibili- ties relating to the full diversity of South Africa’s fauna and flora, and builds on the internationally respected programmes in conservation, research, education and visitor services developed by the National Botanical Institute and its predecessors over the past century. The vision of SANBI: Biodiversity richness for all South Africans. SANBI’s mission is to champion the exploration, conservation, sustainable use, appre- ciation and enjoyment of South Africa’s exceptionally rich biodiversity for all people. SANBI Biodiversity Series publishes occasional reports on projects, technologies, work- shops, symposia and other activities initiated by or executed in partnership with SANBI. Photographs: Steve Woodhall, unless otherwise noted Technical editing: Emsie du Plessis Design & layout: Sandra Turck Cover design: Sandra Turck Cover photographs: Front: Pirate (Christopher Willis) Back, top: African Leaf Commodore (Christopher Willis) Back, centre: Dotted Blue (Steve Woodhall) Back, bottom: Green-veined Charaxes (Christopher Willis) Citing this publication WILLIS, C.K. & WOODHALL, S.E. (Compilers) 2010. Butterflies of South Africa’s National Botanical Gardens. SANBI Biodiversity Series 16. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. ISBN 978-1-919976-57-0 © Published by: South African National Biodiversity Institute. -

Butterflies in Ologbo Forest

BUTTERFLIES IN OLOGBO FOREST Dr. Oskar Brattström [email protected] Survey efforts and methodology This survey combines data from tree visits to Ologbo. Initially Robert Warren made a two day survey 8-9 June 2006 and this brief visit produced a number of interesting records. I made a preliminary visit 27-31 October 2008 to asses if the area had potential for future butterfly studies. The result from these two shorter was promising and I therefore returned 22 March – 2 April 2009 to make a more detailed study. The main survey efforts have been concentrated two the South and North-west parts of the Ologbo Forest. Butterflies were captured using hand netting (most days between 09:30-14:00) and banana/pineapple baited traps, in most cases traps were left in the field over nights and re-baited at regular intervals. Captured specimens were either identified immediately in the field or brought back for later identification. There are still a large number of specimens waiting identification. Some species were also indentified on the wings when capture was not possible. One day was spent in the plantation itself (South of the Dura Club) to get an idea of what species of butterflies are present in an area with fully matured oil palms some distance away from a semi-natural forest. In this area only hand netting and visual observation was used, as the typical canopy species which can often only be recorded using traps hardly occur in this type habitat. In general it was very easy to detect and identify butterflies in this more open type of habitat and most of the species were well known savannah butterflies. -

135 Genus Dingana Van

AFROTROPICAL BUTTERFLIES 17th edition (2018). MARK C. WILLIAMS. http://www.lepsocafrica.org/?p=publications&s=atb Genus Dingana van Son, 1955 Transvaal Museum Memoirs No. 8: 70 (1-166). Type-species: Leptoneura dingana Trimen, by original designation. The genus Dingana belongs to the Family Nymphalidae Rafinesque, 1815; Subfamily Satyrinae Boisduval, 1833; Tribe Dirini Verity, 1953. The other genera in the Tribe Dirini in the Afrotropical Region are Paralethe, Aeropetes, Tarsocera, Torynesis, Dira and Serradinga. Dingana (Widows) is an Afrotropical genus containing seven species, confined to South Africa and Swaziland. The genus was reviewed by G.A. & S.F. Henning, in 1996 (Metamorphosis 7 (4): 153-172). Diagnosis. Adult nearest to Dira Hübner, from which it differs in the absence of an areole at base of hindwing, and details of both male and female genitalia: narrow and elongate aedeagus and strongly developed juxta in male, and absence of signa in female (Henning & Henning, 1996). Characters. Antennae 39-41 jointed, club gradual, but well-defined, 14-jointed, palpi obliquely upturned, first joint rather large, almost half the length of the second, third joint elongate- ellipsoidal, one-third the length of the second. Eyes hairy. Anterior legs of both sexes strongly reduced and hidden among the hairs of thorax, tibiae only a little more than half length of femora, tarsi of male minute, fusiform, of female two-thirds the length of tibiae, four-jointed. Normal legs short and slender, tarsi with paronchyia and pulvilli present. Wing-venation. Forewing Sc not conspicuously swollen near base, but gradually tapered from base to its end, R1 and R2 from cell before upper angle, R3-R5 stalked from upper angle, upper discocellular oblique, half the length of median discocellular, the latter very little incurved, lower discocellular three times the length of median discocellular, slightly excurved, M3 from lower angle, CuA1 arises nearer to M3 than to CuA2.